May The Best Man Win: The Black Ball Championships 1866–1923

This article was written by Todd Peterson

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

In 1892, Frank Grant played for the Gorhams and then the Cuban Giants on his way to a Hall of Fame career. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

During a playoff game in October 1905, Leland Giants pitcher Walter Ball rushed onto the diamond at Chicago’s West Side Park and threw a punch “with all the force of his arm,” at Fred “Pop” Roberts’s face. The Chicago Union Giants second baseman wound up with a large lump over his eye and had to leave the contest, while Ball—who was not even playing that Sunday—broke his own hand. Only the interference of umpire George McGurn prevented the other players from “making a general battle royal.” The Union Giants went on to win, 5–2, but the antagonism between the two squads precluded them from finishing the series.1

The brawl between once-and-future teammates Ball and Roberts illustrates the intensity Black teams brought to playoff encounters. In 1899 the Chicago Tribune speculated that a proposed championship series between the Chicago Unions and Chicago Columbia Giants would be so “fiercely fought” that it would not be surprising “if razors did not take the place of bats before the game was finished.” During the penultimate contest of the 1913 New York Lincoln Giants and Chicago American Giants “world series,” shortstop John Henry “Pop” Lloyd was spiked so badly by a sliding Jess Barbour that an artery in his leg was severed and the future Hall-of-Famer was rushed to Provident Hospital.

African Americans were prohibited from participation in the major leagues (and their precursor the National Association) from 1871 to 1946 (not counting limited opportunities in 1879 and 1884), longer than they have been allowed to participate. For most of that time, top-flight segregated Black baseball teams operated independently without the sanction of an official league. Despite the lack of a league structure, these clubs battled annually for regional and national supremacy.

Far from being a haphazard operation, the anointing of an African American champion was a serious undertaking which, although a more elastic process than its major league counterpart, nevertheless rarely failed to identify the best team. Longtime blackball player and historian Sol White noted in 1906 that such championship contests “occur yearly in colored base ball, East and West, and go far to keep up the interest among colored patrons of the National game.”2

These playoff games generally drew large crowds and generated a lot of money—legitimate and otherwise. Way back in 1877 a New Orleans Times reporter taking in a local Black playoff noted, “besides championship honors the clubs always contend for the possession of a money stake,” and that “promiscuous betting runs riot among their adherents when a game is on.” The result was a “desperately exciting game of baseball,” as the host of enthusiastic fans howled “themselves hoarse” and a “perfect pandemonium marked the progress of the game whenever one nine passed its rival’s score.”3

Shortly after the Civil War, several quality African American baseball teams emerged in urban areas with large Black populations such as Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and New York. Much like their White counterparts, the Black squads grew out of the social clubs of the day, and soon began vying with each other for preeminence. In October 1866 the Bachelor Base Ball Club of Albany, New York journeyed to Philadelphia and handily beat the hometown Pythian and Excelsior nines in match games before large crowds.4

The following year saw an explosion in intercity activity as the Bachelors and multiple outfits from Washington, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn competed for top honors. In October the Brooklyn Unique and Philadelphia Excelsior drew a huge crowd to the Satellite grounds in Williamsburg, New York, to witness their tilt for “the colored championship of the United States.” The contest was a “remarkably lively” one, with both captains threatening to pull their clubs off the field several times after umpiring decisions went against them. The Excelsior were clinging to a 42–37 lead in the seventh inning when it became too dark to see the ball and the game was called in their favor. As the New York Herald reported, “The Philadelphians and their friends reformed in procession and, with the drums and fifes, marched back to the ferry and crossed to this city, highly delighted with their victory.”5

When the dust settled a few weeks later, the Philadelphia Pythian and Brooklyn Monitor had established the most valid title claims, although the two squads did not meet on the diamond. However, after demolishing the Washington Alert and Mutual clubs in the nation’s capital that summer, the Pythian were presented “a rich and massive silver ball and a beautiful rosewood bat,” by that city’s Ladies Croquet Club. The Pythian ultimately settled the question in October 1868 by downing the Monitor, 27–9, at Columbia Park in Philadelphia.6

Although the Pythian remained the team to beat, the epicenter of eastern blackball briefly shifted to upstate New York, where a number of clubs had picked up the Albany Bachelors mantle. In September 1869 the best of them, the Fearless of Utica, swept a home and home set from the remarkably-nicknamed Heavy Hitters of Canajoharie, before challenging, “any colored club that chooses to dispute their claim to the championship.”7 A year later the Mutual of Washington, led by Charles Douglass, son of the great orator Frederick Douglass, undertook a tour of western New York and demolished seven local outfits by an aggregate score of 345–78. The District nine landed in Utica in late August to take on the Fearless for the “championship of the United States.” The two squads played five innings in a “mean” drizzle until the game was called with the Mutual holding an 18–10 advantage. The Washingtonians declared that the contest was halted by agreement of both parties, but the Utica lads “denied having made such arrangement” and claimed a 9–0 forfeit, boasting they were willing to play “until the bases pulled anchor and floated off.”8

Way out west (the Ohio River served as the demarcation point between eastern and western Black clubs), the Chicago Blue Stockings, “dusky athletes who are employed as waiters in the various hotels and restaurants,” captured the “colored championship of Illinois,” during the summer of 1870 by taking two out of three games from the uniquely-named Rockford Pink Stockings. The new champs’ reign was short-lived, as another Windy City squad, the Uniques, poached their slugging catcher “Big” George Brown off their roster the following spring and crushed the Blue Stockings, 39–5.9

In September of 1871, the Uniques undertook the first continental blackball tour, traveling east to play squads in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Troy, New York. The trip climaxed in Philadelphia where the “champion of the west” Uniques split a pair of contests with the “champion of the east” Pythian, before huge crowds on the grounds of the National Association’s Athletics. The series garnered nationwide newspaper coverage as “the fielding of the Unique was very good, as was the batting of the Pythian,” in two well-played games. There would be no rematch. The Unique returned home just in time for the Great Chicago Fire on October 8 which brought a halt to all local baseball activity for a while. The Pythians dissolved after the brutal assassination of their shortstop and captain Octavius Catto during an October 10 election riot.10

The genteel amateurism of the early post-Civil War era gradually gave way to a new breed of elite Black players and teams that played predominantly for money. With the growing commercialism, however, came increased competition and controversy. The first three games of the 1875 western showdown between the revitalized Chicago Uniques and the upstart St. Louis Blue Stockings were marred by biased umpiring, walkouts, stalling, and an unfortunate attempt by Chicago backstop Ben Dyson to throw the series for $25.11

Needing a win to stay alive in the series, the Uniques were leading, 17–14, in the bottom of the ninth inning of the fourth contest at Chicago’s White Stockings Park when umpire William Thacker called the game because of “darkness, crowd, and disputes among players.” Although the St. Louis club had two men on base with none out at the time, the arbiter declared the contest in favor of the Uniques, and “all bets on the grounds were paid.” A few hours later, after learning some of his friends lost money owing to his decision, Thacker reversed himself and awarded a 9–0 forfeit to the Blue Stockings. This came as small consolation to the Blues’ William Pitts and William Mitchell, who were severely injured when the St. Louis squad’s omnibus was stoned by the angry mob that invaded the field.12

The Blue Stockings got a small measure of revenge the following June when they swept the Uniques in St. Louis. After the second contest, the squads retired to Rueben Armstrong’s bar, where “the feeling was of partisan character,” and “a row finally occurred.” During the ensuing melee, Benjamin Beatty of the Chicago squad fired a pistol at the saloon keeper, resulting in his arrest and no more Uniques/Blue Stockings games.13

By the early 1880s, American hotels were regularly employing Black baseball clubs to entertain their guests. In September 1882, one such outfit representing the West End Hotel of Long Branch, New Jersey, dropped a 10–8 decision to the Philadelphia Orions before 500 spectators at New York’s Polo Grounds for the “colored championship.” The West Ends rebounded a year later by crushing the Crescents of Princeton, New Jersey, 20–2, in a “grand colored championship match” at the Polo Grounds.14

In September 1885, Philadelphia’s Keystone Athletic squad, representing the Argyle Hotel of Babylon, New York, took the Orions “into camp by a score of 6-to-4,” before signing three of their number, including pitcher Shep Trusty. With the subsequent backing of Trenton capitalist Walter Cook, the “Babylon boys” became the Cuban Giants, stocking their roster with the best Black players in the country, chief among them Clarence Williams, Bill Whyte, and twirler George Stovey. The Giants completed the 1886 season “with a grand record made against National League and leading college teams,” while establishing their blackball dominance that August by crushing the fledgling New York Gorhams, 25–4, and the more established Brooklyn Alpine, 24–0.15

The success of the Cuban Giants and the plethora of top-flight African American teams throughout the country led to the formation of the first intercity Black leagues. In March 1886 the Southern League of Colored Base Ballists was formed by Jacksonville, Florida, politician and newspaperman John Menard. Consisting of teams from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Tennessee, the rather loose federation operated from June until August. The Memphis Appeal-Avalanche anointed their hometown Eclipse, led by pitcher William Renfroe, champions, although they dropped season series to both the New Orleans Unions and the Louisville Falls City.16

Less successful was the National Colored Base Ball League, which collapsed after a couple of weeks in May 1887. The Cuban Giants opted not to join the six-team circuit, but won 12 out of 14 games against the Philadelphia Pythians, New York Gorhams, Boston Resolutes, Louisville Falls City, and Pittsburgh Keystones, while outscoring the league squads, 159–48.17

In August 1888, a tournament “for the colored championship of the world,” was held between the top four Black clubs in the east. Playing before huge crowds in New York City and Hoboken, New Jersey, the Cuban Giants easily won all five games they played, capturing the silver ball donated by their owner John M. Bright. Sol White’s Pittsburgh Keystones were the surprise of the event, also winning five games, with their two defeats coming at the hands of the Giants. The New York Gorhams finished a disappointing third, while one reporter opined that the winless Norfolk Red Stockings “should never leave Virginia to play ball.”18

Not present at the tourney, but very anxious for a crack at the Giants, were the New Orleans Pinchbacks, the Southwest’s premier Black club. Originally known as the W.L. Cohens, the Louisiana nine dropped an 1886 championship playoff to the New Orleans Unions before changing their name in honor of politician P.B.S. Pinchback, the first Black governor of a US state. The club also swiped three of the Unions’ best players, including pitching phenom George Hopkins, who had struck out ten or more batters in each game that season. In August the Pinchbacks traveled to Illinois, along with “five car-loads of gentlemen” supporters to meet a strong semi-pro club called the Chicago Unions.19

Over 1,500 fans gleefully watched the Unions edge the Pinchbacks, 4–1, in the opener at South Side Park. Joe Campbell struck out 14 batters for the victors, while Hopkins fanned 17 in defeat. The next afternoon, 1,800 cranks turned out to witness an even better game, which the Southerners won, 6–5, on the strength of 20 strikeouts by Hopkins and a two-run ninth-inning home run by their second baseman A. Defauchard. The Pinchbacks took the rubber match, 14–7, a couple of days later as Hopkins whiffed 14 more, giving him 51 punchouts in three games.20

The Pinchbacks, who conversed in “English and French and always swear at the umpire in French,” continued on to St. Louis where they swept a three-game set from the West End club. A strengthened West End squad journeyed to the Crescent City in late October and stunned the Pinchbacks, 4–3, at the New Orleans Ball Park despite 13 more strikeouts by George Hopkins. A persistent rain delayed the second contest between the two clubs for a week, and after it ended in a 3–3 tie the Missouri outfit decided to stick around a few more days to play it off. The West Ends jumped out to a 7–0 lead after 2 1/2 innings, but the Pinchbacks rallied and tied it with two runs in the bottom of the ninth, before W.J. Turner triumphantly crossed the plate with the winning run in the tenth inning as “the crowd went wild.”21

George Hopkins moved north in 1890 to join the Chicago Unions, and Walter Cohen’s Pinchbacks never got their chance to play the Cuban Giants. According to Sol White, the Cubes’ only remaining “full-fledged” rival was the New York Gorhams, although they had a difficult time proving it on the diamond. From August 1886 through 1890, Ambrose Davis’s Manhattan-based club played the Giants over 25 times, but managed only four wins and two ties.22

The only force able to stop the Cuban Giants was their owner John Bright, whose extreme frugality motivated 11 of his players, including superstar pitcher George Stovey, to jump in 1890 to J. Monroe Kreiter’s York, Pennsylvania, franchise in the Eastern Interstate League, where they were renamed the Colored Monarchs. The prodigal players briefly returned to the Giants’ fold in 1891, but in mid-May many of them defected again, this time to Davis’s Gorhams who were operating out of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for the season. The Big Gorhams, as they were popularly known, claimed a 100–4 record, and crushed the Giants five straight times by an aggregate score of 77–22 to finally lay claim to the “colored championship.”23

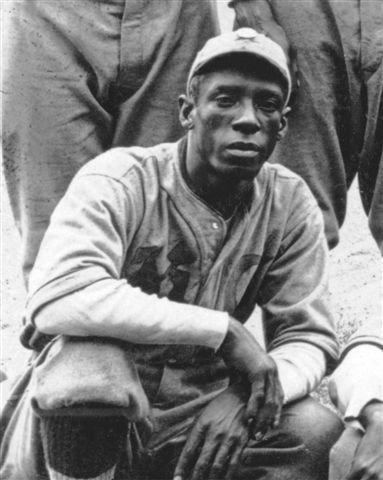

The Gorhams reorganized in the spring of 1892 under the management of one W. Primrose, but John Bright blocked the team from playing games on Long Island and most of their key players, including future Hall-of-Fame infielder Frank Grant, rejoined the Giants. In late September the “Cubes” met the Gorhams, representing the Champlain Hotel of Bluff Point, New York, one final time, demolishing them, 18–1, before a huge crowd of 2,500 on the Long Island grounds.24

By the summer of 1893, boom had given way to bust, for the nation’s economy as well as on the diamond, and Bright’s Cuban Giants were the only professional Black team left operating east of the Mississippi. In October 1894 the Giants ventured to Chicago to take on the Unions, now the premier team of the west. The Giants found the “amateur” Unions “somewhat easy” and swept a two-game set, including a 14–7 shellacking in the opener at South Side Park.25

As the century ran out, two new professional African American clubs rose to challenge the Cuban Giants and Unions. In the fall of 1894 Blackball pioneer Bud Fowler and young slugger Grant Johnson organized the Page Fence Giants in Adrian, Michigan. Financed by a woven wire company and a bicycle manufacturer, Fowler’s novices barnstormed throughout the Midwest in 1895 racking up a record of 118–36–2, while serving notice to the Unions by clubbing them three times by a combined score of 66–21.26

John Bright’s penurious ways led most of his 1895 Cuban Giants to abandon the team en masse the following March and form a new club under the co-op plan (wherein a team’s expenses were deducted from the gate receipts, and the balance split evenly among the players), christened the Cuban X-Giants. Bookkeeper Edward B. Lamar was recruited to keep track of the financial side of the operation as well as to spar with Bright in the press. Lamar challenged the Cuban Giants to a winner-take-all-the-receipts series on several occasions throughout the season, but Bright ignored the defi’s, other than to note that the X-Giants were, “getting most terribly defeated everywhere… thereby injuring the Genuine Cuban Giants’ great reputation.”27

Undaunted, the Cuban X-Giants traveled to Michigan in September to battle the Page Fence Giants for a $1,000 stake and the “colored championship of the United States.” Playing before appreciative crowds in Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana, the young Page Fence squad outscored “the famous sluggers of the East,” 172–137, en route to an 11–8 series win. For their efforts the Michigan lads received “beautiful medals from their manager” and, perhaps more importantly, “extra compensation.” E.B. Lamar claimed that six of the X-Giants had played hurt, but took some solace in the $1,000 purse his club earned after convincingly sweeping a two-game set with the Chicago Unions before heading back to the Big Apple.28

In 1897 the Cuban Giants and Lamar’s X-Giants finally met in an eastern championship series played in New Jersey and Connecticut over the course of an October week. Prior to the playoff, it was unkindly suggested that “both teams will be searched before they enter the grounds to guard against a flourish of razors during the exciting moments of the battle.” The Sunday opener at Weehawken was a hard-fought, back-and-forth affair that the X-Giants managed to tie with two runs in the final frame, before the game was called because of darkness. Lamar’s squad went on to win the title by walloping Bright’s bunch, 28–5, in the next two games before dropping the meaningless Sabbath tilt at Weehawken before a crowd of over 3,000 people.29

After another year of squabbling over players and guarantees, the two squads met again on three successive Sundays in October 1898. The X-Giants copped a wild and wooly first contest in Hoboken, with James Robinson leading the way with three hits including a double and a home run. “The Black Rusie” also came on in relief and pitched three scoreless innings to close out the 9–7 win. When the teams returned to Hoboken a week later, “the arguments between the players were more lively,” and “hostilities threatened to break out” on several occasions. The hard luck “Genuine” Cuban Giants out-hit and out-fielded their rivals but fell, 7–6, after their two-run ninth-inning rally was snuffed out by a great stop and throw by the X-Giants second baseman Ross Garrison. Lamar’s charges also won an anticlimactic third match, 17–10, at Newark. That was enough for John Bright. The two clubs never played for the championship again.30

The East-West barnstorming playoffs lasted for a few more years, however. A couple of weeks before the X-Giants final tussle with Bright’s Cuban Giants, Lamar’s squad schooled the Chicago Unions by winning six out of nine games played in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana. The X-Giants returned to the Midwest in June 1899 and their “superior hitting” helped them down the Unions 11 games to seven before several “enormous” crowds.31

The Unions and Page Fence Giants generally avoided each other, getting together for only a game or two each year. In 1899 the Michigan team relocated to the Windy City and became the Chicago Columbia Giants. Acquiescing to public demand, the two squads agreed to meet in a winner-take-all-receipts, best-offensive series in September. Playing before crowds in excess of 9,000, the Columbia’s big southpaw George Wilson out-dueled fellow lefty Bert Jones in the two first matches, 1–0 and 4–2. In the third game, shortstop Grant “Home Run” Johnson mashed a grand slam off Jones, the object of a bidding war between the clubs that spring, to launch the Giants to a 6–0 victory and net them “a big bunch of money.”32

The Cuban X-Giants ventured west again in June 1900 and the Unions finally defeated their old nemesis, thrashing Lamar’s club 12 games to five. The three-week series culminated with a “brilliant” 6–3 victory in Chicago, as Bert Jones scattered five hits and scored two runs to aid his own cause. According to Sol White, “the western teams won as they pleased this year.” The Columbia Giants walloped John Bright’s Cuban Giants in another June showdown that began and finished in Chicago. Columbia’s George “Rat” Johnson clouted a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth inning of the denouement to give George Wilson an “exciting” 10–9 win.33

The Unions and Columbia Giants renewed their conflict that October, splitting a pair of games and tying another, leaving the “colored championship of the world” “undecided.” In July 1901 the Unions’ traveling secretary, Frank Leland, effectively stole most of the team from owner William Peters and formed a new squad called the Chicago Union Giants. Leland’s outfit and the Columbia Giants faced off that fall at South Side Park to settle “the colored championship.” The Columbias won a pair of games to nab the title, with Will Horn scattering six hits and Harry Buckner crushing a run-scoring triple in the 3–2 climax.34

Unable to find suitable grounds in Chicago, the Columbia Giants relocated to Big Rapids, Michigan, during the 1902 season, and hooked up with the Union Giants one last time to settle scores. Leland’s squad took two out of the first three games at Chicago’s South Side Park, behind its 23-year-old Texas wunderkind twirler Andrew Foster, who fanned ten batters while vanquishing the Columbias, 7–3, in the opener. Foster had left the Union Giants by the time the clubs met up again in Big Rapids in late August. The Chicago nine captured one game, but the Michigan squad’s own 19-year-old wonder boy pitcher, Johnny Davis, won two decisions in as many days to deadlock the season series.35

Harry Buckner’s RBI triple cinched the 1901 title for the Columbia Giants. (TODD PETERSON)

In 1903, Davis and many other former Columbia Giants joined an emerging Iowa concern called the Algona Brownies. The Hawkeye club beat Leland’s Union Giants 10 games to five for the western title. The series culminated in Des Moines in August and a bench-clearing, bat-swinging, donnybrook broke out during the penultimate contest after Union Giants catcher Andrew Campbell slammed into his opposite number, George “Rat” Johnson, at home plate. The rival backstops exchanged punches, touching off a melee that ended only after several policemen stormed the field. Johnson had the last laugh as Algona won, 2–0, to capture the crown.36

Several other Chicago ballplayers, including Harry Buckner and Bill Monroe, headed east in 1903 to play for a rising powerhouse named the Philadelphia Giants. Sol White, along with sportswriters H. Walter Schlichter and Harry Smith, had organized the Pennsylvania squad the previous summer, recruiting several former Cuban X-Giants along the way. Lamar’s squad initially rebuffed offers to play White’s new charges, but after “two years of squabbling, challenges, and counter challenges” the clubs agreed to meet in a best-of-nine championship series in the fall of 1903.37

The playoff, contested over two weeks in Brooklyn, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, was “fought with the bitterest feeling,” with the X-Giants prevailing by winning five of the first seven games. Andrew Foster, who had joined Lamar’s unit in June, dominated the event, winning all four of his starts, fanning 21 batters while allowing only six runs. Foster also banged out six hits, including a double and triple, while X-Giants first baseman Robert Jordan led all batters with a .560 average.38

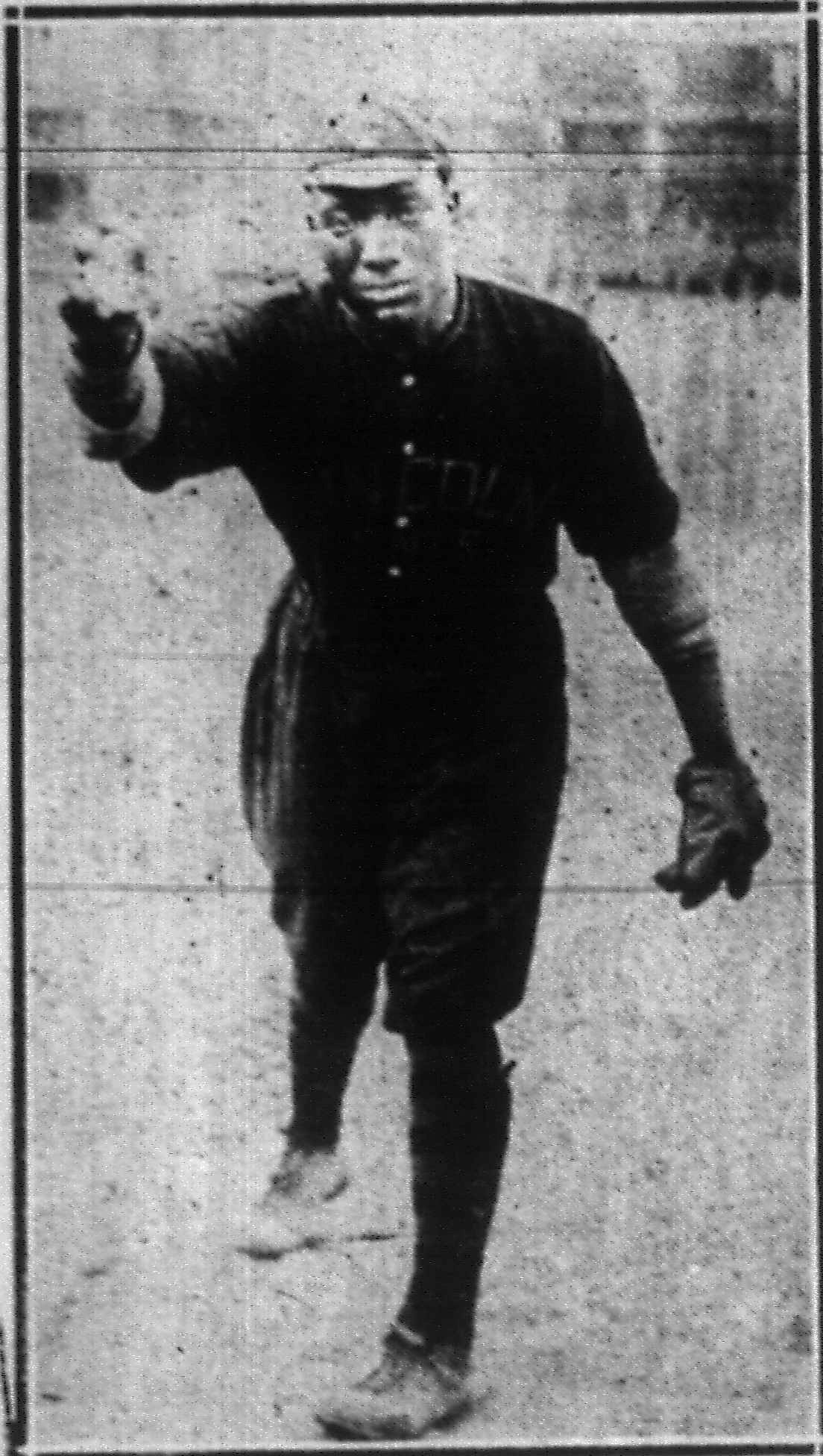

Young Andrew Foster was a wunderkind pitcher in 1902 when he broke into the top ranks with the Union Giants. He would go on to become one of the dominant figures in Negro Leagues baseball for more than two decades. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Proving the eternal blackball adage, “If you can’t beat them, steal them,” Sol White enticed Foster (now called Rube) to join the Philadelphia Giants the next season for $90 a month, and he again proved to be the difference-maker in another fall playoff between the rival clubs. White’s squad captured two out of three bitterly fought games before enormous crowds at Atlantic City’s Inlet Park. The burly Texan won the first and last contests, striking out 18 batters in the initial go-around, and giving up but two hits in the finale. Foster also batted .400, tempering some of the damage caused by X-Giants second baseman John “Pat” Patterson who hit two home runs in the series and stole five bases.39

A dispute over Cuban pitcher Jose Muñoz precluded the X-Giants and Philadelphia Giants from playing each other in 1905. The following year both squads joined the International League of Independent Professional Baseball Clubs, an interracial eastern semipro circuit. After splitting their first two contests, the teams met in a Labor Day doubleheader at Philadelphia’s Columbia Park to resolve the league championship. More than 12,000 fans, the largest blackball crowd ever, looked on as starters Rube Foster and Harry Buckner were each reached for ten safeties. The Phillies got to Buckner “when bingos meant runs” however, while Foster twice retired the X-Giants with the bases full to nab the essential 3–2 victory, earning the beautiful silver cup donated by circuit president William Freihofer. Philadelphia also won the second game 4–1. This was the end of the line for Edward Lamar’s nine. The following April it was announced that “the Cuban X-Giants have retired from the field.”40

While the Philadelphia Giants reigned supreme in the east, the western blackball title still ran through the Windy City. To avoid confusion with William Peters’ Chicago Unions, Frank Leland rechristened his squad the Leland Giants in February 1905. To add to the confusion, Peters appropriated the Chicago Union Giants moniker for his club. The two teams met at Auburn Park on four consecutive Sundays in October 1905 to decide matters, with Johnny Davis pitching the Lelands to an 8–2 triumph in the opener. The Union Giants held late leads in the next two contests, but the Lelands rallied to tie them both before darkness fell. George Wilson and George “Rat” Johnson returned from Renville, Minnesota, to lead the Unions over their rivals 5–2 in game four, with Walter Ball’s assault of Fred Roberts putting an end to the series. Auburn Park was again the locale the following October when Leland’s squad twice shut out the Union Giants by identical 5–0 scores, effectively finishing them as a top-flight unit.41

In the fall of 1906 Walter Schlichter and promoter Nat Strong organized the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs of the United States and Cuba, a rather informal organization consisting of the Philadelphia Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Giants, and Abel Linares’s Cuban Stars. The member clubs agreed to play a minimum of five games against each other in various eastern locales, including Philadelphia, Harlem, and Atlantic City. The title came down to a late September confrontation at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. The Philadelphia Giants, with Hall-of Famers Pete Hill and John Henry Lloyd, edged the Royal Giants, 4–2, as Dan McClellan scattered six hits to nail down the club’s fourth consecutive championship.42

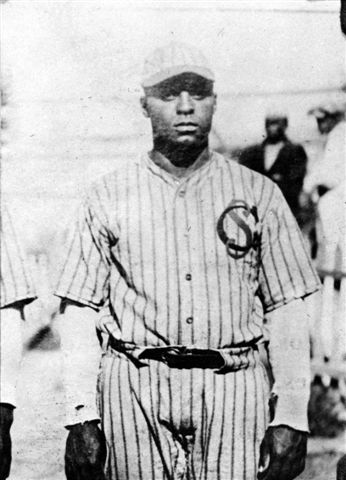

John Henry Lloyd, known as Pop, was one of two future Hall of Famers to play for the 1906 Champion Philadelphia Giants. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Upset with Walter Schlichter’s cost-cutting measures, Rube Foster jumped to Chicago in 1907 to join the Leland Giants, bringing along seven other top eastern players. In June 1908 Foster put up a $2,500 purse of his own money and offered to take the Lelands to Philadelphia to play Schlichter’s club for either a percentage or winner-take-all. Instead the Phillies traveled to the Windy City in late July for a showdown series. The Chicago squad won three out of the first four contests before Philly twirler Harvey Martin, instructed by Sol White to “just spit on the ball and let it go,” downed the Lelands on two consecutive days to even matters, and the locals declined to play off the tie. Quakers shortstop John Henry Lloyd “was a whale at fielding and batting,” during the six games, collecting 11 hits (five off of Foster) and scoring 10 runs.43

In July 1909 the Leland Giants journeyed 400 miles northwest to play the St. Paul Gophers, a crack unit comprising several former Chicago players as well as infielder Felix Wallace, former Birmingham Giants third baseman “Candy” Jim Taylor, and his pitching sibling, “Steel Arm” Johnny. The Gophers took three out of five thrilling games played at St. Paul’s tiny Downtown Park, with John Taylor out-dueling Giants lefty Charles “Pat” Dougherty, 3–2, in the finale. Sore loser Rube Foster, who had missed the series with a leg injury, later snarled that “no man who ever saw the Gophers play would think of classing them as world’s colored champions.”44

Frank Leland responded to the defeat by signing five Gophers, including Wallace and the Taylor brothers, to his new squad, the Chicago Giants, during the off season. Foster and Leland parted ways in September 1909, with Rube curiously retaining the Leland Giants designation and his old boss keeping most of the roster. Foster held on to Pat Dougherty and Pete Hill, and signed several eastern stars for his squad, including John Henry Lloyd. The big Texan claimed to have the “best colored team in the world,” but for whatever reason his wrecking crew didn’t face a really top-flight contender in 1910. Frank Leland took his Chicago Giants back to the Twin Cities in July however, where they easily won four out of five games from the Gophers to nab the “world’s colored championship.” “Cyclone” Joe Williams, a 24-year-old flame thrower from Texas, fanned 18 batters in winning two contests, while Felix Wallace cracked a couple of homers against his old mates.45

The eastern blackball scene was also fragmenting. The Philadelphia Giants disbanded in July 1911 shortly after their 21-year-old hurler “Cannonball” Dick Redding and his battery-mate Louis Santop joined the Lincoln Giants, a new Harlem-based squad assembled by Sol White. The Lincolns, owned by promoter brothers Jess and Eddie McMahon, helped mitigate the collapse of Nat Strong’s league when John Connor’s Royal Giants met the non-sanctioned club in a playoff. Eastern honors, however, came down to a three-game set, each contested for a $1,000 purse, between the Lincoln Giants and the Cuban Stars. Hall-of-Famer Jose Mendez started all three games for the Cubans and won twice, fanning 21 batters as the Islanders copped the series two games to one. Over 20,000 fans turned out to witness the first two contests at the American League Park in New York.46

Jose Mendez started all three games for the Cuban Stars and won twice to capture “Eastern” championship honors in 1911 over the Lincoln Giants. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The 1911 western title was decided in July, when Rube Foster’s newly-minted Chicago American Giants downed Frank Leland’s heavily favored Chicago Giants six games to two. Playing before record-breaking crowds at Schorling Park, the American Giants rotation of Bill Lindsay, Pat Dougherty, and Frank Wickware outpitched “Cyclone” Joe Williams, Walter Ball, and “Big” Bill Gatewood to annex the series, while their teammate Pete Hill punched out 14 hits, including three doubles and a homer. The loss cost Leland a $500 side bet with Foster and triggered his club’s decline, with most of his top players seeking employment elsewhere the following season.47

During the ensuing decade, the leading Eastern Black club would often venture west in late summer, usually to play the American Giants for the “Independent” championship of the United States. Although their title claims were rather presumptuous, the Brooklyn Royal Giants invaded Chicago in 1912 but met with little success, being swept in six games by Foster’s men. The Royals returned to the Windy City in 1914 under the management of Nat Strong, who had wrested control of the squad from John Connor, but despite the presence of emerging ace William “Dizzy” Dismukes, Brooklyn lost all seven games with the American Giants.48

Sol White wrote in 1906 that “when teams travel to a far section of the country to meet for a championship struggle, there is always given to the visitors a most hearty welcome.” Things had changed by July 1913, when Rube Foster brought his American Giants to New York. After splitting four contests with the Royal Giants, Foster trotted out Frank Wickware to pitch the opener against the Lincoln Giants at Olympic Field. Problematically, the “Red Ant” had accepted $100 to start for the Lincolns only a few days before, and the managers of the two clubs argued for over an hour as to Wickware’s eligibility before the match was called off. In the four games the clubs did play, Joe Williams pitched the Lincolns to two victories; the clubs battered each other to an 11–11 tie; and the American Giants staged a furious ninth-inning rally to pull out the fourth contest 6–5. The teams were to play a fifth time, but Foster protested the Lincoln’s substitution of Royal Giants Frank Earle for the ailing Jude Gans and the game was cancelled, disappointing another large gathering.49

Enormous crowds also turned out at Schorling Park when the teams reconvened in Chicago a week later. Foster imported “Steel Arm” Johnny Taylor to start one contest and his Hall-of-Fame brother Ben to play first base, but to no avail as the Lincolns captured six of ten games to decisively win the championship. Joe Williams was the key to the scrap, winning five times, while tossing nearly 65 innings for the pitching-depleted Easterners. John Henry Lloyd batted .319 for the New York squad before being injured, and the ageless wonder Grant “Home Run” Johnson chipped in with a .316 mark. As usual, Pete Hill led the Chicago cause with a .333 average, but he did not register an extra base hit. Even notorious sore loser Foster allowed that the Lincolns’ “great playing and wonderful defense was never surpassed, if equaled on any diamond,” although he also blamed the Chicago fans for not rooting vociferously enough for his squad.50

In late August it was reported that several Lincoln Giants hadn’t been paid their full salaries in weeks because of financial reverses the McMahons had incurred from their boxing promotions. After running afoul of Nat Strong, the brothers lost control of their club to New York hustler Charley Harvey. Undeterred, the pair formed a new squad called the Lincoln Stars in the spring of 1914, and eventually signed up several members of their old cast including John Lloyd, Dick Redding, and center fielder Spottswood Poles. The two Lincoln outfits would not play each other, but the McMahon team went to Chicago in the summer of 1915, splitting a classic 10-game set with the American Giants before Foster’s club edged them four games to three in a 1916 rematch.51

Dick Redding was one of the former Lincoln Giants who joined the Lincoln Stars in 1914. (TODD PETERSON)

The season of 1915 also found the American Giants in a bitter regional imbroglio with the Indianapolis ABCs. The Hoosier club, under the management of cagey South Carolinian Charles Isham Taylor, featured a devastating lineup that included C.I.’s brother Ben, shortstop Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss, and 18-year-old center fielder Oscar Charleston. Foster’s club took three out of five June games from the talented Indianapolis squad at Schorling Park, with soft tossing “Dizzy” Dismukes garnering the two ABC wins. A month later at Indianapolis’s Federal League Park, the “Taylorites” beat the Giants four straight times to eliminate Chicago from “the colored championship of America,” but not before Foster pulled his team from the field in the first contest, complaining of poor playing conditions. Pete Hill was allegedly struck on the nose by a police officer, C.I. Taylor and Chicago second baseman Harry Bauchman got into a shoving match, and another local cop threatened to “blow Rube’s brains out.” A motivated Pete Hill slammed four home runs in the final two matches, while an incensed Rube Foster declared that C.I. Taylor was “down and dirty,” an “ingrate,” and a “stool pigeon,” after which the ABCs manager threatened a libel suit.52

Foster and Taylor met in Indianapolis in July 1916 to bury the hatchet and schedule another round of games beginning in late August. Any thought that the clubs’ behavior might improve was quickly dispelled in the opener in Chicago when the ABCs Bingo DeMoss took a swing at umpire Harry Goeckel after being called out on a close play at home. C.I. Taylor was tossed out of game two for arguing with the arbiter and the American Giants proceeded to take three out of the first four contests, before the finale ended in a 3–3 tie.53

The series resumed in Indianapolis in late October. The Giants copped the first game, 5–3, before “Dizzy” Dismukes pitched the ABCs to three victories and the Indianapolis squad won another contest by forfeit when Rube Foster pulled his club off the field after being ejected for refusing to remove a fielder’s mitt while coaching at first base. The championship belonged to Taylor’s nine again, although Foster groused that as twelve games had been originally agreed to, it was “impossible” for either side to claim victory.54

Unable to beat the ABCs, Rube swiped one of their best players, Bingo DeMoss, and signed eastern ace “Cannonball” Dick Redding for good measure. Between June and early September 1917, the American Giants and Taylor’s outfit faced off 25 times, with Foster’s revitalized club taking 19 out of those contests. Dick Redding won eight out of his nine decisions against the Hoosier squad, and put the exclamation mark on the Giants’ championship on August 19 by dominating the ABCs, 4–2, before 7,000 unhappy fans at Indianapolis’s Washington Park.55

The American Giants’ next regional challenge came in 1919 from the Detroit Stars, a newly-formed club featuring several Foster cast-offs including player-manager Pete Hill. The clubs began their series in June, and the Giants, propelled by the devastating Hall-of-Fame outfield tandem of Oscar Charleston and Cristobal Torriente, captured five of the first six contests. The talented Stars, featuring blackball greats John Donaldson, Jose Mendez, “Candy” Jim Taylor, and emerging slugger Edgar Wesley, rebounded to win the next five games, outscoring the Giants, 50–27, before Chicago ace Dick Whitworth stopped the carnage and evened things up with a 9–1 victory.56

At age 18, Oscar Charleston played with the Indianapolis A.B.C.’s in many 1915 grudge matches against Foster’s club—and by 1919 would join them. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Due to the terrible Chicago race riots that summer, the Giants were forced to contest most of the playoff in the Motor City. The clubs settled matters during a weekend in early August. Ironman twirler Andrew “Stringbean” Williams allowed but two safeties, outdueling the great Donaldson as Chicago took the opener, 2–1. Veteran Giants third baseman Bill Francis doubled and tripled the next day as the “Fosters” wrapped up another title with a 5–3 triumph.57

While the American Giants dominated the west, the Brooklyn Royal Giants and Lincoln Giants battled for eastern supremacy. From 1912 through 1919 the two squads clashed in doubleheaders about every other Sunday and almost always on Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Labor Day. At stake was the eastern crown which was captured by the Lincolns in 1912, 1913, 1914, and 1917. The Royal Giants finally broke through and annexed the title in 1916, while in 1918 each squad won nine games against each other and ran out of season before playing off their tie.58

For several seasons, fireballers Joe Williams and Dick Redding gave the Lincolns a devastating 1–2 punch, before the “Cannonball” departed for other pastures. From 1911 through 1916 (save 1915 when the Royal Giants were on hiatus) Redding posted a 17–7–1 record versus the lads from Brooklyn and on two occasions he started and won both ends of a doubleheader against them. “Cyclone” Joe was victorious in 24 out of 35 decisions against the Royal Giants between 1912 and 1920, including six shutouts.59

The two aces “held grievances against each other for some time,” however, and Redding matriculated to the Lincoln Stars and the American Giants before hooking up with the Royal Giants in the spring of 1918. Pitching against each other for the first time, Redding posted three straight decisions over Williams before being called up by the US Army. The “Cannonball” briefly returned to Brooklyn the next season, and the Cyclone edged him, 1–0, in the series opener, tossing a no-hitter while fanning 12 batters, before the “biggest gathering” in Olympic Field history.60

In the spring of 1919, former Brooklyn owner John W. Connor retooled a middling Atlantic City nine called the Bacharach Giants by raiding his old club for Dick Redding, John Henry Lloyd, and catcher Ernest Gatewood, leaving the Royal Giants lineup “practically shot to pieces.” A similarly depleted Lincoln squad waxed the Brooklyn squad in nine of their 12 meetings that summer, led by Joe Williams, “without whom there would be no team.”61

Neither the Lincolns nor Brooklyn would play Connor’s renegades, but he discovered a suitable foil from the Philadelphia suburb of Darby. Over the course of the preceding decade, postal employee Ed Bolden had transformed the Hilldale Athletic Club boy team into a powerhouse professional outfit, featuring such up and comers as outfielder George Johnson and spit-balling ace Phil Cockrell. Hilldale won three out of the first five games with the Atlantic City nine in early June, before their veteran center fielder Spottswood Poles jumped to the Bacharachs. When the two squads played again in late August before 15,000 frenzied fans in Atlantic City, Hilldale catcher Yank Deas “said something to Poles in whispered tones,” instigating a fight between the two that escalated into a bench-clearing brawl that was finally stopped by the Atlantic City police. The Darbyites pulled out a 1–0, 10-inning victory, but the Bacharachs, due in no small part to 11 base hits by Poles, proceeded to win the next five games to capture the eastern crown.62

Both the Detroit Stars and Chicago American Giants ventured east in the summer of 1919 to play Hilldale and the Bacharachs, with the four clubs splitting a handful of games. The emergence of so many financially viable professional teams led to the organization of the Midwestern-based Negro National League in February 1920. Not surprisingly, Foster’s American Giants, led by Cristobal Torriente, southpaw twirler Dave Brown, and third baseman Dave Malarcher proved to be the association’s dominant force, capturing the first three pennants.63

Rube Foster’s entreaties to expand the NNL out east were rebuffed by the area moguls, although Connor’s Bacharachs joined as an associate member. Various antipathies among club owners left the 1920 eastern title chase in a muddled state. The Bacharach Giants refused to play the Royal Giants or Hilldale because of their “league agreement,” although player raids and lawsuits between the squads probably also played a part. Conversely, the New York Age doubted the Lincoln Giants could call themselves champions “and have anyone except their owners recognize their claim unless they play every team in the field to oppose them.”64

In June Lincoln captain Joe Williams approached John Connor about “crossing bats” and the clubs scheduled two midsummer doubleheaders at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Dick Redding pitched his club to three victories, including a pair of shut outs over Joe Williams as the Bacharachs claimed a share of the eastern championship. A crowd of about 16,000 “clamorous fans” watched the initial clash, while threatening weather and a transit strike kept the crowd down to about 10,000 for the second double-dip.65

In August the Bacharachs headed west to take on the American Giants. The Bees captured the first match in Gary, Indiana, by a score of 11–4, but lost all three played at Schorling Park. The Atlantic City outfit’s belligerent behavior was also called into question, with third baseman Oliver Marcell being censured “for making immoral movements with parts of his body that would resemble a hoochy-coochy dancer.” In October the two clubs hooked up again and divided a string of games played throughout the eastern seaboard, with Dick Redding downing the Westerners three times, twice by shutout. The series concluded with a Sunday doubleheader at Ebbets Field. A ninth-inning triple by Chicago pinch hitter George “Tubby” Dixon off Redding gave the American Giants a 2–0 win in the opener, and they grabbed the five-frame finale, 1–0, as well.66

Under the leadership of John Henry Lloyd, the Brooklyn Royal Giants underwent a revival in 1920 and by season’s end were also proclaiming themselves “Colored World Champions.” In the first half of the season, the Royals copped three out of five games from their old rivals, the Lincoln Giants, with two of their wins coming on ninth-inning rallies. From June through mid-October the Brooklyn squad battled Hilldale in another “championship series.” Brooklyn won six games against four defeats and two ties, as John Lloyd collected 14 hits in the series, including a three-run game-winning homer, and turned “many base hits into outs by his flashing fielding.” Lloyd left Brooklyn the following year to manage the Columbus Buckeyes and by the end of the decade the Royal Giants had degenerated into “a mediocre bunch without an outstanding player.”67

Hilldale became an NNL associate member in 1921 and resumed its rivalry with the Bacharach Giants. The two split 18 decisions from June through October, with the Darbyites barely outscoring their rivals, 96–92. Connor and Bolden scheduled a doubleheader at New York’s Dyckman Oval on October 30 to break the tie. Phil Cockrell scattered five hits while Otto Briggs, Louis Santop, and Chaney White all homered in Hilldale’s 7–2 triumph. The Quaker nine was leading, 2–1, in the second contest when it was called because of darkness and the title was theirs.68

Foster’s Giants were also prowling the East that October, playing both contenders. In a series that lasted over three weeks, the American Giants bested the Bacharachs by a single game. Dave Brown shaded Dick Redding, 5–4, in the decider, aided by Dave Malarcher’s sixth-inning home run. Chicago also took two out of the first three contests against Hilldale, as left fielder Jimmy Lyons ran wild on the bases, stealing home twice. After a hard fought 5–5 tie, Bolden’s ace Phil Cockrell downed the Giants for the second time, clubbing three hits on his own behalf including a homer, in a 15–5 rout that evened the series. Former American Giants twirler Dick Whitworth shut down his old mates on three hits in the last game. His new teammates reached curveballer Bill Holland for 11 safeties, and Hilldale wrested “championship honors” with a 7–1 triumph. The predictably ungracious Rube Foster moaned about the ditch-lined outfield at Hilldale Park and that the Darby club refused to abide by the “playing rules.”69

John Henry Lloyd displaced Dick Lundy as manager-shortstop of the New York version of the Bacharach Giants the following season. From Memorial Day through the Fourth of July, the Bees and Hilldale played five doubleheaders before crowds averaging in excess of 10,000 fans, to decide the eastern crown. John Connor’s club captured six of 10 games in a heavy-hitting series, although Bolden’s outfit outscored them, 67–61. John Lloyd registered a trio of three-hit games for the Gotham crew, while George Johnson laced over 15 base hits for Hilldale, and mashed four home runs in the Memorial Day twin-bill in Darby.70

The Bacharachs had opened the season by beating the American Giants three out of five times in Chicago and they returned in August to renew their struggle with the NNL leaders. The clubs halved the first four games at Schorling Park, with catcher Julio Rojo twice driving home the game-winning run in the Bacharachs final at bat and the American Giants bunting their way to a 7–2 triumph in the fourth match despite managing only four base hits.71

Both owners desperately wanted to win the finale, which turned out to be “one of the greatest games played anywhere,” replete with “brilliant fielding, eight fast double plays, and catches after long runs.” Bacharach twirler Harold Treadwell fanned 12 and scattered eight hits while blanking the American Giants for 19 innings. But his teammates could do nothing with Chicago starter Ed “Huck” Rile or Dave Brown, who came on in relief in the fifth. The jug-eared lefty allowed only six singles for the next 15 frames, and struck out 12 batters, including a bases-loaded punchout of George Shively in the top of the 18th inning. In the bottom of the 20th, Cristobal Torriente drew a walk off Treadwell, was sacrificed to second, and scored the game’s only run on a single by Dave Malarcher, beating weak-armed right fielder Ramiro Ramirez’s throw home by five feet.72

Three days later, Hilldale followed the Bacharachs into Chicago for another five game set. Spitballer Phil Cockrell did Treadwell and Brown one better, tossing a no-hitter while walking only three batters during the Easterners’ 5–0 triumph. The American Giants won the next two contests before Cockrell, who “throws a mean, mean baseball,” flummoxed Chicago 5–3 on four hits. It was déjà vu all over again in the bottom of the 12th inning of the deciding game, when Giants first baseman Leroy Grant drew a walk and later beat a throw home by Hilldale’s Hall-of-Fame shortstop Judy Johnson to give the Fosterites a 7–6 win.73

In 1923 both Hilldale and the Bacharachs severed their association with the NNL and threw in with Nat Strong to form the Eastern Colored League (ECL). During the next two years, the ECL raided the western circuit for several players, including Hall-of-Famers Oscar Charleston, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, and Ben Taylor, thus rendering any regular or postseason activity between the two organizations extremely unpalatable.74

In early September 1924, NNL czar Rube Foster and the ECL owners hammered out their differences in “one of the most peaceful meetings in the history of organized Colored baseball,” and agreed to stage a best of nine game “world’s series” in October. After nearly 60 years the blackball championship had seemingly hit the big time.75

There should be little dispute that the majority of the blackball playoffs were contested by squads of big-league caliber. Previous research has revealed that the African American teams beat major leaguers in head-to-head competition nearly 60 percent of the time and defeated minor-league outfits at about the same clip the American and National league clubs did.76

While no one is asking the New York Yankees to give back any of the titles they won during the segregated era, it seems obvious that more recognition needs to be given to the Black champions and their achievements. In the fall of 1905, Philadelphia Giants owner Walter “Slick” Schlichter challenged the winner of the upcoming World Series to determine, “who can play base ball best—the White or the Black American.” Schlichter’s defy was ignored by the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Giants, prompting Sol White to postulate:

Of course, there is a possibility of the colored man winning and that would be distasteful to many followers of the White team, but true sport recognizes no color nor clan and it should always be, may the best man win.77

TODD PETERSON is a Kansas City-based visual artist, historian, and educator. He was a recipient of Yoseloff-SABR Baseball Research Grants in 2006 and 2010, and received the Normal “Tweed” Webb Lifetime Achievement Award for outstanding research at the 2009 Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference. Peterson is the author of “Early Black Baseball in Minnesota” (2010) and is currently working on a book about the Negro League playoffs for McFarland and Company, as well as a graphic novel about John Donaldson.

Notes

1 Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 23, 1905; Chicago Record Herald (Illinois), October 23, 1905.

2 Sol White, History of Colored Base Ball, With Other Documents on the Early Black Game 1886–1936, Compiled and introduced by Jerry Malloy (Lincoln, Nebraska and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 35.

3 New Orleans Times (Louisiana), September 4, 1877.

4 Albany Evening Journal (New York), September 27, October 5, 1866; Syracuse Daily Standard (New York), October 4, 1866.

5 New York Herald (New York), October 4, 1867.

6 National Republican (District of Columbia), September 2, 1867; Anthony DiFiore, “Advancing African American Baseball: The Philadelphia Pythians and Interracial Competition in 1869,” Black Ball 1, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 60.

7 Utica Daily Observer (New York), September 10, 21, 1869.

8 Buffalo Evening Courier and Republic (New York), August 22, 26, 1870; Utica Daily Observer (New York), August 22, 24, 1870; New York Clipper (New York), September 3, 1870; Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington DC: National Geographic, 2006), 11–12.

9 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), August 24, 1870; Michael E. Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 28; James E. Brunson III, The Early Image of Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009), 38; Chicago Times (Illinois), May 31, 1871.

10 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), September 19, 1871; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), September 18, 20, October 11, 12, 1871; New York Tribune (New York), September 18, 1871; Milwaukee Sentinel (Wisconsin) September 21, 1871; Brunson, 43.

11 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), September 8, 1875; Brunson, 42, 61.

12 St. Louis Republican (Missouri), September 9, 1875; Brunson, 67;St. Louis Daily Globe (Missouri), October 15, 1875; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 14, 15, 1875.

13 St. Louis Daily Globe (Missouri), June 14, 16, 1876.

14 Brunson, 112; New York Globe (New York), July 28, August 18, 1883; New York Herald (New York), September 13, 1882, September 7, 8, 1883.

15 White, 8, 10, 12; Trenton True American (New Jersey), August 14, 1886; Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), August 25, 1886.

16 Bill Plott, “The Southern League Of Colored Base Ballists,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 3 (1974) ; Thomas Aiello, “A Case For The Negro Southern League,” 13th Annual Jerry Malloy Conference Booklet, 2010; New Orleans Times Picayune (Louisiana), June 7, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, July 31, August 2, 1886; New York Freeman (New York) August 14, 1886.

17 New York Clipper (New York), February 11, 1887; Sporting Life (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), June 1, 1887; Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), November 3, 1887.

18 White, 16; New York Age (New York), August 25, September 1, 1888; New York Sun (New York), August 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 1888; New York Herald (New York), August 23, 1888.

19 St. Louis Republic (Missouri), August 28, 1888; New Orleans Times Picayune (Louisiana), October 25, November 15, 1886; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), August 19, 22, 1888.

20 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), August 22, 25, 1888; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), August 22, 23, 24, 26, 1888; St. Louis Republic (Missouri), August 26, 1888.

21 St. Louis Republic (Missouri), August 26, 27, 29, 1888; New Orleans Times Picayune (Louisiana), August 29, October 29, November 1, 2, 1888.

22 St. Louis Republic (Missouri), August 28, 1888; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), August 26, 1888; White,14; Cleveland Gazette (Ohio), March 22, 1892; New York Herald Tribune (New York), September 9, 1887, September 19, 1888; New York Sun (New York), July 16, 1888; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), August 2, 3, 1889.

23 White, 16, 18, 20, 150, 151; New York Sun (New York), May 20, 21, 1891; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), April 20, June 26, 1891; New York Herald (New York), May 18, 19, July 14, 27, October 5, 12, 1891; Harrisburg Patriot (Pennsylvania), June 12, 13, 15, 1891; Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), June 16, 17, 1891.

24 White, 24; Harrisburg Patriot (Pennsylvania), September 21, 1891; New York Herald (New York), March 16, September 26, 1892; Cleveland Gazette (Ohio), March 22, 1892; Pittsburgh Courier (Pennsylvania), March 12, 1927.

25 White, 24, 37; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), September 14, 1891, October 6, 1894; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 23, 1893; New York Sun (New York), October 7, 1894.

26 White, 24, 37; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), September 14, 1891, October 6, 1894; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 23, 1893; New York Sun (New York), October 7, 1894.

27 Lomax, 145–146; New York Sun (New York), August 15, 1896; Washington Times (District of Columbia), May 23, 1896.

28 White, 37; Lima Times Democrat (Ohio), September 12, 1896 Sporting Life (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), October 31, November 14, 1896; Adrian Daily Telegram (Michigan), September 26, October 3, 1896; Lomax, 152.

29 Jersey City News (New Jersey), October 6, 1897; New York Sun (New York), October 4, 5, 1897; Jersey City Journal (New Jersey), October 11, 1897.

30 Sporting Life (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), March 26, April 16, November 5, 1898; Jersey City Journal (New Jersey), October 3, 10, 1898.

31 Sporting Life (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), November 5, 1898; Janesville Daily Gazette (Wisconsin), July 3, 1899; White, 37–38.

32 Lomax, 159–160, 166; White, 38; Illinois Record (Springfield, Illinois), March 18, 1899; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), April 8, September 3, 4, 18, 25, 1899.

33 White, 38, 40; Janesville Daily Gazette (Wisconsin), June 12, 1900; Oak Park Times (Illinois), August 10, 1900; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), June 25, July 2, 1900.

34 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), October 8, 14, 1900, September 29, 1901; Jackson Citizen Patriot (Michigan), October 17, 1900; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 14, 1901; Lomax, 171; Frank Leland, Frank Leland’s Baseball Club, (Chicago: Fraternal Printing Co., 1910), 5, 7.

35 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), July 28, August 4, 1902; Robert Peterson, Only The Ball Was White (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 104; Big Rapids Pioneer (Michigan), July 23, August 20, 21, 1902.

36 White, 40; Des Moines Register and Leader (Iowa), August 10, 1903; Upper Des Moines Republican (Iowa), August 12, 1903; Maxwell Tribune (Iowa), August 13, 1903.

37 White, 31, 40.

38 White, 40, 42; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), June 28, September13, 18, 1903; Camden Post Telegram (New Jersey), September 14, 16, 26,1903; Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), September 15, 1903.

39 White, 44, 46, 146; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), September 2, 3, 4, 1904.

40 Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles, Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume Three (Charleston, South Carolina, 2006), 55; White, 33; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), May 8, September 4, 1906, April 14, 1907.

41 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), February 26, October 2, 9, 1905, October 22, 1906; Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October 16, 23, 1905, October 15, 1906; White, 46.

42 Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), October 29, 1906, October 14, 1907; New York Press (New York), September 22, 1907.

43 Chicago Defender (Illinois), February 20, 1915; Leland, 6; Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), June 27, 1908; October 2, 1909, March 5, 1910; Chicago Tribune, 1908 July 28, 29, 30, August 3, 7, 8, 1908.; Sol White, New York Age (New York), January 10, 1931

44 St. Paul Pioneer Press (Minnesota), July 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 1909; Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), November 13, 1909.

45 Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), October 2, November 13, 1909; St. Paul Pioneer Press (Minnesota), July 25, 26, 27, 28, 29.

46 New York Age (New York), August 3, 10, 24, September 7, 21, 1911; The New York Times (New York), August 20, 1911; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), September 5, 1911.

47 Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), July 8, 1911; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), June 29, July 3, 4, 5, 6, 30, 31, 1911; Chicago Examiner (Illinois), July 7, 1911.

48 Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle (New York), March 30, 1916; Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), June 1, 1912; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), March 4, 1913; Chicago Defender (Illinois), September 12, 1914.

49 White, 35; New York Age (New York), July 17, 24, 1913; Chicago Defender (Illinois), July 26, 1913.

50 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), July 28, 29, 30, 31, August 1, 10, 13, 14, 1913, Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), August 16, December 20, 1913.

51 New York Age (New York), August 21, 1913; April 9, 1914; Brooklyn Daily Star (New York), August 21, 1914.

52 Chicago Tribune (Illinois), June 21, 22, 24, 1915; Chicago Examiner (Illinois), June 23, 25, 1915; Chicago Defender (Illinois), July 24, 31, 1915; Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), July 24, 31, August 14, 1915.

53 Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), July 15, 1916; Chicago Defender (Illinois), September 2, 9, 1916; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), August 28, 29, 30, 31, September 1, 1916.

54 Chicago Defender (Illinois), October 28, November 4, 18, 1916; Indianapolis Freeman (Indiana), October 28, November 4, 1916; Paul Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 1997), 69.

55 Chicago Defender (Illinois), January 27, March 17, June 23, July 28, August 11, 25, September 8, 1917; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), June 11, 12, 13, 20, July 16, 17, 18, 20, August 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 1917; Detroit Free Press (Michigan), August 4, 1917; Chicago Examiner (Illinois), August 9, 1917; Debono, 190.

56 Chicago Defender (Illinois), April 5, 1919; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), June 16, 18, 19, 20, 1919; Detroit Free Press (Michigan), July 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, August 1, 3, 4, 1919.

57 Detroit Free Press (Michigan), August 10, 11, 1919.

58 New York Press (New York), September 3, 12, 1912, August 18, 1913; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), September 27, 1914; New York Age (New York), October 12, 1916, October 4, 1917; Chicago Defender (Illinois), October 19, 1918.

59 New York Age (New York), September 28, 1911, June 26, 1913, July 6, 1918, May 10, July 5, 1919; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), September 11, 1916, June 6, 1920; New York Sun (New York), June 25, 1917.

60 Chicago Defender (Illinois), May 18, 1918; New York Sun (New York), June 3, 1918, May 5, 1919; New York Age (New York), May 10, 1919.

61 New York Age (New York) May 10, May 24, 1919; Chicago Defender (Illinois), May 24, June 7, 1919; New York Evening Telegram (New York), May 2, 1920; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), June 9, 1919.

62 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball 1910–1932 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 51–52; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), June 6, 9, 10, 11, August 27, 28, September 9, 1919; Chicago Defender (Illinois), June 14, August 30, September 20, 1919.

63 Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), July 17, 19, August 22, 1919; Bridgeton Evening News (New Jersey), July 19, 1919; Detroit Free Press (Michigan), August 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 1919; Chicago Defender (Illinois), August 30, 1919; Peterson, 83–84, 259; John Holway, The Complete Book Of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half Of Baseball History, edited by Lloyd Johnson and Rachel Borst (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 139.

64 Chicago Defender (Illinois), May 8, 1920; Philadelphia Tribune (Pennsylvania), June 12, September 18, 1920; New York Age (New York), May 22, 1920.

65 New York Age (New York), June 19, July 17, September 4, October 23, 1920; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), July 12, August 30, 1920.

66 Chicago Defender (Illinois), August 14, October 16, 1920; New York Evening Telegram (New York), October 10, 1920; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), October 11, 18, 1920.

67 Washington Bee (District of Columbia), October 2, 1920; New York Sun (New York), May 3, 1920; Brooklyn Eagle (New York), June 6, 1920; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), June 11, September 16, October 15, 16, 1920; Philadelphia Tribune (Pennsylvania), June 19, August 7, 14, September 25, October 9, 1920; Rollo Wilson, Pittsburgh Courier (Pennsylvania), September 15, 1928.

68 Chicago Defender (Illinois), December 11, 1920; New York Evening Telegram (New York), October 26, 1921; Philadelphia Tribune (Pennsylvania), November 5, 12, 1921.

69 Defender (Illinois), October 1, 8, 22, 1921; Chicago Tribune (Illinois), October 24, 1921; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), October 5, 10, 1921; Philadelphia Tribune (Pennsylvania), October 15, 22, 1921.

70 Chicago Defender (Illinois), March 18, June 24, 1922; Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), May 31, June 5, July 3, 5, 1922.

71 Chicago Defender (Illinois), August 12, 19, 1922.

72 Chicago Defender (Illinois), August 26, 1922.

73 Chicago Defender (Illinois), August 26, September 2, 1922.

74 New York Age (New York), December 16, 1922; Lanctot, 93, 97–98;Debono, 95–96.

75 Frank Young, Chicago Defender (Illinois), September 13, 1924; Holway, 192–194; Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2006), 110, 116, 126, 134.

76 Mark Armour, “The Effects of Integration, 1947–1986,” Baseball Research Journal, No. 36 (2007), 54; Holway, 471; Scott Simkus, “The World Was Flat: The Realities and Road Map For Major League Classification (Part One),” Outsider Baseball Bulletin, no. 96 (April 4, 2012), 3–4.

77 White, 49, 51.