Examining Stolen Base Trends by Decade from the Deadball Era through the 1970s

This article was written by John McMurray

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

This article was honored with a SABR Analytics Conference Research Award in 2016.

In 1976, for the first time in thirty-three seasons, total stolen bases exceeded total home runs in Major League Baseball.1 A consistent turn towards more frequent basestealing had already become evident on the field, as teams collectively stole over 1,000 more bases in 1976 than they did only three years earlier. This sea change invites consideration of the factors that led to the spate of stolen bases which characterized baseball in the mid-1970s.

If it is true that baseball trends run in cycles, the Deadball Era was when the stolen base was paramount; the 1920s was a time of transition, when home runs gained on stolen bases before overtaking them by the end of the decade; the 1930s and 1940s were decades of relative stability between home runs and steals; the 1950s were the low point in major league history for stolen bases; and the 1960s brought a renewed use of the stolen base, culminating in the extremely high totals of the 1970s and beyond. Considering each of these time periods will help to explain why stolen bases increased so dramatically during the 1970s and will underscore how substantial the shift towards stealing bases became during that decade.

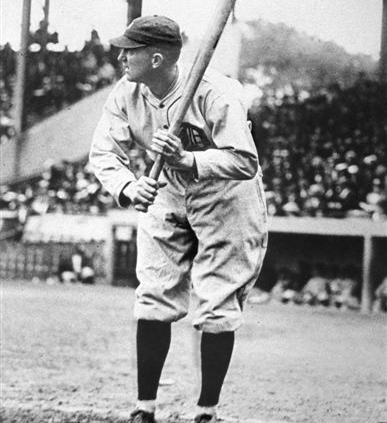

The Early Twentieth Century: Basestealing as a Primary Focus

Perhaps the most telling statistic in all of base-stealing history is that major league teams from 1906 through 1909 averaged more than 10 stolen bases for every home run hit, with a peak of 11.8 steals per home run in 1909. This single-minded focus on stolen bases captures a core characteristic of the Deadball Era, where scoring was low and stolen bases, with the frequent complementary use of bunting and hit-and-run plays, were high. That teams in the American League from 1910 through 1914 and teams in the National League in 1905 and 1911 averaged at least 200 stolen bases per season—an enormous feat, never approached since—plays into this image.

But the Deadball Era was not about all stolen bases. Following the 1916 season, stolen bases declined in every season through 1919 in the American League and plunged similarly in the National League, albeit with an uptick in 1919. By the end of the Deadball Era in 1919, stolen base totals had fallen by nearly 40 percent from their peak roughly a decade earlier.

Indeed, the 1919 season was a sign of things to come, as total home runs in major league baseball nearly doubled from the year prior. While it is reasonable to see baseball as a game driven by stolen bases, particularly during the first sixteen years of the twentieth century, the philosophical shift toward employing fewer stolen bases, likely shaped by changes in managerial philosophy stemming from offensive woes derived from pitchers scuffing the baseball, began in 1916.2 From a stolen base perspective, it is quite reasonable to consider the last three years of the Deadball Era as being stylistically removed from the first 16 years. The introduction of the livelier baseball in the next decade would mean that fans would never again see the stolen base as the primary driver of baseball offensive success.

The 1920s: Home Runs Overtake Stolen Bases

The plunge in stolen bases during the next decade is made evident by two statistics: after 1920, no player in the major leagues stole as many as 60 bases during the rest of the decade, and only twice in either league from 1921 through 1929 (the National League in 1921 and 1923) did teams collectively average more than 100 stolen bases. A 1922 article in The Literary Digest noted the pronounced decline, commenting that “the last few seasons have seen a falling-off in base-stealing so pronounced as to prove alarming to any one who wishes to see baseball preserved as a well-rounded game in every department.”3

The change in style of play was striking. The same article in The Literary Digest bemoaned the loss of stolen bases at the expense of the livelier ball, saying: “Is it not time that this most interesting, most thrilling of baseball plays should be rescued from the slow-moving but iron-bound tendencies of the modern game which are crushing out its very existence?”4 Further, the author cited the loss of unpredictability in the game as stolen bases diminished: “The stolen base is the most perfect example in baseball of the unexpected. In attack it is the farthest removed from the established rule. It injects an element of uncertainty into the game very welcome in these days of crystallized baseball methods. It allows scope for human initiative which is also very welcome.”5

In 1922, teams collectively hit more than 1,000 home runs (1,055) for the first time in major league history. Still, there is a frequent misconception that, with the introduction of the livelier ball, teams immediately eschewed the stolen base. In fact, total stolen bases exceeded total home runs in major league baseball in every season until 1929. Moreover, even the 1929 season was only a slight point of inflection, as teams collectively hit only 15 more home runs than they stole bases. Even so, with stolen bases in decline in most seasons during the 1920s after 1923, it was clear that the offensive winds were shifting.

The 1930s and 40s: Establishing a New Normal

What would become a steep decline in stolen bases first became evident in the National League, as from 1931 through 1945, no NL player stole as many as 30 bases in a season. League-leading totals were also often paltry: Stan Hack stole 16 and 17 bases, respectively, in 1938 and 1939, winning the National League stolen base title in ’38 and tying for the league lead in ’39. Even though American League teams routinely averaged about 10 more stolen bases in each season than National League teams during this 15-year period, low stolen base totals increasingly became more commonplace across major league baseball. In 1945, for instance, the Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Athletics, and St. Louis Browns each stole fewer than 30 bases as a team.

The overall ratio of stolen bases per home run remained relatively stable during the 1930s, with teams, for the most part, hitting roughly 1.5 home runs for each stolen base. With the exception of 1943, when total stolen bases actually exceeded home runs once again since comparatively few power hitters were active during World War II and because of the lifeless balata ball that used, the same general balance held true. Moreover, suggested writer Lew King, the falloff in steals was not due to a lack of players who could run. Writing in 1947, King said: “The major leagues boast as many fast men as years ago. But the modern style of play, dictated by the lively ball, has a sedentary effect on all but a few of the speed boys.”6

John Drebinger, writing in Sportfolio in 1947, suggested that the downturn in stolen bases during the late 1940s was a result of managers becoming risk averse on the bases, given the superabundance of power hitters. Drebinger cited Joe Cronin, who as manager of the Boston Red Sox, mused “Why risk an out simply to gain a base, when most any batter on your club, if he connects properly, can smack it over the fence?”7 At the same time, Drebinger notes that teams in the 1940s were likely to promote “clever” baserunning in lieu of stolen bases.8 Mentioning Billy Southworth as a proponent of this approach, Drebinger said: “Though modern managers are still loathe (sic) to risk signaling for a stolen base, unless gifted with one of those modern rarities like George Case, Pete Reiser, or George Stirnweiss, several have stressed the value of alert, heads-up base running where players are instructed to keep on their toes, take advantage of every slip and at all times be prepared to grab that extra base on a hit.”9

Further, a May 1948 article titled “Is Base-Stealing Becoming a Lost Art?” offered a perspective on why both stolen bases and home runs were higher in the American League than in the National League during this period: “A…logical explanation seems to be that the outstanding basestealers, such as (Ben) Chapman and (Bill) Werber, are in the American League and the tendency always is for teammates and Leaguemates to emulate such examples. Similarly, the prowess of home-run hitters such as Ruth and Gehrig and Foxx in the American League has been the incentive which has steadily increased the rate of home runs in that League.”10

It was in the latter half of the 1940s when stolen bases began to decline most precipitously and home runs began to rise to then-historic heights. In 1949, only six years after stolen bases had exceeded home runs, there were only 730 total steals in major league baseball, while 1,704 home runs were hit. More of the same was to come.

The 1950s: The Nadir of Stolen Bases

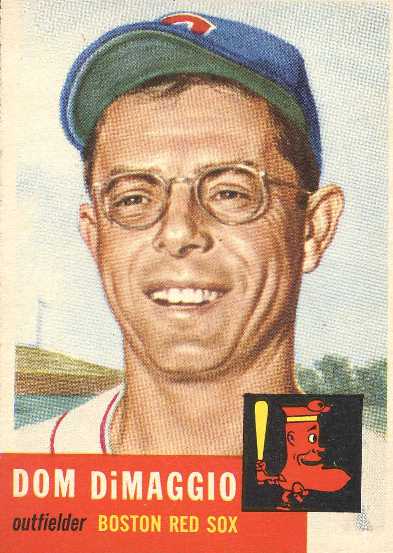

With teams collectively compiling only 650 steals, the 1950 season was the low point for stolen bases in major league history. Dom DiMaggio led the American League with a mere fifteen steals. Eight of the sixteen major league teams stole 40 or fewer bases in 1950, and the St. Louis Browns, Detroit Tigers, and Chicago White Sox each accumulated more outs caught stealing than they did stolen bases.11 In 1950, home runs also outpaced stolen bases by more than one-thousand (1,453) for the first time, a gap which would have been hard to imagine only a decade prior.

With teams collectively compiling only 650 steals, the 1950 season was the low point for stolen bases in major league history. Dom DiMaggio led the American League with a mere fifteen steals. Eight of the sixteen major league teams stole 40 or fewer bases in 1950, and the St. Louis Browns, Detroit Tigers, and Chicago White Sox each accumulated more outs caught stealing than they did stolen bases.11 In 1950, home runs also outpaced stolen bases by more than one-thousand (1,453) for the first time, a gap which would have been hard to imagine only a decade prior.

During the 1950s, some teams did steal bases with regularity. The 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers stole 90, while the 1957–59 Chicago White Sox stole more than 100 bases in each season. The 1959 White Sox, a team bereft of power hitters, won the pennant while stealing more bases than they hit home runs. Such examples, though, were exceptions to the rule.

It is reasonable to infer that the individual philosophies of stolen-base-minded managers in the 1950s, such as Paul Richards and Charlie Dressen, led to their respective teams making more stolen base attempts than others. The same was true in reverse for, say, the Yankees under Casey Stengel or Milwaukee Braves under Fred Haney. The New York Yankees teams of the 1950s surely were slow-footed, but that power-laden team also rarely attempted to steal bases (Billy Martin, for example, was the only player on the 1953 Yankees who attempted as many as 13 stolen bases, stealing only six that season).

Of course, it made sense for teams to eschew stolen bases considering the array of power hitters in the game at the time. In 1956, when teams hit a combined 2,294 home runs—the highest total of the decade—every team in the major leagues other than the Baltimore Orioles hit more than 100 home runs. Clearly, at a time when Ted Williams, Gil Hodges, Duke Snider, Ernie Banks, Larry Doby, Frank Robinson, Vic Wertz, Al Kaline, Eddie Mathews, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Harmon Killebrew, Stan Musial, and Roy Sievers, were all playing, there was little need for most teams to take an extra base.

Billy Evans, then a retired umpire, suggested also that umpires’ refusal to enforce recently-enacted rules requiring pitchers to hold the set position for a full second was another reason why stolen bases fell so substantially in the 1950s. “Unquestionably, this is a good rule if properly enforced,” wrote Evans in 1953. “During the first few weeks of a season a few years ago, the umpires did enforce the rule and chaos resulted. The drastic pitching change apparently came too quickly. Soon the pitchers were back in the old rut—doing just about as they pleased and getting away with it.”12 Hence, without the rule being stringently enforced, Evans implied that runners were held more closely to first base, thus limiting stolen bases.

But, over and above the explanations, the downturn in stolen bases was huge. In 1950, 1953, and from 1955 through 1958, approximately three home runs were hit for every base stolen, a ratio never seen before or since. In the last five years of the decade, more than 2,200 home runs were hit in every season, while teams stole more than 800 bases in only one of those seasons (853 in 1959). Though it was in the direction of home runs rather than stolen bases, it is reasonable to say that the 1950s offered as single-minded a style of play as did the Deadball Era.

The 1960s: A Discernable Upswing

As stolen bases began to rise again in 1959, it spoke in part to the influence of White Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio, who won the American League stolen base title in nine straight seasons, from 1956 though 1964. As Bob Broeg noted: “Not until Luis Aparicio of the White Sox stole 56 in 1959 was there a noteworthy league-leading total over in the A.L. (during the 1950s).”13 After leading the league while stealing fewer than 30 bases during each of his first three seasons, Aparicio, like the rest of baseball’s prominent base stealers, soon began running more.

Aparicio helped to best bridge the gap between the predominantly power-hitting game of the 1950s to the one of the 1960s, where players stealing bases took their place alongside home run hitters. Willie Mays also contributed significantly in that regard. Ultimately, the stolen base landscape of the 1960s was most prominently characterized by four players who together won the stolen base title in every season but one during that decade: Aparicio, Bert Campaneris, Maury Wills, and Lou Brock.14

With his then-record 104 stolen bases in 1962, Wills’ influence on reviving the stolen base as an offensive tool was enormous. According to Leonard Koppett: “when Wills began doing it regularly, the idea of reviving the weapon—not as a special case, but as a regular part of the baseball arsenal—started to grow in other baseball minds.”15 Change was not immediate, as stolen bases did decrease in 1963 and 1964, but Wills laid the groundwork for the emphasis on stolen bases that was to come.

Wills’s achievement of stealing 104 bases in a season was even more staggering given that Aparicio’s American League-leading total from the same year was a mere 31. “How many people realize,” asked Koppett, “that when Wills stole 104 bases in 1962, breaking the record set by Ty Cobb in 1915, Maury’s total was higher than any of the other 19 teams in both leagues?”16

Noting that Babe Ruth’s home run greatness was assured by how far he outdistanced his contemporaries, Koppett also points out that “in 1962, no other player in either league even stole one-third as many bases as Wills…In the 41 years before Wills exploded with the 1962 Dodgers, not a single National League player even stole even half as many bases as Wills did that year. And during the same span, only four American Leaguers did it—barely. Ben Chapman (1931) and George Case (1943) reached 61. George Stirnweiss (1944) had 55 and Aparicio had 56.”17

In 1961, a year before Wills’s record-breaking feat, stolen bases in the major leagues exceeded 1,000 (1,046) for the first time since 1943. They surged to 1,348 in 1962 and stayed high throughout the decade, topping at 1,850 in 1969. But an increased emphasis on stolen bases did not lead to a corresponding fall in home runs. Instead, given the vast collection of power-hitting talent already in baseball, home run totals in the 1960s grew overall throughout the decade.18

The result was a game which, for the first time, employed power and speed with roughly equal effectiveness. Though players would cumulatively steal even more bases and hit more home runs in subsequent decades, the style of play adopted during the 1960s, emphasizing both facets, was the closest approximation to date of baseball as it has been played in more recent decades.

The 1970s: Why Did Stolen Bases Surge in the Middle of the Decade?

While stolen base levels from 1970 through 1973 were, for the most part, in line with 1960s totals, baseball’s emphasis on the stolen base began to increase markedly in 1974. The shift was dramatic: during the 1974 season, teams collectively stole more than 400 bases more than they did during the year prior. Just two years later, in 1976, players would steal more than 3,000 bases, a total last achieved in 1915. With the exception of 1900 through 1903, this three-year period from 1974 through 1976 represented the largest year-by-year increase in stolen bases in major league history.19

While stolen base levels from 1970 through 1973 were, for the most part, in line with 1960s totals, baseball’s emphasis on the stolen base began to increase markedly in 1974. The shift was dramatic: during the 1974 season, teams collectively stole more than 400 bases more than they did during the year prior. Just two years later, in 1976, players would steal more than 3,000 bases, a total last achieved in 1915. With the exception of 1900 through 1903, this three-year period from 1974 through 1976 represented the largest year-by-year increase in stolen bases in major league history.19

Stolen base totals rose in every year but one from 1971 through 1977 (declining only slightly in 1977), before again reaching new modern-era heights in both 1980 and 1983, as well as a modern high in 1987. This sudden flood represented the largest consistent output of stolen bases since the Deadball Era. Once teams broke the 2,000 stolen base threshold in 1973, so began a stretch which has continued unbroken to the present, where teams collectively accumulate at least that many stolen bases in a season. Stolen bases became such a priority that the Oakland A’s, as is well known, provided a roster spot to speedster Herb Washington, whose only role was to steal bases as a pinch runner.

Although home runs did decline a bit in several seasons during this stolen-base surge (most notably, in 1974 and 1976), power numbers were mostly robust throughout the 1970s. Though buoyed in absolute terms by expansion in both the 1960s and 1970s, of course, teams still hit more than 3,000 home runs in four seasons during the decade, occasionally exceeding home run levels which would be reached during the 1990s. With stolen bases and power both being high, steals and home runs were once again generally in a one-to-one ratio during the latter half of the decade, a balance last seen in the 1940s.

The unprecedented emphasis on both stolen bases and home runs during the 1970s raises the question of why stolen bases rose so dramatically after power-hitting had been established for several decades. Considering that each prior era emphasized either home runs or stolen bases, but never both to this degree, it is important to understand the complementary factors which explain why this period in the 1970s broke with convention and ushered in a new style of play.

Four Reasons for the Changes in Style of Play During the 1970s

(1) A Shift in Thinking: Wills, Brock, and Baseball’s Unwritten Rules

In much the way that Ruth provided an example to other players of how they might hit, it is reasonable to infer that Wills’ 1962 performance laid the groundwork for the spate of steals to come in the 1970s. “The answer,” wrote Broeg in 1977, “was probably in the so-called book, that unwritten tome of percentages, of disciplinary do’s and don’ts of the diamond. For instance, you DON’T run when your team is way ahead, players were told. You DON’T run when you’re a couple or more runs behind. Then, along came Wills, who studied the art form and increased his percentage of successes.”20

The upshot, according to Koppett, is that, in time, managers adjusted their approaches accordingly, maximizing stolen bases. “When Wills began (stealing bases) regularly, the idea of reviving the weapon—not as a special case, but as a regular part of the baseball arsenal—started to grow in other baseball minds.”21 Koppett notes that 1970s managers Billy Martin, Chuck Tanner, and Whitey Herzog were all inspired by Wills to expand their base-stealing strategies, saying: “They didn’t get it from Wills; they applied their own ideas to new circumstances that had arisen from Wills’s example.”22

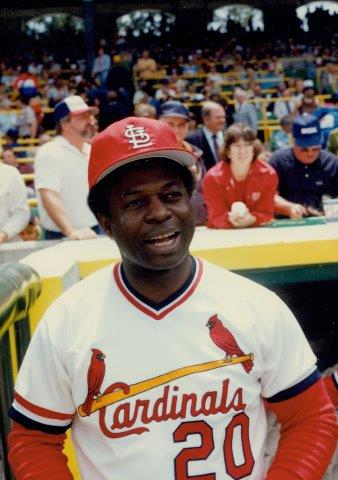

If Wills provided the spark for the stolen base revolution, Lou Brock’s influence kept stolen bases at the forefront. Having already won seven stolen base titles before breaking the all-time single-season record, set by Wills, in 1974, Brock’s example “opened everyone’s eyes to the possibilities” of stealing bases with great frequency.23 In contrast to the more elaborate sliding styles of both Ty Cobb and Maury Wills, Brock also helped to promote a more economical approach to sliding, thus making success at stealing bases easier: “Cobb took a long lead and favored the hook slide, or fadeway. Brock takes a short lead and goes straight into the bag with a quick pop-up, hardly a slide at all.”24

The circumstantial evidence linking Wills, in particular, to a change in contemporary managerial philosophy is strong. As Koppett noted in 1986: “Before Wills, only two players in 40 years had reached 60 stolen bases in a season; once each. Since 1965, in addition to Wills, 11 other players have done it a total of 24 times (including Lou Brock’s record 118 in 1974).”25 It is no coincidence that many of the most successful teams of the 1970s included players who stole bases with the dedication and determination of both Wills and Brock.

(2) A New Trend: Players Who Could Both Hit for Power and Steal Bases

Up to this point, few players in baseball history were capable both of hitting home runs and stealing bases in quantity. More often than not, home runs hitters had been in the mold of Ted Williams, Ted Kluszewski, or Duke Snider—sizeable players who rarely attempted to steal a base—while basestealers resembled Nellie Fox or Max Carey, namely diminutive players who posed little threat of hitting a home run. Though a few players were capable of doing both (Minnie Minoso, Willie Mays, Jackie Robinson, and Chuck Klein among others), it was relatively rare for it to happen in practice.

In contrast, the 1970s style of play, supported by managers who promoted both hitting for power and stealing bases, brought multi-talented players to the forefront, including Don Baylor, Reggie Jackson, and Joe Morgan. Also prominent were speedsters with some consistent power, such as Ron LeFlore, Bill North, Amos Otis, Phil Garner, and Roy White. Never before did baseball have so many active players who could excel at both stealing bases and hitting home runs, albeit in varying degrees.

Contributing to the stolen base surge was the reality that there were fewer pure power hitters than in the decades immediately prior. As Koppett pointed out, “the super-sluggers, of whom Hank Aaron is the last current example, have not been as plentiful as they were a generation ago.”26 Perhaps only George Foster, Greg Luzinski, Willie Stargell, and Tony Perez from the 1970s could be considered to have been in the same mold as the most notable power hitters of the 1950s.

Consequently, a wider range of players was stealing bases than ever before, resulting in many players with a modest number of stolen bases contributing to the high league-wide totals. An American League press release issued on August 2, 1976, noted that “thirty-eight players have already stolen ten bases,” a statistic which comports with most fans’ impressions of the style of play in the 1970s.27 In fact, eight different players won the stolen base title during the 1970s in the American League.

With the exception of 1901 through 1910, when nine different players led or tied for the league lead in stolen bases during those seasons, repeat winners of the stolen base crown were the norm until the 1970s. Then, a wider range came to prominence. In the National League alone, Joe Morgan, Larry Bowa, Dave Concepcion, Davey Lopes, Frank Taveras, and Omar Moreno were only a few of the players other than Lou Brock in the 1970s who contributed significantly to the lofty aggregate stolen base totals. For the first time since the early 1900s, most teams fielded lineups where the majority of players were capable of—and encouraged to—steal bases.

(3) The Development of the ‘Science’ of Basestealing

As basestealing became an integral facet of baseball offenses in the 1970s, with it came more attention to the study of how to steal bases more efficiently. The aforementioned American League press release trumpeted not only the depth of the basestealing pool but also the success rate of basestealers, noting A.L. players as of August 1976 had stolen 68.2 percent of the bases they attempted and that many teams were stealing bases at a better than 70 percent success rate.28 (Ultimately, players would steal 66.4 percent of the bases they attempted in 1976). Part of those successes, which are representative of much of the 1970s stolen base picture, surely stems from better practices.

The Kansas City Royals, a team without much power in the 1970s, worked to increase their stolen base totals by using a stopwatch to gauge which players were getting the best jumps. The result was a more methodical approach to stealing bases, which allowed even slower runners the chance to steal bases effectively when the situation allowed: “We’ve got guys like (George) Brett, (Hal) McRae and Joe Zdeb who aren’t pure baserunners and are the type most clubs wouldn’t give free reign (sic) to,” said Kansas City first base coach Steve Boros in 1977. “But we let them go here because our base running is such a science.”29 Boros noted: “We may not be leading the league in stolen bases, but we’ve got the best ratio,” citing another philosophical trend of the time.30

It is not that players of prior years did not study pitchers’ tendencies when electing when to steal; as Dick Kaegel notes: “The brainy Cobb was the first of the modern players to study and mentally catalogue the movements of pitchers, searching for that one little flaw that would give him the edge.”31 Rather, it was an emphasis on studying combined with modern techniques that made stealing bases profitable: “Years later,” Kaegel continued, “Brock was doing the same thing, adding such refinements as filming pitchers and clocking their motions with a stopwatch.”32

Of course, stolen base strategists had to stay one step ahead of the competition. Melvin Durslag noted in 1977 that basestealers were vexed by opposing management trying to water the infield to slow runners up; pitchers stretching the rules to hold runners on; shortstops leaning towards second base to thwart basestealing attempts; and first basemen relentlessly chatting with baserunners in order to break the latter’s concentration.33 With these impediments, both teams and defenses were strategizing constantly about stolen bases—and how to prevent them. It was a noteworthy change of focus that helped basestealers to proper in the 1970s.

(4) A Decline in Batting Average, and Ballpark Effects

From 1965 through 1972, batting averages were generally lower than they were during the late 1940s and 1950s. The overall major league’s batting average ranged from .237 (in 1968, during the so-called Year of the Pitcher) to .254 in 1970. While teams had generally enjoyed batting averages in the .260’s between 1945 and 1955 and in the .250’s between 1955 and 1964, the decline in batting average from the mid-1960s into the ‘70s obviously made scoring runs more difficult.

With batting averages falling to .244 in 1972, teams sought new ways to score runs. As Koppett said: “In short, it’s no secret that home run totals and batting averages have been much, much lower over the past decade than for the 40 years before that. And the response has been renewed interest in the value of stealing a base.”34 The urgency of taking steps to advance runners, Koppett implies, required a shift in approach: “And as batting averages have dropped, the chance of getting two singles with a man on first has become less, so it has become that much more important to get your man to second so that one single can score him.”35

With the opening of several large stadiums in the early 1970s—including Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, and Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia—it is easy to see why teams emphasized speed over home-run hitting power. Further, the attraction of scoring runners from second base on singles hit on Astroturf surely influenced teams to place an additional premium on fast players. One example of an owner who did so was Charlie Finley, owner of the Oakland A’s, who, according to writer Ron Bergman, had “an obsession with speed.”36

The combination of a dearth of high-average hitters along with spacious ballparks makes the 1970s unique. Although teams continued to hit home runs at a steady rate, they also adopted aspects of Deadball-Era style play when necessary. Yet, beyond that, players in the 1970s were much more able to provide both power and speed whenever necessary, leading the way for Rickey Henderson in the 1980s and foreshadowing a type of player which has become comparatively frequent today.

Summary

The conditions that led to the superabundance of stolen bases in the 1970s were unique, jointly caused by the influence of two prominent basestealers, Maury Wills and Lou Brock; players who were encouraged to use multiple talents; a heightened emphasis on the strategy of basestealing; and circumstances involving batting average and ballpark configuration that made adopting a new strategy imperative. Rarely—if ever—have so many conditions conspired to shift baseball’s style of play. Once baseball players and managers rediscovered the stolen base in the 1970s, it again became a fundamental part of all teams’ offensive approach, rarely flagging even when great sluggers abounded, especially during the two decades to follow. The success that basestealers enjoyed during the 1970s represented a significant and consequential change for the way baseball was played relative to prior decades.

JOHN McMURRAY is chair of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee and the Oral History Committee. He is a past chair of SABR’s Ritter Award subcommittee, which annually presents an award to the best book on Deadball Era baseball published during the year prior. He has contributed many interview-based player profiles to “Baseball Digest” in recent years and writes a monthly column for “Sports Collectors Digest.”

Acknowledgments

With thanks to the Baseball Hall of Fame for providing clippings of vintage articles cited in this piece.

Notes

1. Year-by-year data on stolen bases and home runs used in this article is courtesy of Baseball-Reference.com. In comparing stolen bases over time, it is important to recognize that the definition of what a stolen base is has changed multiple times. One well-known modification to the stolen base rule took place in 1920, when a stolen base would no longer be permitted when there was defensive indifference. When comparing stolen base totals between eras, the differing rules about what a stolen base was at the time obviously impact data comparisons. ↵

2. Referring to the American League and National League only, not including the Federal League. The drop in stolen bases was greater between 1913 and 1915 than it was between 1916 and 1918, but I am referring to when there was an overall change in base-stealing philosophy. ↵

3. “Base-Stealing’s Sensational Decline,” The Literary Digest, April 19, 1922. ↵

4. Ibid. ↵

5. Ibid. ↵

6. Lew King, “The Fleet-Feet Boys,” Baseball Magazine, 1947, 419. ↵

7. John Drebinger, Sportfolio, 1947. ↵

8. Ibid. ↵

9. Ibid. ↵

10.“Is Base-Stealing Becoming a Lost Art?,” National Baseball Hall of Fame Clippings File, publication unknown, May 1948. ↵

11.Strikingly, Detroit players were caught stealing 40 times in 1950 while stealing only 23 bases. ↵

12.Billy Evans, “Base Stealing a Lost Art: Help Needed to Revive It,” National Baseball Hall of Fame Clippings File, publication unknown, March 5, 1953. ↵

13.Bob Broeg, “Wills Triggered a New Steal Era: Few Thefts Before Maury,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1977, 8. ↵

14.The exception was in 1969 in the American League, when Tommy Harper led the league. ↵

15.Leonard Koppett, “Wills Prompted Running Revolution,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1980, 17. ↵

16.Ibid. Koppett credits Wills with breaking Cobb’s record, though Cobb played under a different definition of stolen base. Hugh Nichol still has the most single-season stolen bases, with 138 in 1887. ↵

17.Ibid. It is worth noting that Wally Moses also stole 56 bases for the Chicago White Sox in 1943. ↵

18.Total home runs fell between 1966 and 1968, from 2,743 in 1966 to 2,299 in 1967 to 1,995 in 1968, before rising again in 1969, when baseball expanded. ↵

19.Since stolen bases were not recorded in all seasons, this comment considers only those seasons in which stolen bases were officially recorded. The increase from 1900 to 1903 was slightly greater, as the number of teams doubled. ↵

20.Broeg, 8. ↵

21.Koppett, “Wills Prompted Running Revolution.” ↵

22.Ibid. Koppett wrote that “stealing a lot of bases is a characteristic that runs in ‘families,’” meaning groups of managers. See Leonard Koppett, “Old Orioles Spread Base Theft Gospel,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1976. ↵

23.Leonard Koppett, “Base-Stealing Art Zooming to a Peak,” The New York Times, July 7, 1976, 30. ↵

24.Dick Kaegel, “Fiery Cobb, Cool Brock Got Same Results,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1977, 3–4. ↵

25.Koppett, “Wills Prompted Running Revolution.” ↵

26.Leonard Koppett, “New Era for Base Burglars,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1974. ↵

27.American League press release, “American League Stealing Bases at Blinding Pace,” August 2, 1976. ↵

28. Ibid. ↵

29. UPI, “Stealing’s a Science in Kansas City,” New York Daily News, July 24, 1977, 33C. ↵

30. Ibid. ↵

31. Kaegel, “Fiery Cobb, Cool Brock Got Same Results.” ↵

32. Ibid. ↵

33. Melvin Durslag, “Silence Golden to Base Thieves: Lopes Wants No Lip,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1977, 26. ↵

34. Koppett, “New Era for Base Burglars.” ↵

35. Ibid. ↵

36. Ron Bergman, “Jury Still Out in Case of A’s Hustling Herb,” National Baseball Hall of Fame Clippings File, Publication Unknown (but likely San Jose Mercury News) December 7, 1974. ↵