Modern Baseball’s Greatest-Hitting Team: The 1930 Phillies’ Opponents

This article was written by Tom Ruane

This article was published in Fall 2009 Baseball Research Journal

What was the best-hitting team in modern (i.e,. post-1900) baseball history? There are many ways to answer that question. If you were to rank offense the way newspapers used to, by batting average, the 1930 Giants and their .319 batting average would top the list. That same year, the Phillies collected the most hits in a season, with 1,783, and the following summer the Yankees set a record, which still stands, when they crossed the plate 1,067 times.

But there was a “team” that scored almost a run per game more than the 1931 Yankees, that collected nearly 2,000 hits and whose .346 batting average far surpassed that of the Giants. They were the opponents of the 1930 Philadelphia Phillies.

Here are the top five teams in runs, hits, and batting average compared to the 1930 Anti-Phillies:

Table 1

| Year | Team | Runs |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | NY A | 1067 |

| 1936 | NY A | 1065 |

| 1930 | NY A | 1062 |

| 1950 | BOS A | 1027 |

| 1999 | CLE A | 1009 |

| 1930 | ^ PHI | 1199 |

| Year | Team | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | PHI N | 1783 |

| 1930 | NY N | 1769 |

| 1930 | STL N | 1732 |

| 1921 | DET A | 1723 |

| 1930 | CHI N | 1722 |

| 1930 | ^ PHI | 1994 |

| Year | Team | BAvg. |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | NY N | .319 |

| 1921 | DET A | .316 |

| 1930 | PHI N | .315 |

| 1930 | STL N | .314 |

| 1922 | STL A | .310 |

| 1930 | ^ PHI | .346 |

The difference between the first- and fifth-place teams in the chart above is 58 runs, 61 hits, and 9 batting-average points. The difference between the Phillies’ opponents and the top of the list are 132 runs, 211 hits, and 27 points.

So how did they do it? Well, they had three things going for them. First of all, they hit in a year when offense was at a historic high. Of the fifteen teams on the three lists above, seven are from 1930. And the 1930 Cubs finished fourth in the league that season in hits and still made the list. If the Cubs had gotten two more hits in 1930, the top four hit totals would all have been from the 1930 NL. The league that year amassed 13,260 hits; the second-highest total in a modern eight-team league was the 12,657 collected by the 1936 AL.

Second, they played half their games in Baker Bowl, a park that was extremely friendly to hitters. It had a short right-field fence—280.5 feet down the line and only 300 feet to right-center. The park’s dimensions didn’t result in that many more home runs, because of the 40-foot wall, featuring a huge ad for Lifebuoy soap (“which tells house ball players managed to be accepted socially after they are through with their daily excercise”), topped by another 15-foot wire screen. What they did increase, however, were singles and doubles. Here are the records of Philadelphia and their opponents both at Baker Bowl and elsewhere that year:

Table 2

| AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | BB | BAVG | SLG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 5789 | 1187 | 2034 | 446 | 28 | 144 | 503 | .351 | .513 |

| Away | 5642 | 956 | 1743 | 299 | 97 | 124 | 490 | .309 | .462 |

According to the Chicago Tribune in 1937:

The right fielder who plays most of his games at Baker bowl has a better chance . . . to make assists than any outfielder on any other team in the National league. But he had a hard time building up his record for catching line drives. He must play with the seat of his bloomers against the soap ad and his main job is to judge bounces off the soap.1

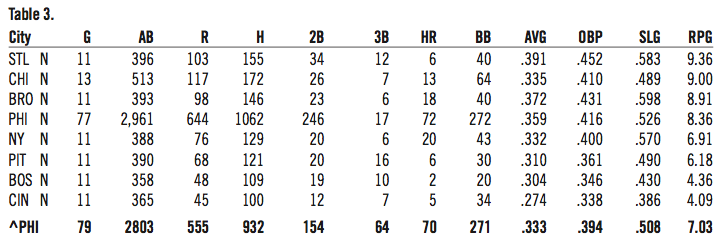

Still, had the Phillies’ opponents that year played all their games away from Baker Bowl, they still would have broken the record for most runs, hits, and highest batting average in a season. Here’s what they did in each city (see table 3).

(Click image to enlarge.)

The last line is the sum of all the non-Philadelphia totals. Expanded to a full season, that would have resulted in 1,096 runs and 1,840 hits, which, along with the .333 batting average, would have still broken all three team records.

The third thing this team had going for it was the good fortune to face perhaps the worst pitching staff in modern major-league history. Not that bad pitching staffs were anything new to Phillies fans. Bad pitching and the Phillies had been synonymous for years—ever since December 11, 1917, to be exact. On that date, owner William Baker sent Pete Alexander, who had just completed his third successive 30-win season, along with his starting catcher to the Cubs for Pickles Dillhoefer, a .126-hitting scrub catcher; Mike Prendergast, a 3–6 pitcher; and $55,000. What followed was the National League’s version of the Curse of the Babe, as the Phillies went from having the second-best pitching staff in 1917 to allowing the most runs per game in 1918.

And it didn’t stop there. In what could be the single greatest domination of any statistical category, the Phillies’ pitchers kept right on allowing the most runs per game year after year until their string was finally stopped by the 1940 Pirates. Think about it: With all the great-hitting teams the New York Yankees had throughout the years, they never led their league in runs per game more than four years in a row. Phillies’ pitchers led their league in allowing the most runs per game for 23 consecutive years.

Baker Bowl was home of the Philadelphia Phillies from 1887 to 1938. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

As they entered the 1930 season, Philadelphia was twelve years into that record run. The 1929 staff had outdone themselves, setting a modern single-season record for most runs allowed. At the start of 1930, here were the top ten runs-allowed totals in modern major-league history:

Table 4

| Year | Team | Runs |

|---|---|---|

| 1929 | PHI N | 1032 |

| 1911 | BOS N | 1021 |

| 1923 | PHI N | 1008 |

| 1928 | PHI N | 957 |

| 1925 | PHI N | 930 |

| 1929 | DET A | 928 |

| 1925 | BOS A | 922 |

| 1922 | PHI N | 920 |

| 1921 | PHI N | 919 |

| 1925 | STL A | 906 |

If it hadn’t been for the 1911 Boston Braves, the Phillies would have set the record for most runs allowed four times during the 1920s.

So what moves were made after the 1929 season to improve their pitching staff? The only one of consequence was to try to bury “The Curse of Old Pete” by bringing back Alexander in a trade with the Cardinals twelve years to the day after he had been traded away to the Cubs. He turned 43 years old before opening day and was coming off a turbulent, 9–8 season with the Cards. They kept the rest of their record-setting pitching staff pretty much intact.

Despite this, there was hope going into the season. They had won 71 games in 1929, their highest total since the original Alexander deal, ending up in fifth place. Moreover, they finished strongly. From August 14 to the end of the season, they had gone 30–18, the best record in the league.

Spring training in 1930 was an unusually rainy one, but the team left Winter Haven, Florida, and headed north with a great deal of optimism—or, as James Isaminger of The Sporting News put it, “Shotton and his Phillies face the barrier with the feeling that scarcely any position in the percentage table is beyond their reach.”2

Seldom has an opening-day game given a more misleading indication of things to come than the Phillies’ 1–0 victory over the Brooklyn Robins on April 15. According to Isaminger, Les Sweetland’s three-hit shutout “belied the current Spring fiction that Burt Shotton has no dependable pitchers.”3

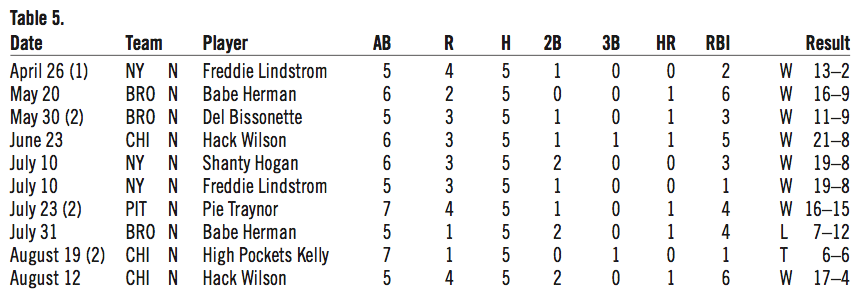

On April 23, the sixth game of the season and the second in Baker Bowl, the Phillies scored two ninth-inning runs to defeat the Robins 16–15. This would be the first of 45 games in which Phillies’ opponents would score in double digits. In the next game, a 13–2 Giant victory, Freddie Lindstrom became the first Phillies opponent to rap five hits in a game. He would not be last. They are listed in table 5.

(Click image to enlarge.)

A modern major-league record (since broken) of 19 extra-base hits by both teams was set May 7 in the Cardinals’ 16–11 victory. Chick Hafey knocked in 5 runs in one inning, ending the day only a single shy of hitting for the cycle. On August 21, he’d correct that oversight during a 16–6 romp and join Hack Wilson (on June 23 — see the chart above) as the second player to hit for the cycle against the Phillies that year. Once again, he’d drive in 5 runs.

After the Phillies dropped their sixth straight game on May 8, Isaminger wrote, “It’s the old trouble with a daily example of slovenly pitching to nullify the batting power of a team, but flinging is as much a part of baseball as anything else and a team not equipped with pitching strength never can hope to get anywhere no matter how they boast about their battles.”4

In other words, the spring “fiction” had become fact.

Benny Frey, rookie pitcher for the Reds, ran his record to 4–0 with a 5–4 victory over the Phillies on May 11. Pete Alexander was his mound opponent, making his last major-league start. He gave up eight hits in less than four innings and would make his last appearance on May 28 in a mop-up role against the Braves.

On Memorial Day, Brooklyn swept the Phils in a doubleheader at Ebbets Field, by scores of 11–1 and 11–9. In the opening contest, Del Bissonette hit a home run only to be called out for passing Babe Herman on the basepaths. He was credited with a single instead, but he made up for his blunder by rapping out five successive hits in the second game.

On June 2 the Phillies (“badly bent of late,” according to Isaminger)5 opened a lengthy homestand, which midway was interrupted for a Sunday jaunt to Cincinnati to play a doubleheader. This was a way schedule makers got around the Pennsylvania blue laws against Sunday baseball, the Dodgers and the Giants being the Phillies’ more common Sunday opponents.

One of the Phillies’ few losses during their stay at Baker Bowl was the Cardinals’ 11–10 victory on June 3. Syl Johnson was the winning pitcher despite giving up 20 hits and 9 runs in 8 1/3 innings. In the Pirates 19–12 victory in the opening game of the June 14 doubleheader, Pie Traynor may have tied a record for the most RBIs in a game without an extra-base hit when he drove home seven runs with three singles. During the years covered by Retrosheet’s box scores, only Jack Fournier and Tracy Jones managed to do this as well, Fournier on July 2, 1925, and Jones on June 9, 1989. Two days later, in a game that The Sporting News described as “wild and woolly,” the Phillies built up a 16–3 lead over the Pirates before hanging on for an 18–14 decision.6

Heading west, the Phillies dropped three of four to the Cardinals before being ambushed by the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field, as the Cubs racked up 40 runs in three games, highlighted by a 21–8 pounding in the first game. In the finale, a 13–12 slugfest, Kiki Cuyler and Gabby Hartnett combined for three home runs and 11 RBIs. The Cubs were in the middle of a 20–7 June run that would land them in first place, while the Phillies were simply dropping three more games on their way to their third 17–60 road record in four years.

The next day, the Phillies demonstrated they could lose low-scoring games as well, falling 1–0 to the Pirates. The only run scored when, with a man on third, Phil Collins dropped the ball during his windup. After the road trip, the Phillies had five days off before their next scheduled game. The Sporting News called it the “longest mid-season voluntary lay-off in history,”7 and it occurred because a series with the Reds, originally scheduled for the end of June, had been cancelled and the games moved to create three additional Sunday doubleheaders. During this extended holiday, they attempted to shore up their pitching staff by purchasing Snipe Hansen from the Richmond Roses of the Class B Central League. After winning 11 games (and walking more than 100 batters) in two months for Richmond, Hansen would go 0–7 for the Phils.

All but six of their 33 games during the month of July were played at Baker Bowl. The Phillies won only eight of them, cementing their hold on last place. The frustration of their fans reached its height on July 23 and 24, when their team scored 15 runs twice, in back-to-back games, only to lose them both, by scores of 16–15 and 19–15.

Their opponents scored in double digits twelve times during the month (“huge gobs of runs,” according to Isaminger)8 and only twice were held to less than a hit an inning. Included in this month were games described by The Sporting News as “a slugging orgy” (July 7, 13–12 Giants), “a thorough beating” (July 10, 19–8 Giants), “a dizzy slugfest” (July 17, 14–9 Reds), and another “wild and woolly game” (July 24, 19–15 Cubs).9 A 16–2 Cubs victory on July 26 featured three home runs by Hack Wilson, bringing his season total to 32.

In early August, the Phillies departed on a road trip that would take up most of the month. The trip featured some of the best pitching of the year, as the staff extended to 21 straight games (the first three of them were in late July) in which they held their opponents to less than ten runs. The road trip included a string of twelve games in which the Phillies allowed an average of less than four runs a game. Not surprisingly, this streak coincided with trips to Boston and Cincinnati, by far the two weakest-hitting teams in the league.

By the time they reached Wrigley Field in mid-August, things had returned to normal. That seven-game series included 10–9, 17–3, 9–8, and 10–8 scores, Hack Wilson’s 43rd home run (tying an NL record) of the season, and a fight, between Philly pitcher Hap Collard and his catcher, over who’d been responsible for a recent rally. Hack’s home run was hit over the head of Chuck Klein, Philadelphia’s right fielder and the man whose record he’d tied. Chuck saluted Hack as he rounded first base and was given an ovation from the Wrigley fans for his display of good sportsmanship. From there, it was on to St. Louis, where the Cards averaged 10 runs a game in sweeping a fivegame series.

They returned to Baker Bowl near the end of August with a record of 40–83, 13 1/2 games out of seventh place. All but six of their remaining games would be played at home. One of their brief trips away was to Ebbets Field for a Sunday game on August 31, where they lost 14–3 to the Robins in the first game ever played with a new 20-foot screen installed in right-field to reduce the number of cheap home runs. Modeled after the screen at the Baker Bowl, in this game it did not have the desired effect, as the two teams combined for five home runs.

Returning six days later, the Phillies were clobbered once again, this time 22–8, in a game that featured another five home runs. The 22 runs were the most scored against Philly pitchers in 1930 and followed an 18–5 defeat at the hands of the Giants, who were led by Bill Terry’s seven RBIs. Freddie Fitzsimmons and Dolf Luque, the pitchers benefiting from all this offense, both pitched complete games despite giving up a combined 13 runs and 28 hits, including 12 doubles. Luque went the distance in his six starts against the Phillies in 1930, winning them all despite giving up an average of more than 11 hits and 5 runs a game. His teammates supported him in these games with 80 runs, ensuring that he wouldn’t have to pitch too carefully.

The Phillies then took a brief break from high-scoring games, as they traveled to Boston and split a doubleheader with the Braves, winning 1–0 and losing 2–1. The losing pitchers allowed only two and five hits, respectively. But rather than signaling a late-season pitching resurgence, these games were simply an anomaly that wouldn’t be repeated. Over the final 20 games, Phillies’ opponents would be held to fewer than 10 hits only once (when the Pirates needed only 8 to defeat them 6–5 on September 18) and would post a .383 batting average during the month of September.

In early September, the Phillies took advantage of some off-days to play their first two night games, exhibitions against Allentown (Eastern League) and Baltimore (International League). Although losing to the Allentown Buffaloes 7–5, the Phillies managed to beat the Orioles 9–6 in ten innings, despite a three-run home run by Joe Hauser, who’d finish the year with 63 homers (not counting the one hit in this game), a record for Organized Baseball. It stood until he broke it three years later (with 69) while playing for the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association.

Down the final stretch, Phillies’ opponents averaged more than 10 runs per game over a 12-game span, starting September 12 with a 17–4 romp at the hands of the Cubs, highlighted by Hack Wilson’s five hits (including his 49th home run). Before coming to Baker Bowl, the Cubs had scored only a single run in three straight losses to the Robins. They scored 39 in their four games in Philadelphia, managed only a series split (including a thrilling 12–11 loss), and dropped out of first place for good.

The Pirates came into town next and won two of three, their only loss being by the score of 15–14 in ten innings. This was yet another game described by The Sporting News as “wild and woolly.”10 They seemed to be running out of ways to describe games in which the losing team scored in double digits. The Phillies would drop nine such contests over the course of the year.

The Phillies missed out on an opportunity to play spoiler when first-place St. Louis followed the Pirates into Baker Bowl. The Cardinals took four of five games, the final two by scores of 15–7 and 19–16. That last one was witnessed by Connie Mack and his Athletics, who were taking advantage of an offday to scout their likely World Series opponent. According to The Sporting News, they “left Baker Bowl somewhat confused as to whether they must play baseball or cricket in the World Series.”11 The Cards scored more runs in that game than they would in all six games of the World Series.

Five days later, the season came to a merciful close in the Polo Grounds with the Giants taking a 7–6 ten-inning affair.

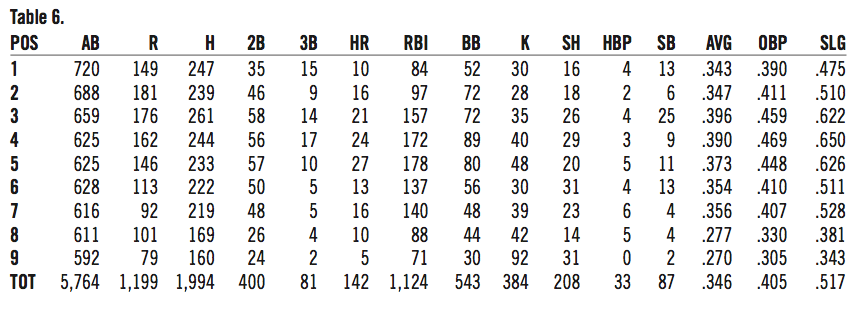

Philadelphia’s opponents came within a single run (Del Bissonette’s lost home run on Memorial Day) of scoring 1,200 runs. Table 6 shows what this team did by batting-order position.

(Click image to enlarge.)

If this had been an actual team (and if the regulars never left the lineup), the first three batters would have set modern records for at-bats, runs, and hits, respectively. The fifth-place hitter’s 178 RBIs would have set the major-league record if Hack Wilson (aided by his 38 RBIs in 24 games against the Philly pitchers) hadn’t knocked in 191 that season. They produced so many hits that the seventh-place hitter’s 219 hits would have been bettered by six of his teammates. The lineup didn’t feature a lot of home runs by modern standards, but their 140 home runs had been topped by only one other National League team, the 1929 Phillies. In addition to setting modern team records for runs, hits, and batting average, this squad would have also owned the marks for most doubles and highest slugging percentage.

It’s a little surprising that the eighth-place hitter, preceded by five batters averaging .374 and more than 50 doubles, hit .277 and yet knocked in only 88 runs. By comparison, Sam Mele of the Senators had a similar year in 1951 (.274 average, 153 hits, and 5 home runs) and had 94 RBIs in the middle of a lineup that boasted one .300-hitter and a .263 team batting average.

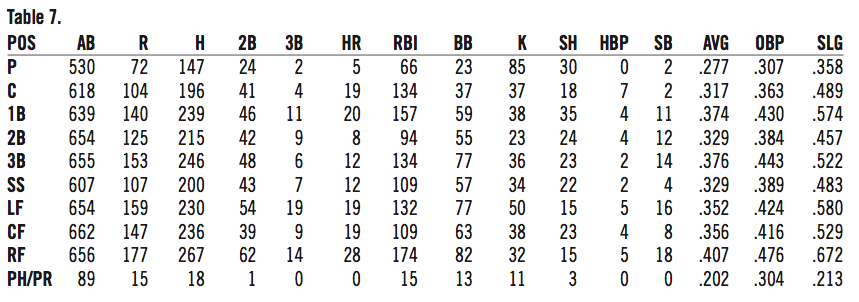

Table 7 shows how they hit by defensive position.

(Click image to enlarge.)

The right-fielder’s stats stand out the most and he would have set modern NL marks for most runs, hits, and doubles, but all the regulars in the lineup except the pitcher would have hit over .300 and scored more than 100 runs, and all but one of them would have more than 40 doubles and 100 RBIs. I was a little surprised at how poorly the pinch-hitters did, with an OPS just slightly over .500 in 89 at-bats.

To get some idea of how much of this was caused by Baker Bowl, table 8 shows how the Phillies’ opponents did there by batting-order position.

(Click image to enlarge.)

So who were these guys? Forty-four players that year had 60 or more at-bats against the Phillies. Their median batting average and slugging percentage were .379 and .564. This included two with batting averages over .500 and 14 players who hit better than .400. Table 9 shows who they were.

(Click image to enlarge.)

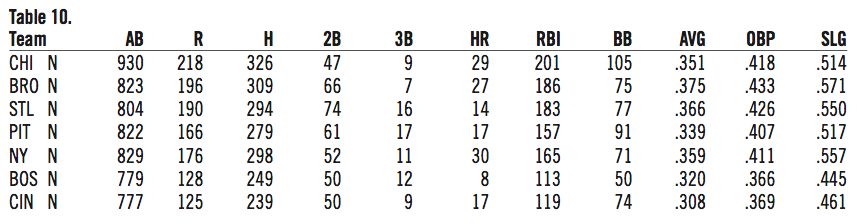

Table 10 shows how each team hit against the Phillies that season.

(Click image to enlarge.)

The 218 runs scored by the Cubs set a modern major-league record for most runs scored by one team against another in a season. At the time, Brooklyn’s 196 and St. Louis’s 190 were the second- and third-highest totals. (They have since been superseded by the 207 runs scored by the 1931 Yankees against the White Sox and the 216 runs scored by the 1950 Red Sox against the Browns.) Every team scored at least 1.5 more runs a game (and hit at least thirty points higher) against the Philadelphia pitching staff than they did against the rest of the league.

Fourteen different pitchers took the mound for the Phillies in 1930. Table 11 shows a capsule summary of the worst pitching staff ever assembled.

(Click image to enlarge.)

As bad as the starting pitching was (42–86 with a 6.15 ERA in 991 1/3 innings), the relief pitching was even worse. In 383 1/3 innings, the Phillies gave new meaning to the word relief by allowing 415 runs and 347 earned runs, for an 8.15 ERA.

This was not simply a bad pitching staff; it was one with very little promise of getting better. No pitcher under the age of 28 won more than a single game. With Alexander as the obvious exception, and he made only a brief appearance that year, none of these pitchers had accomplished much in previous seasons. Among the pitchers not named Pete, Claude Willoughby entered the season with a staff-leading lifetime victories, and only Phil Collins (10–7) had a winning record. Even their nicknames gave comfort to the enemy, led by Fidgety Phil Collins and Weeping Willie Willoughby, who was also known as Flunky.12

Despite his nickname, Collins was clearly the ace of the staff. At one point in late July, he was 10–3 while the rest of his teammates were 21–53. Imagine what the season could have looked like if he didn’t have the best year of his career in 1930.

Although just 1–9 as a starter, Hal Elliott finished 5–2 in relief, only two behind the Giants’ Joe Heving’s league-leading seven relief victories. This was quite an accomplishment for Hal in light of his relief ERA of 7.99. He should not be confused with Jumbo Elliott, who came to the Phillies during the offseason and ended 1931 tied for the NL lead in victories with 19. Jumbo weighed at least 65 pounds more than Hal and in half of the next season won as many games as Hal did in his entire career. Jumbo did follow Hal’s example, however, to lead the league in games pitched in 1931, perhaps the only time two different teammates with the same last name have led the league in the same pitching category in consecutive years.

Chet Nichols was a holdout in 1930, after getting drafted from Montreal of the International League. He had previously pitched ineffectively in trials with the Pirates and Giants and fared little better once he finally showed up for work in Philadelphia. His son, born after the 1930 season, would become the youngest pitcher in the modern era to lead a league in ERA when, in 1951 at the age of 20, he posted a 2.88 ERA. His final career ERA of 3.64 would be roughly half that of his father.

After the season, the Phillies made some moves to bolster their pitching staff, dumping Les Sweetland and Claude Willoughby, while trading Lefty O’Doul and Fresco Thompson to Brooklyn for Elliott, Clise Dudley, outfielder Hal Lee, and (as usual with Philly deals during the Baker era) a pile of cash.

In 1931, the Phillies once again allowed the most runs in the National League, but the total was only 828, a drop of 271 runs from the previous year. Jumbo Elliott’s good showing was one reason for the improvement, as was the best year of Ray Benge’s career, but a larger reason would be the drastic decline in scoring throughout the league. Something happened during the winter of 1930–31. Whatever had been done (and, of course, no one was admitting anything) before 1929 to boost offense had been undone by the time 1931 rolled around. After scoring a combined 11.4 runs a game in 1930, National League teams would see that total drop nearly 2.5 runs a game, to 9.0, the largest single-season scoring decline in modern history.

The Phillies wouldn’t allow more than 900 runs in a season again. William Baker sold the team in 1931, and they moved out of Baker Bowl in the middle of the 1938 season. By the late 1940s, they would start to assemble a strong pitching staff, and in 1950, led by Robin Roberts, Jim Konstanty, and Curt Simmons, the Phillies’ pitching staff would allow the fewest runs in the league for the first time since the 1915 pennant winners. They would also reach the World Series, losing in four games to the Yankees a little less than a month before Pete Alexander, whose trade coincided with the start of their long decline, died in St. Paul, Nebraska, at the age of 63.

TOM RUANE, a frequent contributor to the “Baseball Research Journal”, is director of Retrosheet.

Author’s note

A version of this article is posted at www.retrosheet.org. Retrosheet has box scores for every game played in the National League in 1930. This information was used extensively in this article and would not exist without the work of several volunteers, including Dave Lamoureaux, Wade Coble, Ron Carron, Jack Myers, Tom Bradley, Joe Murphy, and Steve Vetere.

Notes

1 Edward Burns, “Introducing Baker Bowl and That Short Right Field Fence,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 13 June 1938, A2. The earlier quote also came from this article, which was part of a series designed to persuade Cubs and White Sox fans to appreciate their home parks.

2 James C. Isaminger, “A’s Break Camp at Fort Myers; Six of Mack’s Rookies Make Good,” The Sporting News, 3 April 1930, 1.

3 James C. Isaminger, “It’ll Be Long Time Before Philly Fans Forget Al Simmons’ Debut,” The Sporting News, 24 April 1930, 1.

4 James C. Isaminger, “Champion A’s Run True to Form in A.L.,” The Sporting News, 15 May 1930, 1.

5 James C. Isaminger, “A’s Regain Winning Ways of Balmy Days,” The Sporting News, 5 June 1930, 1.

6 The Sporting News, 19 June 1930, 7.

7 James C. Isaminger, “When A’s Speed Up, Rivals Step on Gas,” The Sporting News, 10 July 1930, 1.

8 James C. Isaminger, “Macks Say It with Big Innings, As They Did in World Series,” The Sporting News, 24 July 1930, 1.

9 The Sporting News, 10 July 1930, 7; 17 July 1930, 7; 24 July 1930, 7; and 31 July 1930, 7.

10 The Sporting News, 25 September 1930, 7.

11 The Sporting News, 2 October 1930, 7.

12 These nicknames were taken from The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan, Information Concepts, 1969). I have always wondered just how many of the nicknames included in the book were actually ever used to refer to the players in question, at least while they were in earshot.