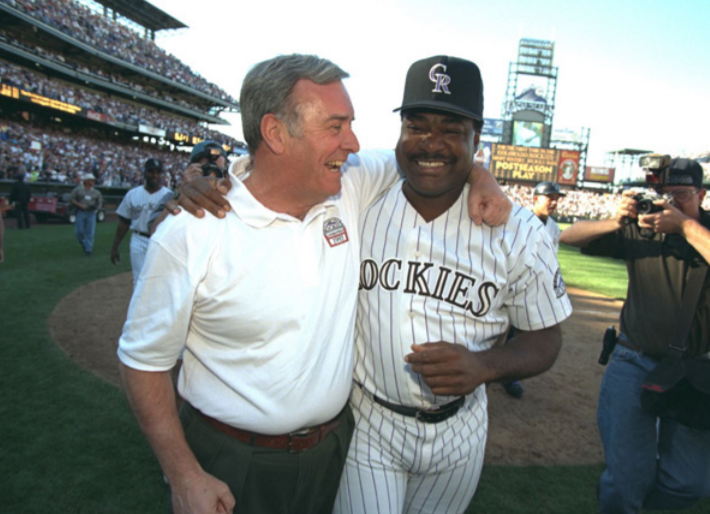

Jerry McMorris

“I’ll never forget the experience of going to spring training for the first time. Then, there was our first opening day against the Mets in New York. We came back to Denver for our first home game and Eric Young hit the home run leading off the bottom of the first inning. The home run and the great crowd were huge. Then fast forward to the opening game in Coors Field, making the playoffs in 1995 and our All-Star Game in 1998. All of those things were great for Denver.” — Jerry McMorris1

“I’ll never forget the experience of going to spring training for the first time. Then, there was our first opening day against the Mets in New York. We came back to Denver for our first home game and Eric Young hit the home run leading off the bottom of the first inning. The home run and the great crowd were huge. Then fast forward to the opening game in Coors Field, making the playoffs in 1995 and our All-Star Game in 1998. All of those things were great for Denver.” — Jerry McMorris1

Jerry McMorris knew what a championship baseball team looked like because he had been on one. In Little League. “I played first base,” the future millionaire entrepreneur and baseball team owner said, referring back to when he was 12. “I was tall and not especially quick of foot, so that’s where they put me.”2 He certainly wasn’t going to make money playing baseball. Instead, he started his own trucking company and three decades later was a successful businessman with enough money to buy a “major-league baseball team everybody in Colorado can be proud of,”3 he promised. He discovered building a championship team wasn’t anything like Little League, and running a baseball team wasn’t like running a trucking company. But both Colorado and baseball itself needed Jerry and his business know-how when it seemed the team wouldn’t even get off the ground, and the 1994 players strike threatened to dig baseball’s grave. McMorris, always exuding confidence, guided the Colorado Rockies through their first decade of existence and put the Mile High City on the baseball map.

Jerry McMorris was a baseball fan at heart and loved the American West, with its culture and traditions. He was a small part of the original ownership group of the Colorado Rockies, who were awarded an expansion franchise in 1991. When the major partners of the group were involved in legal and financial trouble and it looked as if Denver would lose its new franchise before it even started, McMorris stepped up at the eleventh hour to take control. McMorris can be called the savior of the Colorado Rockies; it might not have existed if not for him. He helped create not only an expansion franchise but also a team that was the talk of baseball in the 1990s. The Rockies led all of baseball in attendance from 1993 to 1999, made the postseason in just their third year of existence, and were often seen on baseball highlights slamming home runs consistently through the mountain air. But as fans and sportswriters regularly do with club owners, McMorris was criticized for what he did or didn’t do to get the club to the next level. Quality pitching was hard to find and McMorris’s record-breaking contracts to top pitchers couldn’t stop their ERAs from soaring like mountain peaks. But it wasn’t for lack of trying, and the Rockies in their infancy were led by a pioneer who was “a man more inclined to set a trend than follow a crowd.”4

“Jerry quickly established himself as a leader within our industry,” Commissioner Bud Selig said, “playing a key role on a number of our committees and serving not only the Rockies franchise but all of Major League Baseball very well.”5

Jerry Dean McMorris was born on October 9, 1940, in Rock Island, Illinois, to Donn and Evelyn McMorris. Both parents were from Illinois. Later siblings included a brother, Jeffrey, and a sister, Caryljo. At the 1940 census, Evelyn worked for a rubber boot manufacturer. Donn was a truck driver and would spend his career in the trucking industry. He drove for the Denver-Chicago (D-C) Trucking Company and worked his way up to vice president of the company. His upward mobility created a transient life for the family, and young Jerry lived in Iowa, Denver, Nebraska, Minnesota, Ohio, and Denver again by the time he reached his junior year at Denver’s Cathedral High School. Always being the new kid in class probably made him the success he was in the business world. “I wonder if that didn’t have a long-term effect on my life,” McMorris pondered. “I found it easier to go in and meet people than most men do.”6 “He was a very smart person,” his future wife, Mary, remembered. “He was a total ‘A’ personality. He just had a certain charisma when he walked into the room.” Mary remembered being “swept off my feet” at a young age as even then Jerry “was so positive and knew exactly what he was going to do with his life.”7

He loved the New York Yankees, and despite the distance from New York, McMorris felt a connection through the Denver Bears, a Yankees minor-league affiliate. He played baseball for Cathedral and fondly remembered his coach, Cobe Jones. “I remember he hollered a lot, and I got my share,” McMorris recalled. “He was a taskmaster, but he was a healthy influence on my life, because he made us aware that he expected me to do my best.”8

When he was 19, Jerry attended the University of Colorado and worked for D-C Trucking in the summer. He brought some ideas on how to improve the company to his father. “If you’re so smart, you should go into business for yourself,” his father told him. So Jerry did. He borrowed money, bought three trucks and established Westway Motor Freight trucking company. He began a relationship with the Adolph Coors Company and transported beer from the Coors Brewing Company in Golden, Colorado, to Denver. The energetic Jerry would haul beer, answer the phones, and change flat tires from sunup to sundown, believing no time in the day should be wasted. He later bought out Northeast Trucking and the combined companies were then called Northwest Transport.9 Jerry and Mary married in 1962.10

In 1965, he and his father merged, forming NationsWay Transport.11

In 1979 the McMorris family moved from Denver to a farm in Timnath, Colorado, an hour north of the city. Jerry and Mary had three children. The farm grew to 1,300 acres12 and in 1982 he went into the cattle business. By the mid 1990s his Belvoir and Red Mountain ranches encompassed 53,000 acres from Colorado to Wyoming.13 There was no doubt McMorris was a man who loved the West. “Nothing strikes a chord in him like the sight of father and son riding side-by-side on a tractor,” wrote Jerry Crasnick in Baseball America. “Or a little boy, dressed in cowboy boots, jeans, workshirt and cap, chewing on a toothpick like dad. He figures it’s the closest life can come to a Norman Rockwell painting.”14

In August of 1990, Colorado Governor Roy Romer turned to McMorris when early attempts to land professional baseball in the Mile High City were stalled. John Dikeou, owner of the Denver Zephyrs minor-league team, had been influential in persuading major-league owners to consider the city for an expansion team and encouraging voters to approve a ballot measure to fund a new stadium.15 But Dikeou had to remove himself from the position while major-league baseball was still entertaining pleas for an expansion team from Miami, St. Petersburg, Buffalo, and Washington. McMorris had previously considered investing in a sports team. “We had talked about joining the Denver Broncos ownership many years ago, and we had talked about the Denver Nuggets,” McMorris said. “But the opportunity to help bring baseball to the area meant more to me, and I know it means more to the community than buying an existing franchise.”16

On July 5, 1991, team owners approved a National League expansion franchise for Denver and the Michael Monus/John Antonucci/Steve Ehrhart ownership group. Monus and Antonucci were Youngstown, Ohio, businessmen. Monus was the president of the discount drugstore chain Phar-Mor Inc. Antonucci was an Ohio beverage distributor. Ehrhart, a Denver-area businessman, became chief operating officer. These new general partners also had secured financing for the future home of the Rockies, Coors Field. But the future of the franchise was in doubt a year later when Monus was forced out as president of Phar-Mor amid charges of embezzlement. Monus was forced to resign his position with the Rockies, was later indicted on charges of fraud and embezzlement of $1 billion, and spent time in prison.17 All of this hit the fan on July 29, 1992, a mere nine months before Opening Day. Monus and Antonucci’s $20 million investment was mainly through loans and not cash. An unsung hero in this story is Denver attorney Paul Jacobs, who on the very day Monus confessed his wrongdoings, had the Monus family transfer $10 million of stock in the team to himself and team accountant Stephen Kurtz. The Antonucci $10 million investment was also “bad money” since it was linked with Monus. So Jacobs arrived at the National League’s New York office to meet with NL President Bill White and Commissioner Fay Vincent, saying he now owned the team but didn’t have the $20 million needed.18

Enter McMorris, who was one of eight limited partners in the ownership group, having paid $7 million of the necessary $95 million expansion fee. McMorris was the limited partner to step up into a leadership role to keep the franchise afloat. He not only had to try to figure out a way to make up the shortfall, but also organize a new ownership team. Yet his optimism was apparent from the beginning. “The Colorado partners, once we get all the facts, will do what it takes to solve the problem,” he said. “There’s no reason for people here to be concerned, the commissioner to be concerned, or the league to be concerned. The Monus thing will not be a significant hurdle. I’ve talked to another partner, and knowing the character of the other families and businesses, I have no concerns. What I don’t want to see happen is for us to lose sight of the excellent management team they’ve put together.”19

“I remember I was in my backyard when Jerry came walking up,” Charlie Monfort remembered. Monfort and his brother Dick Monfort were part of a family that owned a meatpacking and distribution company in Greeley, Colorado. The company was later purchased by ConAgra Foods. “(Jerry) said: ‘We’ve got a problem. We’ve got to step up or we’re going to lose this franchise. What can you do?’ I said, ‘I’m in.’ But he’s the one who led the charge.”20 McMorris pledged half of the $20 million himself, and secured the rest through Monfort and Oren Benton, a Denver-area entrepreneur with holdings in uranium trading.21

“I believe it is fair to say without the efforts of Jerry, there may have never been major league baseball in Denver,” Dick Monfort said in 2012.22 “We have three new major partners — myself, Oren Benton, and Charles Monfort,” McMorris announced. “The major partners essentially have equal ownership positions, but I have been appointed chairman and chief executive officer of the general partnership and will represent our interest in the operation of the ownership group and related entities.”23 Coors Brewing Company was the fourth partner in the new ownership. Antonucci remained with the organization for a few more months, and Ehrhart became president of the Rockies Stadium Development Corporation, which was involved in the creation of Coors Field.

Other fine-tuning with just months to go before the 1993 season included the hiring of Bob Gebhard as general manager and Don Baylor as manager, as well as the expansion draft in November. “We’ve waited a long time for this,” McMorris said as he and Gebhard watched the first player workout at the first spring training in Tucson, Arizona. “This is a special day. Everybody here today is in on a little bit of history. It all starts right here, right now.”24 In less than two months, McMorris was in Shea Stadium in New York as the Rockies played on the first Opening Day in their history. They lost 3-0 and finished 0-2 on their brief season-opening series. Now they came home for their first home opener at Mile High Stadium. The legendary stadium had been home to Denver’s minor-league team since 1948, but because it shared space with the Denver Broncos of the National Football League, the left-field wall was adjusted to only 335 feet, a hitter’s paradise.25

McMorris addressed the team before it took the field in front of a crowd of 80,227, the largest ever in the National League. “Guys, the sky’s the limit. The dreams are out there for you guys to chase. Here’s your opportunity.” “That was big for us,” Dante Bichette recalled. “I don’t think major-league baseball would have happened in Denver if not for him.”26 The energized team won that home opener over Montreal, 11-4, with leadoff batter Eric Young, the first Rockie to bat at home, homered in a four-run first inning. The team had plenty of offense. The 1993 Rockies finished third in the National League in batting average, fourth in runs per game, tied for fourth in runs scored, and third in slugging percentage. The thin mountain air contributed to their power and huge discrepancies were evident in their home/away averages. The Rockies had a higher batting average (.306/.240), scored more runs (489/269), produced more RBIs (449/255), and had more total bases (1,328/1,001) at home by wide margins than they did on the road. But the opposite was also true. Colorado pitchers had a collective ERA nearly a run higher at home than on the road (5.87/4.99), far more runs allowed (551/416), and more home runs allowed (107/74).

McMorris was determined to show the multitude of fans (the brand-new Rockies drew a major-league record of 4,483,350 or 55,350 per game) he was determined to improve the troubled pitching staff. In July, the Rockies acquired veteran starting pitchers Bruce Hurst and Greg Harris in a trade with the San Diego Padres. “Our fans deserve to have a winner,” McMorris said. “If we aren’t willing to take some financial gambles in our position, then shame on us.”27 But the salaries were high and the players were a gamble. The 35-year-old Hurst never won a game for the Rockies; Harris suffered a horrendous 1-8 with a 6.50 ERA. “Regrets? None,” McMorris said. “I don’t even have any second thoughts.”28 The Rockies’ inaugural season saw them finish 67-95, in sixth place in the National League West.

McMorris was named the 1993 Business Leader of the Year by the Colorado Association of Commerce and Industry.29 The 1994 season, in which both leagues divided into three divisions with a wild-card playoff team, saw the Rockies improve to third place despite the worst ERA in the league (5.15). When player David Nied’s son was born prematurely in New York City and needed to be transported to Denver by Air Ambulance, McMorris paid the $13,000 bill. “They were in a tough, tough deal, and I was in a position where we could at least cushion that a little. So that’s what we decided to do,” he said.30

McMorris would have a major role in baseball beyond the Rockies franchise. The 1994 season has forever been a black mark on the game. With the collective-bargaining contract up for renegotiation, the owners, who had colluded to limit the signing of free agents in previous years, sought to control soaring salaries via a salary cap, a revenue-sharing plan, and limits on the power of free agents. With little progress toward settlement, the players union struck on August 12. Many expected the situation to be resolved shortly, but the remainder of the season and postseason were canceled. As a late December deadline for the owners to impose a salary cap approached, the owners negotiating committee called on McMorris to make their last good-faith effort before imposing the cap.31 Acting Commissioner Bud Selig remarked, “Jerry is the best person to come.”32

“Both parties are probing and trying to find a way,” McMorris said after a three-hour meeting that ended in the wee hours of the morning. “My sense is if we’re deadlocked again on Thursday, there won’t be any flexibility. If we can break the deadlock and get the thing moving, we shouldn’t need to go beyond Thursday [December 22].” McMorris had experience negotiating with the Teamsters Union and players had respect for his demeanor and manner. “He’s a nice guy who’s sometimes shrewd,” said Don Baylor, the Rockies manager. “He’s confident he can get it done by negotiating. That’s how Jerry looks at himself. He’s not trying to intimidate; he’s trying to negotiate. His attitude is, ‘We can work it out.’” “He’s approachable,” said David Cone, a player representative. “We admire him as a second-year owner who has the guts to speak his mind.”33 This was the Jerry his wife, Mary, knew so well: “He could see a path to negotiating when no one else could.”34

McMorris said his previous success in negotiating “has had something to do with treating people with dignity and respect, which is always how I conduct myself. I think that’s important. A proper relationship with everybody is important. And certainly your relationship with your employees and your associates in any business is. This sport is no different.”35

In 1994, NW Transport changed its name to NationsWay Transport to better reflect a national company that recently opened 28 new freight terminals, mostly in the Northeast and Southeast. This expansion was possible when St. Johnsbury Truck Lines, a New England-based service McMorris had as a marketing partner, went out of business and McMorris took over the routes.36 By 1995 NationsWay saw profits around $400 million, had 6,500 employees and 13,000 pieces of equipment, and had expanded into Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.37 But McMorris was still known as an everyday, caring individual who contributed to his church: St. Benedict’s Church in Florence, Colorado, and let employees just call him Jerry. “I could get along without the attention,” McMorris said in 1995. “It’s something I can handle, but I don’t thrive on it.”38

In January 1995 Baseball America listed McMorris as number three among the 25 most influential people in baseball. “No one has risen as far, as fast as McMorris,” the publication wrote. “He is already an important member of the owners’ negotiation committee, and many think he’ll be the key to straightening out the mess in baseball. McMorris looks at the big picture better than other owners and is a calming force in a sea of hotheads.”39 His net worth, including his trucking business, farm, and ranch as well as the Rockies, was estimated at $100 million.40

The 1995 season was a landmark season for the franchise. The team unveiled Coors Field as the new home of the Rockies, and also made the playoffs for the first time. Coors Field was the first baseball-only park built in the National League since Dodger Stadium in 1962. A downtown-friendly stadium would easily become the most hitter-friendly stadium in baseball and the biggest nightmare for pitchers. The design placed outfield fences farther back, in light of the history of home runs flying out of Mile High Stadium. But this only meant more doubles and triples. Left field was 347 feet, left-center 390 feet, and the deepest part of right-center 424 feet. Because of the enormous crowds at Mile High, the original 43,800 seats planned for Coors Field were increased to 50,200.41

The first game at Coors Field was a spring-training contest against the New York Yankees on March 31, 1995, even as the strike still lingered and replacement players were brought in. The absence of star players didn’t dampen the enthusiasm, however; the shiny new stadium was the star of the show. “This is a special day for the whole region,” McMorris said. “After waiting more than 30 years, we now have the most unique urban ballpark in the majors.”42 Baseball lifer Don Zimmer, now a Rockies coach, said, “Were this game not in a brand-new park, it’d be just another spring-training game. But when nearly 50,000 people come out, that’s special.”43 In the crowd was Buck O’Neil, the legendary Negro League player. “I’ve played in some great parks — even in old Yankee Stadium,” he said. “But nothing like this.”44

Fans were obviously eager for the regular players to return and the gloomy strike to end. That announcement came the very next day. Having been rebuffed by the courts, the owners couldn’t garner enough votes to continue a lockout, and agreed to the union’s offer to return to work. The season would be limited to 144 games instead of 162, but replacement players never set foot on the diamond for an actual regular-season game. Baseball was finally back. “I hope we’ll be very aggressive and get to the table very quickly,” McMorris said. “We’ve both proven how strong we are, and I think we’ve severely damaged our game.”45 Nevertheless, McMorris invested money to improve the team, giving $35.1 million for free-agent pitcher Bill Swift and free-agent outfielder Larry Walker. “There’s only one reason we can do this,” McMorris said. “The fan support in Denver. Who would have ever known that they would have stepped up like they did? And we’re trying to give them back a financial commitment. We think we’ve made more advancement in a shorter period of time than any other expansion franchise.”46

The first Opening Day at Coors Field, on April 26, harkened back to the beginnings of the franchise two years earlier. Eric Young had homered in the first Rockies at-bat in 1993 and now it was a walk-off home run by Dante Bichette in the 14th inning to christen Coors Field as the Rockies prevailed in the cold opener, 11-9. “This was exciting,” McMorris said. “The weather was cold and it was gratifying to see the fans still there at the end.”47 They would also have a walk-off win the next day, 8-7. Their two initial games set a tone: The pitching was again bad at home, but the bats were ferocious. The Rockies led the NL in home runs (200), RBIs (749), slugging percentage (.471), and batting average (.282). At home they batted .316 (134 home runs), on the road, .247 (66 homers). The Rockies’ pitching was again last in the NL in ERA at 4.97 (6.17 at home, 3.71 on the road). But it was enough to get them into the playoffs. Walker hit 36 home runs with 101 RBIs and was joined by teammates with similar numbers: Andres Galarraga (31-106), Vinny Castilla (32-90), and Bichette (40-128). “Tears of joy,” McMorris said as the club clinched a postseason berth. “It was a very emotional time for me. This is why we wanted to have baseball here in the first place.”48 Fittingly, the Rockies clinched by winning the season finale 10-9 after trailing 8-2. “The 30-year wait to get major-league baseball here gave a lot of people the opportunity to be part of this.”49 It was their only playoff appearance during the McMorris ownership era.

Jerry and Mary had a son, Michael Dean McMorris, who was born in 1964. At 14 months Michael was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis and was not expected to live past the age of 2. He survived and thrived, however, becoming a high-school athlete who loved to scuba-dive, hike, and ski. He graduated from Colorado State University in 1988 and while a student assisted the CSU football program in videotape, budgeting, and recruitment. After college Michael worked with his father in the trucking business, and then joined the Rockies as director of operating services. Despite his constant need for medical and physical care, Michael lived to age 32, succumbing to the disease in 1996. The Rockies wore the initials MDM on their sleeves during the season.50 “Mike was loved by everybody who took care of him. He was a role model for people who have to face adversity,” said his physician, Dr. Lawrence Kline.51 The research for a cure for the disease goes forward in his name at the Mike McMorris Cystic Fibrosis Research and Care Center at Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora, Colorado. The center is “the largest CF clinical care center in the United States,” according to its website.52 “We hope that funding this center in celebration of Mike’s life will help conquer the disease once and for all,” McMorris said at the center’s grand opening in 1998. Mary echoed his sentiments and applauded the medical advances on the disease. “We’re quite encouraged by the progress,” she said, “but at the same time, we’re disappointed that we’re not really solving the problems of children who have it now.”53

Another son, Scott McMorris, attended Colorado University.

The Rockies had back-to-back third-place finishes of 83-79 records in 1996-1997, experiencing the same problems with pitchers. The Rockies didn’t even have a starting pitcher with 10 wins in 1997. After two offseasons of no blockbuster pitcher signings, McMorris dug into his pockets again and acquired free-agent pitcher Darryl Kile.

Coors Field hosted the All-Star Game on July 7, 1998. Hometown hero Walker started in center field, batting seventh. Appropriately, it was the highest-scoring All-Star Game in history, with the American League winning 13-8 before a crowd of 51,267. McMorris summarized the occasion succinctly enough: “I think we put on a good show.”54 A 77-85 season by the Rockies, however, soured the rest of the season and it cost Baylor the managerial job he had held since day one of the franchise. “I personally will accept a large part of the responsibility for our disappointments,” McMorris said, deflecting the blame from Baylor. “This issue wasn’t to point fingers. In the end, the players are the ones who have to play. We know that. We felt that the quickest way to get to the level we want was a change in chemistry.”55

Before the 1999 season, Commissioner Selig appointed McMorris to a panel to discuss the issue of revenue-sharing and a player salary cap. Also on the committee were author George Will, representatives of the MLBPA, and Yale academics. That offseason, the Los Angeles Dodgers had signed free agent Kevin Brown to a $105 million, seven-year contract. McMorris was firm in the belief that baseball needed to overhaul how it divided TV revenue “so that each city has some chance of winning.” “We’re not owned by a [Rupert] Murdoch, Disney, or Ted Turner, and baseball can’t afford the kind of imbalance where the Dodgers’ Kevin Brown alone makes twice the Montreal Expos’ entire payroll.” Citing the salary-cap system of the National Football League, where small-market teams could compete against the larger markets, McMorris said baseball should adopt a system “to put a brake on those who simply want to spend their way to the moon.”56

Jim Leyland, considered the best manager available and the skipper who had led Florida to a world title in 1997, became the Rockies’ manager in 1999. “He was a winner,” McMorris said. “And we had a sense that he liked Coors Field, and he liked it in Colorado. Jim has a different approach in the way he manages. And his approach is enhanced by the World Series ring he’s won as a manager.”57 Mike Klis of the Denver Post reported that the Rockies’ payroll jumped 14.7 percent to $59.7 million, a 707 percent increase over the $8.8 million payroll on McMorris’s first Opening Day, in 1993. “And I’m the cheapskate,” McMorris said, referring to criticisms that he was unwilling to spend money.58 At the top of the payroll was Kile, the expected ace of the staff, who at over $8 million a year led the league in losses (17) with a 5.20 ERA in 1998. Yet the biggest expense would come just days later. Walker signed a six-year extension for $75 million, or $12.5 million per season. Recognizing that he had to spend to compete, McMorris said, “What it really came down to is we are constantly being pressured on what players are being paid in New York and Los Angeles. But not everybody wants to play in New York and Los Angeles.”59

Depressingly, the 1999 season was another poor one for McMorris (72-90, fifth place), and though the Rockies led baseball in attendance for the seventh straight year, it was down by 300,000 from the year before. Leyland could not figure out what to do with the pitching staff. The Rockies’ team ERA was 6.01 and they surrendered the most home runs in the league (237). Yet once again their hitters led the league in batting average (.288) and home runs (223). Bob Gebhard, who had built the team from scratch, resigned as GM. “Bob Gebhard was the heart and soul of this franchise,” McMorris said. “He’s a stand-up guy. But I could tell today that he was totally drained and beat. It wore on him. It was showing. He was in a tough spot. He couldn’t effectively handle his job, especially from the All-Star Game on. But he worked day and night for this organization.”60 Leyland also departed after the season, and Buddy Bell became the new manager.

The year was also a difficult one financially for McMorris. NationsWay had been struggling and needed to be restructured in 1997, slashing routes and returning to a regional service. The $450 million in revenue in 1996 represented an 11 percent decline.61 The restructuring plan McMorris enacted was only temporary, however, and NationsWay filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in May of 1999. “A bankruptcy judge in Phoenix is now the CEO of NationsWay,” McMorris said.62 “This was a challenge bigger than I could find a solution for,” he said, referring to the $19 million debt the company accrued, much of it through the failure to make payments to the employee pension fund. McMorris blamed deregulation in the industry, which allowed smaller trucking companies to eat into NationsWay profits over the previous five years. “The fundamental problem is a tough, competitive industry that has had inadequate profits,” McMorris said. “The reality was simple — we were not producing a profit.”63 More than 3,000 employees lost their jobs. By contrast, WestWay Express, a smaller trucking company McMorris owned, was thriving.64

The reality in the business world is that companies do “go under” and people do lose their livelihoods. But when you are one of those hard-working employees who has a family to support, and your boss, who filed bankruptcy for the company, is the same person who gave a $12-million-a-year contract to Larry Walker, it is understandable that hard feelings persisted. Such was the image problem McMorris suffered. On the one hand, NationsWay was in a hole, but the Rockies, his other, unrelated business, were prospering. Members of the Teamsters began picketing outside Coors Field. “When the owner of your company pays the Rockies millions and millions of dollars and they can’t pay us, it makes you a little hot under the collar,” said Valerie Whiddon, a NationsWay employee.65 “I’m sure that my owning the Rockies is a lightning rod for criticism from people who don’t understand that the Rockies are a completely separate legal entity with completely different partners,” McMorris said. “What we decided we wanted to pay to keep Larry Walker doesn’t have a darned thing to do with wages being competitive in the trucking industry. The [trucking] business has struggled for five years, and it hasn’t changed the Rockies’ foundation or the other things this organization stands for. I hope everyone can get on with their lives with a minimal amount of disturbance. But it is what it is. It’s very distasteful for everyone. We feel very sorry for everyone involved.”66 Most business owners don’t have such a high profile as that of a baseball-team owner, or have such a source of revenue, something his truckers took notice of in terms of income disparity. “I’ve had drivers ask me over the years how I can pay these type of wages when not one of these ballplayers can drive a truck over Loveland Pass, let alone do it with chains on. Well, nobody’s ever paid me to watch those guys chain up and go over Loveland Pass.”67

In response to the financial hit, McMorris sold all but $8.5 million of his investment to the Monfort brothers, increasing their ownership stake to 46.3 percent of the club.68

The 2000 season saw the Rockies finish over .500 (82-80) with an improved fourth-place finish, and the team ERA (5.26) actually wasn’t the worst in baseball. Their .294 batting average still topped the NL. To build on the success, McMorris and new GM Dan O’Dowd gave a $121 million contract to free-agent pitcher Mike Hampton for eight years, the largest contract in baseball history to that point. Just days earlier, they had also opened their wallet for free-agent pitcher Denny Neagle for $51.5 million for five years. Beaming at the press conference over the $172.5 million paid for two pitchers, McMorris took congratulatory handshakes, but then uttered an off-hand remark, “If it doesn’t work out …”69

It didn’t. Hampton’s ERA soared to 5.41 in 2001 and in 2002 he finished 7-15 with a 6.15 ERA. The Rockies (73-89) finished in the basement in 2001. Neagle was 9-8 with a 5.38 ERA. “We really thought that we would be contenders,” McMorris stated.70 “The heralded free-agent signings were a flop and a failure and a fiasco of epic proportions,” wrote Woody Paige in the Denver Post two years later.71

After the 2001 season, McMorris stepped aside as team president while remaining CEO. Keli McGregor became team president and handled day-to-day operations. McMorris was content with the move. “It means I won’t have to be at the office at 7 every morning,” McMorris said. “But I’ll still be around. In today’s economic climate, with the salaries the way they are, ownership has to be involved in the major decisions made by the baseball people. The difference now is we’ll become involved only after Keli and Dan and Buddy sort through them first.”72 In 2002, he relinquished his title of CEO and chairman to Charlie Monfort, and remained as vice chairman.

The Rockies again went 73-89 in 2002, a fourth-place finish that was gasoline on the fire for fans and sportswriters clamoring for a change in the front office. “Everything that’s wrong with the Rockies starts at the top,” wrote Mark Kiszla of the Denver Post. “The primary aim is to find a way to dump the salaries of pitchers Denny Neagle and Hampton. They were $175 million mistakes that proved McMorris and the Monfort brothers lack the deep pockets to cover the inevitable errors of free agency. Compounding their lousy investments, the Rockies futilely try to cover their blunders with nickels and dimes. Hampton, Neagle, Walker and first baseman Todd Helton devour a staggering 65 percent of the team’s budget for players.”73 McMorris was an architect who helped build the club and see it rise to the playoffs in a short time. Now he had watched the team have four losing seasons over the last seven, never finishing higher than third. “Once upon a time,” Kiszla wrote, “a Colorado trucking magnate rode to the rescue of a National League expansion franchise in need of a jump-start. McMorris, however, has driven baseball in Colorado as far as a man of his resources can go. He and the Rockies would be best served by unloading the team to new ownership, and hauling his well-earned profits into the sunset.”74

The Rockies finished two more poor seasons in 2003-2004 (74-88, 68-94), and attendance was now far from the top in the National League. In November of 2004, McMorris was removed as vice chairman by the Monfort brothers. McMorris retained his 12.4 percent financial stake in the ownership group but no longer had voting rights. “I didn’t decide it,” he said. “I’ve put 12 years in helping to bring major-league baseball to Colorado, building the franchise and working with what was in the best interest of major-league baseball. I’ve given it my best effort. I don’t understand any of this.”75

In December of 2005, the Monfort brothers bought out McMorris’s 42.5 percent share of the general partnership. McMorris received between $17 million and $20 million for his remaining $8.5 million investment. Satisfied with the deal, he took time to reflect on his time running the ballclub. “Getting Coors Field built was a big accomplishment for our franchise. And I enjoyed all of the relationships with the fans and players,” McMorris said. “I am just sorry we weren’t able to put the pitching together to maintain a consistent run (at the playoffs). It wasn’t because of a lack of effort or a lack of money. Those first few years were as special a time as anyone has seen in all of sports.”76 By this time, McMorris acknowledged that his time in baseball ownership had drawn to a close. “I didn’t get into baseball thinking it would be the rest of my life,” he said. “The plan all along was for Charlie (Monfort) to assume the leadership role.”77

McMorris, his days as a trucking magnate and baseball executive over, returned to where his heart always was: a ranch in the west. He had been involved with the Western Stock Show Association, serving as chairman for six years and on the executive committee for 18 years. “It was an honor to learn from Jerry and witness his passion for the Western way of life and the values we at the Stock Show represent,” said Paul Andrews, president and CEO of the show.78 McMorris continued to serve the Denver community as vice chairman of the Denver Police Foundation and a member of the board of directors of the Poudre Valley Fire Authority.79 He never settled into a retirement role, which Mary said didn’t fit his energetic style. “His entertainment was taking on a new business deal,” she said. “He was a businessman, and he thrived.”80

While McMorris was ranching, the Rockies put together a memorable 2007 season. The club was largely based on home-grown talent like Matt Holiday, who paid tribute to McMorris for not giving up on him when he was struggling in the minor leagues. “He was always vocal about his support of me and thinking I would be a good player,” Holliday said. “He was a big reason why I stayed with baseball.”81 McMorris turned out to Coors Field to watch the Rockies advance to the National League Championship Series. “I am extremely pleased for everybody involved with the franchise,” he said. “I feel great about what is going on. This is how it is supposed to be.”82 The Rockies won the National League pennant, but lost to the Boston Red Sox in the World Series.

McMorris was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame in 2009. In his induction speech, McMorris’s interests in baseball and the American West appropriately came together in a story he told of Gene Autry, the American icon and owner of the California Angels. Meeting Autry at an owners’ meeting, Autry told him how he voted for Denver to be a franchise because “Colorado always treated him No.1.”83

Jerry McMorris died on May 8, 2012, at the Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Colorado, after a lengthy battle with pancreatic cancer. He was survived by his wife, Mary, his two children, and six grandchildren. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Wheat Ridge, Colorado. Players lined up at Coors Field before the game on May 16, and a video tribute was aired on the JumboTron. Another video tribute aired during the game, and the crowd gave a standing ovation.84 Mary, who as of 2017 was still attending one Rockies game per month, noted how pleased she was to have been a part of the Rockies franchise and the friendships she made.

“I believe it is fair to say without the efforts of Jerry, there may have never been major-league baseball in Denver. He will be greatly missed by us all,” Dick Monfort said.85 Charlie Monfort summarized the McMorris legacy well: “Jerry McMorris will always have a special place in the history of the Colorado Rockies.”

This biography appears in “Major League Baseball A Mile High: The First Quarter Century of the Colorado Rockies” (SABR, 2018), edited by Bill Nowlin and Paul T. Parker.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author benefited from the following sources:

Baseball-reference.com.

Jerry McMorris file from the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Irv Moss, “Catching up with Jerry McMorris — Running His Own Farm Club — Rockies Owner Exited Baseball Stage After 12 Years,” Denver Post, September 25, 2006: C-02.

2 Mark Kiszla, “McMorris May Be Man to Fuel Trust in Rockies,” Denver Post, August 8, 1992: 1D.

3 Ibid.

4 Jerry Crasnick, “A Driven Man,” Baseball America, May 29-June 11, 1995: 11.

5 “What Others Are Saying,” Denver Post, May 9, 2012: 3B.

6 Crasnick, “A Driven Man.”

7 Mary McMorris, phone interview with the author, November 10, 2017.

8 Irv Moss, “McMorris at Home as Owner — Rockies’ Principal Taps Local Roots,” Denver Post, October 27, 1992: 1D.

9 Irv Moss, “McMorris at Home as Owner.”

10 Mary McMorris interview.

11 Crasnick, “A Driven Man.”

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Irv Moss, “John Dikeou Played Role in Bringing Major-League Baseball to Denver,” Denver Post, March 31, 2015.

16 Irv Moss, “McMorris at Home as Owner.”

17 Gene Wojciechowski, “Rockies Born of Monus’ work, but He Never Saw His Baby Grow Up,” ESPN.com, October 23, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2017. https://espn.com/espn/columns/story?id=3074665&columnist=wojciechowski_gene&sportCat=mlb.

18 Mike Klis, “25 Years Ago: How Denver Attorney Paul Jacobs Helped Bring Major League Baseball to Denver,” KUSA News. Retrieved April 1, 2017. https://9news.com/news/25-years-ago-how-denver-attorney-paul-jacobs-helped-bring-major-league-baseball-to-denver/262421119.

19 Jim Armstrong, “Rockies Partners Pull Out — Phar-Mor’s Monuses Resign Amid FBI Investigation,” Denver Post, August 4, 1992: 1A.

20 Patrick Saunders, “Jerry McMorris, 1940-2012,” Denver Post, May 9, 2012: 1B.

21 “Oren Lee Benton,” Sioux City Journal, May 21, 2006. Retrieved March 19, 2017. https://siouxcityjournal.com/news/local/obituaries/oren-lee-benton/article_36ed878d-d068-5e42-92b8-129a717082a1.html

22 https://denverpost.com/2012/05/08/mcmorris-one-of-rockies-original-owners-dies/.

23 Irv Moss, “McMorris Running the Show,” Denver Post, September 3, 1992: 5D.

24 Jim Armstrong, “Rockies Spring to Life in First Workout — Special Day Quenches Major Thirst,” Denver Post, February 20, 1993: 1D.

25 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Co, 2006), 80.

26 Patrick Saunders, “Jerry McMorris, 1940-2012.”

27 Mark Kiszla, “Investment Pays Fans for Loyalty,” Denver Post, July 27, 1993: 1D.

28 Mark Kiszla, “Harris Hopes to Become Fixture in Future,” Denver Post, September 15, 1993: 3D.

29 “Spotlight on McMorris, CACI Winners,” Denver Post, July 19, 1993: 6C.

30 Jim Armstrong, “Rockies’ McMorris Is a Shy Samaritan,” Denver Post, September 18, 1994: B-4.

31 Cliff Corcoran, “Who Was Right, Who Was Wrong, and How it Helped Baseball,” Sports Illustrated, August 12, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2017. https://si.com/mlb/2014/08/12/1994-strike-bud-selig-orel-hershiser; Associated Press, “McMorris, One of Rockies’ Original Owners, Dies,” Denver Post, May 8, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

32 Claire Smith, “It’s Down to the Wire; McMorris Is at Plate,” New York Times, December 22, 1994.

33 Ibid.

34 Mary McMorris interview.

35 Claire Smith, “It’s Down to the Wire.”

36 Jeffrey Lieb, “NW Rolls Out National Name — McMorris Trucking Firm on the Road to Growth,” Denver Post, December 29, 1993: 1C.

37 Crasnick, “A Driven Man”; Smith, “It’s Down to the Wire.”

38 Crasnick, “A Driven Man.”

39 Quoted in Norm Clarke, “National Acclaim Rains on McMorris,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver), January 10, 1995: 2B.

40 Crasnick, “A Driven Man.”

41 Green Cathedrals, 81.

42 J. Sebastian Sinisi, “Coors Field Intoxicates Sports Fans,” Denver Post, April 1, 1995: AA-4.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Jerry Crasnick, “Ball Strike Over. Owners Approve April 26 Opener; Issues Unresolved,” Denver Post, April 3, 1995: A-1.

46 Woody Paige, “Rockies Lay Hefty Bet to Win Big-Ticket Talent,” Denver Post, April 9, 1995: B-1.

47 Irv Moss, “Ice Cold Coors. Coors Opener Packs Pizzazz at Finish,” Denver Post, April 27, 1995: D-12.

48 Hal Bodley, “Rockies’ Wild-Card Berth a Credit to McMorris, Fans,” article of unknown origin in McMorris’s Hall of Fame file.

49 Bodley, “Rockies’ Wild-Card Berth.”

50 Todd Phipers, “Rockies Mourn Loss of Mike McMorris,” Denver Post, March 31, 1996: CC-04.

51 “Michael Dean McMorris, 32, of California,” Denver Post, March 30, 1996.

52 https://childrenscolorado.org/doctors-and-departments/departments/breathing-institute/programs/cystic-fibrosis/, retrieved March 17, 2017.

53 Ann Schrader, “Cystic-Fibrosis Center Dedicated at Children’s,” Denver Post, October 21, 1998: B-01.

54 Woody Paige, “Baseball, the Rockies and Denver Can Be Proud,” Denver Post, July 8, 1998: AA-02.

55 Irv Moss, “No Ring, So Bell Tolls for Baylor,” Denver Post, September 29, 1998: D-06.

56 J. Sebastian Sinisi, “McMorris Favors Level Playing Field,” Denver Post, January 20, 1999: D-07.

57 Mike Klis, “It’s a Deal! Leyland Agrees to 3-year Pact,” Denver Post, October 6, 1998: D-01.

58 Mike Klis, “Rockies’ 1999 Payroll: Money Talks $59.736 Million Going to Players,” Denver Post, March 2, 1999: D-08.

59 Mike Klis, “Walker Strikes a Deal: $75 Million for Six Years,” Denver Post, March 5, 1999: D-01.

60 Irv Moss, “End of an Era For the Colorado Rockies; Given a Choice, Gebhart Resigns; Sources Say GM Was Gone Either Way,” Denver Post, August 21, 1999: C-01.

61 Henry Dubroff, “McMorris gets NW Transport Moving Again,” Denver Business Journal, October 5, 1997. Retrieved March 17, 2017, https://bizjournals.com/denver/stories/1997/10/06/newscolumn1.html.

62 Gregory S. Johnson, “NationsWay Transport Goes Out of Business,” Journal of Commerce, May 23, 1999. Retrieved March 17, 2017, https://joc.com/nationsway-transport-goes-out-business_19990523.html.

63 Donald Blount and Jeffrey Leib, “McMorris Lost Race Against Time,” Denver Post, May 22, 1999. Retrieved March 18, 2017, https://extras.denverpost.com/business/biz0522.htm.

64 Jeffrey Lieb, “The Way to Go: Westway Thrives While Sister Firm in Bankruptcy,” Denver Post, June 27, 1999: J-01.

65 Bill King, “Rockies Owner Draws Fire,” Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal, June 7-13, 1999: 13.

66 Ibid.

67 King; Located on the Continental Divide, Loveland Pass (US Route 6) is considered to be the highest mountain pass in the world (nearly 12,000 feet above sea level) to stay open even during the winter months. Weather conditions often force the road to be closed, and its hairpin turns and steep grades can make driving treacherous, especially for truck drivers. https://dangerousroads.org/north-america/usa/62-loveland-pass-usa.html.

68 Mike Klis, “Rockies Fire McMorris as Their Vice Chairman. The Former No. 1 Boss Retains His Stake With the Franchise, but His Voting Rights Have Been Lifted,” Denver Post, November 10, 2004: D-01.

69 Woody Paige, “Rockies Run Off M Factor,” Denver Post, November 14, 2004: BB-01.

70 Tony E. Renck, “Rockies’ Motto: Team Comes First,” Denver Post, February 10, 2002: D-02.

71 Paige, “Rockies Run Off M Factor.”

72 Mike Klis, “McMorris Hands Off Daily Duties,” Denver Post, October 19, 2001: D-01.

73 Mark Kiszla, “M&M Boys Should Contemplate Selling,” Denver Post, September 22, 2002: C-01.

74 Ibid.

75 Klis, “Rockies Fire McMorris as Their Vice Chairman.”

76 Troy E. Renck, “Monforts Buy out McMorris — The Team’s Former CEO Was Instrumental in Bringing Major-League Baseball to Denver,” Denver Post, December 16, 2005: D-02.

77 Tracy Ringolsby, “Former Rockies’ Owner’s Heart Still in It,” Rocky Mountain News, October 12, 2007.

78 “McMorris, One of Rockies’ Original Owners, Dies.”

79 Moss, “Catching Up with Jerry McMorris.”

80 Mary McMorris interview.

81 Irv Moss, “Farm Teams Yield Top Crop — Homegrown Talent Forms the Foundation of the Team That Is Excited About the Future,” Denver Post, October 3, 2007: R-08.

82 Ringolsby, “Former Rockies’ Owner’s Heart.”

83 Irv Moss, “Regier Gives Inspiring Speech — Disabled Athlete Among Honorees at Hall of Fame Induction Banquet,” Denver Post, April 15, 2009: C-08.

84 Troy E. Renck, “Moyer Inspires With Effort, Not Age — That’s All People Want,” Denver Post, May 17, 2012: 1B.

85 “What Others Are Saying.”

Full Name

McMorris

Born

October 9, 1940 at Rock Island, IL (US)

Died

May 8, 2012 at Aurora, CO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.