Rickwood Field (Birmingham)

This article was written by Clarence Watkins

The history of Rickwood Field is a story worth telling and retelling. Its origins are compelling as is the story of its evolution throughout its 77-year existence as a functional minor-league baseball park. Perhaps of greater interest is the story of how it has survived the past 23 years as an obsolete old ballpark. Rickwood Field today stands as a relic from the past, a historical structure that has become a living museum and a symbol for all the other bygone minor-league baseball parks that were unable to survive the ravages of time.

To completely appreciate the story of Rickwood Field, it is important to understand the beginnings of the city of Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham was not a typical Southern city, being founded neither on the bluffs of a great river nor at the mouth of one. Birmingham came into existence after the Civil War when two railroad lines crossed in an area where there were rich deposits of coal and iron ore. It is a city of the New South, a term used by Atlanta journalist Henry Grady to describe Southern cities as an untapped resource to build new industries. In 1885 Grady was instrumental in forming the first professional baseball league in the South, the Southern League, to entice Northern industrialists. Southern cities had theaters, libraries, schools, and now baseball to entertain a new class of industrial workers.1

In 1877 Joseph Harvey Woodward came to Birmingham from West Virginia to take advantage of the coal and iron resources and to build an iron furnace much like the one his family operated. Joseph was also preparing his son Rick to follow in his footsteps. Rick had attended Sewanee College and then was sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to finish his education. For Rick, being a catcher on the Sewanee baseball team was far more important than math and science. While attending MIT, he got a taste of the professional game in Boston. By the time he returned home, Birmingham was a member of the new Southern Association Baseball League that had been formed in 1901. While learning the family business, Rick enjoyed managing the company baseball team, which was part of an industrial league that provided entertainment and exercise for employees. In 1909 Woodward Iron played for the league championship. During the game several players approached Rick with demands for better pay and benefits, threatening to lose the game if they were not met. He did not give in to their demands and Woodward Iron lost the championship. Rick was finished with industrial league baseball, but within a few months he negotiated the purchase of the local minor-league team, the Barons, and made plans to build a new ballpark.

In April 1909 Rick traveled to Philadelphia to see the opening of Shibe Park, one of only five concrete and steel baseball stadiums in the major leagues. He had begun to plan his new ballpark even before he had purchased the Barons and intended it to reflect the latest technology in stadium construction. He sought advice from major-league owners Connie Mack and Barney Dreyfuss, and Mack even came to Birmingham to assist Rick in laying out his new park. The initial budget was for $25,000, but it soon grew to $75,000.2 Construction began in the spring of 1910 with a completion date set for August 18.

On the morning of August 18, workers were still completing the last-minute details to finish the ballpark. The game that was to be played there that day was more than just a ballgame; it was the social event of the year for Birmingham. City workers were given the afternoon off as were most downtown retail workers so that they could attend the game. Mayor Jimmy Jones and any other politician who wanted to be seen attended the game. Rick Woodward’s father even came to see what all the “nonsense” was about. Apparently Mr. Woodward was pleased with his son’s accomplishments because he paid off all the outstanding debt from the construction.3 By 2:30 P.M. streetcars were delivering fans to the park for the 3:30 pregame ceremony that would precede the 4:00 game. The stands and bleachers had a capacity of 5,000 but the crowd — accurately counted by the turnstiles — swelled to over 10,000. Fans lined the outfield wall from the third-base line to the right-field corner, and a new Southern League attendance record was set.

As the pregame ceremonies began, Rick Woodward appeared on the field in a full player’s uniform to throw out the actual first pitch of the game. Shortly before the game began, the Barons’ star pitcher, Harry Coveleski and outfielder Bob Messenger almost came to blows in front of the Barons dugout. The fans loved it. Coveleski was in rare form and between innings he performed pugilistic antics for the crowd. The game itself almost seemed anticlimactic; it was a low-scoring affair, not uncommon at a time when the bunt was considered a big weapon of the offense. Trailing by a run in the ninth inning, the Barons use three bunts, a hit batsman, and a fielder’s choice to win the game, 3-2. For several days the newspapers sang the praises of Rickwood Field. Even the name Rickwood was the idea of local fans, who had participated in a contest to name the new venue. The newspapers spoke of Rickwood adding to the aura of the “Magic City.” It would be 15 years before the other Southern League teams built ballparks comparable to Rickwood. No one could have imagined that Rickwood would still be standing more than a hundred years later.

For Rickwood Field and the Barons, two league championships came quickly in 1912 and 1914; however, after that, mediocrity set in. By the mid-1920s, sports in general began experiencing a golden age as Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, and Bobby Jones dominated the front pages of newspapers. Woodward Iron was booming alongside the rest of the national economy, and Rick Woodward was ready to spend whatever it took to bring the Barons back to the top. Longtime manager Carlton Molesworth was fired and several different managers took the Barons’ reins before a proven winner, Johnny Dobbs, was hired in 1926.

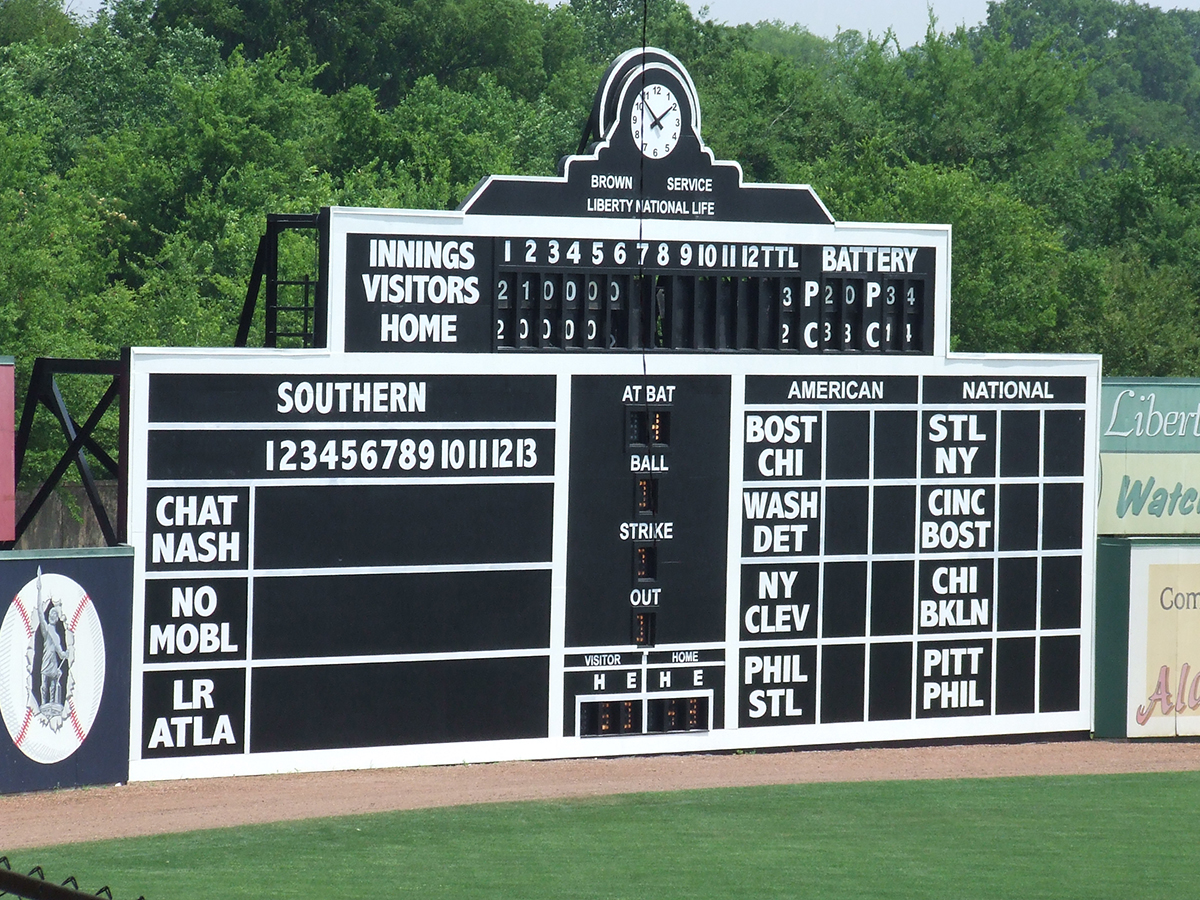

The ballpark was now over 15 years old and it, too, needed a makeover. During the winter of 1927-28, Rickwood Field received a major renovation that cost over $125,000, almost double the cost of the original park. The primary improvements included three iconic additions that remain the signature features of the park: A new scoreboard was added in left field, the bleachers were covered down the right-field line with a section of seats that wrapped around the foul line, and a new mission-style front entrance completed the park. From 1928 through 1931, Rick Woodward regularly purchased the contracts of proven major-league players to fill the needs of his team, and the Barons won three league championships.

After that period of success, the impact of the Great Depression hit the iron industry and minor-league baseball, and Woodward’s major concern was keeping his iron works from going under. Toward the end of the Depression, employees of Woodward Iron were paid in company scrip which was good only at the company store.4 By 1938 Woodward was ready to sell the team and his personal creation, Rickwood Field. Ed Norton of Birmingham bought the team, but he sold it to the Cincinnati Reds two years later, and the Barons became part of their minor-league farm system. In 1941 Cincinnati made one major change to Rickwood when they installed a new, wooden outfield wall that was located well inside the old, concrete outer wall. The hope was that more home runs would excite fans and increase attendance.

As a Reds affiliate, the Barons roster now included future major leaguers like an immature Joe Nuxhall, who was sent to Birmingham after his major-league debut in 1943. Nuxhall had let the fanfare of his short time in the majors go to his head, and it would take him six years to make it back to Cincinnati. The Reds ownership decided to sell the Barons and Rickwood Field back to another Birmingham man in 1946. Gus Jebeles, a restaurant owner, bought the team and intended to bring it back to the Barons of the golden age that he remembered from his days as a boy growing up in Birmingham.

In July 1943 the Barons had founded their team’s Hall of Fame and 40 players from the past had been part of its inaugural class. Large photographs of each player were hung in the concourse. For each year after, two players would be enshrined.

In his daily column, the Birmingham News’ Zipp Newman listed several firsts for the Barons and Rickwood Field. Along with the team Hall of Fame, Rickwood was the first park to install ceiling fans and to the outfield walls free of advertising, while the Barons were the first team to have players wear numbers on the backs of their jerseys.5

In the mid- to late 1940s the Birmingham Black Barons regularly ran ads in Barons scorecards. The one-third-page ads stated, “When the Barons are away, See the Black Barons play.” A list of future Black Barons games was included at the bottom. The ads speak at least to an amicable business relationship between the two teams, and no such ads appeared in the programs of the teams in other Southern League cities.

For Rickwood Field, Birmingham baseball in 1948 was truly a magical year. The servicemen had returned from the war, and baseball was experiencing a golden age throughout the United States. Even though the Barons finished in third place, they still posted an all-time attendance record. The third-place finish was enough to get in the playoffs, and the team got hot and rode their energized play all the way to the Southern League championship. Meanwhile, the Black Barons, managed by Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, won the Negro American League pennant over the Kansas City Monarchs and played the Homestead Grays in the last Negro League World Series. Three of the World Series’ five games were played at Rickwood Field. But soon both the Barons and Black Barons experienced steady declines, albeit for different reasons.

The Black Barons, like all other Negro League teams, eventually folded after the integration of Organized Baseball had robbed the leagues of their best talent and the majority of their fans. The fate of the minor-league Barons was also tied to race issues. After 1961 the Southern Association had lost three teams, and plans by Mayor Jimmy Jones of Birmingham to enforce the city ordinance that prohibited whites and blacks from playing sports together left owner Albert Belcher no other choice but to disband the team. Birmingham and Rickwood Field endured two years without any baseball. In 1964 the South Atlantic League was reorganized into the new Southern League and baseball returned to Rickwood Field. Whites and blacks played on the same team for the first time, and reporters from the North came to Rickwood to witness Birmingham’s first integrated game. The crowd acted respectfully and simply enjoyed having baseball back, thus turning the game into a non-event for the press.6

The Barons played again in 1965, but new owner Charlie Finley moved the team to Mobile, Alabama, for the 1966 season. The team returned to Birmingham in 1967, but was now called the Birmingham A’s. Although baseball was back in Birmingham, Rickwood Field was on the decline. The wooden outfield walls were replaced by a chain-link fence and the iconic left-field scoreboard was taken down. Attendance also declined, finally reaching a low of 25,000 by the end of 1975. In 1976 Finley moved the team to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and this time it took five years for professional baseball to return to Birmingham.

In 1978 Rickwood Field became the home of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s baseball team. The new team was coached by legendary major-league manager Harry “The Hat” Walker. During this time, most of the lower-level wooden seats were removed, and fans now sat on the concrete risers. A new addition to the park was a metal batting building that was constructed down the left-field side. Other than those two changes, very little was being done to keep the old park in shape. However, a small group of Birmingham baseball fans wanted to see professional baseball back at Rickwood.

Dr. Jack Levin led a group that planned to purchase the struggling Montgomery Rebels team. An experienced person was needed to manage such a difficult undertaking, and many locals did not believe that the task could be accomplished. In 1980 John Forney, Alabama’s football announcer, went to Memphis to interview Art Clarkson, the general manager of the Memphis Chicks who had done an outstanding job of reviving minor-league baseball in Memphis. Forney asked him to visit Birmingham and Rickwood Field to see if he would be interested in revitalizing baseball in another Southern city. When Clarkson came to Rickwood Field, he had to climb over the eight-foot chain-link fence to get into the park.7 He saw that a lot of work needed to be done, but he also imagined the site as a living baseball museum. Clarkson decided that it was a challenge he could not turn down, and he struck a deal that brought back the Birmingham Barons in 1981. Many observers thought the rundown neighborhood around Rickwood would keep large numbers of fans away, but Clarkson showed them they would come. The Barons were a success in every way and won Southern League championships in 1983 and 1987.

After several years, Clarkson realized that there were limits to how far he could take the Barons at Rickwood Field. Once again the old ballpark faced the possibility of being deserted. Clarkson examined proposals from several Birmingham-area cities and decided to move the team to Hoover, Alabama, which planned to have a new ballpark ready for the 1988 season. The franchise’s relocation appeared to spell the end of professional baseball at Rickwood Field. The City of Birmingham took over the ownership of Rickwood Field and offices for the city schools’ athletic department were moved there; it was also decided that high-school baseball games between city schools would be played at Rickwood. During the summer, city school buses were parked inside the fenced-in area down the left-field line while old, city-owned cars could be seen parked in the lots around the park. It was a sad situation for the former palace of Southern baseball. The only ray of hope was that the park was still intact and, therefore, might someday be resurrected.

In 1992 five local men — Tom Crosby, Terry Slaughter, Coke Matthews, Alan Farr, and Bill Cather — who had attended games at Rickwood Field in their youths formed an organization to save the venerable ballpark.8 By now, Rickwood had fallen into disrepair, and improvements made in the 1980s to make it usable for minor-league baseball had aged to make the park look even worse. The new organization, named The Friends of Rickwood, had a monumental task ahead of it, and something was needed to jump-start the renovation project.

In 1993 filmmaker Ron Shelton came to Birmingham to scout out a site where he could film the baseball scenes for his new movie about the life of Ty Cobb, and he chose Rickwood Field. The repairs and improvements the film crew made to the venue brought the ballpark back to life. The publicity from the film brought together others interested in seeing the ballpark saved, with the idea of completely restoring Rickwood. Soon after the movie Cobb was completed, HBO came to Rickwood Field to film a movie about Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Jackie Robinson that was titled Soul of the Game. ESPN followed suit and came to the ballpark to film commercials. The destruction of old Comiskey Park in Chicago made Rickwood Field the oldest professional baseball park in the nation, and it was now the place to be. Baseball groups soon began to rent the park for games.

In 1996 the first annual Rickwood Classic was played at the ballpark. The Birmingham Barons returned to play one game a year, and each Classic had a theme for which the teams wore period uniforms. Retired Barons players were invited back to be honored, and fans were encouraged to wear vintage clothes to complete the time-travel experience. For fans, one of the highlights of the day is to be able to go out onto the field after the game and stand on the mound where Dizzy Dean stood, or patrol the outfield where a 17-year-old Willie Mays played. The ballpark has indeed become a living museum.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Author’s note

On April 8, 2017, after an inspection by city engineers had revealed structural issues that made the park unsafe, the city of Birmingham announced that Rickwood Field would be closed to the public while repairs are made to the facility. Unfortunately, the temporary shutdown of America’s oldest ballpark occurred less than six weeks prior to the annual Rickwood Classic; the May 31, 2017 game was moved to Regions Field, the regular home of the Double-A Birmingham Barons. The Friends of Rickwood organization expends considerable time and effort in preparing for the annual event, and attending the Rickwood Classic is on many baseball fans’ bucket lists. After the initial shock of having to move the 2017 Classic wore off, it became clear that the repairs were a positive development since they were necessary to make the stands safe for fans and to ensure that Rickwood Field will endure. Once the repairs have been completed, there will be a renewed appreciation for the park. For the Friends of Rickwood and fans alike, the 2018 Classic will be like a reunion with a long-lost friend, a reunion that will continue to take place for generations to come.

Photo credits

Courtesy of Friends of Rickwood.

Notes

1 Timothy Whitt, Bases Loaded With History (Birmingham: A.H. Cather Publishing, 1995), 13.

2 Allen Barra, Rickwood Field, A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), 33.

3 Zipp Newman and Frank McGowan, The House of Barons (Birmingham: Cathers Brothers Publishing Co., 1950), 39-40.

4 Author interview with Allan Harvey Woodward III, grandson of Rickwood Field builder, A.H. Woodward, September 2016.

5 Zipp Newman, “Dusting ‘Em Off,” Birmingham News, July 13, 1943.

6 Author interview with Bob Scranton, traveling secretary for the Birmingham Barons in the 1950s and former part-owner of the Barons 1980s, several interviews from 1999 to 2008.

7 Author interview with Art Clarkson, former general manager and owner of the Birmingham Barons, November 11, 2016.

8 Author interviews with Tom Crosby, Allan Farr, and Bill Cather, board members of the Friends of Rickwood, October 28, 2016.