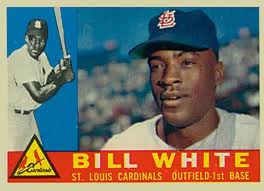

Bill White

Bill White spent 51 years in a game he didn’t love. The eight-time All-Star became the first black play-by-play broadcaster for a major-league team and the first black president of a major sports league. He railed against racism in baseball, though he acknowledged that, even as National League president, he couldn’t do much about it.

Bill White spent 51 years in a game he didn’t love. The eight-time All-Star became the first black play-by-play broadcaster for a major-league team and the first black president of a major sports league. He railed against racism in baseball, though he acknowledged that, even as National League president, he couldn’t do much about it.

William DeKova White was born on January 28, 1934. In his autobiography White gives his birthplace as Paxton, Florida, a crossroads town in the state’s Panhandle near the Alabama border. Baseball encyclopedias say he was born in Lakewood, another hamlet just three miles east. White never knew his father, Penner White, and was raised by his grandmother, Tamar Young, and his mother, Edna Mae Young. His first home was a shack with no electricity or indoor plumbing. When Bill was 3 years old, his mother joined the black migration northward, moving to Warren, Ohio, where several relatives worked at the Republic Steel plant. The family lived in a segregated public housing project. His mother worked as a housecleaner until she went to secretarial school and got a civilian job with the US Air Force. While her work moved her around the country, she left her son in Warren with his grandmother.

Bill attended the mostly white Warren G. Harding High School. When he was elected senior class president, the principal ended the tradition of having the president dance with the prom queen, because the queen was white. Bill lettered in football, basketball, and baseball, but he said later, “I was first string in nothing. I was about the third-string halfback in football, and in basketball I was the tenth man on a ten-man team.”1

Despite his later memory, he attracted two football scholarship offers. Instead, he went to tiny Hiram College in Hiram, Ohio, because he liked the school’s pre-med program and was offered an academic scholarship. A left-handed first baseman, White called himself an average baseball player in college. But he hit two home runs in the championship game of the National Amateur Baseball Federation tournament at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. A bird-dog scout for the New York Giants, Alan Fey, invited White to Pittsburgh to work out for manager Leo Durocher. He hit a few balls over Forbes Field’s right-field wall before Durocher hustled him into the locker room so Pirates general manager Branch Rickey wouldn’t spot him. To his surprise, White was offered a contract with a $1,000 bonus. He said no. His family had always preached the importance of a college education and he didn’t want to disappoint them. When Durocher was called in to close the deal, the 18-year-old said he needed $2,500 to finish college. “Okay, kid, you’ve got it,” the manager replied. He also threw in a new pair of spikes.2 White’s mother agreed to let him sign only after he promised to finish college.

Durocher took White to spring training with the big-league club in Phoenix in 1953 and made the professional rookie his personal project. Some other players called him “Leo’s little bobo.” White remembered his first encounter with segregation when he tried to go to a movie. The theater manager turned him away because the building had no balcony. He didn’t know that black patrons were only allowed to sit in the balcony in many theaters. His roommate, the veteran Monte Irvin, counseled him, “Don’t rock the boat. Someday all this is going to change.”3

The Giants sent White to Danville, Virginia, where he was the only black player in the Class B Carolina League. That made him a target for some white fans; he said it was the first time he had been called “nigger” to his face. He asked to be transferred to a team in the North, but he was leading Danville in hitting and the manager wouldn’t part with him.4 His temper erupted one night in Burlington, North Carolina, when he flashed his middle finger at an abusive crowd. His white teammates escorted him to the bus behind a shield of bats and the Danville club left town in a hail of rocks. He recalled that year as “probably the worst time of my life.”5 He answered the abuse with his bat, hitting 20 home runs with a .298 average.

White planned to give baseball three or four years and go for his medical degree if he didn’t make the majors. Promoted to the Class A Western League in 1954, he hit 30 homers and stole 40 bases for Sioux City Iowa, then followed with 20 homers for Dallas in the Double-A Texas League the next year. He had returned to Hiram College every fall, but in 1955 he played winter ball and left school for good, to his mother’s everlasting disappointment.

During spring training in Arizona in 1956, veteran umpire Jocko Conlan, a former major-league outfielder, offered some advice: “If a pitcher misses [with] the first pitch when you’re hitting, look for a fastball on the second pitch.” White recalled, “And that’s the way I hit for fourteen years.”6 He was playing for the Triple-A farm club at Minneapolis when the Giants called him up in May. In his first time at bat, in St. Louis on May 7, he slammed a home run off right-hander Ben Flowers. He added a single and a double later in the game, but went 1-for-16 before he hit his second home run, off Don Newcombe six days later. He homered twice off Robin Roberts on the last day of the season to bring his total to 22, with a .780 on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS).

That bought White a ticket to the Army. His draft notice spurred the Giants to trade for Jackie Robinson to play first base, but Robinson retired. Before White was inducted, he married his high-school sweetheart, Mildred Hightower, on November 20, 1956. They would have five children before they divorced in the 1980s.

The Army assigned White to the supply room at Fort Knox, Kentucky. He played for the post baseball team until he was refused service in a restaurant. Most of his white teammates went on with their meal and White, angry at their indifference, quit the team at the end of the season. He supplemented his Army pay by playing semipro ball for $50 a game.

When White rejoined the Giants in July 1958, the team had moved to San Francisco and he had lost his job. Orlando Cepeda was playing first base, becoming a favorite of Bay Area fans on his way to the Rookie of the Year award. The Giants had another first baseman, 20-year-old Willie McCovey, in Triple-A. Newspapers immediately began speculating that White was trade bait. The next spring manager Bill Rigney said he would keep White as a pinch-hitter and occasional first baseman when Cepeda would move to third. White wanted no part of that; he told a reporter, “You can’t make the big money unless you’re a top-ranking major-league regular.”7 On March 25, 1959, the Giants traded him to St. Louis with third baseman Ray Jablonski for pitchers Don Choate and Sam Jones, the latter a three-time National League strikeout leader.

White had wanted to be traded, but not to St. Louis. The Cardinals had three first basemen, all left-handed: Joe Cunningham, George Crowe, and Stan Musial, who was moving to first to rest his 38-year-old legs. Besides, black players did not feel welcome in St. Louis; the Cardinals were the last major-league team to integrate seating at their ballpark. Looking back, White said, “Eventually it would turn out to be one of the best moves of my life.”8 He played primarily in the outfield in 1959, and acknowledged that he was terrible at it, but he batted over .350 for most of the first half. Players and managers elected him to his first All-Star team as a left fielder. He tailed off to finish at .302 with an .814 OPS. The next year White spent most of his time at first base, winning the first of seven Gold Gloves, and by 1961 he was the Cardinals’ everyday first baseman.

Fourteen years after Jackie Robinson’s debut, baseball’s spring-training sites in Florida were still segregated in 1961. In St. Petersburg the Cardinals’ black players stayed with local families. The pioneering black sportswriter Wendell Smith had raised the issue and a few major newspapers took up the story. That spring the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce invited only white players to its annual “Salute to Baseball” breakfast. White complained to a reporter, “When will we be made to feel like humans?”9 He was one of the few black players—if not the only one—to speak up publicly.

A St. Louis-area newspaper called for a black boycott of Cardinals owner August A. Busch, Jr.’s beer. Busch was no liberal, but he was a dedicated capitalist. He ordered his staff to make the problem go away. By the next spring a St. Petersburg businessman had bought two motels and made them available to the team. Stars including Musial and Ken Boyer, who usually stayed with their families in rented beach houses, moved into the motels in a show of solidarity. Several players manned grills at dinnertime and White’s wife, Mildred, conducted classes for the children. Locals would drive by to watch black and white families frolicking together in the pool, a sight unprecedented in the Deep South.

In 1962 White began a five-year run as one of the NL’s elite players. He posted an adjusted OPS (OPS adjusted for park and league average) above 120 every year (100 is defined as the league average) while winning Gold Gloves. In ’62 his .868 OPS and .324 batting average were career bests. The next year he registered career highs with 200 hits, 106 runs, 27 home runs, and 109 RBIs. Along with Julian Javier, Dick Groat, and Ken Boyer, White was part of the all-Cardinal starting infield in the 1963 All-Star Game. (He also won the Cardinals’ horseshoe-pitching tournament.) The team won 19 of 20 games to close within one game of the first-place Dodgers in September, and finished second.

In pursuit of “the National League pennant nobody seemed to want,”10 White, like several of his teammates, stumbled through the early months of 1964, then came on strong in the second half. After the All-Star break he raised his batting average from .263 to .303 and his OPS from .704 to .829. In the season’s final game, when the Cardinals had to win or go home, White singled in the fifth inning and scored the go-ahead run, then added a two-run homer in the sixth as the Cardinals beat the Mets to clinch the pennant. He finished third in the Most Valuable Player voting, behind teammate Boyer and Philadelphia’s Johnny Callison. White said the 1964 Cardinals were a close-knit team: “There’s no way to quantify the spirit that a group of men share, but in baseball, as in the military, that spirit can sometimes make the difference between victory and defeat.”11

White batted only .111 in the World Series, but he contributed two hits and scored a run in the Game Seven victory over the Yankees. That night he showed up to speak at a St. Louis church banquet, as he had promised months before when the Cardinals appeared to be out of the pennant race. After fulfilling his commitment, he joined his teammates at Stan Musial’s restaurant for a celebration.

After St. Louis fell to seventh place in 1965, general manager Bob Howsam traded three-fourths of his pennant-winning infield: White, Boyer, and Groat, the only players in the lineup over 30 years old. White, not yet 32, was the youngest of them, but Howsam told reporters he thought the first baseman was actually older. (There is no evidence that he was.)

White and Groat went to the Phillies with backup catcher Bob Uecker for pitcher Art Mahaffey, catcher Pat Corrales, and outfielder Alex Johnson. White did not like his new manager, Gene Mauch: “He was a control freak. The way to win is to let players play.”12 He didn’t care for the tough Philadelphia fans, either, but he bought a house and made the area his permanent home.

White gave the Phillies a standout performance in 1966, with 22 home runs and 103 RBIs, but he went into a sudden decline after he tore his right Achilles tendon while playing paddleball. In 1967 he was able to start only 90 games as his batting average fell to .250. He said the Philadelphia trainers would shoot him up with Novocain, in addition to dispensing amphetamines. His average dropped to .239 in 1968 and he was traded back to St. Louis, where he wound up his career in 1969 primarily as a pinch-hitter. “I gave it 16 years of my life and never less than 100 percent on the field,” he said. “So we’re even.”13 Later he wrote, “I didn’t love baseball. Because I knew that baseball would never love me back.”14 The Cardinals offered White a Triple-A managing job, but he had already chosen his next career.

When White chided Harry Caray about how easy his broadcasting job was, Caray invited him to try it. While playing for the Cardinals he worked part-time for KMOX radio in St. Louis. In Philadelphia he hosted a pregame radio show and worked in the offseasons as a sports reporter on local television. One of his early assignments was a hockey game; inevitably, he referred to the puck as the ball. After retiring, he became a full-time sports anchor for WFIL-TV and studied with a New York voice coach to improve his performance.

White had met Howard Cosell before the sportscaster became famous and respected him for his coverage of racial issues. Cosell recommended him to the Yankees for their play-by-play job. In 1971 he became the first African American broadcaster for a major-league team—although, despite his radio and TV experience, he had never called a baseball game. The plan was to let White start as a color analyst and break him in slowly on play-by-play. But as he broadcast his first spring-training game with Phil Rizzuto, the Scooter spotted Joe DiMaggio in the stands and bolted out of the booth to greet his old teammate, leaving White on his own. White survived to start a rewarding partnership with Rizzuto.

The former shortstop was a famously casual broadcaster, plugging his favorite restaurants, especially those that supplied free cannoli, and leaving games in the seventh inning so he could beat the traffic home to New Jersey. It was said that the most frequent entry in his scorebook was “WW,” for “wasn’t watching.” White blossomed as his on-air foil and straight man. Rizzuto always called him “White,” never “Bill.” They worked side by side for 18 seasons and became friends. When Rizzuto was dying in 2007, White visited him in the hospital and silently held his hand. White said, “I loved Phil Rizzuto.”15

White said Yankees owner George Steinbrenner twice offered him the job of general manager, but he knew better than to work directly for “The Boss.” In 1989 the 55-year-old White had decided to leave the Yankees. He had earned enough respect in broadcasting circles to call several World Series for the CBS Radio Network, but the Yankees had switched most of their games to cable, leaving only about 60 each season for White on WPIX-TV. He thought it was a good time to retire.

Los Angeles Dodgers president Peter O’Malley invited White to interview for the job of National League president, but he said he was not interested. O’Malley called again and White agreed to talk to the search committee. He understood what was going on; less than two years earlier, Dodgers general manager Al Campanis had ignited a firestorm when he said blacks might lack “the necessities” to be managers or general managers. Baseball had a public-relations problem, one that only a high-profile African American could fix. White later acknowledged, “Let’s face it, they wanted a black National League president.”16 Token or not, “Bill had no choice but to accept that job,” his friend Bob Gibson said. “Not for himself, but for other people.”17

In addition to being the first black league president, White was the first former player to head the National League since John Tener 70 years earlier. (Former shortstop Joe Cronin had served as president of the American League.) The president’s duties included supervising the umpires and disciplining players. White also had to deal with Marge Schott, the Cincinnati Reds owner whose drunken rants and racist comments repeatedly embarrassed baseball. White said she never showed her racist side to him; in fact, she thanked him for treating her more respectfully than her fellow owners did.

White and Richie Phillips, the leader of the umpires union, despised each other. Phillips said White still thought like a player and took their side against the umps.18 Not all players agreed. White suspended Cincinnati pitcher Rob Dibble twice in one season. When the Phillies’ John Kruk was named to the 1991 NL All-Star team, he remarked, “That’s the first time I got a letter from Bill White where I didn’t have to pay a fine.”19

White believed his most important accomplishment as league president was helping to guide the expansion that awarded teams to Denver and Miami. Even that came with controversy. The American League owners demanded a share of the entry fees paid by the new teams, and Commissioner Fay Vincent sided with them, although the AL had not shared its windfall when it expanded in 1977. White protested that Vincent was butting in on a National League matter. He also accused Vincent of interfering on disciplinary issues that were the league president’s prerogative.

Before the expansion cities were chosen, White thought he had exacted a promise from the new Colorado Rockies that they would interview minorities for front-office jobs. When they didn’t, he said he was “surprised and disappointed” that the team had broken its word. This time Vincent joined in the criticism of the Rockies’ owners.20

White had made his living by talking, but his major shortcoming as president, his critics said, was his silence. He seldom went to ballgames and refused most interviews. He did not speak out on his passionate conviction that baseball needed to integrate the ranks of managers and executives. “It’s the same for all of us in positions we’ve achieved,” said Frank Robinson, then one of two black managers in the majors. “If we don’t speak up and speak out, who will?”21 White contended he could best serve the cause of equal rights by doing his job well, but he admitted that minorities in baseball made little progress during his tenure.

White shed his reserve in a 1992 speech to the Black Coaches Association—preaching to the choir before a nonbaseball audience. He said he was bitter about the racism he faced in his job, adding, “I deal with people now who I know are racists and bigots.”22 He praised Commissioner Vincent for hiring minority executives in Major League Baseball’s central office, but he and Vincent could not persuade teams to integrate their front offices.

Despite his differences with the commissioner, White thought the owners destroyed the independence of the commissioner’s office when they forced Vincent out in 1992. With Milwaukee owner Bud Selig installed as acting commissioner, White said, “No longer was there even the pretense that an objective ‘outside baseball’ authority was watching over the best interests of the game.”23 He soon realized that Selig intended to concentrate power in his own hands and abolish the position of league president. White retired in 1994. When the owners wanted to give him a farewell dinner, he told his successor, Leonard Coleman, “You can tell the owners I said the hell with them.” He believed the owners “understood the business of baseball. But I don’t think they ever truly understood the game.” 24

White filled his retirement with fishing and trips in his motor home, accompanied by the woman he called his “lady friend,” Nancy McKee. He guarded his privacy until the 2011 publication of his autobiography. He titled it Uppity. “I use ‘uppity’ as a point of pride,” he said. “I demanded to be recognized for what I accomplished, nothing more. If people thought that was uppity—and many did—so be it.”25

Last revised: January 28, 2022 (zp)

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 “All Things Considered,” NPR, May 11, 2011

2 Bill White, with Gordon Dillow, Uppity: My Untold Story About the Games People Play (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2011), 7

3 Ibid., 29

4 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 161

5 White, Uppity, 38

6 Moffi and Kronstadt, 160

7 United Press International, Chicago Defender, March 21, 1959, 23

8 White, Uppity, 60

9 Ibid., 73

10 Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1964, D1

11 White, Uppity, 90

12 Philly Post, April 21, 2011. http://blogs.phillymag.com/the_philly_post/2011/04/21/the-former-phillie-everyone-should-know/, accessed September 30, 2011

13 Stan Hochman, “Bill White Keeps His Promises,” Baseball Digest, January 1969, 39

14 White, Uppity, 47

15 Ibid., 147

16 Claire Smith, “Baseball’s Angry Man,” New York Times Magazine, October 13, 1991, 53

17 Ibid., 56

18 Ibid., 31

19 “They Said It,” Sports Illustrated, July 15, 1991, online archive

20 New York Times, September 28, 1991, 1

21 Smith, “Baseball’s Angry Man,” 30

22 “NL Prexy Bill White Cites Baseball Racism,” Jet, June 15, 1992, 46

23 White, Uppity, 282-283

24 Ibid., 7

25 Philly Post, op. cit.

Full Name

William DeKova White

Born

January 28, 1934 at Lakewood, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.