Catcher Duke Farrell’s Record Performance: Game Notes from May 11, 1897

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

Duke Farrell as depicted with the Chicago White Stockings on an Old Judge baseball card, circa 1888–90. (Trading Card Database)

Welcome to nineteenth-century baseball research, where it is not uncommon for the newspapers to have conflicting box score data, and for the box score data to be in conflict with the written article covering the game, or the scoring data included with the box score to be in conflict with the data in the box score itself. This makes researching nineteenth century baseball challenging, but also very rewarding once all the pieces are put together in an accurate manner.

The Baltimore Orioles and the Washington Senators played quite an interesting, record-setting game on Ladies Day, May 11, 1897, in Washington. The record books indicate that catcher Charles A. “Duke” Farrell established a record for throwing out the most base-stealers in a single game: eight. For example:

- 1898 Reach Guide under Some Playing Features: Catcher Farrell, of the Washingtons, threw out eight of the Baltimores at second base on May 11th.1

- 1924 Little Red Book under Catchers’ Fielding Records, National League: Most runners thrown out in attempts to steal base, game 8— C.A. Farrell, Wash. (vs Balto.)…May 11, 1897 2

- 1928 Little Red Book under Catchers’ Fielding Records: Most runners thrown out in attempts to steal base, game—8 Charles A. Farrell, Washington NL, vs Baltimore, May 11, 1897 3

- 1963 One for the Book under Catchers’ Fielding Records: Most Men Caught Stealing, Game, Nine Innings N. L.—8—Charles A. Farrell, Washington, May 11, 1897 4

- 1982 Edition of The Book of Baseball Records under Base Runners Caught Stealing: Most Base Runners Caught Stealing, Game 8 Charles A. Farrell, NL: Wash. May 11, 1897 5

While the published box scores support that Farrell had eight assists in the May 11 game, what is not supported is how the assists were acquired. The record books state that all eight of Farrell’s assists were the result of throwing out baserunners attempting to steal. The 1898 Reach Guide goes so far as to claim that all eight were thrown out at second base. But I was familiar with this game from previous research and upon seeing the record books I questioned, “Was it eight?” I reviewed my game file: Two newspapers stated that Farrell threw out only six baserunners, not eight. The discrepancy spurred me to dig deeper into the facts of the game.

I started with the game account in the Baltimore American (the primary source for the 1897 Baltimore Orioles box scores I generated for previous research). The American reported, “One of the features of the game was the daring base running of the Baltimores. It was daring, but unsuccessful, because of Charlie Farrell, who is supposed to have a lame throwing wing. Every attempt to get to second—and there were six attempts—resulted fatally to the Baltimore sprinters.”6

The Washington Post account was similar: “The features of the games [sic] were the pitching of Brother Joe Corbett and the backstopping of Duke Farrell. Farrell built a record for himself that probably will stand as one of the remarkable events of the major League season. He is credited with eight assists, six of which were on throws that nailed the Orioles in their attempts at stealing bases. Stenzel, the Orioles’ winged-foot champion, got gay on two occasions and was thrown out by Farrel [sic]. McGraw, Keeler, Kelly [sic] and O’Brien were also caught in the act of kleptomania by the Duke’s emotional and shifty wing.”7

However, the following list of the players that Farrell threw out makes three things clear:

a) Only six, not eight, baserunners were thrown out in an attempt to steal.

b) Not all of the six were thrown out at second base.

c) John McGraw was not one of them.

Runners Caught on May 11, 1897

- Jake Stenzel, second base, first inning

- Joe Kelley, second base, third inning

- Jake Stenzel, second base, fourth inning

- Heinie Reitz, second base, fourth inning

- Willie Keeler, caught off base after safely reaching third, fifth inning

- Tom O’Brien, second base, eighth inning

The Baltimore Sun chalked up some of the outs on the basepaths as follows:

Four different times men on first base started to steal, expecting the batter to hit with the runner, and were caught, simply because the batters stood like wooden men and made no effort to hit the ball. This occurred three times in the third and fourth innings alone. In the third Kelley was caught because Doyle did not hit the ball, although it was called a strike. In the next inning Stenzel, who had singled, was caught because Reitz gave him no help, and Reitz was treated the same way by Clarke. Clarke was excusable, however, as the ball was over his head. O’Brien was caught in the eighth in the same way by Stenzel’s not hitting.8

The Keeler play at third base, however, was reported by the Washington Post thus:

Duke Farrell’s arm came into play in the fifth. McGraw lined one too tall for O’Brien, the ball tipping Johnnie’s mitt. Mugsy [McGraw] was forced on Keeler’s roller to DeMontreville. Jennings hit to short left field, and Selbach made a strong bid for Hughey’s liner, but it fell at Sel’s feet, Keeler reaching third. Jennings started for second on a steal, and the Duke made a feint to throw to O’Brien, but shifted and caught Keeler off third.9

The Baltimore Sun described Keeler’s resulting outburst: “Hurst called Keeler out on third base once, and so surprised and angry did that usually quiet player become that he ran at Hurst like a cyclone.”10 Technically the Keeler out at third was a pick off, not a caught stealing, thus only five of the six Farrell throw-outs were to catch a player in the act of trying to steal a base.

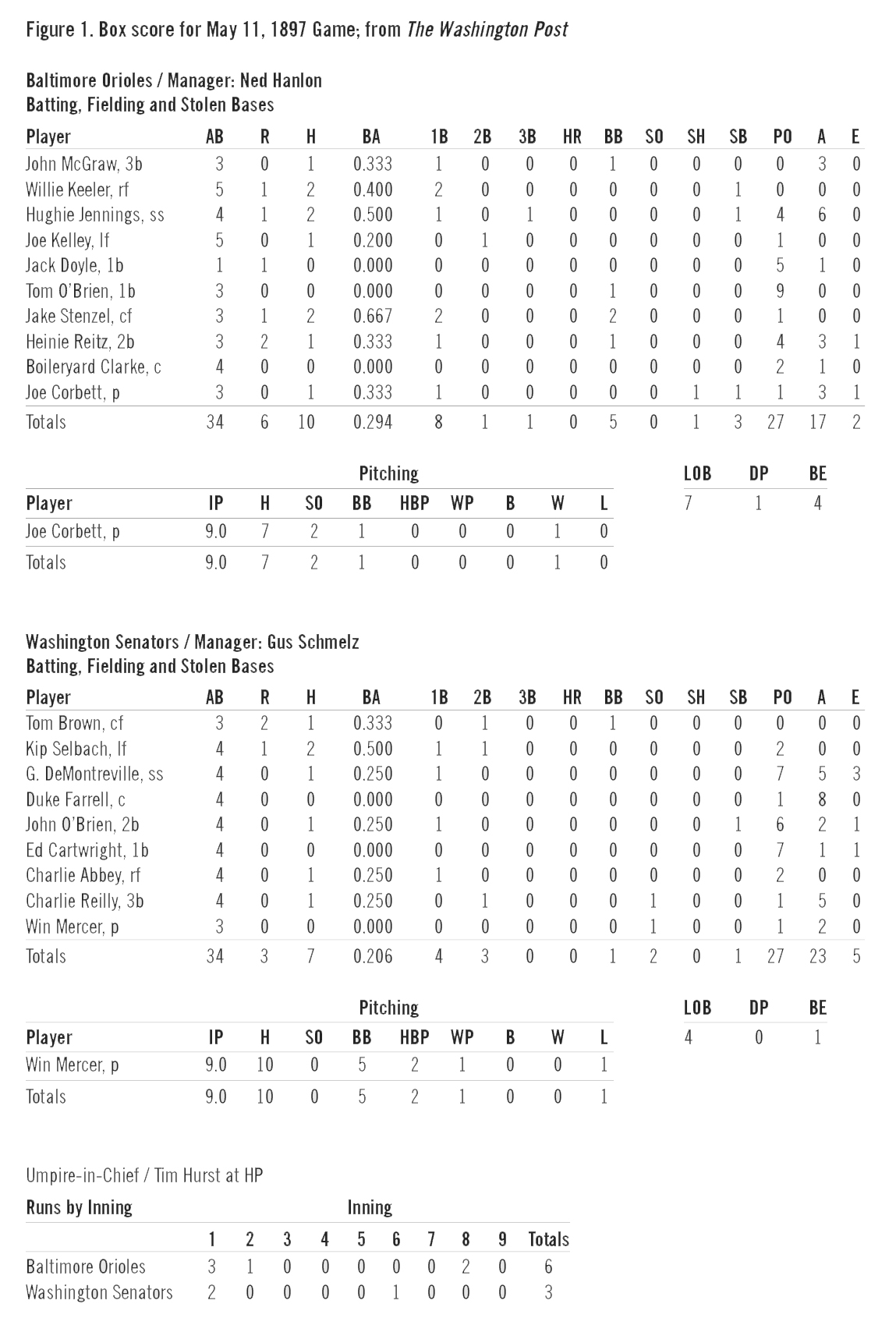

According to the game box score (see Figure 1) Duke Farrell had one put out, eight assists, and zero errors. Baltimore’s Joe Kelley was caught in a rundown between third and home in the first inning. Kelley was tagged out by DeMontreville, but presumably Farrell assisted on the play which would account for the seventh assist. The second inning saw Joe Corbett sacrifice and presumably Farrell assisted on the out for the eighth assist. The second inning also featured a put out at home plate when Boileryard Clarke was called out. Presumably the put out was by Farrell.

Interestingly, the Baltimore Orioles’ players did manage to steal some bases despite Farrell’s efforts, the number of which varies depending on which newspaper you read. The Washington Post lists three stolen bases (by Keeler, Jennings, and Corbett). The Baltimore American listed only Corbett as having stolen a base while the Baltimore Sun credited the Orioles with five stolen bases: two by Keeler and one each for Jennings, Stenzel, and Corbett. Given that the game was played in Washington, it isn’t surprising that The Washington Post provided the most thorough overall account of the game. Their total of three stolen bases was likely the most accurate:

- Willie Keeler stole second base, second inning

- Hughie Jennings stole second base, fifth inning

- Joe Corbett stole second base, eighth inning

In addition to the eight Farrell assists, the game featured two other noteworthy incidents, both involving Jack Doyle, the Baltimore first baseman.

The first was reported by the Washington Post:

Keeler, the infant phenom., went to Baltimore last night, plus an addition to his lip and minus one molar. His troubles came off in the second, when Ed. Cartwright shoved a fly into short right field that the omnipresent Queensberry gentleman, Jack Doyle, bucked up for. While Jack was rearing Keeler advanced on a canter, and ran into Jack’s elbow, which landed on his wind. Jack’s head collided with one of Keeler’s molars, a dental mishap that deprived him of an ivory. But Keeler pocketed the molar and betook himself to his reservation, whereat the crowd warmed to him and gave him a glad-hand serenade.11

The Baltimore American’s version of the collision:

Before his expulsion Jack came very near putting Willie Keeler out of the game for a long time to come. Doyle is an ambitious player, who takes every chance that offers to win a game. A short fly went up to right field, and Doyle and Keeler both went for it. The ball was in Keeler’s territory, but Jack, without warning, pursued the ball, and the result was a violent collision with Keeler. Keeler was momentarily stunned by the shock, and for a few minutes lay motionless upon the grass. It was at first thought that he was seriously injured, for both players were running at full speed when they came together.

The players gathered around him and he was deluged with water, and finally recovered and resumed his place in the field.12

The Baltimore Sun printed the following:

Keeler came near being badly hurt in the second inning by a collision with Doyle. Doyle ran out into right field after Cartwright’s fly, which was Keeler’s ball, and the collision knocked Keeler down and out for a few minutes. He recovered and continued to play.13

The second incident involved Doyle being ejected from the game. As the Washington Post colorfully reported:

Physician McJames, however, diagnosed a speech that Jack Doyle made at the home plate, and pronounced Jack’s English as suffering from a compound fracture. Jack’s sprained English was passed at Umpire Hurst because Tim called a strike on Jack, who had $25 worth of conversation with Tim, and was finally ordered to beat an exit from the grounds. O’Brien, the Orioles’ substitute outfielder, replaced Jack at first.

After his exit Doyle returned and fanned baseball with a cluster of railbirds perched on the Freedmen’s Hospital fence in deep left field.14

From the Baltimore American:

There was enough scrapping by the players and kicking against the umpire to please the most exacting lover of excitement. Jack Doyle figured in animated debate with Tim Hurst, and the result was that Jack was not only banished from the game, but he was ordered out of the grounds, with a heavy fine chalked up against him.

Tim Hurst could not have inflicted severer punishment upon Doyle than by putting him out of the game.15

And the Baltimore Sun:

In the third inning Doyle was put out of the game and out of the grounds because of his objection to a strike being called on him. Up to that time Hurst had been doing fairly well, and the strike called on Doyle was certainly not a flagrant error, if an error at all, but from that time forward Hurst gave everything against the visitors.

He “roasted” Corbett on balls and strikes until the usually placid Clarke, after protesting mildly time and again, finally got so exasperated that he came near being expelled from the game.16

A further point of note involved the Baltimore players being hit by pitched balls, as the Baltimore American stated, “Several of the Baltimore players were hit by pitched balls but in every instance the blow was intentional. The crafty Orioles picked out Mercer’s slow balls and placed their bodies near enough to the plate to come in contact with the horsehide and be rewarded by a free pass to first.”17 Although the Orioles did their best to be credited with many HBP, only two were actually awarded, McGraw and Jennings, both in the seventh inning which led to a bases-loaded situation but no runs. The Washington Post added, “Then Mercer jolted McGraw over the kidneys with an inshoot, Mugsy reaching third on Keeler’s single to center. Jennings was hit by Mercer and was forced on Kelly’s [sic] grounder to DeMontreville, O’Brien covering the base with neatness and dispatch.”18

The newspaper box scores don’t agree on the number of hits (H) or at bats (AB), either. The Baltimore American lists eight hits for the Orioles, while the Washington Post lists 10 and the Baltimore Sun 12. The discrepancy undoubtedly has to do with which errors were deemed to have occurred. The individual ABs in the Baltimore American box score didn’t make sense from a plate appearance point of view. John McGraw, who played third base and batted first for the Baltimore Orioles, was listed as having four AB, one base on balls (BB) and one hit by pitch (HBP): six plate appearances. Four batting order positions after McGraw was the combination of Jack Doyle and Tom O’Brien (O’Brien replaced Doyle in the third). Doyle had one AB, O’Brien had three, totaling four—but O’Brien also had a BB which meant a total of five plate appearances. No problem there except for the fact the preceding batting order position—Joe Kelley, who batted fourth—only had four plate appearances.

To further muddy the waters, the seventh and eighth batters—Heinie Reitz and Boileryard Clarke respectively—only had four plate appearances each, but Joe Corbett, batting ninth, had five: four AB plus one sacrifice hit. How can a later batting order position have more plate appearances than an earlier position? It’s impossible.

The Washington Post box score (see Figure 1 on page 106), on the other hand, made much more sense: The BB, HBP, and the SH add up properly relative to the ABs. All 42 plate appearances—five for the first six positions in the batting order, four for the latter three—can be validated by summing the AB (34), BB (5), SH (1) and HBP (2).

Another conundrum was served up by the Baltimore American. They stated that Washington’s DeMontreville and Selbach had sacrificed, DeMontreville in the first inning and Selbach in the sixth. None of the box scores listed either of them with a sacrifice hit, including the Baltimore American itself. This non-listing makes sense from a plate appearances point of view given that each player was credited with four AB, zero BB, and zero HBP. The American likely labeled the DeMontreville and Selbach efforts improperly.

Any time a researcher finds him or herself in a situation where research identifies an error in the historical record, the first reaction is that “I must have made a mistake” and/or “I must have missed something.”19 Review of what we know about the game on May 11, 1897, though, it’s clear that the record books are wrong. Duke Farrell did in fact have eight assists in the game against the Baltimore Orioles—but only five of the assists, not eight, were catching runners stealing second base. Since the stated references do not categorically detail his involvement, the remaining three assists must be presumed to involve the pick-off at third, the rundown between third and home, and the put out of a batter who sacrificed. This researcher is aware of at least two other nineteenth century catchers who threw out five at second base in a single game: 1) Charlie Bennett on July 22, 1881 and 2) Tom Daly on July 5, 1887. I will leave the readers with this final note about Duke Farrell and his skill at throwing to second base: “Charley Farrell is working a very clever trick this season. In practice before the game the Duke makes a bad mess of getting the ball down to second, but after the game starts the fast base runner discovers that Farrell is throwing true to the mark.”20

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada, and a longtime researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football and MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them, and two books in his 60 years with two baseball books on the way — one on the 1927 New York Yankees and the other on the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian has been a SABR member since 2013 and is a longtime member of the PFRA. Growing up Brian played many sports including football, rugby, hockey, baseball along with participating in power lifting and arm wrestling events, and aspired to be a professional football player but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons in the “front row.”

(Click image to enlarge.)

Notes

1. A.J. Reach. Reach’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1898. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: A.J. Reach Co., 1898. Reprinted in 1990 by Horton Publishing Company.

2. John B. Foster, Editor (Compiled by Charles D. White). Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, part of the Spalding “Red Cover” Series of Athletic Handbooks, No. 59R. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1924.

3. John B. Foster, Editor (Compiled by Charles D. White). The Little Red Book: Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, part of the Spalding’s Athletic Library, No. 59B. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1928.

4. Leonard Gettelson, Preparer. One for the Book for 1963: Complete All-Time Major League Records. St. Louis, MO: Charles C. Spink & Son (The Sporting News), 1963.

5. Seymour Siwoff, Editor. The Book of Baseball Records. New York, New York: Seymour Siwoff , 1982.

6. “A BATTLE OF PITCHERS: In Which Joe Corbett is Ahead of Mercer,” Baltimore American, Wednesday, May 12, 1897, page unknown.

7. “MERCER THEIR CINCH: Has Never Pitched a Winning Game Against the Orioles,” Washington Post, Wednesday, May 12, 1897, 8.

8. “HARD TIME WITH HURST!: Corbett Saves the Game,” Baltimore Sun, Wednesday Morning, May 12, 1897, 6.

9. Washington Post, op. cit.

10. Baltimore Sun, op. cit.

11. Washington Post, op. cit.

12. Baltimore American, op. cit.

13. Baltimore Sun, op. cit.

14. Washington Post, op. cit.

15. Baltimore American, op. cit.

16. Baltimore Sun, op. cit.

17. Baltimore American, op. cit.

18. Washington Post, op. cit.

19. This is true not only in baseball research and records. I recall having those exact thoughts at the time I discovered that Jim Brown, the famous running back for the NFL Cleveland Browns, had actually gained over 1000 yards rushing—1016 to be exact—in the 1962 season rather than the 996 yards he was credited with. See Brian Marshall. “Rushing to Judgment: Recovering Jim Brown’s Lost Yardage from 1962.” The Coffin Corner, Volume 35, Number 3, May/June 2013, 9–12.

20. “Baseball Notes,” Baltimore Sun, Friday Morning, May 21, 1897, 6.