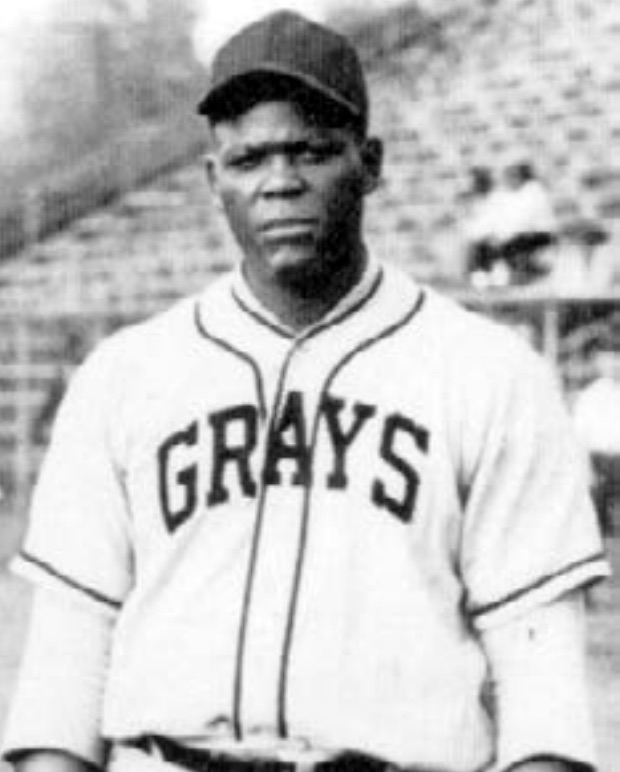

Tom Parker

Tom Parker, who also answered to the sobriquets of “Big Train” and “Country,” enjoyed a long and successful career in professional baseball. He was a pitcher and outfielder not only on the 1948 Homestead Grays, the final Negro League World Series champion, but also for an array of teams both before and after that championship season. Parker’s complete life, however, both in and beyond baseball remains untold. The whole story may never be known and, if it were not for his professional excellence at the game, his tale might already have slipped away into the anonymous shadows of the past. The Tom Parker story is one of many case studies in the challenges attached to actively remembering history, and these challenges continue to confront every Negro Leagues researcher.1

Tom Parker, who also answered to the sobriquets of “Big Train” and “Country,” enjoyed a long and successful career in professional baseball. He was a pitcher and outfielder not only on the 1948 Homestead Grays, the final Negro League World Series champion, but also for an array of teams both before and after that championship season. Parker’s complete life, however, both in and beyond baseball remains untold. The whole story may never be known and, if it were not for his professional excellence at the game, his tale might already have slipped away into the anonymous shadows of the past. The Tom Parker story is one of many case studies in the challenges attached to actively remembering history, and these challenges continue to confront every Negro Leagues researcher.1

It is likely that Parker came from Louisiana since all available sources agree that he hailed from the Alexandria area. There are, however, variant listings for his birth year; which can only be narrowed down to the time span between 1910 and 1915. Baseball-Reference.com unequivocally states that he was born on February 12, 1912, in Alexandria.2 James Riley, in his sweeping biographical survey of the Negro leagues, avers that Parker was born “about 1911,”3 and the archives contained in the Ancestry.com website list two Negro men, both named Tom Parker, who were both from Alexandria, Louisiana, and were born in 1911 and 1912 respectively.4 The Seamheads.com website simply lists Parker’s birth year as 1912.5 Neither searches of federal cemeteries in Louisiana and surrounding states6 nor the digitized version of the 1920 US Census shed light on Big Train Parker’s birth date; several Tom Parkers fall within those rough parameters.

Parker’s life in professional baseball may have begun as early as 1929 or as late as 1931. The Negro Leagues Book7 and Robert Peterson8 both state that Parker played for the Memphis Red Sox in 1929, but neither Seamheads.com nor Baseball-Reference.com corroborates that assertion. A review of an array of old issues of the Afro-American, as well as available Memphis newspaper archives, does not produce any reference to Parker playing baseball there in 1929, but such omissions provide no authoritative evidence either. It can be stated with certainty, however, that the 1931 season is the first in Parker’s baseball career that can be verified.

According to most sources, including numerous newspaper clippings, Parker was a young pitcher and utility player on the 1931 Indianapolis ABCs. As is the case in so many instances in Parker’s life and career, the various biographies diverge. Riley notes that Parker played for the Monroe Monarchs after leaving Indianapolis. The idea that he played for Monroe is interesting; the team, which existed until 1935, actually joined the Negro Southern League for the 1932 season. The Monarchs went 26-22 that year and barnstormed throughout the region, but there is no other corroboration that Parker played for the team.9 While it would be logical that a Louisiana native would play for a Louisiana team, not even historian John Holway lists Parker as a member of the team.10

In 1934 Parker definitely played for the independent New Orleans Crescent Stars. S. Derby Gisclair, via his outstanding website about baseball in Louisiana,11 found a few extant reports of Parker’s achievements, including an early-season account of a game against a Houston team in which the “heavy hitters of the Stars connected in all pinches with ‘Big Train’ Parker and Wright coming through with home runs with men on base.”12 There exists also an October addendum in which “ ‘Big Train’ Parker and Wright both poled out homers during the opener.”13 While these accounts suggest that Parker played for New Orleans for the entire year, it is also possible that he played games for the Nashville Elite Giants during the same year.14 This would have been several years before the team relocated to Baltimore, when Nashville was a full member of the second iteration of the Negro National League. His play there is not well documented but – it must again be noted – the mere absence of information does not mean that Parker did not suit up for the squad.

For a brief period of a few years, beginning in 1935, there is widespread agreement on Parker’s baseball story. Clearly talented enough to grab the attention of the major black leagues, Parker played for the Homestead Grays until 1939. He actively contributed to a 1937 World Series win by a “combined squad of Grays and Eagles” over a “team of Monarchs and American Giants.”15 Holway notes that “Tom ‘Country’ Parker of the Grays (in game two) won his own game with a two-run pinch single off Sug Cornelius. Final score: 10-7. There are no other details of the game.”16 Seamheads.com credits Parker with an 11-14 pitching record during his tenure with Homestead, a mark that he complemented with a .321 batting average as an outfielder and occasional shortstop.17

Several sources state that Parker joined the Toledo Crawfords for a time in 1939; however, in this instance, there is a lack of corroborative evidence once more. The 1940 season remains a mystery, with no source offering any reference to active participation in baseball, but by June 1941 Parker was again playing with the New Orleans Stars.18 One newspaper account noted, “In the second game Tom ‘Big Train’ Parker, recent Star recruit, blanked the Cats (sic) with three hits and added to the Floridians’ misery by hitting a home run with the bases loaded in the second inning.”19

A June 1941 article in the New Orleans Times-Picayune may shed some light on the winding path of Parker’s life, including his whereabouts in 1940. The newspaper reported that “The addition of Tom ‘Big Train’ Parker, formerly of the New York Black Yankees, to the Star lineup has greatly increased their offensive strength. Parker, with his timely hitting, has won four out of the last nine games.”20 The date of the article and the use of the word “formerly” indicate that Parker had played most recently for New York, perhaps in either 1940 or 1941, or both; this corroborates Riley’s account that Parker played for New York in both 1941 and in 1942. In a major media market like New York, it is improbable, but certainly not impossible, that there was no mention of Parker. The Times-Picayune article does validate that New York portion of Parker’s itinerant baseball journey, though.

In 1943 Parker played for the independent St. Louis-Harrisburg Stars, arriving as the final piece of a Negro National League controversy. The Afro-American shed light on how Parker came to join the Stars:

“Taking a firm stand against the St. Louis-Harrisburg Stars, the only club which has failed to comply with it recent ruling on the transfer of players, the Negro National League, Friday, ordered immediate return of two players from the Stars to the New York Black Yankees. … The players, Harry Williams, shortstop and manager, and Jim Starks, first-baseman, were ruled the property of the Black Yankees. George Mitchell, business manager of the St. Louis club, told the NNL that the players declined to leave the club because they had no desire to play with the Yankees. Under the new ruling, the players must report to the Yankees this week, with the New York club pledged to pay them the same salary the St. Louis club has been paying them. A third St. Louis-Harrisburg Stars player, Tom Parker, pitcher and outfielder, was ruled the property of the St. Louis club.”21

After a half-season of barnstorming, Parker enlisted in the US Army. According to the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, Parker’s sole year of service was 1944; he is listed as having been a member of the New York Cubans prior to his enlistment.22 After his brief tour of duty in the Army, Parker returned to the Birmingham Black Barons for the 1945 season. In Birmingham as an outfielder, he was credited with a .286 batting average, but that did not include his performance in barnstorming games throughout the South.

Parker moved to another new environment in 1946, when he joined up with the Boston Blues of the short-lived United States League as player-manager. The USL was the brainchild of former Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee, who solicited Branch Rickey’s involvement to lend greater credibility to the endeavor; however, the league folded in 1946 after less than two full seasons. At the time of the circuit’s demise, Parker had the Boston squad in first place.

Forced to relocate yet again due to the failure of the USL, Parker spent 1947 with the Detroit Senators before signing with the Washington Homestead Grays for the 1948 campaign. The Baltimore Afro-American reported, “Tom Parker, former Black Yankee and Cuban outfielder, joined the Grays Sunday. Parker is the exchange player in the Jerry Benjamin deal, in which the Cubans acquired the former Grays centerfielder.”23 Parker debuted for the Grays in the season opener, a night game against the Baltimore Elite Giants at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, and went 1-for 4. He was overshadowed by Luke Easter, who debuted with the Grays by going 3-for-3 with a home run and a double while driving in four runs and scoring twice. Parker was credited with a 7-4 pitching record that year; he also spent some time in the outfield, but he batted only .235 for the season.

The next year, with the Negro Leagues beginning to lose their collective momentum subsequent to Jackie Robinson’s major-league debut in 1947 and with age likely beginning to affect his play, Parker joined the Farnham (Quebec) Pirates of the independent Provincial League. While at Farnham, he played against teams like the Drummondville Cubs, the Granby Red Sox, the Sherbrooke Athletics, the St. Hyacinthe Saints, and the St. Jean Braves; however, after one year, Parker hit the road once more.

He remained in Canada, though, and played the 1951-1953 seasons in the Manitoba-Dakota (ManDak) League, a minor-league-level organization that embraced racial integration on the field. Each ManDak team could keep three non-Canadian players on the roster, and the average player could expect to earn between $300 and $1,000 per month.24 In 1951, with the Elmwood Giants, Parker posted a 5-2 pitching record against competition that included aging stars like Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Willie Wells, and Leon Day, and he batted .429 in 19 games. Parker’s numbers dropped off in 1952 as he managed a 5-3 record but hit only .269 for the Winnipeg Giants. During his final year in the circuit, with the Brandon Greys, he posted a 6-4 record and registered a .286 batting average in 20 games.25

According to Riley, the 6-foot-1, 230-pound Parker “was a big, robust fastball pitcher with a good curve; he also threw a slider, knuckler, and a change-up with a modicum of success and had a fair drop with average control of his pitches.”26 He also was considered to be a “true gentleman throughout his twenty-one seasons in the Negro Leagues.”27 In spite of exhaustive research efforts by numerous individuals, little else is known about Parker to date. The many unanswered questions about his life may never be satisfactorily answered since Parker and many of his Negro League contemporaries exist now only in snippets of history that have been preserved in newspaper archives. Although such news articles comprise more of a legacy than many people of earlier times enjoy, they are few and they expose a gap in the history of the game. It is unfortunate that Parker’s life was not well documented as he was obviously a much-traveled man who likely had many stories to tell about the people he had met and places he had seen.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 The list of scholars interviewed for this essay, all of whom were incredibly helpful but similarly frustrated by an absence of evidence, includes author-historians Jay-Dell Mah and Barry Swanton, Craig Britcher of Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center, Professor Rob Ruck at the University of Pittsburgh, website curator S. Derby Gisclair, the staff of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, and the staff of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York,

2 See baseball-reference.com/register/player.cgi?id=parker002tom.

3 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2002), 603.

4interactive.ancestry.com/6061/4300990_00919?pid=83859242&backurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ancestry.com%2f%2fcgi-bin%2fsse.dll%3fdb%3d1920usfedcen%26indiv%3dtry%26h%3d83859242&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true.

5seamheads.com.

6interment.net/data/us/la/rapides/alexnat/index_npf.htm, and findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=136961025&ref=acom.

7 Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds., The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994), 213.

8 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 370.

9 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 292.

10 Ibid.

11 neworleansbaseball.com/articles/html.

12 “Crescent Stars Batter Houston Team 14-1,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 29, 1934: Section 4, 2.

13 “Crescent Stars Trounce Chicago Negro Team, 4-0,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 15, 1934: 13.

14 baseball-reference.com/register/player.cgi?id=parker002tom.

15Holway, 346.

16 Ibid.

17seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?ID=1954.

18 ”N.O. Stars Will Play Birmingham in Sunday Games,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 8, 1941: Section 4, 2.

19 “N.O. Stars Down Red Caps Twice in Negro A.L. Bill,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 10, 1941: 11.

20 “N.O. St. Louis ‘9,’ Black Barons to Play Here Today,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 15, 1941: Section 4, 4.

21 ”NNL Orders Starks and Williams to Yankees,” Afro American, July 3, 1943: 23.

22cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Served_in_WWII.htm. No statistics are available for Parker’s time with the New York Cubans; however, the fact that he played for them – as well as the New York Black Yankees – is further corroborated by an article in the Baltimore Afro-American from May 1, 1948 (see Note 23 below).

23 ”Harrismen Launch Season Against Elites, Cubans,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 1, 1948: 29.

24 Barry Swanton. The ManDak League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2006), 5.

25Swanton, 147.

26Riley, 603.

27 Ibid.

Full Name

Tom Parker

Born

February 12, 1912 at Alexandria, LA (US)

Died

October 14, 1964 at Alexandria, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.