Jimmie Newberry

James Lee “Jimmie” Newberry was a starting pitcher for the Birmingham Black Barons from 1942 to 1950. Most newspapers and historical sources refer to “Jimmy” as the diminutive of Newberry’s first name. However, the best evidence, which includes two autographs, signed “Jimmie Newberry,” is that he preferred to use the variant “Jimmie.”1

James Lee “Jimmie” Newberry was a starting pitcher for the Birmingham Black Barons from 1942 to 1950. Most newspapers and historical sources refer to “Jimmy” as the diminutive of Newberry’s first name. However, the best evidence, which includes two autographs, signed “Jimmie Newberry,” is that he preferred to use the variant “Jimmie.”1

Newberry was born on June 26, 1919, in Ruthven, a sawmill town in Wilcox County, Alabama.2 He was the sixth of 10 children born to Will and Lula Newberry. Two of his brothers played professionally for the Chicago American Giants in 1947: An older brother, Henry, was a pitcher, and a younger brother, Richard, was an infielder.3 Richard also played four seasons in the Northern League, where he consistently batted over .300.4 Jimmie Newberry’s nephew, James Lovejoy, credited Lula Newberry for the family’s baseball talent, recalling that she was always a good hitter at family reunions.5

Will Newberry worked as a laborer at the sawmill and Lula worked as a tenant farmer.6 By any measure, rural Wilcox County was one of the poorest counties in Alabama; only 10 years after Jimmie Newberry’s birth, the Black Belt county’s population had decreased by nearly 20 percent, from 31,080 to 24,880.7 The lack of opportunity under the sharecropping-based economy caused the mass exodus of many black families during the Depression. The Newberrys left Wilcox County sometime between 1930 and 1935 after a family member had a dispute with a local store owner who threatened to involve the Ku Klux Klan.8 The move would prove to be a good decision for the future of the family; modern Wilcox County’s population has shrunk to slightly over 11,000, and it remains the poorest county in the state, if not the entire country.9 Wilcox is one of two counties in Alabama without a federal highway, and the town of Ruthven no longer exists.10

The family settled in the north Birmingham neighborhood of Collegeville, where Will Newberry found work at the Birmingham Southern Railroad Company and later at the United States Pipe and Foundry Company.11 Jimmie Newberry dropped out of school in the sixth grade and was playing baseball by the time he was 15 years old. He got a job with the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and pitched for the L&N Stars in the Birmingham Industrial League.12

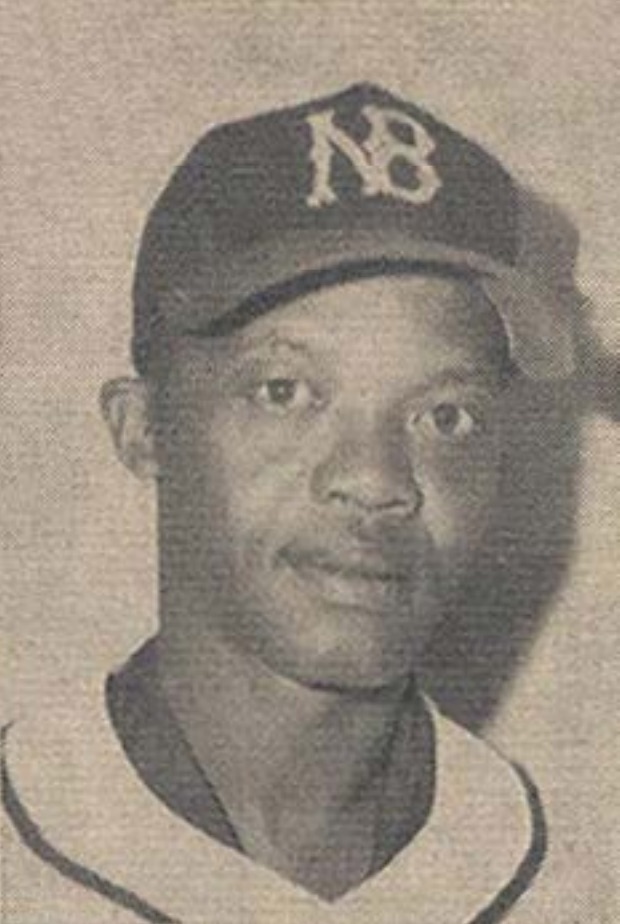

At age 23, Newberry reportedly signed with the Birmingham Black Barons late in the 1942 season, although the details of his signing are unknown.13 Not until 1943 did newspapers notice Newberry, who “won his pitching spurs in the local shop league.”14 In photographs, he had a youthful innocence, but with a mischievous grin, and sportswriters called him Schoolboy Newberry.15 Late in his career with the Black Barons, an incredulous Newberry asked a reporter, “I wonder where they get that ‘school boy’ name from? I’m no school boy. I am a man.”16 If the press thought he was an innocent schoolboy, his teammates knew him better. They called the lanky right-handed pitcher Newt.17

That he was one of the harder drinking members of the Black Barons also belied the Schoolboy nickname. Newberry was a regular patron at Bob’s Savoy on Fourth Avenue North in Birmingham, and he frequented clubs on the road whenever the team stayed in a hotel.18 Manager Piper Davis, who did not drink, kept impressionable young Willie Mays away from Newberry off the field.19 John Klima, author of Willie’s Boys, documented Newberry’s fondness for alcohol:

Kick-ya-poo juice was the hardest whiskey a man could get, moonshine even, and Newberry drank the hard stuff until it lived up to its nickname and kicked him square in the ass. He would never turn down a free drink, either. [Teammate Bill] Greason lost track of how many times he got his roommate out of trouble. …20

On the field Newberry took his job seriously and could be counted on to take the ball when it was his turn to pitch. He stood just 5-feet-7 and weighed 170 pounds, but “had a rubber arm. [He could] pitch tonight, [and] relieve tomorrow.21 Newberry “had more pitches than Satchel Paige,” according to Black Barons shortstop Artie Wilson.22 Greason fondly remembered him as one of the best-liked players on the squad, who used to entertain the other players by singing on the bus.23 In his opinion, Newberry was also one of the top pitchers on the ballclub; he had a good fastball and a devastating curve that he could throw with the same pitching motion.24 Davis, Newberry’s manager in 1948 and 1949, went even further, citing Newberry as being “one of the best pitchers playin’ in that league.”25

Wilson described Newberry’s array of pitches as including a “knuckleball, screwball, sinker, dipsy-doo – that was an overhand drop – and he had a good fastball too. [He] could make it run in, make it run out.”26 The dipsy-doo was Newberry’s out pitch. Wilson remembered, “[E]very time he’d get two strikes on a guy, I’d holler from short, ‘Time for the dipsy-doodle, Jim’ – and that was all for that batter.”27 James Lovejoy, who saw his uncle pitch at Rickwood Field, described Newberry’s curve:

He threw a curveball you would not believe. Have you ever seen the Sandy Koufax curveball? He could throw it at Second Street and it came in at home plate. … Nobody wanted to face Newt. He had a good fastball, but, buddy, that curve was mean. That was his pitch!28

Newberry quickly became one of manager Winfield Welch’s top pitchers on the Black Barons, and he posted a 3.22 earned-run average in 1944.29 Birmingham won back-to-back Negro American League pennants in 1943 and 1944 but succumbed both times to the Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series. During this period, the Black Barons had one of the most imposing pitching staffs in the league, which one newspaper called “as great a hurling corps as the league has ever seen.”30 The Birmingham World credited Welch with developing Newberry and other local players “to stardom.”31 Despite Newberry’s 3.06 earned-run average and 12-2 record, as reported contemporaneously by the Los Angeles Times, the Black Barons could manage only a frustrating second-place finish in 1945.32

Newberry also learned new tactics to use when his famed curve was not breaking. On a hot August day in Baltimore late in the 1945 campaign, the Elite Giants accused Newberry of cutting balls to increase the break in his pitches.33 Welch “denied that his pitcher was resorting to such illegal tactics.”34 However, after the umpire replaced several scuffed balls with new ones, Vernon Greene, the Giants’ business manager, presented “Welch with a total of 17 balls thrown out of the game by the umpire, which he charged showed definite signs of having been scratched by an object with sharp or rough edges.”35 Welch removed Newberry from the game. Catcher Roy Campanella later asserted, “[w]hen y’all don’t cut it, it goes up against the fences,”36 as he went 2-for-3 with a double.37 Despite the accusations of ball cutting, Newberry’s strong performance in 1945 earned him a raise the next year.38

Now 27, as Newberry entered the prime of his baseball career, he married gospel singer Willie May Thomas, a contralto with the popular Gospel Harmoneers, who were later renamed the Gospel Harmonettes.39 Their marriage did not last long, although the specific details regarding their divorce are not available. On the field, the newspapers now identified Newberry as the headliner of the Black Barons staff, and he delivered an 11-6 record in 1946, although the Black Barons missed the postseason again.40

In 1947 Newberry met with success early in the year. In a spring exhibition game at Rickwood Field, he relieved Jehosie Heard, and scattered five hits in four scoreless innings of relief in shutting down the Cleveland Buckeyes, who always struggled to hit his repertoire of pitches.41 In April Newberry struck out 11 batters to defeat the Black Barons’ archnemesis, the Homestead Grays.42 With a 5-2 record, he was selected to the West All-Star squad for the biannual East-West All-Star game in Chicago, though he did not play in the game.43 After the Black Barons finished third in the Negro American League, Newberry barnstormed with the Kansas City Royals as they battled Bob Feller’s All-Star team in the fall.44

Newberry posted the best statistical record of his career in 1948, which was arguably the Birmingham Black Barons’ greatest season. Ellis Jones of the Birmingham World had forecast a pennant for Birmingham and expected a strong performance for Newberry, writing:

Jimmie Newberry, for years the standard bearer of the Ebony Barons slabmen, has just returned from south-of-the border and will join his teammates upon their return from the Carolinas. Newberry won 5, lost 6, last year but is expected to show the form this year that ranked him as one of the game’s greatest hurlers.45

The prediction was prescient. In late May Newberry struck out 10 in a close loss to Memphis.46 By June, the newspapers were touting him as the “ace of the staff.”47 On July 31, with Pepper Bassett behind the plate, Newberry outdueled Cleveland’s Vibert Clarke – who allowed only six hits – by throwing a no-hitter to defeat the Buckeyes, 4-0, in Dayton, Ohio.48 (On the same day that the Birmingham World reported the no-hitter, Newberry grumbled that Birmingham’s fans “ride me too much.”49) The fans eventually must have appreciated him, since he led the squad in every major pitching category, finishing with a 14-5 record, 112 strikeouts in 157 innings, and a 2.18 earned-run average.50 That performance helped the Black Barons clinch a playoff spot against the Kansas City Monarchs, who they defeated to win the Negro American League pennant.

Newberry was the natural choice to start Game One of the Negro League World Series against the Homestead Grays. He pitched well, throwing a complete game and striking out six, but gave up three runs in the second inning, which was enough for the opportunistic Grays, and lost 3-2.51 For the series, Newberry had a 2.31 earned-run average in 11⅔ innings pitched, but his efforts were not enough as the Grays won the series, four games to one. 52

At the beginning of 1949, sportswriter Wendell Smith cited Newberry, now 29, as a Negro American League player who could be offered a major-league contract; however, he also noted that Newberry’s age was working against him, since he would turn 30 during the season.53 In May, as if to prove that his 1948 no-hitter was no fluke, Newberry threw another against the Buckeyes, who were now based in Louisville, Kentucky.54 Before he could replicate his success of 1948, a vicious line drive broke his pitching arm in June.55 The break was severe enough to end his season after only nine starts through which he had a 4-2 record.56 By October, Newberry had recovered and appeared in an exhibition game for the Creole All-Stars against Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars in Atlanta’s Ponce De Leon Park.57

In the following year, Newberry’s last as a Black Baron, both he and the team started fast. In late May he struck out 12 in a grueling 15-inning start for Birmingham; the Birmingham World reported that he had also registered 21 strikeouts over his previous two games.58 With Newberry recording an 8-3 record, the first-place Black Barons won 13 games in a row.59 The only thing hotter was the team’s bus, which caught fire in New York City on June 7, destroying the equipment and the players’ belongings.60 The bus fire was a fitting symbol for the end of the most competitive period for Birmingham in the Negro American League.

On June 20 the Birmingham World reported that Newberry had jumped the club during the New York City trip to join a Canadian team.61 Details emerged over the next few days that he signed with the Winnipeg Buffaloes of the Manitoba-Dakota (ManDak) Baseball League, who were raiding players from the Negro Leagues under manager Willie Wells.62 Black Barons owner Tom Hayes later claimed he had advanced Newberry his salary before he left the team, a charge Newberry’s nephew, James Lovejoy, disputes; Lovejoy maintains that Hayes was a skinflint, who refused to pay his star pitcher what he was worth.63 Winnipeg offered Newberry an enticing salary, so he agreed to pitch in Canada, where he joined former Black Barons teammates Lyman Bostock, John Britton and Johnny Cowan. Hayes was furious and, in a futile gesture, suspended his star pitcher indefinitely.64

With the New York Giants’ signing of Willie Mays announced only two weeks after Newberry left Birmingham, and Artie Wilson having already left for Oakland, the core of the Birmingham Black Barons was quickly disintegrating. By the end of the season, Piper Davis would be gone and the end of the era would be complete.

Newberry was soon dazzling batters in Canada with his wide variety of pitches.65 The ManDak league also provided a chance for him to pitch on an all-black squad in an integrated league. In Canada life was easier for black players as there were no Jim Crow laws. Newberry and his teammates discovered a more egalitarian society, which offered them real freedoms. On the mound, he pitched well; he won his first start on June 17 while striking out 11 and won both games of a doubleheader on August 24.66 He finished at 7-7 and pitched 14 complete games as the Buffaloes advanced to the ManDak championship series.67 In the series, against the Brandon Greys, Newberry won two games and saved another, as Winnipeg won the league title.68 Catcher Frazier “Slow” Robinson recalled that Newberry’s dipsy-doodle curve remained effective and “drove batters nuts.”69

In 1951 Newberry started 6-3 while pitching in 12 games for the Buffaloes.70 His time in Canada was short-lived, however. Newberry’s former manager, Winfield Welch, who was now the manager of the Chicago American Giants and a scout for Bill Veeck’s St. Louis Browns, began to follow the Buffaloes. In spite of the indefinite suspension imposed by Hayes, Welch signed Newberry to pitch for the American Giants and the pitcher returned to the United States. Marcel Hopson of the Birmingham World reported that Newberry expected to join Satchel Paige on the St. Louis Browns shortly, and happily added, “[i]t’s great to know that Newberry is back in the fold.”71 Newberry finished with a 2-1 record for Chicago, but he did not join Paige on the Browns because Veeck had other plans for him.72

During the mid-1940s Abe Saperstein had been the Black Barons’ business manager for Hayes. He liked Newberry and advanced his salary to him regularly.73 By the early 1950s, Saperstein was a minority owner of the St. Louis Browns and a scout. In February of 1952, the Associated Press reported that Saperstein requested permission from owner Bill Veeck to reach a working relationship with a Japanese professional team for player development, an idea that Veeck approved despite some hesitation.74 On April 28, 1952, the Browns announced the signing of Newberry and third baseman John Britton, who were training with the independent Thomasville Tomcats, and revealed that the pair was being loaned to the Hankyu Braves of the Japanese Pacific League. Newberry became the first black professional pitcher in Japan after World War II.75

During the mid-1940s Abe Saperstein had been the Black Barons’ business manager for Hayes. He liked Newberry and advanced his salary to him regularly.73 By the early 1950s, Saperstein was a minority owner of the St. Louis Browns and a scout. In February of 1952, the Associated Press reported that Saperstein requested permission from owner Bill Veeck to reach a working relationship with a Japanese professional team for player development, an idea that Veeck approved despite some hesitation.74 On April 28, 1952, the Browns announced the signing of Newberry and third baseman John Britton, who were training with the independent Thomasville Tomcats, and revealed that the pair was being loaned to the Hankyu Braves of the Japanese Pacific League. Newberry became the first black professional pitcher in Japan after World War II.75

Newberry soon discovered that “the Japanese players were smaller and made for a smaller strike zone. … [H]e had to work on his control and remember to keep the ball down.”76 This change made Newberry’s results for Hankyu even more impressive. He finished with a record of 11-10 and an ERA of 3.23 in 206⅓ innings pitched and made the all-star team for the fifth-place Braves.77 The switch-hitter also batted .288, which was the fifth highest average for Hankyu.78

Newberry was popular with Japanese fans, who welcomed him and Britton.79 They were so well-liked that “about 1,000 fans escorted [them] to the plane to bid [them] farewell … when [they] left for the States.”80 Despite a successful campaign in Japan, the 33-year-old Newberry decided not to play a second season in Osaka because he wanted to win a spot with the Browns.81 He was unsuccessful in that endeavor, so he returned to Canada in 1953, playing for the Carman Cardinals and posted a 5-9 record while leading the league with 30 appearances.82

From 1954 to 1956, Newberry played for six independent professional teams in nearly every corner and region of Texas. His tour of Texas began near the southeast with the Bryan Indians, where he pitched in the Class-B Big State League from April until July 19, 1954. In June Newberry suffered probably the worst pitching performance of his career, against the Tyler Tigers, in which he gave up three home runs, three doubles, and 18 hits in a 13-1 loss; his dipsy-doodle curve clearly was not breaking that day, but his defense did not help either as the Indians committed seven errors.83 Bryan’s record was 32-65 and the team was mired in seventh place on July 19, when owner Arturo Gonzalez dealt Newberry and pitcher Roland Jones to the Abilene Blue Sox in north-central Texas.84 Financial conditions forced Gonzalez to sell even more players.85 The team was losing money as fast as it was losing games, and relocated to Del Rio the following week.86 All things considered, Newberry had pitched well for Bryan and led the Indians in wins with a 9-10 record.87

Newberry’s new team, the Abilene Blue Sox, played in the Class-C West Texas-New Mexico League and was in contention for a playoff spot when it purchased his contract from Bryan. Manager Jay Haney expressed confidence in his new pitchers, saying, “You can quote me on this. I believe that these two boys are just what we needed to not only keep us in the first division, but help us to overtake Pampa for first place by the end of the season.”88 Newberry met with mixed results as he finished 2-5 for Abilene.89 He threw a three-hitter against the Lubbock Hubbers in early August but lost, 2-0.90 On August 31 he threw a five-hitter and won an important game to get the Blue Sox close to a playoff berth.91 The Blue Sox did end up making the playoffs, but they lost to the first-place Pampa Oilers in the Shaughnessy playoff format.92

In 1955 Newberry returned to the Class-B Big State League and signed with the Port Arthur Sea Hawks on the Texas Gulf Coast, where he pitched primarily as a reliever.93 In the spring he led the team with a 3-0 record and surrendered only a single unearned run in 22 innings.94 His fortunes took a downturn, and he began to struggle to get outs after the league’s hitters adjusted to his pitches. Newberry finished his stint at Port Arthur with a 6-4 record, allowing 69 earned runs for a 5.01 earned-run average while striking out 51 batters in 124 innings.95 At the end of July, Port Arthur traded him to the Big Spring Cosden Cops of the Class-C Longhorn League.96 Newberry’s former Black Barons teammate Jim Zapp was sent by the Cosden Cops to the Sea Hawks, apparently as part of the deal.97

Newberry won a game in his first appearance for Big Spring and appeared in several games, but his complete statistics for the Cosden Cops are unavailable.98 He spent less than three weeks with Big Spring before leaving West Texas for the Panhandle, after the Amarillo Gold Sox of the Class-C West Texas-New Mexico League obtained him.99 Details regarding the acquisition are also lost to history.

Newberry faced his former team, the Abilene Blue Sox, in his first appearance for Amarillo. He relieved starter Dean Higgins and recorded the third out of an inning in a wild 15-14 victory over Jay Haney’s squad.100 Ten days later, Haney got his revenge as Newberry started against Abilene and lost, 4-2, though he pitched well and allowed no hits until the fourth inning.101 Newberry finished the regular season with a 0-3 record for Amarillo; he allowed 31 runs and struck out 13 batters in just 23 innings pitched.102 The Gold Sox finished in first place in the league but lost the championship series to the third-place Pampa Oilers, four games to one.103 In the playoffs, Newberry pitched well in relief, shutting out the Pampa over 3⅔ innings in Game Three on September 17.104 He also threw a scoreless inning of relief the following day as the Gold Sox won their only game of the series.105

Newberry’s tour of Texas ended in the westernmost part of the state in 1956, when he pitched in a handful of games for the El Paso Texans of the Class-B Southwestern League in late April and early May.106 In the last news story in which his name appeared, the 37-year-old battled until the end: “Newberry replaced McNeal on the mound for the Texans and was greeted by a single by Frank Kemper, which scored Cross. A double by Flores put men on first and third, but Newberry then retired the side on infield outs.”107 Details regarding Newberry’s statistics and the circumstances of his departure from the Texans are not available.

Newberry did not play baseball professionally in 1957 and 1958. In 1959 he briefly attempted “a comeback with the Lloydminster-North Battleford Combines in the Canadian-American League, but saw action in only one game.”108

After his baseball career ended, Newberry had no second career. He traveled the country and stayed with friends, mostly former ballplayers, including Al Smith and Joe Black. He always dressed well, wearing a suit with wing-tip shoes and a hat, and he liked to go to clubs. In Chicago he stayed with his sister, Minnie Newberry Lovejoy, and her son James for many years in the South Side.109 When James Lovejoy coached Little League baseball, Newberry would sometimes help out by showing the kids how to throw the curve. Lovejoy remembered that Abe Saperstein was always generous to Newberry in the 1960s: “Abe Saperstein took care of my Uncle in Chicago. … [W]hen he needed money he would go see him, and Abe would say, ‘Newt, what are you doing?’ He said, ‘Well, I’m trying to get by today,’ and Abe Saperstein would give him money.”110 Later, when Bill Veeck bought the Chicago White Sox for the second time, he always gave Newberry tickets to games at Comiskey Park in the 1970s.111

Richard Newberry Jr., another nephew, also remembered his uncle with fondness: “He was a great guy. He came to visit us when I was a young boy. He was a bigger-than-life person. He could juggle. He could ride a bicycle backwards. And the things that he could do with a baseball were amazing.”112

On June 23, 1983, two weeks after his 64th birthday, Jimmie Newberry died in Bremen Township, Illinois, of cardiac arrest brought on by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. His death certificate appropriately identified his usual occupation as “Baseball Player.”113 He was cremated at Chicago’s Oak Woods Cemetery.

On May 25, 1987, James Lovejoy drove to Comiskey Park to see the Chicago White Sox play the Kansas City Royals. As he walked up to the ticket booth, bought a ticket to the game, and entered the ballpark, none of the White Sox employees noticed the small container that he carried under his jacket. He sat in the lower stands on the first-base side near the foul pole in right field.114 Bret Saberhagen, who had a good curveball, threw a six-hit complete game and struck out six batters as the Royals defeated the White Sox, 6-1.115 The box score did not record the most significant event that day. During the game, whenever the fans rose to cheer, Lovejoy scattered Newberry’s ashes into right field.116 Jimmie Newberry, who once had scattered hits as a pitcher in what would become America’s oldest baseball park (Rickwood Field), had his ashes scattered at what was then the oldest professional ballpark (Comiskey Park).

In 2016 the Birmingham News named the greatest athlete from each of Alabama’s 67 counties. The paper credited Jimmie Newberry as the representative of Wilcox County, Alabama.117

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to Frederick C. Bush for helping him to locate Jared Newberry, who helped him to contact Richard Newberry Jr. It was Richard Jr. who put the author in touch with James Lovejoy; the story of Jimmie Newberry’s later life could not have been told without his help. At the 2013 Rickwood Classic, the minor-league Birmingham Barons commemorated the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons team. Jimmie Newberry, smiling broadly, appeared on the promotional poster for the event. The author is proud to have been able to share copies of the poster with the Newberry family.

Notes

1 Alabama. Wilcox County. 1930 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry.com. February 12, 2017 (“Jimmie”). ancestry.com; Death Certificate for Jimmie Newberry, June 23, 1983, File No. 036274, Illinois Department of Public Records (“Jimmie”); a scorecard for the 1950 season created by the Birmingham Black Barons (“Jimmie”); and the Official Statistics compiled by the Howe News Bureau (Chicago) (“James” or “Jimmie”). The author is grateful to James Tate, who provided a copy of Jimmie Newberry’s signature with a barnstorming team led by Willie Mays; in addition, while playing for the Winnipeg Buffaloes, Newberry signed an autograph, “Jimmie Newberry, Best Wishes.”

2 Death Certificate for Jimmie Newberry, June 23, 1983, File No. 036274, Illinois Department of Public Records. Alabama. Wilcox County. 1930 U.S. Census.

3 Armand Peterson and Tom Tomashek, Town Ball, The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 290-292; Frank White, They Played for the Love of the Game: Untold Stories of Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2016, Kindle Edition), 2033; James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 581.

4 Riley, 581; Peterson and Tomashek, 290-292.

5 James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, March 1, 2017.

6 Alabama. Wilcox County. 1930 U.S. Census.

7 census.gov/population/cencounts/al190090.txt.

8 James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

9 census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/01131; Brendan Kirby, “4 Things To Know About Poverty in Wilcox County,” AL.Com, February 16, 2014.

10 Virginia O. Foscue, Place Names in Alabama (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989), 121; James Frederick Sulzby, Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1960), 259.

11 Alabama. Jefferson County. 1940 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry.com. February 14, 2017. ancestry.com; Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

12 Riley, 581; Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham (Jefferson. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 87; Larry Powell, Industrial Baseball Leagues in Alabama, October 19, 2009, encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2479.

13 Birmingham Black Barons, 1950 Scorecard; Powell, 87; Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, May 27, 1949: 7.

14 “Barons Tame Giants, 2-0,” Birmingham World, August 2, 1943: 4.

15 “Fighting Black Barons Primed for Battles With Eastern Foes,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1943; “Black Barons Showing Much Class Here,” Birmingham World, April 4, 1944: 5.

16 Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, June 6, 1050: 4.

17 Rev. Bill Greason, telephone interview with author, February 10, 2017; Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

18 Rev. Bill Greason, interview.

19 Riley, 581 John Klima, Willie’s Boys (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 108.

20 Klima, 109.

21 Stan Federman, “I Loved the Game,” Oregonian (Portland), August 8, 1991.

22 robneyer.com/baseball-books/neyer-james-guide-to-pitchers/pitchers-l-to-r/.

23 Rev. Bill Greason, telephone interview with author, February 24, 2017.

24 Rev. Bill Greason, February 10 interview.

25 Brent Kelly, Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period 1924-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 131.

26 robneyer.com/baseball-books/neyer-james-guide-to-pitchers/pitchers-l-to-r/.

27 Federman, 3.

28 Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

29 Official Negro American League Statistics for 1944, compiled by the Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

30 “Cubans Play Barons Sunday,” Chicago Defender, March 31, 1945: 7.

31 “Picks Black Barons to Win Championship Again,” Birmingham World, April 25, 1945: 6; Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, July 3, 1945: 3.

32 Official Negro American League Statistics for 1945, compiled by the Howe News Bureau (Chicago); “Royals, Barons Meet Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, October 31, 1945: A9.

33 “Elites, Charging Illegal Pitching, Beat Barons, 6-2,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 18, 1945: 26.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Frazier Robinson, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 161.

37 “Elites, Charging Illegal Pitching, Beat Barons, 6-2.”

38 Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, January 22, 1946: 5.

39 Rev. Bill Greason, February 10 interview; James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, March 1, 2017;

Vladimir Bogdanov, Chris Woodstra, and Stephen T. Erlewine, editors, All Music Guide to the Blues (San Franciso: Backbeat Books, third edition, 2003), 121.

40 Riley, 581.

41 “Black Barons Defeat Cleveland Buckeyes,” Atlanta Daily World, March 25, 1947: 5.

42 “Wild Hurling of Grays Enable Barons to Win,” Norfolk (Virginia) Journal and Guide, April 26, 1947: 14.

43 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 295.

44 “Royals, All-Stars in Doubleheader Sunday,” Los Angeles Sentinel, October 16, 1947: 23; “Bob Feller’s 9 in 2-1 Win Over Royals,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, October 25, 1947: 14.

45 Ellis Jones, “Black Barons Eye ’48 Championship; Leave City for Exhibition Games,” Birmingham World, April 6, 1948: 5.

46 “Cleveland Rips Chi Twice; Memphis, Barons Split,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 5, 1948: 15.

47 “Indianapolis Clowns to Meet B’ham Black Barons Today,” Atlanta Daily World, June 24, 1948: 5.

48 Marion E. Jackson, “Sports of the World,” Atlanta Daily World, August 3, 1948: 5; “Cleveland Buckeyes Defeated by Barons,” Atlanta Daily World, August 4, 1948: 5; “Hurls No-Hitter,” Birmingham World, August 6, 1948: 6.

49 Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, August 6, 1948: 6.

50 Official Negro American League Statistics for 1948, compiled by the Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

51 Larry Lester and Dick Clark, “Day by Days for Pitchers – World Series,” Negro League Researchers and Authors Group, 2004, 4. “Homestead Grays Defeat Black Barons 3 to 2,” Birmingham World, September 28, 1948: 4.

52 Lester and Clark, 4.

53 “Few, If Any, Colored Stars Ready to Join Majors, Says Negro Scribe,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1949: 13.

54 Emory O. Jackson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, May 10, 1949: 2; “Cubans to Play Black Barons,” New York Times, May 42, 1949: 36.

55 “New York Cubans Lose Twice to First Place Black Barons,” Atlanta Daily World, June 15, 1949; Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, March 1, 2017.

56 “Black Barons Edge New York Cubans,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 18, 1949; Official Negro American League Statistics for 1949, compiled by the Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

57 “Robinson’s All-Stars to Play Here Sunday,” Atlanta Daily World, October 12, 1949: 5; “Robinson, Campanella, Newcombe, Doby in ‘All-Star Dream Game’ at Poncey Park,” Atlanta Daily World, October 16, 1949: 7.

58 “Barons, Memphis Play to 4-4 Tie,” Birmingham World, June 2, 1950: 2.

59 “Mays’ Big Bat Sparks Barons’ Win Streak,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 24, 1950; photo inset, Birmingham World, June 16, 1950; Black Barons Pitchers Record, Birmingham World, July 18, 1950: 4.

60 Marcel Hopson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, June 23, 1950: 6.

61 Marcel Hopson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, June 20, 1950: 3.

62 Robinson, 164-165.

63 Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, March 1, 2017.

64 Marcel Hopson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, June 27, 1950: 6.

65 Marcel Hopson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, June 30, 1950, 7.

66 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 121.

67 Robinson, 170; Swanton and Mah, 121.

68 Swanton and Mah, 121.

69 Robinson, 170.

70 Swanton and Mah, 121.

71 Marcel Hopson, “Hits and Bits,” Birmingham World, August 3, 1951: 6.

72 Statistics published in the Baltimore Afro-American, September 4, 1951: 16.

73 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jimmy_Newberry.

74 Ibid.

75 Gary Ashwill, “Early Black Ballplayers in Japan,” agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2013/02/early-black-ballplayers-in-japan.html, accessed March 21, 2017.

76 Robinson, 171.

77 baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=5b45c99a; and http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jimmy_Newberry.

78 baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=f7b7734f.

79 Robert K. Fitts, Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 119; Robinson, 171.

80 Fay Young, “Fay Says,” Chicago Defender, February 14, 1953: 22.

81 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1952: 38.

82 Swanton and Mah, 121.

83 “Indians Lose to Tyler in First Game of Series,” Bryan (Texas) Eagle, June 7, 1954: 7.

84 “Baseball Standings,” Bryan Eagle, July 20, 1954: 8; “Austin Widens Lead With 5 to 3 Win Over Indians,” Bryan Eagle, July 20, 1954: 8.

85 Dave Campbell, “On Second Thought,” Waco News-Tribune, July 24, 1954” 12.

86 “Bryan Indians May Be Moved,” Bryan Eagle, July 11, 1954, 6; “Last Year of Pro Ball in Bryan,” Bryan Eagle, July 11, 1954, 6; “Indians Granted Permission to Move Team to Del Rio,” Bryan Eagle, July 25, 1954: 5.

87 “Redskins Records,” Bryan Eagle, July 18, 1954: 6.

88 “Haney Confident New Hurlers will Click,” Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News, July 23, 1954: 10-A.

89 “WT-NM AVERAGES,” Pampa (Texas) Daily News, September 12, 1954: 7.

90 “Alonso After 19th Against Hubbers,” Abilene Reporter-News, August 3, 1954: 6-A.

91 “Blue Sox Playoff Berth,” Pampa Daily News, September 1, 1954: 7.

92 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/West_Texas-New_Mexico_League.

93 “Sea Hawks Romp Past Texas City Texans 10 to 1,” Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), April 21, 1955: 9; “Clippers Risk Lead Against Texas City,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, April 27, 1955: 6-B.

94 “Ed Charles Leads Big State Hitters,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, May 1, 1955: 13-B; “Big State League,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1955: 35.

95 Individual Pitching Statistics, Corpus Christi Caller-Times, August 7, 1955: 25.

96 Jack Holden, “Sports Spotlight,” Abilene Reporter-News, July 31, 1955: 2-D.

97 “Hawks Capture Pair, Leave BSL Cellar,” Waco News, July 29, 1955: 13.

98 “Holden, 2-D; Odessa Takes 3-1 Win Over Cops to Break 12-Game Losing Skein,” Odessa American, August 3, 1955, 8; Dick Clark and Larry Lester, Records of the Negro League Players (Cleveland, Ohio: SABR, 1994), 326-327.

99 “B-Sox Drop 15-14 Tilt,” Abilene Reporter News, August 15, 1955: 2A.

100 Ibid.

101 Jack Holden, “5,000 Expected to See Santa Face Pampa at 8,” Abilene Reporter-News, August 25, 1955: 2-B.

102 “WT-NM AVERAGES,” Abilene Reporter-News, September 11, 1955: 4-D.

103 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/West_Texas-New_Mexico_League.

104 Buck Francis, “Venable Goes Route; Fortin Pounds Pair of Homers,” Pampa Daily News, September 18, 1955.

105 “Sox Edge Pampa in Playoff, 6-5,” Albuquerque Journal, September 19, 1955: 15.

106 Clark and Lester, 326-327.

107 “Oilers Clip Texans, 7 to 3, Saturday,” Pampa Daily News, May 6, 1956: 11.

108 Swanton and Mah, 121.

109 James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

110 Ibid.

111 Ibid.

112 Richard Newberry Jr., telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

113 Death Certificate for Jimmie Newberry, June 23, 1983, File No. 036274, Illinois Department of Public Records

114 James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

115 Mike Kiley, “Sox Find Home Unsweet Again, 6-Hitter Gives Saberhagen 8th Victory,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1987: C1.

116 James Lovejoy, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2017.

117 al.com/sports/index.ssf/2016/12/whos_the_no_1_athlete_from_eac.html.

Full Name

James Lee Newberry

Born

June 26, 1919 at Ruthven, AL (US)

Died

June 23, 1983 at Bremen Twp, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.