Baseball Before a Captive Audience: The Minnesota State Prison’s Sisal Sox, 1914-72

This article was written by Rich Arpi

This article was published in Fall 2017 Baseball Research Journal

One aspect of amateur baseball that is largely unexplored is the baseball played in our nation’s prisons. Prison games are easily overlooked by historians because few in the general public witnessed these games and they are seldom documented. One exception is the Stillwater State Prison in Stillwater, Minnesota, whose prison newspaper—The Prison Mirror, managed and edited by the prisoners—documented nearly 1,300 games between the prison team and outside opponents between 1914 and 1972. Most of these games were played against amateur teams from Minneapolis, St. Paul, and neighboring towns in Minnesota and Wisconsin, but as the years wore on, high school and American Legion teams peppered the schedule, as did an occasional appearance by the professional St. Paul Saints and Minneapolis Millers of the American Association.

The first territorial prison was awarded to Stillwater in February 1851 by the Minnesota Territorial Legislature, which simultaneously awarded the capitol to St. Paul and the University of Minnesota to St. Anthony.1 At the time, it was uncertain whether any of the three cities had a compelling case for hosting any of the institutions, all three being small frontier towns. Nonetheless, Stillwater was thrilled to get the prison.

Stillwater, about fifteen miles east of St. Paul, is situated on the St. Croix River, which forms the boundary between Wisconsin and Minnesota. Stillwater is often referred to as the birthplace of Minnesota, because it was the site of the territorial convention of 1848, which paved the way to territorial status a year later. The town was incorporated on March 4, 1854 (the same day as St. Paul), and much of its early history was dominated by the lumber industry. Several lumber mills cut millions of board feet of lumber per year there for decades. Even so, the city never grew very large; the 1900 census figure of 12,818 was the highest population until 1990 when the figure reached 13,882. The prison was coveted since it would add jobs to the local economy in security, food preparation, and administration.

Construction on the prison commenced in the spring of 1851, carved into the limestone hills just north of downtown and a stone’s throw from the St. Croix. The prison was completed in 1853 and began taking prisoners. A house for the warden and his family was also completed in 1853 on a ledge of the hill overlooking the prison.

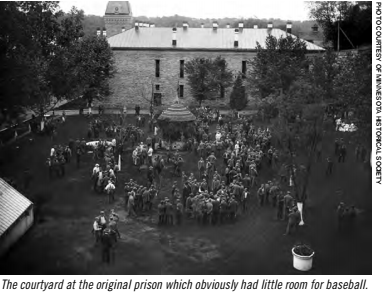

When Minnesota became a state in 1858, the Stillwater prison became the Minnesota State Prison, and as the years passed, buildings were added and the capacity expanded. But the prison was hemmed in by the hillside, which formed a natural barrier, and the few acres east of the prison that led down to the St. Croix River were owned by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad. In 1890 a twine factory, which relied exclusively on prison labor, was built inside the prison walls. Quickly the prison became crowded, with the prisoner’s cells small, cold, and damp. Ventilation was poor and cockroaches and bedbugs were everywhere. The prison courtyard was a small space that had no room for recreation other than a few yards for walking.

Need for a new prison was recognized as early as the 1880s, but it was not until just before World War I that a new prison was built and ready for use. The new facility was built three miles south, on the flat plain above the river bluffs in Bayport. The first prisoners were transferred to the new prison in January 1909. However, population at the new facility remained at 60–70 prisoners for the next four years. Possibly these men helped to build the prison, but more likely they were employed by a department of a valuable prison industry whose new facilities were ready for use. The new prison population did not exceed 200 individuals (only about one-fifth of the total prison population) until December 1912. Most of the prisoners were transferred in 1913 and the early months of 1914. By early summer of 1914 the entire population of around 1,000 men and about a dozen women had been transferred. While the new buildings were close to one another, as in any other prison, room was left for a ball field in the north part of the complex. Warden Henry Wolfer granted some new rules and privileges, which included:

- Inmates will be permitted to talk to those sitting beside them at Sunday dinner.

- Music will be furnished by the Prison Orchestra during the noon meal every Sunday.

- Two picture shows will be given in the auditorium each week—on Tuesday and Friday afternoons.

- Baseball and athletic events will be played on the prison Green every Saturday afternoon.2

Henry Wolfer, a trained penologist, started his career at the Joliet state prison in Illinois in the 1870s before coming to Stillwater in the mid-1880s as deputy warden. On June 7, 1892, Wolfer became warden at the Stillwater State Prison, and except for a 15-month period in 1899-1901, he held that post through October 1914. Wolfer continuously advocated for reforms that would make prison life more civilized and would provide opportunities for inmates to have a chance in the outside world upon release.

The prisoners wasted little time implementing the new rules, as the prisoner newspaper reported in the next issue, “The crack of the bat as it struck the ball; the yell of the umpire and the enthusiastic cheers and yells of the fans, was heard for the first time within prison walls in Stillwater last Saturday when over six hundred delighted inmates of the new prison gathered on the prison green to enjoy the new rules recently announced by Warden Wolfer. It was a grand sight, one never to be forgotten by those beholding it. Men who have been prisoners here for long terms—some of them who have seen thirty and thirty-five years of penal servitude, could not repress the tears that coursed over their cheeks; and all they could say as they went about clasping the hands of their fellows, was ‘Aint it grand –oughtn’t we be thankful.’”3

While the guards had occasionally played baseball with other teams from outside the prison walls beginning in 1908, allowing the prisoners to play baseball was a new privilege, as was permission to be outside in open air for any extended period of time. The prisoners quickly divided themselves into teams. One team represented the prison newspaper employees and another the band and orchestra members. Another team, The Green Sox, soon became the dominant prison team, and by September challenges went out to outside teams. Local clubs from Stillwater who faced the Green Sox included the Starkels, a team of bakery employees, and Simonet’s, a furniture and carpet company. Clubs from as far away as LeSueur and Hinckley, Minnesota, came in for games. The season, which ended in November, left the prison team with a 3-6 record against outside clubs.4

A successful 1914 season laid the groundwork for the baseball program at the prison to continue. The biennial reports of the warden from 1916 through the late 1940s provide snippets of information on the baseball program, usually only a few sentences, but illuminating nonetheless. Warden J.J. Sullivan, in the 1923–24 report, writes, “During the baseball season the score and standings of the major league clubs is posted daily on the large scoreboard in the dining room. The men are appreciative and it is no question but that these weekly diversions have a tendency toward good conduct.”5 Warden after warden repeated the thought that baseball improved morale and conduct because only those prisoners who were in good standing could participate on the teams or watch the games, which were held between three and six o’clock on Saturday afternoons and on holidays.

Dorothy and Harold Seymour in their book, Baseball: The People’s Game, devote the following paragraph to baseball at the Stillwater prison:

Baseball became incorporated into the unwritten by-laws at the Stillwater, Minnesota, State Penitentiary with the appointment of Charles S. Reed as warden in October 1914. Although inmates had played one or two games before his arrival, Reed encouraged the baseball spirit supposedly “inherent in every man”. He put up a huge scoreboard at the front of the dining hall, where everyone could see it. Each day before the noon meal he had the scores of all major-league and double-A minor league games posted. The men received permission to converse at the table every other day, and comments on the deeds of Cobb, Speaker, Johnson and other stars filled the air. In an even more radical move, Reed continued the pay of Stillwater men working in the prison industries when the shops shut down for the ball games. Although this policy cost the prison an estimated $1,200 per game, or from $5,000 to $6,000 a month, Reed believed the money well forfeited. “We try not to forget,” he said, “that the purpose of the industries is not to make goods and revenue for the state, but to make better men of the inmates, while at the same time protecting society.” Inmates at Stillwater fielded both a first and second team, and the prison’s weekly newspaper published accounts of games, played every Saturday afternoon and on holidays, and attended by all inmates except those deprived of the privilege for misconduct. High walls and buildings bound the field, and balls hit over them were lost. Although four iron lamp posts stood in the outfield no accidents ever occurred. An outsider, usually a Stillwater citizen, umpired games. All costs of uniforms and equipment came from a quarter admission fee charged visitors.6

The monetary amounts stated by the Seymours in the above paragraph may overstate the financial loss somewhat. Prison industries probably worked at least a half day on Saturday and possibly up to a half hour before game time, and since most industries during this time worked a five-and-one-half-day week, the prison industries were not at a competitive disadvantage. Also the twine factory had a virtual monopoly, since there wasn’t a private firm locally that provided this product needed by farmers of the upper Midwest. The prisoners, like other private industries, wouldn’t have worked on holidays, either. Continuing the nitpick: probably just the American Association, the league of the nearby St. Paul Saints and Minneapolis Millers, and the American and National League scores were posted; balls hit over the fence or on the roofs of buildings could easily be retrieved; and evidence of an active second nine that played outside teams regularly does not exist, although there were plenty of players ready to step in and play the prison nine when a visiting team cancelled at the last minute.

Although the prison ball team was mentioned occasionally in the Stillwater Gazette, the town’s daily newspaper, and the St. Paul Pioneer Press, comprehensive coverage of each game was recorded in the Prison Mirror. Established in 1887, the Prison Mirror is the oldest continuously published prison newspaper in the country. It was published weekly on Thursdays between 1887 and 1955, biweekly between 1956 and August 1993, and monthly September 1993 to date. While prison newspapers are not unusual, significant runs of prison newspapers have not been widely archived, cataloged, and made available, but the Mirror is an exception and is available on microfilm at the Minnesota Historical Society. Managed and edited by the prisoners, its masthead stated, “It aims to be a home newspaper; to encourage moral and intellectual improvement among the prisoners; to acquaint the public with the true status of the prisoner; to disseminate penological information and to aid in dispelling that prejudice which has ever been the bar sinister to a fallen man’s self redemption.”7

Prisoners received copies delivered to their cells and were expected to place it at the foot of the bed the next morning for disposal. Each prisoner was also allowed to send one copy home to family members or to a friend for free. The paper was not shy in critical commentary or analysis of each ballplayer’s performance on the field. Weekly columns, bearing bylines of “Bobbles,” “Diamond Dust,” or “A Fan,” on events in the major leagues and the American Association were as detailed and informative as any newspaper, including the daily St. Paul Pioneer Press or Minneapolis Tribune. Rosters of the Federal League teams were provided, as were news of player transactions. In the days before photographs became commonplace in newspapers, humorous artwork peppered the game accounts.

While the 1914 prison team was known as the Green Sox, that name quickly faded, and for the next twenty years the prison team was known as the Greys, the Stars, or just the Minnesota State Prison (MSP). In 1936, the prison officials decided to hold a contest among the prisoners to come up with a new name for the team that had more color and meaning. Hundreds of suggestions poured in, and among the names considered were these: Hermits, Spinners, Minnesota Binders, Rebels, Interstate Comets, Fagans, Walled City Gophers, Racqueteers, Sinners, and Jaybirds. Names of birds, beasts, and insects were also popular as were names of such natural disasters as hurricanes and cyclones. Several entrants adorned their entries with clever drawings, and one entry was a poem indicating the valor and ability of the local nine. Officials set up a convoluted voting procedure to weed the suggestions down to a popular few. The name Sisal Sox was chosen, in nod to the twine factory which used sisal as a raw product. Sisal Sox became the name of Stillwater prison’s all-star team that played outside teams and pickup prison teams until its demise after the 1972 season.8 For the rest of this article, I will refer to the Stillwater prison team as the Sisal Sox, even if years prior to 1936 are under discussion.

Between 1914 and 1972, the Sisal Sox played 25 to 30 games per year, and results of nearly 1,300 games against outside opponents are recorded in the Prison Mirror. Playing as an independent club for most of their history, the Sisal Sox compiled a 689–546–43 record against outside clubs. For a few years in the late 1950s and 1960s, the Sisal Sox were a member of the Friendly Valley League, and played a 14-game league schedule in addition to numerous non-league games. The most common opponents were the Bayport—or South Stillwater—town team and the Stillwater town team, the prison’s closest neighbors. The Sisal Sox compiled a record of 66 wins, 60 losses, and one tie between 1915 and 1954 against the Bayport-South Stillwater team and a record of 31–17–2 between 1931 and 1947 against Stillwater, with a 7–10–1 record against the Stillwater Loggers between 1948 and 1960.

Other local opponents were Oak Park 1915–19 (9–2) and the Omaha Railroad Shops from Hudson, Wisconsin, 1921–41 (25–19–1). Common St. Paul opponents were the St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Company team 1922–37 (5–7), the Knights of Columbus (15–3) 1923–29 and the Lorence Recreation Club 1946–58 (5–10). Frequent Minneapolis opponents were the American Linen Supply Company 1916–59 (24–23–2) and the West End Athletic Club 1926–35 (14–8). The most common college opponent was the River Falls, Wisconsin, Teachers College, who faced the Sisal Sox 1915–52 (9–12–2 record for the Sox).

When an outside team would cancel, the Sisal Sox would play a prison all-star team. Their record between 1915 and 1966 against the “second string” team was a stellar 19–1–2, implying the Sisal Sox truly did recruit the best baseball talent in the prison.9

Among the managers who brought teams to the prison, Bill “Sully” Sullivan is notable. He managed the American Linen team and numerous all-star teams from Minneapolis from 1922 through 1972. Umpires were often prison guards or officials, but quite often mayors and businessmen of neighboring Stillwater and Bayport performed yeoman service. The field at the Minnesota State Prison at Stillwater was dedicated as Swanson Memorial Field on August 17, 1957, in memory of Roy G. “Swanny” Swanson, a man who had devoted twenty years to scheduling baseball, football, basketball, and softball games at the prison as well as taking his turn as the plate umpire every Saturday. Sisal Sox center fielder Jim “Nellie” Nelson, when asked about the dedication said, “I think it is a heck of a good idea. I know of no one else who has worked as hard to bring sports to this institution, and certainly no one ever donated as much time to the athletic program as Swanny did.”10

At least one Hall of Famer played against the Sisal Sox at the Minnesota State Prison. Bud Grant, a 1994 inductee to the Professional Football Hall of Fame, played against the Sisal Sox in 1954 and 1955. Grant, a nine-time letterman in football, basketball, and baseball at the University of Minnesota, is best known for spending ten years as head coach for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers of the Canadian Football League, and 18 as the head of the Minnesota Vikings. In the summers of 1950, 1951, and 1952, Grant played for the Osceola, Wisconsin, semi-pro baseball club and in 1954 and 1955 for the Stillwater Loggers. Grant was absent during the September games between the Sisal Sox and Osceola, being otherwise occupied at football training camp, but was able to play for the Loggers against the Sisal Sox in June and July. In the 1954 game Grant played in left field and in 1955 he pitched for a few innings and added a home run.11 Minneapolis Laker greats Vern Mikkelsen (now there is a big strike zone) and Whitey Skoog, were on the Excelsior, Minnesota, club roster for a 1955 game but did not play at the prison, much to the disappointment of the prisoners.

The Sisal Sox were not shy about scheduling tough opponents; at least eight opponents were or became state amateur champions, including the St. Paul Armours, sponsored by the Armour meat packing company (state champions in 1924 and 1926). The Sisal Sox played the Armours seven times between 1925 and 1929 (1–5–1 record for the Sox). Other champions included the St. Paul Milk Company (1932 champions), J.J. Kohn of St. Paul (1935), The Commission Row officers of Fort Snelling (1936), Northern States Envelope (1938), Soderville (1951–52), Bloomington (1965), and Columbia Heights (1967–68). While the Sisal Sox’s record against these top amateur clubs was not good, the Sox were competitive and the prisoners enjoyed watching good quality baseball. The J.J. Kohn team of St. Paul that they played six times between 1938 and 1944 (1–6–1 record for the Sox) had won the national amateur tournament in Battle Creek, Michigan, in September 1937.

Special treats were five games between the Sisal Sox and the top professional teams in the area, the Minneapolis Millers and St. Paul Saints of the American Association. The Millers beat the Sox on October 28, 1916, 10–7. The Millers out-hit the Sisal Sox 18 to 14 with Dave Altizer and George Capron of the Millers each collecting four hits.12

The first game against the St. Paul Saints was played on October 18, 1924, an 8–2 win for the Saints that featured four hits by Bruno Haas, including a home run and a triple.13 The St. Paul American Association champions had just defeated the Baltimore Orioles five games to four in the Junior World Series and were on their way to the West Coast to play a series with the PCL champion Seattle Indians. Other Sisal Sox–St. Paul Saints games were played on July 1, 1940, August 29, 1941, and September 4, 1942. The Saints won all three games, 15–5, 10–5, and 7–2. The 1940 game featured 17 strikeouts by Saints reserve pitcher Howie Belknap.14

The 1941 game was interrupted by a torrential rain, and the Saints were good sports by waiting the rain out and playing ten innings to boot rather than cancel and go home. The regulars—as announced by the WTCN radio voice of the Saints, George Higgins—were replaced after play resumed, and several players took their shirts and shoes off and had a jolly good time sliding in the mud, much to the amusement of the crowd.15

The 1942 game featured Saints pitcher George “Slick” Coffman clowning around while umpiring the bases, and he also took a turn on the clarinet with the prison band.16 Another professional game was a July 26, 1944, game between the Saints and Millers, or more accurately the reserves of the Millers and Saints played at the prison, a game won by Minneapolis, 9–4.17

The Sisal Sox actually played several road games in their history. The first game was a local game with the Stillwater Interstate League club on April 27, 1918. Between 1938 and 1942 the Sisal Sox played a series of twenty games against the prison team of the St. Cloud Reformatory in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Their team was known as the Red Tops and at least three games were played in St. Cloud: September 17, 1938, and June 28 and July 26, 1941, with the Red Tops winning two of the three games. Overall, the Sisal Sox won 16 of the 20 games played, and the series was discontinued after several years. In 1960, when the Sisal Sox were members of the Friendly Valley League, at least one playoff game was played outside the prison walls.

Road games were infrequent not because prison officials had serious issues with them. The security and logistics were not insurmountable; after all, prisoners were transported all the time. The overarching reason was that the baseball game on Saturday and holiday afternoons became part of the routine of prison life. Most of the prisoners looked forward to the games, and attendance figures, when given, were usually over 95% of the prison population and occasionally topped 1,000 individuals. Bleacher seating was limited so many prisoners stood three or four deep behind the plate and down the foul lines. Jack Junker, who played for the Stillwater Loggers against the Sisal Sox in the 1950s, recalls the prisoners betting cigarettes on the outcome of at-bats (hit or not) and prisoners rooted avidly for the other team.18 While much of the cheering was probably good-natured razzing, there is a possibility some of the men really didn’t like each other and were openly rooting for the visitors.

Dave Junker, who played football and softball against prison teams in the 1970s and 1980s (thus missing the Sisal Sox) recalls the experience all visiting teams went through between 1914 and today. In addition to being searched upon entering and leaving the prison, visitors’ hands were stamped with invisible ink as a precaution against prisoners trying to sneak out with the visiting team. Teams would have to march through the cell block to the field, a requirement that might have unnerved more than one young player. Dave recalls the baseball field being ringed by a running track and weight lifting stations, with some prisoners otherwise occupied during the game. Afterwards, the visiting teams were fed a meal with the prisoners in the mess hall. Fresh vegetables from the nearby prison farm were plentiful.19

For many years, baseball was the only sport mentioned in the Prison Mirror, but other sports and diversions eventually were added. Kittenball, or softball, was first mentioned in the 1929–30 biennial report of the Warden, but it would take thirty years or so before interest in the Sisal Sox was eclipsed by softball and other sports. Horseshoes were mentioned in the 1933–34 biennial report and again in the 1951–52 report. The early 1940s saw the staging of several boxing matches and wrestling bouts at the prison. Radio broadcasts of University of Minnesota Golden Gopher football games began in 1937 and amazed several lifers who had no idea what a radio was. The prison football team, the Colts, began in the late 1950s. Unlike the prison football team in the Burt Reynolds-Eddie Albert film “The Longest Yard,” they did not play the guards but outside teams. While films were mentioned in the Mirror as a weekly activity as early as 1908, the 1933–34 biennial report added that the films were censored and that “no crime or gangster pictures are permitted.” Some lifers thus were culturally deprived in not being exposed to the talents of one Edward G. Robinson.

Using box scores and game accounts from the Prison Mirror 1914–72, I have attempted to compile an all-time roster for the Sisal Sox. This work is made more difficult by the fact that nicknames or abbreviations of names are used and that nicknames, being rather fluid, change from year to year, depending on the correspondent. Roy Austin was referred to as “Speedy” in some reports and “Rabbit” in others. Freckles, Schnozz, and Bobby Brown all played for the Sox at the same time in the 1950s and are easily confused for one another and possibly with several other Browns without listed monikers. Other nicknames listed were Robert “Moose” Morris, John “Water Buffalo” Northrup, “Yogi” Zelmer, Mel “Linus” Waltz, and Ernie “The Monster” Verdick.

The Stillwater prison’s most infamous residents were Jim, Cole, and Bob Younger, who were incarcerated on November 18, 1876, for their participation with Jesse James in the Northfield, Minnesota, bank raid on September 7, 1876. During this bank robbery—which has spawned numerous books and a number of movies and has passed into folklore—four people were killed. Bank clerk Joseph Lee Heywood, citizen Nicholas Gustavson, and raiders Clell Miller and William Chadwell lost their lives. Cole, Jim, and Bob Younger were captured several days later in Madelia, Minnesota, after an approximately four-hundred-mile chase. Jesse James eluded capture for a few years before being shot in 1882. Bob Younger died in prison in 1889 and Jim and Cole Younger were paroled in 1901, well before sports became a fixture at the prison. While I haven’t found any inmate with major league experience, either previous to or after their sentences at Stillwater, I will not be surprised if further research will uncover a few individuals with some minor league experience. Many of the Sisal Sox played at least some amateur ball before finding themselves behind bars, some playing high school or college ball only a few years before. Whatever the situation, I feel it is important to acknowledge the ball players at the Stillwater State Prison with an all-time roster that is as accurate as possible.20

The Sisal Sox baseball club ceased after the 1972 season after playing only a handful of games over the preceding three years. Possibly one of the reasons for the decline of the Sisal Sox was that over time more and more of the prison population became involved in intramural teams in basketball, broom hockey, softball, and volleyball. Most prisoners would rather play on their own team rather than watch the Sisal Sox. It became more difficult to schedule games for the Sisal Sox as amateur baseball declined in the 1960s. More and more high school teams filled the schedule in the 1960s compared to earlier eras. The constant turnover of prisoners—some dying, some being released, and some just getting old—was a factor in the team’s decline as was the prison’s all-star softball team, which was more competitive, taking players and interest away from the Sisal Sox. Possibly not having a take-charge guy like Roy Swanson leading the way could have been another factor. Even though the crack of the bat is no longer heard at the Stillwater prison, it is undeniable that baseball was the sport that led the way to a full athletic program and a dramatic change in prison life, especially when compared with the conditions at the original prison. ◊

RICH ARPI is a reference librarian and archival cataloger for the Ramsey County Historical Society in St. Paul, Minnesota. He has been a SABR member since 1982 and is an active member in Minnesota’s Halsey Hall Chapter giving numerous presentations on Minnesota baseball history over the years. He has previously written two BioProject biographies and two articles for The National Pastime in 2012.

Sources

Numerous sources can be found at the Minnesota Historical Society, including the following.:

Bartlett, G.L. Thru the Mill by “4242”: A Prison Story that’s Different. St. Paul: McGill-Warner Company, 1915. Reprinted by the Washington County Historical Society, 2016.

Dunn, James Taylor. “The Minnesota State Prison During the Stillwater Era, 1853–1914.” Minnesota History. December 1960. 137–51.

Genoways, Ted, editor. Hard Time: Voices from a State Prison, 1849–1914. Foreword by Ted Conover. Introduction by James Taylor Dunn. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

History of the Warden’s House Museum. Stillwater, Minnesota: Washington County Historical Society, 2017.

Notes

- Minneapolis, on the west side of the Mississippi River across from St. Anthony, was not incorporated until 1867. The two cities merged in 1872 and today the name St. Anthony is used only by locals to designate a neighborhood on the east side of the Mississippi River.

- The Prison Mirror, Thursday, June 4, 1914. Microfilm copies of the Stillwater prison newspaper are located at the Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota.

- The Prison Mirror, June 11, 1914.

- Most of the buildings at the original prison were demolished in 1936. One factory building existed until 2002 when it was destroyed in a fire. Condominiums now occupy the old prison site. The Warden’s House, built in 1853, is the only original building at the old prison site still intact. It is operated as a museum by the Washington County Historical Society.

- Biennial Report of the Stillwater State Prison, 1923–1924. Located at the Minnesota Historical Society.

- Dorothy Seymour Mills and Harold Seymour, Baseball: The People’s Game (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 404.

- The Prison Mirror, November 1914.

- The Prison Mirror, May 21, 1936.

- Spreadsheet compiled by the author, entitled SisalSoxOverall, listing games won and years played against each opponent and yearly records as compiled from game accounts in the Prison Mirror.

- The Prison Mirror, August 9, 1957.

- The Prison Mirror, November 2, 1916.

- The Prison Mirror, June 23 and July 7, 1956.

- The Prison Mirror, October 23, 1924.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 2, 1940.

- The Prison Mirror, September 4, 1941

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 5, 1942.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 27, 1944.

- Jack Junker, telephone interview, November 10, 2016.

- Dave Junker, telephone interview, November 9, 2016.

- Excel spreadsheet, Sisal Sox Roster, compiled by the author from box scores and game accounts from the Prison Mirror.