Mis-Management 101: The American League Expansion for 1961

This article was written by Eric Thompson - Andy McCue

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

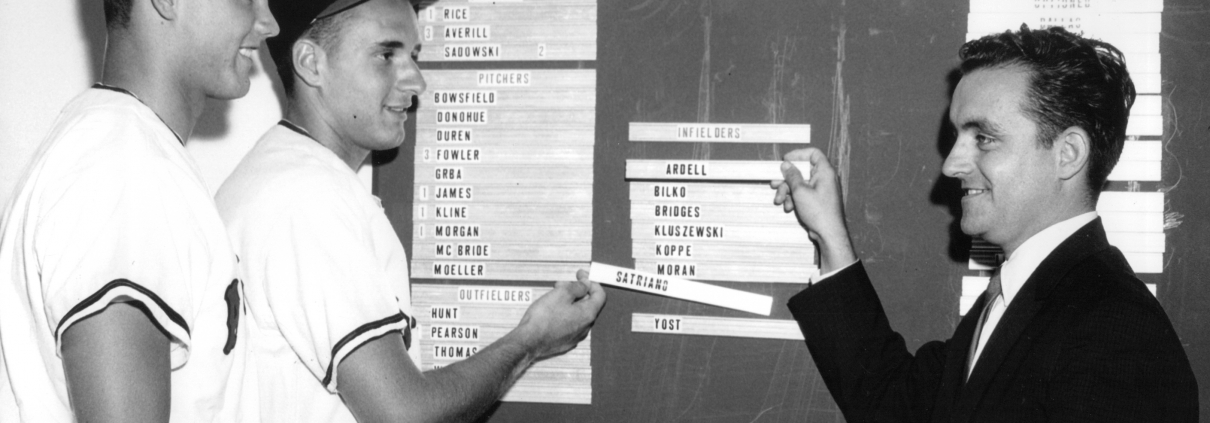

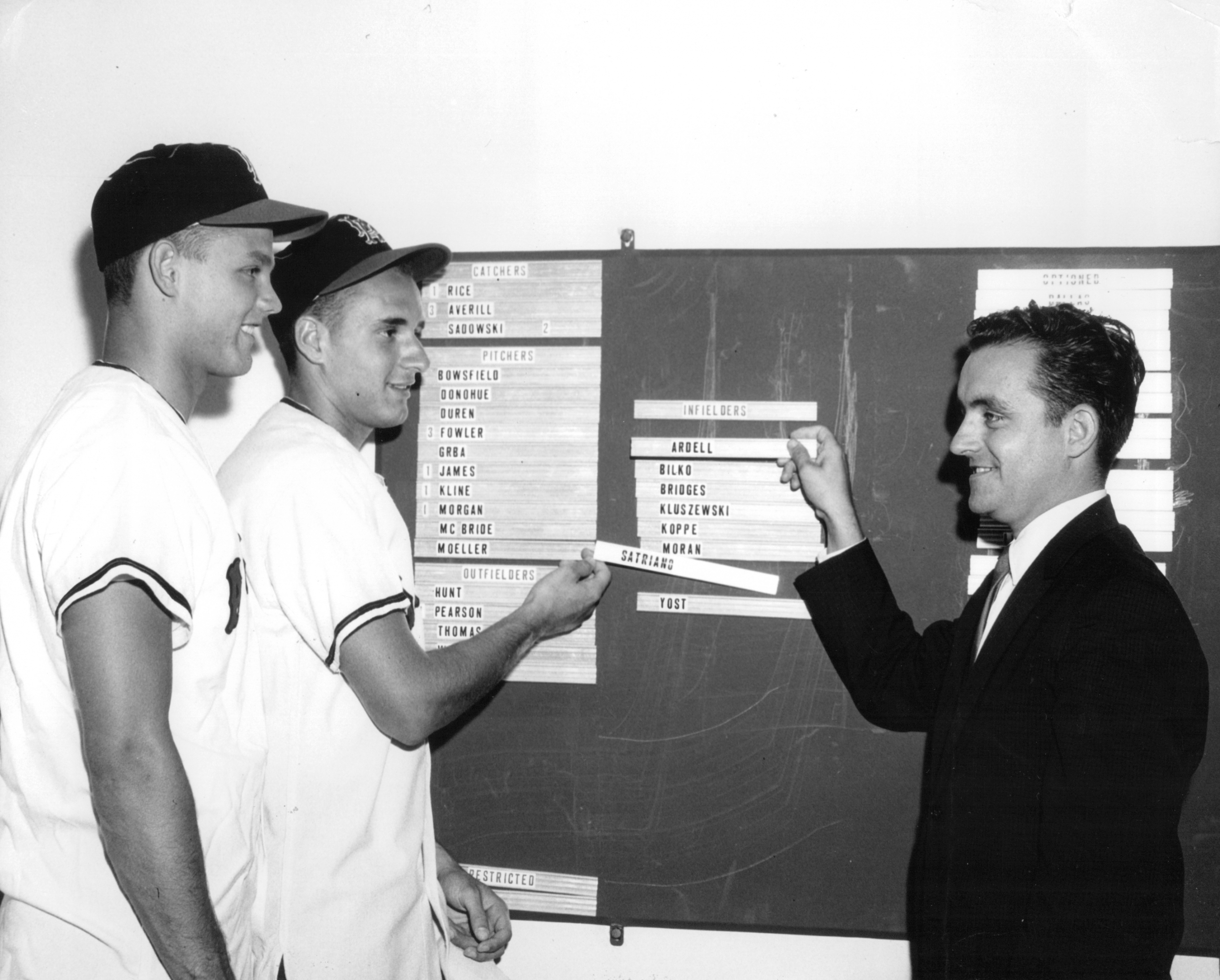

Roland Hemond joined the Los Angeles Angels’ on the ground floor in 1961, remaining with the Halos until 1970. Here is Hemond in 1961 with prospects Dan Ardell (l) and Tom Satriano (Courtesy of Angels Baseball)

Responding to six decades of demographic change, the National and American leagues moved to expand as the 1960s dawned. While the National League took a measured approach to analyzing markets, identifying ownership groups and giving them time to organize, the American League followed a stumbling, reactive path. One new franchise was given merely eight days to find personnel and plan for an expansion draft. And then, to conform to a Byzantine set of rules, the league president had to secretly revise the draft with a series of mandated trades before announcing the results.

The path to expansion for both leagues was a combination of new markets and old politics.

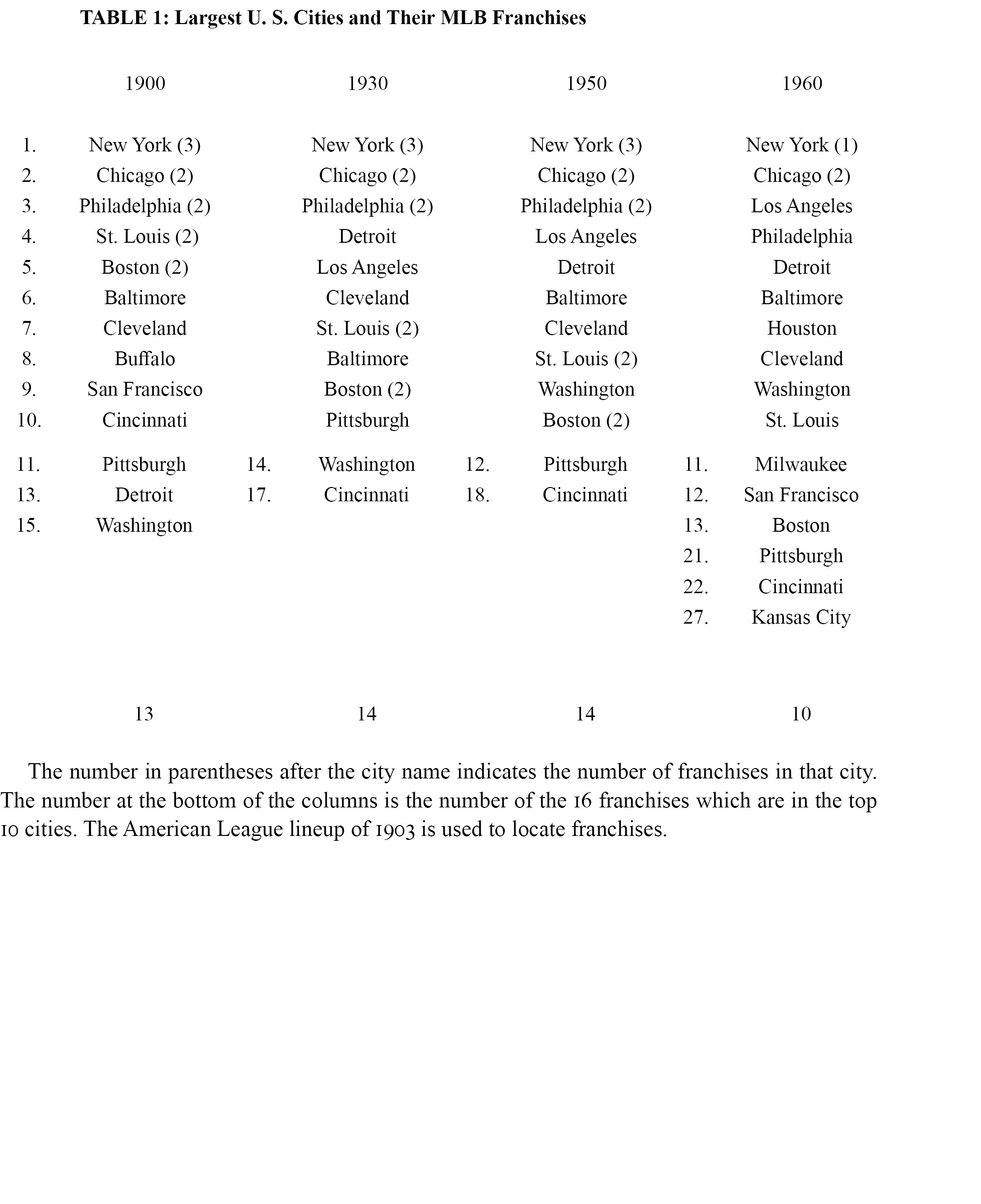

By 1953, the 50-year-old lineup of American and National League cities had been left in the demographic dust. Population had moved from the northeast quadrant to the vibrant cities of the West and South. The less financially successful clubs in two-team cities were finding it increasingly difficult to compete.

This situation was ameliorated with the moves of the Boston Braves to Milwaukee (1953), the St. Louis Browns to Baltimore (1954), and the Philadelphia Athletics to Kansas City (1955). But these shifts barely strayed from the Northeast. There was talk of further franchise shifts, or maybe expansion, but nothing actually happened. That pattern was shattered in late 1957 with the announcement that the National League’s New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers would move to San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The reaction in New York was swift. Within a few weeks, the Mayor’s Baseball Committee, headed by well-connected lawyer William Shea, was created to bring National League baseball back to the city.

The reaction in major-league baseball was slower. It wasn’t until December of 1958 that the owners formed the Major League Baseball Expansion Committee and it was here that the American League’s stumbles began.

For its representatives, the National League owners chose two powerful owners, Walter O’Malley of the Dodgers and Philip Wrigley of the Cubs. Wrigley was a well-connected, wealthy owner, who’d played a quiet role in the westward expansion of the National League. O’Malley was particularly important because the implicit assumption behind any expansion was that if the National League wanted back into New York, the American League would have to be allowed into Los Angeles

The American League owners chose Arnold Johnson, the man who had just moved his Athletics to the smallest market in major-league baseball, and George Medinger, a minority shareholder and a vice president of the Cleveland Indians. No Del Webb, whose Yankees were now the sole major-league team in New York. No Tom Yawkey.

Six months later, the expansion stew was complicated by the unveiling of Branch Rickey’s plan for a third major league to be called the Continental League. Rickey promised to respect major-league baseball’s player contracts, but he was clearly eyeing their best existing and potential markets. The Continental League loomed as a bigger threat as Rickey began to put together impressive ownership groups in major cities.

In New York, Shea was quickly won over to the Continental camp, and he brought with him Joan Payson, who’d been a minority owner of the Giants and bitterly regretted their move to San Francisco. Her brother was publisher of the New York Herald-Tribune and US Ambassador to Great Britain. Other old money quickly joined. There was Dwight Davis, Jr., whose father had funded tennis’ Davis Cup, and George Herbert Walker, a merchant banker with strong ties to the Harriman empire and the grandfather of eventual president George Herbert Walker Bush.

In Houston, it was all new money, but there was a lot of it. Craig Cullinan was Texaco. R.E. “Bob” Smith and “Bud” Adams had extensive oil and real estate interests in the Houston area. Roy Hofheinz was Smith’s partner in many ventures and a former mayor of Houston. The Denver group was headed by Bob Howsam, owner of the minor-league Denver Bears but with powerful political connections through his father-in-law, former Colorado governor and U.S. Senator Edwin C. Johnson. In Toronto, it was media mogul Jack Kent Cooke. In Minneapolis, Rickey rounded up members of the Dayton-Hudson department stores and Hamms Brewing families, as well as George Pillsbury.

Rickey’s Continental League would leave several legacies. It had coalesced viable ownership groups and educated them about dealing with major league baseball. And it had scared major league baseball.

In Washington, DC, Edwin C. Johnson’s connections had brought about legislation to limit the number of players major-league teams could keep under contract, and he had aided New York Representative Emanuel Celler’s antitrust hearings on baseball. In Houston, Bud Adams had struck fear into the hearts of the owners. In addition to his baseball interests, Adams was a major player in the creation of the American Football League. In 1960, his Houston Oilers drafted the Heisman Trophy winner from LSU – Billy Cannon. The Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League had offered Cannon $10,000. Adams offered $110,000 and the idea of competing for amateur talent with that kind of money reverberated through major-league baseball.1

In August 1960, the two leagues met and announced each would absorb two teams from the Continental League. While the National League immediately began to examine the potential markets and to interview the possible ownership groups, the American League owners argued over internal issues, such as existing teams’ desires to move and the possibility of ownership changes. Arnold Johnson had died that spring and other teams were thought to be on the market. The American League began its reactive spasms.

On October 10, Webb pushed the American League’s somnolent Expansion Committee into going after Houston.2 The next day, O’Malley announced the Houston Continental League group had applied for membership in the National League. Six days later, President Warren Giles announced Houston and New York, with its Continental League ownership group, would join the National League for the 1962 season.3

The 1960 census would soon show that the markets underserved by major-league baseball were New York, Los Angeles, and Houston. The National League was now in all three, the American in one. But, American League sources were sounding confident about the Dallas-Ft. Worth market, another growth area.4

A few days later, the American League revealed Calvin Griffith would be allowed to move his Washington Senators to Minneapolis-St. Paul and two expansion teams would be created in cities to be named.5 To one-up the National League, Webb said it might add another two teams by 1964 and that its expansion teams would start play in 1961, a year before the National League. These teams had no general managers, no managers, no players, no ticket sales department and a spring training that would begin in four months. Webb glossed over the fact that these moves broke the August agreement to choose ownership groups from the Continental League, a decision Rickey characterized as “the dictionary definition of perfidy.”6 The Sporting News and other commentators suggested the Americans’ pace was too headlong.

On November 17, 1960, American League president Joe Cronin announced that one of its expansion teams would replace the Senators in Washington and that it would petition major-league baseball to be allowed into the Los Angeles area.7 The promising market of Dallas-Ft. Worth fell out of the saddle. Cronin set the expansion draft for November 25. In those eight days, including a weekend and the Thanksgiving holiday, the league would have to resolve the Los Angeles situation. The Washington team would have eight days to prepare for the draft. The Los Angeles team, whose ownership group was not known, would have less.

November 25 passed with no resolution of the Los Angeles situation and no expansion draft. On November 28, the Senators lurched into life by taking Ray Semproch and John Gabler in the minor-league draft. The Los Angeles team didn’t participate because it didn’t exist yet.

By December 6, the AL had negotiated hastily with Walter O’Malley to get into Los Angeles and slapped together an ownership group headed by former country music star and radio/tv entrepreneur Gene Autry. Autry’s organization would have eight days to prepare for the December 14 draft and less than three months before spring training.

For the draft, the Los Angeles team would be aided by several factors. Autry quickly hired former Braves manager Fred Haney as general manager and recently dismissed Giants manager Bill Rigney as field manager. Both were familiar with many major-league players, although more heavily in the National League. Walter O’Malley ordered his staff to turn over the Dodgers’ scouting reports on American League minor leaguers. But the big prize was Los Angeles-area resident Casey Stengel, recently fired as New York Yankees manager and very miffed about it. Stengel gave Haney and Rigney a full rundown on Yankees minor leaguers.

So, on the chilly morning of December 14, Haney and Rigney from the Angels as well as manager Mickey Vernon, general manager Ed Doherty, and farm director Hal Keller of the Senators climbed to the sixth floor of the IBM Building in Boston, where President Joe Cronin kept the American League’s offices. Keeping the number of people in the room to six was designed to protect the secrecy of the players the existing eight teams had, or hadn’t, protected.

Those teams had been required to expose 15 players from their 40-man rosters. Seven of those players had to come from the roster as of August 31, 1960, just before the September callups of minor leaguers. As would a different set of rules by the National League a year later, the process maximized protection for the existing franchises and minimized quality for the expansion teams. Each player selected would cost $75,000.

As the Washington Senators’ 1961 media guide proclaimed, ‘A Team is Born,’ with general manager Ed Doherty, manager Mickey Vernon, and president Elwood ‘Pete’ Quesada (Courtesy of John Schleppi)

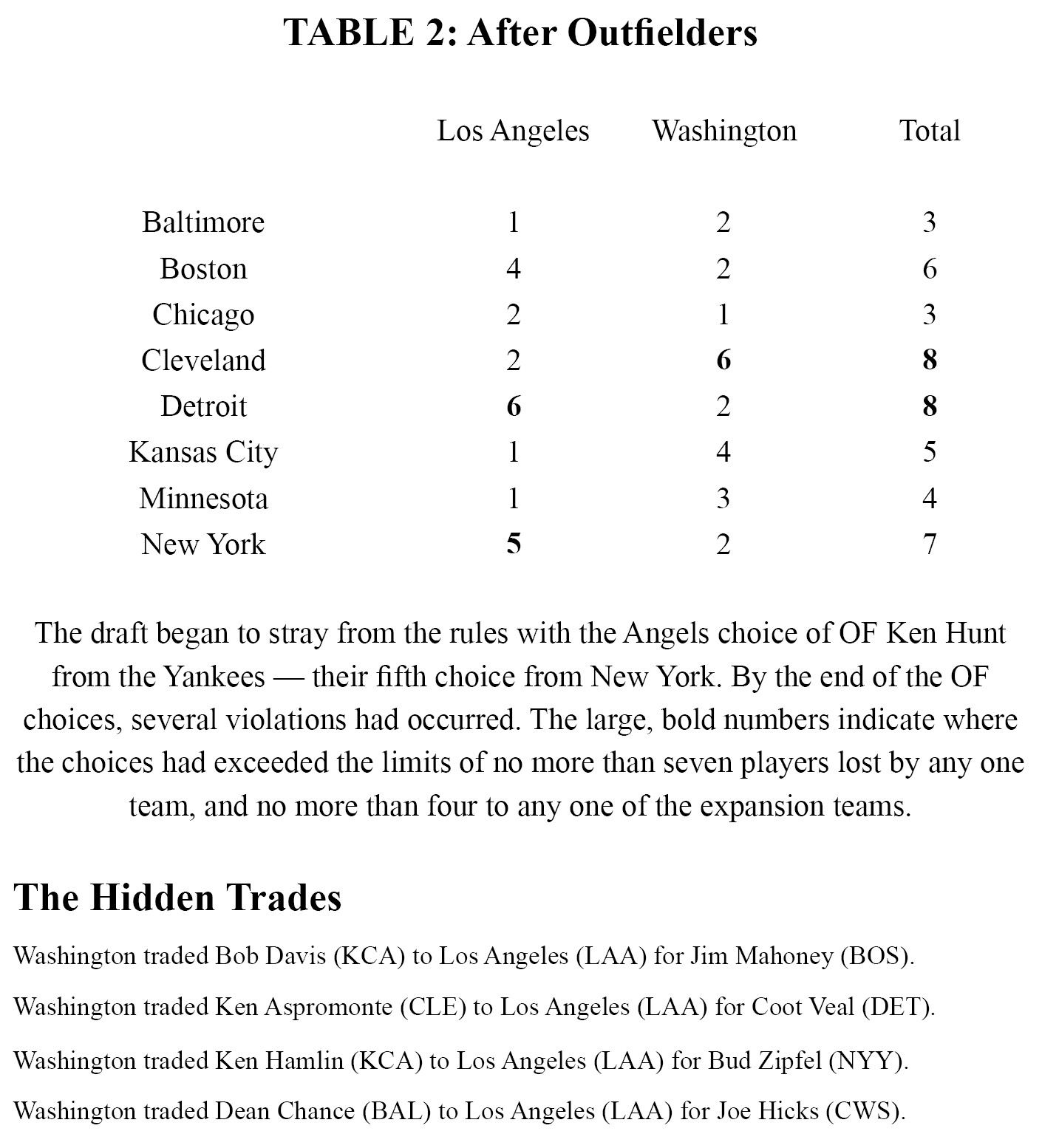

The league had created a complicated set of draft rules. Each team first had to select 10 pitchers, then two catchers, six infielders, four outfielders, and finally six players from those remaining. To make it even more complex, no existing team could lose more than seven players and no expansion team could take more than four players from any one existing team. Crucially, Bill Rigney recalled, the American League didn’t inform drafting teams of this rule.8

The pitching and catching selections went smoothly enough, starting with the Angels choosing Eli Grba and the Senators taking Bobby Shantz, both from the Yankees. But, with the 27th pick, the Angels took infielder Coot Veal from the Tigers. They already had selected pitchers Bobby Sprout and Aubrey Gatewood, catcher Bob Rodgers, and third baseman Eddie Yost from Detroit. Four picks was the limit in the rules and Veal took them over it.

Nobody at 540 Boylston Street raised a red flag. With the outfielder picks, things got really messy. With the 40th pick, the Angels took outfielder Ken Hunt from the Yankees, their fifth choice from New York. Four picks later, they took yet another Tiger – outfielder Neil Chrisley. Washington quickly joined the mess, taking Marty Keough and Jim King from Cleveland with the 41st and 43rd picks, giving them six picks from the Indians, in addition to the two taken by the Angels. The Indians and Tigers had now lost eight players and still nobody said, “Stop.”

With the miscellaneous players, the situation got worse. The Angels took their fifth players from both the Red Sox and White Sox while the Senators took their fifth from Baltimore and Kansas City. Finally, Cronin stepped in after the Angels took Julio Becquer from the Twins with the 55th and penultimate pick. He ordered Washington to drop catcher Red Wilson, one of their Indians’ picks, and, because of the inflexibility of the rules, replace him with another catcher – Pete Daley of Kansas City. While reducing the Senators’ Indians picks to five, this raised their Athletics selections to six. Cronin then had the Angels drop Neil Chrisley and take Faye Throneberry of the Twins. Then, Washington took its last regular pick, pitcher Rudy Hernandez from the Twins.

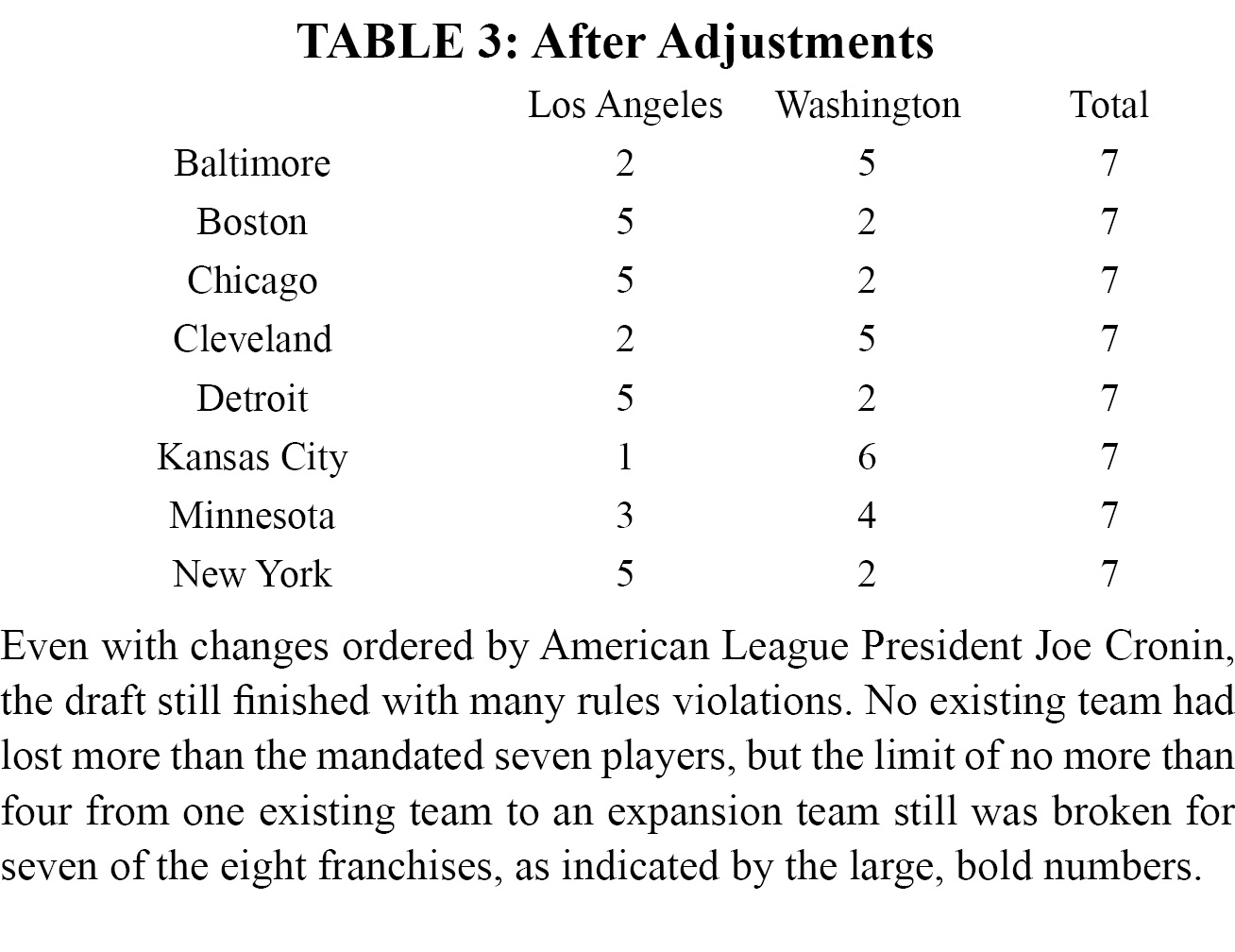

The scorecard now read: Boston, Detroit, Chicago, and New York had lost seven players, but five each were to the Angels; Boston and Cleveland had lost seven, but five to the Senators; Kansas City had lost seven but six were to Washington. Only the Twins losses were according to the rules.

Cronin now ordered trades to rectify the mistakes. To balance the Red Sox, the Senators sent pitcher Bob Davis of Kansas City to the Angels for Boston infielder Jim Mahoney. Cleveland and Detroit were evened out when the Angels shipped Coot Veal to the Senators for Cleveland infielder Ken Aspromonte. Kansas City and New York’s losses were brought into line with the rules when Washington traded infielders – Ken Hamlin to the Angels for Bud Zipfel.

One last trade was needed. The Senators had too many Orioles. The Angels had too many White Sox. Finally, with Cronin leaning in, the deal was struck. The Senators sent outfielder Joe Hicks to the Angels for a 19-year-old pitcher named Dean Chance who had spent the 1960 season at Fox Cities of the Three-I League. Hicks would have 389 more major-league plate appearances, batting .221. Dean Chance would win 20 games twice and a Cy Young Award.

Joe Cronin emerged from the draft and walked down Boylston Street to the Venetian Room of the Sheraton Plaza Hotel, where reporters awaited the results. He supplied each team’s list of 28 choices and acknowledged one small glitch when they found the Indians had lost eight players. This was an oblique reference to replacing Red Wilson with Pete Daley. Cronin did not mention the Throneberry for Chrisley switch nor the four trades that made the picks conform to the draft rules. Neither of the expansion franchises would win a postseason game until 1979, nor a postseason series until 2002.

ANDY MCCUE is a former president of SABR and winner of the 2007 Bob Davids Award. His Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion won the Seymour Medal for 2014. He’s a retired newspaper reporter, editor, and columnist.

ERIC THOMPSON is a two-time presenter at SABR national conventions concerning baseball’s first expansion between 1960 and 1962. A retired high school mathematics teacher and a lifelong Cleveland Indians fan, Thompson coached youth baseball and served as an assistant high school baseball coach for many years. Thompson played softball for nine years in The Babes of 1916 senior league for players 65 and over. Eric lives in Solon, Ohio, with Colleen, his wife for 50 years. He has three grown children and five grandchildren.

Sources

The material on the management of the expansion draft is available in the American League records at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and was confirmed by Hal Keller in a phone interview on October 30, 2010.

Notes

1 Michael Shapiro, Bottom of the Ninth (New York: Times Books, 2009), 193-4.

2 Ibid., 240-1.

3 Los Angeles Times, October 18, 1960: IV, 1.

4 Joe King, “N.L. Opening Door for Houston – Dallas Likely A.L. Addition.” The Sporting News, October 19, 1960: 6.

5 Los Angeles Times, October 27, 1960: IV, 1.

6 Roy Terrell, “The Damndest Mess Baseball Has Ever Seen,” Sports Illustrated, December 19, 1960: 18.

7 Los Angeles Times, November 18, 1960: IV, 1.

8 Tyler Kepner, “Expansion the Hard Way by 1961 Angels,” Press-Enterprise (Riverside, California), November 12, 1997.