The Enigma of Hilda Chester

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

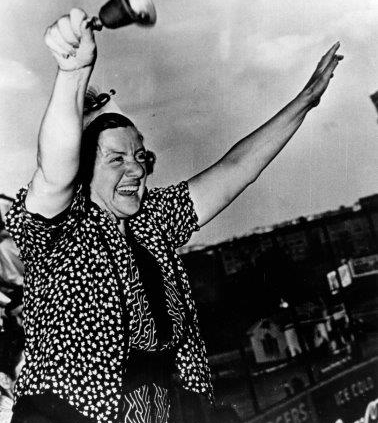

Hilda Chester and her famous cowbell (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The New York Yankees have their Bleacher Creatures. The crosstown Mets had Karl “Sign Man of Shea” Ehrhardt, while “Megaphone Lolly” Hopkins was the super-fan of the Boston Red Sox and Braves. Cleveland Indians, Chicago Cubs, Detroit Tigers, and Baltimore Orioles rooters have respectively included John “The Drummer” Adams, Ronnie “Woo Woo” Wickers, Patsy “The Human Earache” O’Toole, and “Wild Bill” Hagy. Then there are the Brooklyn Dodgers, whose off-the-field attractions included their Sym-Phony, Eddie Bottan and his police whistle—and Hilda Chester and her cowbell.

Hilda, otherwise known as “Howlin’ Hilda,” was a product of the outer-borough “woiking” classes: a dees-dem-dose, toidy-toid-‘n’-toid Brooklynite. Granted, when interviewed, she was capable of using the King’s English. More often, however, her responses were pure Brooklynese. She criticized one-and-all by pronouncing, “Eatcha heart out, ya bum,” and identified herself by declaring, “You know me. Hilda wit da bell. Ain’t it t’rillin’?” And she is as much a part of Dodgers lore as Uncle Robbie and Jackie Robinson, Pistol Pete, Pee Wee, and “Wait ‘til next year.” “I absolutely positively remember Hilda Chester because I often sat near her in the Ebbets Field bleachers,” recalled Murray Polner, the author of Branch Rickey: A Biography. “Brooklyn Dodger fans all recognized her cowbell and booming voice.” (Polner added: “There was another uber-fan who would scream, ‘Cookeee’—for Lavagetto.”)1

Hilda’s reputation even transcends the Borough of Churches. Bums author Peter Golenbock labeled this “plump, pink-faced woman with a mop of stringy gray hair” the “most famous of the Dodger fans—perhaps the most famous fan in baseball history,”2 while Bill Gallo of the New York Daily News called her “the most loyal and greatest fan to pass through the turnstiles of the Flatbush ballpark.”3 The Los Angeles Times cited her as “perhaps the greatest heckler of all time” who would “scream like a fishmonger at players and managers, or lead fans in snake dances through the aisles.”4 Seventy years earlier, The Sporting News had christened her “the undisputed Queen of the Bleachers, the Spirit of Brooklyn, the Bell of Ebbets Field, and we do mean Bell.”5

Despite these accolades, little is known about Hilda Chester outside of baseball—and this was her preference. While piecing together the facts of her life, it becomes apparent that she was the product of a hardscrabble youth and young adulthood, one that she steadfastly refused to acknowledge. Writer Thomas Oliphant, whose parents got to know Hilda in the Brooklyn ball yard, described her background as “truly the stuff of legend, much of it unverifiable…. My father…told me that behind her raucous behavior was a tough, often sad life, but that she was warm and decent under a very gruff exterior.”6 What is certain, however, is that whatever joy Hilda took from life came from her obsessive love of sports—and especially her devotion to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

So little is known about Hilda that the place of her birth cannot be confirmed. According to the United States Social Security Death Index, she was born on September 1, 1897.7 No location is listed; most sources cite her birthplace as Brooklyn, but this may be conjecture given her identity as a Dodgers fanatic. More than likely, Hilda was born and raised on the East Side of Manhattan, but no one knows the identities of her parents or the circumstances under which she settled in Brooklyn.8 In fact, in 1945 Hilda was queried as to what brought her to Brooklyn. “I liked da climate!” was her sarcastic response.9

What is certain is that Hilda was a product of urban poverty. “Home was never like this…,” she noted in a 1943 interview in The Sporting News. “I haven’t had a happy life. The Dodgers have been the one bright spot. I do not think I would want to go on without them.” The article observed, “Nothing Hilda does startles [the Brooklyn players] any more. She is one of the family.” Tellingly, the paper also reported, “Any further efforts to inquire into Hilda’s early history meet a polite ‘Skip it!’ And when Hilda says ‘Skip it,’ she means it.”10

Reportedly, Hilda played ball in her youth. “As a young girl she was willing to sock any boy who wouldn’t let her play on the baseball teams…,” noted journalist Margaret Case Harriman.11 For a while, she was an outfielder for the New York Bloomer Girls and she hoped to one day either make the majors or establish a women’s softball league. But this was not to be, and so she transformed herself into a rabid Brooklyn Dodgers booster. The story goes that, when Hilda was still in her teens, she would hang around the offices of the Brooklyn Chronicle in order to be the first to learn of the Dodgers’ on-field fate.

Various sources note that Hilda was married at one time but that her husband had passed away. A daughter, Beatrice, was a product of their union, and the child also had baseball in her blood. As “Bea Chester,” she played briefly in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. In 1943 she was with the South Bend Blue Sox, where she was the backup third baseman, appearing in 18 games and hitting .190. The following season she joined the Rockford Peaches, where she made it into 11 games. Her batting average in 42 at bats was .214.12

While playing for the Blue Sox, recalled Lucella MacLean Ross, “I had two different roommates. One was Betty McFadden, and the other was Bea Chester. She’s a lady they have never traced as an All-American girl. Her mother was quite famous.… they used to call her ‘Hilda the Bell-Ringer.’ Her name was Hilda Chester.”13

After the 1945 campaign, Bea “retired” as a professional ballplayer. In 1948 columnist Dan Parker reported that Hilda “is a grandma now and has decided to bring up young Stephen as a jockey instead of a Dodger shortstop.”14

The AAGPBL website features a photo of Bea but also reports, “This player has not been located. We have no additional information.” However, the young woman in the picture bears a marked resemblance to the photo of a Beatrice Chester that appears in the June 1939 yearbook of Thomas Jefferson High School, located in the East New York section of Brooklyn. Are the two one and the same? It certainly seems so. For one thing, this Beatrice Chester is cited as her school’s “Class Athlete.” She is dubbed “the ‘he-man’ of girls’ sports” who “bowls, plays ping pong…She possesses letters in tennis, volley ball, basketball, baseball, hockey, shuffleboard, deck tennis, badminton…she has won a trophy at Manhattan Beach for the hundred yard dash, the running broad jump, and in baseball and basketball throw.”15 (In 1945, Hilda admitted to Margaret Case Harriman that Beatrice was a “very good soft-ball player.” Harriman asked her where her daughter played. Hilda did not cite the AAGPBL. Instead, she “hastily” responded, “Oh, up at that school she don’t go to no more.”16)

Most telling of all, the Jefferson yearbook notes, “To relieve the monotony of winning awards, Beatrice plays the mandolin and banjo.” On two occasions, a younger musically-inclined Beatrice Chester was cited in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reportage of events sponsored by the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum. In February 1932, the paper covered “an afternoon entertainment staged by the boys and girls who live in the institution.” One was Beatrice Chester, who performed a mandolin solo.17 Then in December 1933, at an event sponsored by the asylum’s women’s auxiliary, Beatrice “played several selections on a mandolin…”18

What emerges here is that Hilda and Beatrice were Jewish, and Beatrice was a “half-orphan:” a child with one parent, but that parent was incapable of looking after her. Observed Montrose Morris, a historian of Brooklyn neighborhoods, “By 1933, during the Great Depression, the [asylum] estimated that 65% of their children had parents, but the parents were too poor to take care of them.”19

Given her lack of finances, one cannot begin to calculate how many Dodgers games Hilda saw during this period, nor can it be determined exactly when she became an Ebbets Field habitué. The Sporting News reported that she began regularly attending games “when a doctor told her to get out in the sunshine and exercise an arm affected by rheumatism.”20 It was not until the late 1930s, however, that Hilda was a conspicuous Ebbets Field presence. That was when Larry MacPhail, the Dodgers’ new president and general manager, inaugurated Ladies’ Day in the ballyard; one afternoon each week, for the price of a dime, women could file into the bleachers. “The price was right,” Hilda recalled years later. “I used to come to the park every Ladies’ Day. I was like any other ordinary fan. Then I started to get bored…,” and this resulted in her transformation from one of the anonymous masses into a uniquely colorful Dodgers devotee.21

Additionally, Hilda had long been unable to secure steady employment. But then the Harry M. Stevens concessionaire hired her to bag peanuts before sporting events; her job was to remove the peanuts from their 50-pound sacks and place them into the smaller bags that would be sold to fans. When she wasn’t redistributing peanuts, she could be found selling hot dogs for Stevens at New York-area racetracks, a job she kept for decades. And she relished her employment. “They’re all so good to Hilda,” she observed. “When you got no mother, no father, it’s nice to have a boss that treats you nice.”22

On game days in Brooklyn, Hilda would grab a spot at the Dodgers players’ entrance and greet them upon their arrival. She then would make her way to her seat in the center field bleachers where she loudly yelled at the players, her booming voice echoing throughout the stadium. After the game, she would situate herself along the runway beneath the stands that led to the team’s locker room and either applaud or console her boys, depending upon the final score.

Her employment with Stevens aside, sportswriters began providing Hilda with passes, which further enabled her to mark her Ebbets Field turf. Initially, she preferred the cheap seats to the grandstand. “What, go down there and sit with the shareholders?” she once quipped, “And leave these fine friends up here…. All my friends (are) here. They all know me! They save my seat for me while I am checking the boys in every day. Leave them? Never.”23 She added, “There are the real fans. Y’can bang the bell all y’darn please. The 55-centers don’t fuss so much about a little noise.”24

Hilda was not exclusively a baseball devotee. During the offseason, she made her way to Madison Square Garden to root for the New York Rangers, and she exhibited the same hardnosed devotion to the hockey team as she displayed in Brooklyn. On February 27, 1943, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle printed the following Hilda query: “Just a few lines to let you know I couldn’t wait for today’s Eagle to see what kind of writeup you gave the Rangers last night after that game with Detroit. I think it’s a rotten shame the way those referees treat our Rangers. I thought it was only in baseball they play dirty. Now I think it’s worse in hockey. How come?”25 Nonetheless, Ebbets Field and its environs were her preferred home-away-from-home. Hilda and her daughter were occasionally observed knocking down pins at Freddie Fitzsimmons’s bowling alley, located on Empire Boulevard across the street from the field.26

Various stories chart the manner in which Hilda expanded her repertoire from voice to cowbell. The most commonly reported is directly related to a heart attack she suffered in the 1930s. Her doctor eventually ordered her to cease bellowing at ballplayers, which led to her banging a frying pan with an iron ladle. They were replaced by a brass cowbell, which reportedly was a gift from the Dodgers’ players in the late 1930s. She also was noted for waving a homemade placard for one and all to see. On it was an inscription: “Hilda Is Here.”

After suffering a second heart attack in August 1941, Hilda found herself confined to Brooklyn’s Jewish Hospital. “The bleacher fans have taken on a subdued atmosphere since the absence of the bell-ringing Hilda,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “but she sends them all her best regards and urges them ‘to keep their thumbs up and chins out and we’ll clean up the league’.” While being prepared for a medical procedure, Hilda pinned a Dodgers emblem to her hospital gown and asked if she could hold onto a Brooklyn Daily Eagle clipping of Dixie Walker and Pete Reiser.27 Her health status was covered in the media, with the paper running a photo of a smiling Hilda, holding what presumably was the Walker-Reiser clipping, above the following caption: “Howlin’ Hilda Misses Dodgers: From a bed in Jewish Hospital Hilda Chester, popular bell-ringing bleacherite, roots for her faithful Dodgers to bring home the bacon.”28

After being bedridden for two weeks, Hilda announced that she was planning to leave the hospital and make her way to Ebbets Field for a game against the rival New York Giants. “I will be calm,” she told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “Oh, yes. I have to be calm. But—sure, I’ll take my bell along, just for luck. And will I ring it when our boys show them Giants how to play ball? Sure, I will, just for luck. And, oh yes, I guess I’ll cheer a little, too, for Leo [Durocher] and Dixie [Walker] and the rest of the boys.”29 So against doctors’ orders, Hilda returned to Ebbets Field because, as she explained, her boys “needed me.”30

While hospitalized, Hilda had been visited by no less a personage than Durocher, who then was the Bums’ skipper. It was for good reason, then, that Durocher was a Hilda favorite. After the 1942 season, scuttlebutt had it that the Dodgers were about to fire Leo the Lip. “[W]hat’s all this noise going on about not re-signing Leo Durocher N.L. best Mgr., again in 1943,” Hilda wrote the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “You know, I know that we all know whom we have but who knows what we will get. For the past two seasons Leo did a wonderful job and for that reason must the Dodgers get a new Mgr.” The missive was signed “HILDA CHESTER, 100% real loyal Dodger bleacher rooter.” Her mailing address was 20 DeKalb Avenue in downtown Brooklyn.31

During the 1945 campaign, The Lip faced a felonious assault charge for allegedly donning brass knuckles and helping to beat up John Christian, a medically-discharged veteran. Hilda immediately came to Leo’s defense. “The pernt is this: Christian had been pickin’ on nearly all the Dodger players for more’n a month—with a verce like a foghorn,” she declared. “He shouldn’t been usin’ langwidge that shocked the ladies.”32 In court, Hilda was called to the witness stand and promptly perjured herself, claiming that Christian had called her a “cocksucker”—and the manager merely was defending her honor.

By this time, Hilda occasionally accompanied the team on short road trips; “I’m travelin’ right along in da train wit da boys,” she declared in 1945. “Ain’t it t’rillin’?”33 During the war years, she also appeared at the team’s temporary spring training site at Bear Mountain in upstate New York. “Close to 500 watched the Dodgers in action on the Sabbath,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle during spring training in 1943. “A sizeable delegation of Brooklyn fans were headed by Milton Berle, the comic, and Hilda Chester, the cowbell girl.”34

Hilda was by then a semi-celebrity who was synonymous with the Dodgers brand, and who was cited in the same sentence as big-name entertainers. New York Post columnist Jerry Mitchell dubbed her “the Scarlett O’Hara of Ebbets Field,” and her name even occasionally appeared in game coverage.35 “Whether it was Durocher, Charley Dressen, Johnny Corriden or Hilda Chester, someone was responsible for a lot of wild masterminding in a wild and at times fantastic game,” wrote The New York Times Louis Effrat, reporting on the Dodgers’ tenth-inning victory over the Boston Braves in August 1944.36

And certainly, Hilda reveled in her fame. “I notice in [your] Sunday magazine section you gave me a little plug,” she wrote Times columnist Arthur Daley. After thanking him, she added, “For heaven’s sake, don’t call me a character.” She signed the missive “Hilda Chester, The Famous One.”37

It was around this time that Hilda went Hollywood. Whistling in Brooklyn (1943), an MGM comedy, stars Red Skelton as “The Fox,” a popular radio sleuth who is a prime suspect in a series of murders. He is chased into Brooklyn and winds up at Ebbets Field, where the Dodgers are playing an exhibition with the Battling Beavers, a House of David-style nine. “The Fox” dons a fake beard and impersonates “Gumbatz,” the Beavers’ starting pitcher, in a sequence that features such real-life Dodgers as Leo Durocher, Billy Herman, Arky Vaughan, Ducky Medwick, and Dolph Camilli.

As Herman comes up to bat, a female fan is shown on-camera and yells out what is best translated as: “Will ya get it wound up son of a seven, you Gumbatz.” Could it be? Yes, it’s none other than Hilda Chester. (“Beware, Hollywood!” observed columnist Alice Hughes in the Reading Daily Eagle. “Hilda Chester, most famous rooter of our beloved Brooklyn Dodgers, has been playing a bit in [the] Red Skelton movie, ‘Whistling in Brooklyn,’ some of it filmed in the Dodgers’ ball park—so look out Hedy Lamarr and Greer Garson!”)38

Additionally, Brooklyn, I Love You (1946), a Paramount Pictures short highlighting the Dodgers’ 1946 season, features such Brooklyn stalwarts as Durocher, Pee Wee Reese, Pete Reiser, Eddie Stanky, Red Barber—and Hilda. A Hilda-ish fan, played by character actress Phyllis Kennedy, appears in several scenes in The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), the first “42” biopic; the Hilda-inspired Sadie Sutton, a gong-beating fan, is one of the minor characters in The Natural, Bernard Malamud’s 1952 novel. Around this time, Hilda began popping up on radio and TV shows. For example, on April 19, 1950, she guested on a This Is Your Life radio tribute to umpire Beans Reardon. Among those appearing on the July 23, 1956, edition of Tonight!, with Morey Amsterdam substituting for host Steve Allen, were “Diahann Carroll, vocalist,” “Oscar Peterson, jazz pianist,” and “Hilda Chester, Dodger fan.” Then on March 7, 1957, Hilda guested on Mike Wallace’s Night Beat interview program. Her fellow interviewee was Gerald M. Loeb, a founding partner of E.F. Hutton & Co.

Across the years, Hilda formed warm personal relationships with players. In 1943, The Sporting News reported that “Brooklyn’s No. 1 rooter…always remembers the Dodgers’ birthday with cards, visits them in hospitals when they’re ill or injured and consoles them in their defeats.”39 Noted Dixie Walker: “She never forgets a birthday. She sends us the nicest cards you ever saw, on all important occasions. I think she’s wonderful.”40 Hilda the super-fan even had kind words for Dodgers’ management. Of Branch Rickey, she observed: “Anything the boss does, he knows what he’s doin’.” But clearly, Leo the Lip was her favorite. “They don’t come any better in my book,” she declared.41

On one occasion, in a well-reported anecdote, Hilda actually affected the outcome of a game. Whitlow Wyatt was the Dodgers’ starting pitcher. It was the top of the seventh inning; the year was either 1941 or 1942. The story goes that, as center fielder Pete Reiser took his place in the field, Hilda handed him a note and instructed him to deliver it to Leo Durocher. Upon returning to the bench, Reiser gave it to his manager—and Durocher assumed that the missive was from Larry MacPhail. It read: “Get [Dodgers reliever Hugh] Casey hot. Wyatt’s losing it.” Upon taking the hill, Wyatt surrendered a hit and Durocher promptly replaced him with Casey, who almost lost the game. An irate Durocher berated Reiser for handing him the note without explaining that it was from Hilda rather than MacPhail.

(As the years passed, different versions of the story were cited. For example, as early as 1943, The Sporting News reported that Hilda had written: “Better get somebody warmed up, Casey is losing his stuff out there.”42 In a 1953 Brooklyn Daily Eagle column, Tommy Holmes—after observing that “in 1941, [Hilda] was the unchallenged dream boat of the cheap seats”—recalled that she had written: “[Luke] Hamlin seems to be losing his stuff—better get Casey warmed up.”43 Then in 1956, Reiser claimed that the Dodgers’ starting pitcher that day was Curt Davis, rather than Wyatt.44 But the essence of the tale remains unchanged.)

During the 1943 campaign, after the Dodgers dropped their ninth game in a row, Tommy Holmes observed, “When nobody else loves the Dodgers, Hilda Chester will…”45 Perhaps Holmes was a bit optimistic. Just before the 1947 season, Hilda abruptly switched her allegiance to the New York Yankees. It was noted in The Sporting News that her “feelings have been hurt by certain persons in the [Dodgers] business office. It seems Hilda wrote in for her customary seat, but got a bill for $24.50, instead. She angrily denied the presence of Laraine Day [the Hollywood actress who was Durocher’s wife at the time] had anything to do with it. ‘Laraine?’ she said. ‘That’s Leo’s headache’.”46 Queried Brooklyn Daily Eagle columnist George Currie, “[W]hat is Ebbets Field ever going to be again, without her cowbell?”47

But Hilda never could become a true-blue American League devotee. Later that season, she and her “Hilda Is Here” banner began inhabiting the Polo Grounds; by the following year, the New York Giants had become her team of choice, in part because she claimed to have had difficulty obtaining 1947 World Series tickets, but also because, midway through the campaign, her favorite baseball personality left his Ebbets Field managerial post for the vacated one in Coogan’s Bluff. The Sporting News published a photo of Hilda and an unidentified female fan holding a large sign with “Leo Durocher” on it. In responding to a question about her health, Hilda explained, “I hardly ever get pains now, except for what they done to my Leo.”48

A statue of Hilda Chester now stands in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

All was soon forgiven, however, and Hilda returned to her outfield perch at Ebbets Field. In fact, she was presented with a lifetime pass to the Flatbush grandstand; eventually, in a departure from her loyalty to the center-field denizens, she was given a reserved seat near the visitors’ dugout. In 1950 she was asked if she ever received free Ebbets tickets. “Free tickets!” she bellowed. “I never accepted free tickets. They always give me complementaries.”49

The cowbell was not the only gift to Hilda from her Brooklyn “boys.” In August 1943 she was presented with a silver bracelet that featured her first name across the band and a small baseball dangling from the chain. “Was Hilda the happiest woman in Brooklyn last night?” queried The New York Times. “Silly question!”50 In August 1949, the Dodgers awarded her a charm bracelet for her “loyalty” as the team’s number one fan. On Mother’s Day 1953, after she dyed her hair “a flaming red,” team owner Walter O’Malley—in a pleasant mood because the Dodgers were completing a winning home stand and had just bested the Philadelphia Phillies—had a florist deliver to her a large bouquet with a note inscribed, “To Brooklyn’s newest redheaded mother.” The Sporting News reported: “Long after the game Hilda was still outside Ebbets Field, displaying her flowers to all and sundry.”51 In 1955, the Dodgers announced their all-time all-star team, as determined by fan vote. A ceremony was held at Ebbets Field on August 14. Various Dodgers who were present and in the stands or dugouts were acknowledged. They included Billy Herman, Leon Cadore, Otto Miller, Arthur Dede, Gus Getz, and one non-ballplayer: Hilda Chester.

By the 1950s, Hilda’s mere presence at Ebbets Field was enough to spur on the Dodgers. But she still sporadically employed her lungpower. On one occasion, she yelled to a young Dodgers broadcaster, “I love you Vin Scully!” Apparently, a mortified Scully did not respond, and her follow-up line to him was, “Look at me when I speak to you!”52 Meanwhile, her iconic status was acknowledged by Dodgers ballplayers. Recalled Ralph Branca: “She was better known than most of us, and if you stunk she’d let you know it.” Added Duke Snider, “She’d be in her box by the third-base dugout and keep hollering at you until you acknowledged her.” But the Duke of Flatbush admitted, “She had a great knowledge of the game and of game situations. It was her life.”53

Near the end of the 1955 season, The Sporting News reported that “Dodgers players, headed by Pee Wee Reese (who else?), gave Hilda a portable radio… Now Hilda can tune in on the Bums, wherever they may be.”54 However, “wherever they may be” would soon be a long way from Brooklyn, as it was announced that the team would be abandoning the Borough of Churches and heading west, to relocate in Los Angeles.

Hilda, like all Brooklyn diehards, was furious. At first, she was in denial about the situation. “The Dodgers ain’t gonna move to Los Angeles,” she declared in March 1957. “I saw some games in Los Angeles a few years back. Why, the place was like a morgue…no rootin’…no cheerin’…how are the Bums gonna feel at home there?”55 As the days turned to months, though, it became clear that the Dodgers’ new anthem would be “California, Here I Come.” Writing in the Los Angeles Times in July, Jeane Hoffman declared, “If you want one reporter’s opinion, our guess is that if L.A. comes up with what O’Malley wants, the city has got him—even if Brooklyn threw in the Gowanus River and Hilda Chester to try and keep him there.”56

Of course, the Dodgers did leave after the 1957 season. During their inaugural campaign in Los Angeles, the closest they got to Brooklyn was Philadelphia, when they played the Phillies—and Hilda pronounced that she “wouldn’t be caught dead” there.57 In June 1958, Dick Young quoted her from her perch selling hot dogs at one of the New York racetracks: “You oughta hear how the horseplayers talk. They hate O’Malley.”58

In 1960, upon the razing of Ebbets Field, Hilda and five members of the Dodger Sym-Phony appeared on Be Our Guest, a short-lived CBS-TV program. (The other guests included Ralph Branca, Carl Erskine, and Phil Silvers Show regulars Maurice “Doberman” Gosfield and Harvey Lembeck.) Hilda joined the Sym-Phony in performing a number, to the tune of “Give My Regards to Broadway,” which included a revised lyric: “Give our regards to all Dem Bums and tell O’Malley, ‘Nuts to you!’” Hilda asked host George DeWitt if the show was being broadcast in color. The answer was “black-and-white,” which displeased her because she had dyed her hair for the occasion. She and the musicians were described as being “still Dodger rooters, but only for the departed Brooklyn club.” All were given original Ebbets Field seats.59

A year later, it was announced that Hilda “will be honored as America’s No. 1 baseball fan” during ceremonies at the opening of the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas.60 But then she quietly faded from view. Occasionally, her name would pop up in the media. In 1963, Dan Daniel noted that “the last I heard of Hilda was that she was employed by the Stevens brothers in their commissary department at the New York race tracks.”61 Still, she steadfastly maintained her Dodger ties. In 1969, Dixie Walker noted that he hadn’t been back to Brooklyn “for years” but was quick to add, “Ah, but last September I got a birthday card from Hilda Chester. She never misses a one.”62 Rumor had it that she no longer resided in the New York metropolitan area. “I understand she’s in retirement in Florida,” declared Dodgers super-fan Danny Perasa.63 However, Dick Young reported that “the cowbell-ringing zany of the old Dodger days” is “ill at age 71. Drop her a note at: 144–02 89th Avenue, Queens, N.Y. 14480.”64

In the early 1970s, Hilda’s address became the Park Nursing Home in Rockaway Park, Queens. Writer Neil Offen showed up at the home with the intention of interviewing her. “I’m sure she won’t want to talk, not about baseball, not about those days,” explained a nursing home employee. “She doesn’t like to talk about them anymore. She doesn’t even like to talk about them to us.” However, Offen got to speak with Hilda on the telephone. “The old days with the Brooklyn Dodgers, no, that’s out,” she insisted. She noted that there was “no particular reason” for her reluctance to reminisce, but she quickly added, “It’s all over, that’s it. That’s the only reason. I’m sorry. That’s all I can say. I’m sorry. But it’s all over. That’s it. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”65

Hilda Chester was 81 years old when she passed away in December 1978. Matt Rothenberg, Manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, reported that she died at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in Queens and was buried in Mount Richmond Cemetery on Staten Island, which is operated by the Hebrew Free Burial Association.

What emerges here is that, for whatever reason, Hilda’s indigent state was not addressed by any surviving family member. According to the Association’s mission statement, “When a Jewish person dies and has no family or friends to arrange for the funeral, or if the family cannot afford a funeral, we assure that the deceased is treated with respect demanded by our traditions. The deceased is buried in Mount Richmond Cemetery in Staten Island where our rabbi recites memorial prayers over the grave. Whether they die in a hospital, nursing home, or a lonely apartment, the New York area’s poorest Jews are not forgotten.”66

Various sources list Hilda’s death date as December 1. However genealogical researcher Scott Wilson reported that her fate was altogether different—albeit no less tragic. According to Wilson, she “died alone at 81 at her home at Ocean Promenade, Far Rockaway, Queens. Found December 9, with no survivors or informant, she was taken first to Queens Mortuary, then to Harry Moskowitz at 1970 Broadway, through the public administrator. Buried December 15, 1978, and a stone placed by the Hebrew Free Burial Association in the 1990s, sec. 15, row 19, grave 7, Mt. Richmond Cemetery…”67 Andrew Parver, the Association’s Director of Operations, confirmed Wilson’s reportage and noted: “It doesn’t appear that she had any relatives when she died.” He added that Hilda’s “stone was sponsored by an anonymous donor” and that “our cemetery chaplain has a vague recollection of someone visiting the gravesite more than 15 years ago.”68

At her passing, Hilda was the definition of a has-been luminary—and her demise went unreported in the New York media. But in subsequent years, her memory has come alive in the hearts of savvy baseball aficionados. Events sponsored by The Baseball Reliquary, which was founded in 1996 and describes itself as “a nonprofit, educational organization dedicated to fostering an appreciation of American art and culture through the context of baseball history,” begin with a ceremonial bell-ringing which pays homage to Hilda. All attendees are urged to bring their own bells and participate in the ceremony.

“It’s a great way to engage the audience and a perfect way to remember Hilda,” explained Terry Cannon, the organization’s Executive Director.

Additionally, The Reliquary hands out the Hilda Award, which recognizes distinguished service to the game by a baseball fan. According to Cannon, the prize itself is “a beat-up old cowbell…encased and mounted in a Plexiglas box with an engraved inscription.” But he was quick to note that, while Hilda is the Reliquary’s “unofficial symbol” and “perhaps baseball’s most famous fan,” she remains “somewhat of a mystery woman. I’m not aware of any existing family members…. Had she died today, of course, that news would have been on the front page of every paper in New York.”69

Hilda also has a presence at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, where an almost life-size fabric-machê statue of her and her cowbell, sculpted by Kay Ritter, is displayed with several other ballyard types. Hilda is all smiles as she rings her bell; affixed to her dress is a button that says: “I’LL TELL THE WORLD I’M FROM BROOKLYN N.Y.” Three years after her death, she was a character in The First, the Joel Siegel-Bob Brush-Martin Charnin Broadway musical about Jackie Robinson. And thirty-plus years after her passing, Howling Hilda (also known as Howling Hilda and the Brooklyn Dodgers), a one-person biographical musical set at the start of the Dodgers’ 1957 season, was penned by Anne Berlin and Andrew Bleckner and presented at various venues.

“I happened upon her and her story quite by accident and fell in love with her instantly,” explained Berlin. “She was one of the most colorful people I had ever read about…. She had a very musical sounding voice to me. With musicals you have to have a voice before you can tell a story. Hilda Chester was all voice—I could hear her voice clearly and thought she would make a wonderful subject for a musical.

“I think she was ahead of her time. Today her cowbells would be tweeted—pictures of her would be on Instagram. She would have a Facebook page called The Brooklyn Dodgers’ Greatest Fan. She knew how to market herself. She took an interest and love and made herself indispensable to it…. She’s coarse, abrupt, gruff, but at the same time she’s someone who can’t get enough of these guys. This was her family. She’s a product of her class, her environment, and Brooklyn. I feel the Dodgers were her family—her real family did not matter to her.”70

Hilda Chester may be long-gone, but she is not forgotten—and, if she could speak today, her response to all the hubbub surely would be: “Ain’t it t’rillin’!”

ROB EDELMAN teaches film history courses at the University at Albany. He is the author of “Great Baseball Films” and “Baseball on the Web,” and is co-author (with his wife, Audrey Kupferberg) of “Meet the Mertzes,” a double biography of I Love Lucy’s Vivian Vance and famed baseball fan William Frawley, and “Matthau: A Life.” He is a film commentator on WAMC (Northeast) Public Radio and a contributing editor of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide. He is a frequent contributor to “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game” and has written for “Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond;” “Total Baseball;” “Baseball in the Classroom;” “Memories and Dreams;” and “NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture.” His essay on early baseball films appears on the DVD Reel “Baseball: Baseball Films from the Silent Era, 1899–1926,” and he is an interviewee on the director’s cut DVD of “The Natural.“

Acknowledgments

Audrey Kupferberg; Lois Farber; Murray Polner; Jean Hastings Ardell; Anne Berlin; Jim Gates, Matt Rothenberg, Sue MacKay, and Cassidy Lent of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; Terry Cannon of The Baseball Reliquary; Andrew Parver, Director of Operations, Hebrew Free Burial Association; Mark Langill, Team Historian and Publications Editor, Los Angeles Dodgers.

Additional Sources

Jean Hastings Ardell. Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Notes

1.Interview with Murray Polner, March 21, 2015.

2. Peter Golenbock. Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984, 60.

3. http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/more-sports/duke-snider-brooklyn-dodgers-boys-summer-baseball-treasure-ebbets-field-article-1.117552.

4. http://articles.latimes.com/2013/may/01/sports/la-sp-erskine-20130502.

5. J.G.T. Spink. “Looping the Loops.” The Sporting News, April 22, 1943, 1.

6. Thomas Oliphant. Praying for Gil Hodges: A Memoir of the 1955 World Series and One Family’s Love of the Brooklyn Dodgers. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005, 158.

7. https://familysearch.org/search/collection/1202535.

8. Rich Podolsky. “The Belle of the Brooklyn Dodgers.” Saratoga Summer 2003, Summer, 2003.

9. Margaret Case Harriman. “The Belle of the Brooklyn Dodgers.” Good Housekeeping, October 1945, 257.

12.http://www.aagpbl.org/index.cfm/profiles/chester-bea/213.

13.Jim Sargent. We Were the All-American Girls: Interviews with Players of the AAGPBL, 1943–1954. Jefferson, North Carolina, MacFarland & Company, 2013, 105.

14.Dan Parker. “The Broadway Bugle.” Montreal Gazette, May 24, 1948, 15.

15.Mildred Danenhirsch. “The Miss of Tomorrow.” Thomas Jefferson High School Yearbook, June, 1939, 75–76.

17.“Child Box Fund Brings $2,000 to Hebrew Orphans.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 23, 1932, 6.

18.“Asylum Given Substantial Aid By Auxiliary. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 14, 1933, 22.

19.http://www.brownstoner.com/blog/2012/09/walkabout-saving-abrahams-children.

20.“Hilda Clings to Lip, Clangs for Giants.” The Sporting News, August 18, 1948, 14.

21.Louis Effrat. “Whatever Hilda Wants, Hilda Gets in Brooklyn.” The New York Times, September 3, 1955, 10.

22.Carl E. Prince. Brooklyn’s Dodgers: The Bums, the Borough, and the Best of Baseball: 1947–1957. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, 89.

24.Sam Davis. “No Fair Weather Fans in Flatbush, and When You Hear the Gong, It’s Hilda Chester Time at Ebbets Field.” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, September 28, 1943, 6.

25.“Sincerely Yours: Ralph Trost Answers the Mail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 27, 1943, 9.

26.Hugh Fullerton, Jr. “Sports Roundup.” The Gettysburg Times, February 3, 1944, 3.

27.“Brooks’ No. 1 Fem Fan ‘Benched’ By Illness.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 21, 1941, 1.

28. http://www.brooklynvisualheritage.org/howlin-hilda-misses-dodgers.

29. “It’s All Over, Terry, Our Ace Feminine Fan Is On the Mend.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 3, 1941, 3.

30. “Defies Doctors’ Orders to See Dodger Games.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1941, 1.

31. “Sincerely Yours: Ralph Trost Answers the Mail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 21, 1942, 9.

32. Jack Cuddy. “Leo’s Alleged Lawsuit Divides Brooklyn Fans.” Los Angeles Times, June 12, 1945, 10.

34. “Flock Is Getting Into Shape Fast.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 22, 1943, 9.

35. Jerry Mitchell. Sports on Parade. New York Post, January 29, 1943, 41.

36. Louis Effrat. “Dodgers Set Back Braves in 10th, 8–7.” The New York Times, August 6, 1944, S1.

37. Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Short Shots in Sundry Directions.” The New York Times, June 12, 1947, 34.

38. Alice Hughes. “A Woman’s New York.” Reading Daily Eagle, April 29, 1943, 14.

39. Oscar Ruhl, “Purely Personal.” The Sporting News, August 12, 1943, 9.

43. Tommy Holmes. “Daze and Knights.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 22, 1953, 9.

44. “‘McPhail’s Order’ for Leo Proved to Be Work of Hilda.” The Sporting News, April 4, 1956, 16.

45. Tommy Holmes. “Dodgers Drop 9th Straight, 7 to 4.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 8, 1943, 24.

46. Paul Gould. “Even Hilda Quits Dodgers, shifts to Yankee Stadium.” The Sporting News, April 9, 1947, 20.

47. “George Currie’s Brooklyn. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 9, 1947, 3.

48. “Hilda Clings to Lip, Clangs for Giants,” 14.

49. Oscar Ruhl. “From the Ruhl Book.” The Sporting News, May 3, 1950, 21.

50. Roscoe McGowen. “Dodgers Overcome By Braves, 7 to 4; Defeat 9th in Row.” The New York Times, August 8, 1943, S1.

51. (Roscoe) McGowen, “Hilda, Now Redhead, Gets Big Bouquet From O’Malley.” The Sporting News, May 20, 1953, 11.

52. http://lasordaslair.com/2012/01/21/dodgers-in-timehowlin-hilda-chester.

54. Roscoe McGowen. “It Was 25-Man Job,’ says Smokey, Dodging Orchids.” The Sporting News, September 14, 1955, 5.

55. “Hilda Claims Bums to Stay.” Toledo Blade, March 8, 1957, 31.

56. Jeane Hoffman. “Soul of Irish Charm: O’Malley Adopts ‘Wait and See’ Policy in Face of N.Y. Headlines.” Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1957, C-6.

57. Gay Talese. “Brooklyn Is Trying Hard to Forget Dodgers and Baseball.” The New York Times, May 18, 1958, S3.

58. Dick Young. “Clubhouse Confidential.” The Sporting News, June 18, 1958, 19.

59. “Hilda and Sym-Phoney [sic] Band Bid Adieu to Ebbets Field.” The Sporting News, February 17, 1960, 27.

60. “Hilda Chester to Be Cited as Top Fan at NBC Tournament.” The Sporting News, February 15, 1961, 21.

61. Dan Daniel. Mary, Lollie, Hilda—Loudest Fans in Stands.” The Sporting News, February 2, 1963, 34.

62. John Wiebusch. “Dixie…Hilda…Leo…Shades of Daffy Dodgers.” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1969, F1.

63. Michael T. Kaufman. “For the Faithful, There Will Never Be a Coda to the Sym-Phony of the Brooklyn Dodgers.” The New York Times, April 11, 1971, 77.

64. Dick Young. “Young Ideas.” The Sporting News, February 15, 1969, 14.

65. Neil Offen. God Save the Players. Chicago: Playboy Press, 1974, 96–97.

66. http://www.hebrewfreeburial.org/what-we-do.

67. Scott Wilson. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of Over 10,000 Famous Persons. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007, 134.

68. Interview with Andrew Parver, April 22, 2015.

69. Interview with Terry Cannon, March 24, 2015.

70. Interview with Anne Berlin, March 12, 2015.