Montréal and Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Marcel Dugas

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

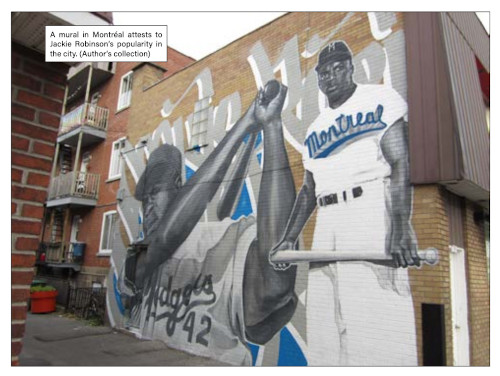

A mural in Montréal attests to Jackie Robinson’s popularity in the city. (Author’s collection)

“To the large group of Louisville fans who came here with their team, it may be a lesson of goodwill among men. That it’s the man and not his color, race or creed. They couldn’t fail to tell others down South of the ‘riots,’ the chasing of a Negro – not because of hate but because of love.” — Sam Maltin, Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1946.

In books and documentaries on the topic, it’s generally misquoted along the lines of “It was the first time in history that a White mob chased a Black man with love, instead of lynching, on its mind.” But this is the actual quote from Sam Maltin, the only reporter to describe what happened just outside Montréal’s Delorimier Stadium on the evening of October 4, 1946. On that day, Jack Roosevelt “Jackie” Robinson, 27-year-old second baseman of the Triple-A Montréal Royals, was chased down for almost three street blocks by hundreds of delirious Montréal baseball cranks.

They had just seen their Royals clinch the Junior World Series, earning the title of best minor-league team in North America. The crowd had asked — and received — curtain calls from team manager Clay Hopper and Curt Davis, the winning pitcher of the sixth and decisive game of the series. But the man they really wanted to cheer was the rookie infielder who had been the talk of the town (and the baseball world) that season, when he became the first Black player to compete in “organized” (a.k.a. White) baseball in the twentieth century.

They cheered and cheered and cheered, and when Robinson agreed to come out of the dressing room to receive the adulation of the fans, he had tears in his eyes. “He could never have imagined that a Black man could be treated that way by white people,” opined one reporter.1

Montréalers had fallen in love with Jackie Robinson to such an extent that they were not satisfied with a simple postgame tip of the cap. Two hundred fans were crowding the ballpark’s hallways after the game to touch him, to wish him well, to shake his hand. Robinson had to channel his football-playing days to find a way out of the building. Outside, another 500 or so baseball-loving Montréalers were waiting for him. He had to run until he could jump into a moving car that took him away from his admirers.2

The atmosphere was quite different 346 days earlier when Robinson first set foot in what was then Canada’s metropolis. Royals President Hector Racine had touted on October 23, 1945, an announcement that would “revolutionize the baseball world,”3 which led some to believe that Montréal would be awarded a major-league franchise. The signing of a then almost completely unknown infielder from California felt like a dud to Montréalers. “Local sports fans didn’t seem to appreciate how monumental and revolutionary a move the Brooklyn and Montréal ball clubs made . … ‘So that’s what it is,’ they said, obviously let down. ‘What’s so big about that?,’” wrote veteran reporter Dink Carroll in his column.4

If fans did not immediately grasp the magnitude of the moment, newspapermen were quick to point out that that “epoch-making event”5 constituted “perhaps the biggest news in the history of organized baseball.”6 Although one journalist noted that “when Robinson was presented to sports reporters, only three of them shook his hand while others were indifferent or left the room where the announcement was taking place and that attitude can be considered as being quite revealing.”7

Two months earlier, Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey had sent right-hand man and former Royals manager Clyde Sukeforth to Chicago to watch Robinson in action and bring him back to Brooklyn. After years of patient scouting, Rickey was ready to tap Robinson as the standard-bearer of his “great experiment” of baseball integration. The now famous “I want a man with enough guts not to fight back” meeting between the two concluded with a promise that Jackie would be signed by the Dodgers’ top farm team before November 1.8

After two years of a rather unsuccessful affiliation with the Pittsburgh Pirates, the Royals joined Brooklyn’s chain before the 1939 season. Even though the Dodgers’ 21-team farm system included another Triple-A club, the International League’s Royals were generally considered to be on top of the heap. Robinson was offered to the Royals, and the national pastime of the United States wound up being integrated by a Canadian club.

Even though on the day of the contract signing, reporters mentioned some of the obstacles Robinson would be facing during the season (hostility from fans, pitchers throwing at his head, being turned away by hotels, etc.), no one seemed to doubt that he would be treated well in Montréal. The city had a long history of having Whites and Blacks on the same ball fields. Montréal had been a frequent stop for African American barnstorming clubs going back to at least 1896.9 Entire teams of Black players had competed in local and provincial leagues throughout the 1920s and 1930s. But Robinson did not simply receive the support of the fan base on the field. He was thoroughly embraced by the community as a whole.

The months that separated Robinson’s first visit to Montréal (for the contract signing) and his first game in town were a whirlwind. He married his longtime fiancée Rachel Isum. He was the subject of all sorts of speculation. Many observers thought he would be out of his depth in Triple-A baseball, if he got to play there at all. Rumors were flying left and right that he might not be allowed to play in the International League.10

The new Mrs. Robinson was the only wife allowed to attend spring training in the Royals camp. Branch Rickey must have felt that his pioneering ballplayer would need the emotional support, and he was prescient. Training camp proved to be a nightmare for the Robinsons and John Wright, a right-handed pitcher from New Orleans and former member of the Homestead Grays, who signed with the club in January.11

The Robinsons had a rough time getting from California to Florida. They were bumped from two planes because of the color of their skin, and could not find decent accommodation while they were waiting to be allowed onto another plane. They ended up making a long ride in the overcrowded back of a segregated bus to reach the site of spring training. And the horrible trip was only the beginning.

The Royals held their training camp in Daytona Beach, a city considered to be fairly liberal by the standards of the time. But players first went to the city of Sanford, Florida, for pre-camp. The Robinsons and Wright had barely reached Sanford when they literally had to flee the town, where significant resistance to the idea of integrated competition was building. When asked by Roger Kahn if the African American members of the Royals risked lynching had they stayed in Sanford, Rickey replied, “From reports that reached me, that was not entirely beyond the realm of possibility.”12

Robinson did not have to fear for his life after being repatriated to Daytona Beach. But he still had to earn a roster spot with the club, in an environment that was rife with distractions. A natural shortstop, he had to learn to play second base, at the same time battling arm issues. He struggled at the plate, assessing his own performance by saying he “specialized in pop flies to shortstop” early that spring.13 He also turned down a lucrative offer to play in the Mexican League.14

The hotel that lodged the Royals did not welcome Black patrons, so the Robinsons lived at a private residence in the African American part of town. Robinson and Wright’s presence caused the cancellation of seven exhibition games, and Robinson was pulled from a preseason contest when local police threatened to stop the proceedings if the Royals insisted on having an integrated lineup. Despite all this, and despite the many sleepless nights he endured,15 Robinson ended up going north with the club.

Before being introduced to his new fans, the Royals second baseman (and his teammates) went on a 12-game, four-city road trip. He integrated Organized Baseball in style on April 1 8 , 1946. He was the undisputed star of Opening Day in Jersey City, going 4-for-5 with a home run, four runs batted in, and four runs scored, as Montréal crushed the local Giants, 14-1.

But while the crowds and the opposing teams in both Jersey City and Newark proved easy to handle, things were quite different in Syracuse and Baltimore. The Maryland city was the league’s southernmost, and Robinson must have felt as if he had ventured into the heart of the Old Confederacy. Despite the presence of thousands of African American fans at the ballpark, the level of vitriol to which he was subjected was extraordinary.16 As for Syracuse, the fans did not cause major trouble. But the Chiefs players rode Robinson harder than any team in the league all season long.17

After having experienced all this, the Royals’ new number 9 must have felt a great sense of relief when the club’s plane touched down at Montréal’s Dorval airport on April 30, 1946, on the eve of the home opener. He was also, one would think, glad to realize that he didn’t have to win the crowd over. The publicity that surrounded his signing, the trials and tribulations of camp, and the remarkable performance he had given during the first road trip of the season earned him “possibly the nicest ovation ever given to a player in Montréal” on May 1.18

Robinson even received a bigger hand from the crowd than did his double-play partner Stan Bréard, a young man the Royals had plucked from the local sandlots. The Pittsburgh Courier’s Wendell Smith went further, saying that Montréalers gave the rookie an ovation that was heard “throughout the British Empire and most of its dominions beyond the seas.”19

Robinson did not deliver as memorable a performance in his Montréal debut as he had in Jersey City 13 days earlier. But as soon as the game was over, he was surrounded by loving fans. He eventually left the ballpark through a side door, with the assistance of two police officers. Even Rachel was assailed by admirers, and had to sign program after program.20 Thirteen games into his Royals career, the Robinsons were, even though the term did not exist back then, rock stars.

Montréalers’ support for their new hero manifested itself in many ways. On June 30, after Robinson was roughed up on the basepaths early in game one of a doubleheader by Rochester Red Wing Danny Murtaugh, the crowd turned on the future Pirates manager and did not let up the rest of the day.21 In August, Baltimore hurler Stanley West, who had thrown inside pitches to Robinson in three straight at-bats, was told by the crowd that he would have to answer for his conduct after the game if he kept this up. West considered the threat serious enough that he threw nothing but outside pitches in Robinson’s following plate appearances.22

The well-known actor from the Quebec scene Marcel Sabourin reminisced how every little boy in town wanted to be Jackie Robinson during the summer of ’46: “His pictures were in our scrapbooks. … Instantaneously, he became our idol.”23 There was such high demand for his autograph that he could never eat a hot meal when he was out on the town.24 And when he joined members of the Montréal Canadiens for a visit to the city’s veterans hospital, he stole the show from the Stanley Cup champions.25

Montréalers, Quebecers, Canadians had a role to play in the great experiment of integration, and their conduct was irreproachable. But they were never tested in any significant way. The Royals took first place in the International League in late May and never relinquished that lead. As for Robinson himself, he won the league’s batting crown with a .349 mark. He had a .468 on-base percentage and scored 113 runs, both tops in the International League.

Even more remarkably, he never went through any prolonged offensive drought. His lowest batting average for any month of the season was .319 in an injury-plagued month of June. His defensive play was stellar, and he kept Royals fans on the edge of their seats with his daring baserunning. Would the support have been as unwavering had the man Wendell Smith called “The Black knight of Pasadena” hit .249 for a last-place club? That’s a question that can never be answered. But one thing is certain: Local rooters treated Jackie Robinson wonderfully, and he never gave them any reason not to.

The love affair between the Robinsons and Montréal did not stop at the gates of Delorimier Stadium. The newlyweds settled in the Villeray neighborhood, in the northeastern part of town. Back then, Villeray was overwhelmingly White, French-speaking and Catholic. Yet, the Protestant, Black couple who had no knowledge of French felt welcome as soon as they settled into their apartment.

The neighbors took very good care of Rachel, who was pregnant with the couple’s first child, when the Royals were on the road. Kids helped her carry groceries, she was given extra rationing coupons, and when a few days went by without her being seen outside, someone would knock on the door to make sure she was all right.26

The fact that the Robinsons received regal treatment in Canada should not give anyone an exaggerated sense of nationalistic bravado. Although the contrast was stark with what was happening in the Southern United States, Canada was not an Eldorado for its Black population. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 1939 that drinking establishments were within their right not to serve Black customers, thus legalizing racial discrimination.27

And that joyous scene of Jackie Robinson being chased down the street “not because of hate, but because of love” happened a month before Viola Desmond was dragged out of a Nova Scotia theater and jailed for having watched a movie from the main floor while being Black.28

Jackie Robinson certainly enjoyed the love he received in his temporary home. But given everything he had to deal with, he would have benefited greatly from a little less love and a little more peace and quiet while in Montréal. There was the pressure of succeeding in Triple A. The pressure of making a living for himself, his wife, and their coming child. The rough treatment he received from opponents and fans in some cities. Also, he was never quite accepted by his teammates. A fan ran into Royals in a restaurant that summer and heard the White ballplayers lament that the team’s catalyst was taking a job away from a White player.29

Also resting on Robinson’s shoulders was the gigantic amount of pressure that came with being a standard-bearer for African Americans. “I think Jackie really felt,” said Rachel Robinson, “that there would be serious consequences if he didn’t succeed and that one of them would be that nobody would try again for a long time.”30

The newspapers of the Black community were also quick to remind Jackie, John Wright, and Roy Partlow, a Negro League pitcher who was signed in May to replace Wright on the Royals roster, that they were not playing only for themselves. Partlow was not happy when the club demoted him to Class-C Trois-Rivières (where he joined Wright). Wendell Smith had some harsh words for the veteran southpaw, calling him “an eccentric prima donna’ and a problem child of no small means” and reminded him of the “14 million Negroes from coast to coast who are pulling for him to make good in organized baseball.”31

The pressure, the stress and the hatred almost got the better of Robinson that season. By late August he was pretty much burned out, and a physician told him to take time away from the team and rest. Even though he wrote in his autobiography that he asked back into the lineup after one day for fear of being accused of protecting his lead in the league’s batting title race,32 box scores show us that he missed two games and benefited from a rainout, for a total of three days off. Robinson also told reporters in the spring of 1947 that manager Hopper had asked him to cut his vacation short as the team was slumping. There was no mention of the batting championship at that time.33

Those three late-season off days did little to improve Robinson’s health. It’s a wonder that a man in his condition found a way to excel — and keep his composure — on the field over the course of the three high-stakes, high-pressure, best-of-seven playoff series the team played that year. He was shown a black cat by members of the Syracuse Chiefs during an International League championship series game, but persevered.34 He was jeered like never before, and two Louisville Colonels tried to spike him when the Royals traveled to Kentucky to play in the Junior World Series.35 But he kept on going. When the series shifted to Montréal, local fans booed every single Colonels player, as retribution for the way Robinson had been treated in Louisville.

The Royals’ number 9 exacted revenge with his bat and his glove. He walked off the Colonels in Game Four, was instrumental in the Game Five triumph, and before the pandemonium that followed his farewell performance as a Royal, the spotlight shined on him one final time in Game Six. Veteran hurler Curt Davis played with fire for eight innings, but still managed to get to the top of the ninth without having surrendered a run. He quickly found himself in trouble again, with Colonels on first and third and nobody out. Louisville’s Al Brancato hit a hot shot to second that Robinson handled beautifully. He stepped on second and threw to first for a rally-killing double play.

Montréalers went wild, as they had done so many times during the season. After one final groundout, players and fans alike could let loose and celebrate. The social experiment of baseball’s integration hadn’t resulted in violence and disorder, as its opponents had forecast for decades. It had produced a winner.

Oddly enough, Robinson’s next game at Delorimier Stadium almost resulted in a riot. The Dodgers came to Montréal during the 1948 All-Star break to play the Royals. It had been decided beforehand that Robinson would go to the plate once and sit out the balance of the game to rest his ailing back. But that piece of information had not been disclosed, and the 17,000 fans who had bought tickets, in large part to see Jackie Robinson in action one more time, were livid. So much so that Branch Rickey had to do some damage control. Brooklyn forfeited its part of the gate to set up a new fund to help Montréal-area amateur baseball.36 The love affair between Robinson and the city was still going strong.

“When fans go to bat for you like that,” Robinson said in response to the support he got during game four of the Junior World Series, “you feel it would be easy to play for them forever.”37 In a city in which, more than three-quarters of a century later, you can find so many reminders of his short passage (including a statue and two murals), a lot of fans wish he had.

Historian MARCEL DUGAS is a graduate of the University of Montréal. He’s been researching the Montréal Royals since 2012. In 2013 he live-tweeted the team’s 1946 season for the benefit of his followers across Canada, the United States, Latin America and elsewhere. In 2019 he published Jackie Robinson, Un été à Montréal (Jackie Robinson’s Summer in Montréal), a deep dive into the historic 1946 season.

Notes

1 Phil Séguin, “Montréal Gagne la Petite Série,” La Patrie, October 5, 1946: 50.

2 Sam Maltin, “Lesson of Goodwill Among Men, Fans ‘Mob’ Jackie in Great Tribute to Star,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1946: 1, 12.

3 “Le Royal Crée un Précédent dans l’Histoire du Baseball Organisé,” La Presse, October 24, 1945: 18.

4 Dink Carroll, “Playing the Field,” Montréal Gazette, October 25, 1945: 16.

5 Dink Carroll, “Royals Set Precedent, Sign First Coloured Ball Player,” Montréal Gazette, October 24, 1945: 14.

6 “Le Royal Crée un Précédent dans l’Histoire du Baseball Organisé.”

7 “Joueur N Mis Sous Contrat par les Royaux,” Le Devoir, October 24, 1945: 11. The altered word in the title is the French equivalent of the N word.

8 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson and his Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 67.

9 “Cuban Giants vs Le National,” La Presse, July 13, 1896: 2.

10 Tygiel, 91.

11 “John Wright, un Autre Joueur N Est Mis Sous Contrat par les Royaux,” Le Canada, January 30, 1946: 7. See Note 7.

12 Roger Kahn, Rickey & Robinson, the True, Untold Story of Integration of Baseball (Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale, 2014), 200.

13 Kahn, 207.

14 “On Veut Avoir Robinson,” Le Droit, March 20, 1946: 13.

15 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995), 43.

16 Tygiel, 122.

17 Tygiel, 128-129.

18 Charles Mayer, “Avec le Royal et dans l’Internationale,” Le Petit Journal, May 5, 1946: 47.

19 Wendell Smith, “Jackie Gets Ovation in Home Debut,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 11, 1946: 12.

20 Camil Desroches, “Carrousel Sportif,” Le Canada, May 2, 1946:11.

21 Phil Séguin, “Battu Samedi, Montréal Divise Hier,” La Patrie, July 1, 1946: 12.

22 Sam Maltin, “Jackie Denies He Will Quit Baseball and Return to School,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 24, 1946: 17.

23 Marc Robitaille, Une Vue du Champ Gauche (Montréal: Les 400 coups, 2003), 174.

24 Sam Maltin, “Royals May Attract Million in 1946,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 20, 1946: 16.

25 Sam Maltin, “Jackie, Hockey Stars Visit War Veterans,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 29, 1946: 19.

26 Tygiel, 124.

27 Eric Adams, “The Fred Christie case (Christie v York),” Canadian Encyclopedia, April 5, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fred-christiecase, accessed July 6, 2021.

28 Russell Bingham and Eli Yarhi, “Viola Desmond,” Canadian Encyclopedia, January 27, 2013. https://www.the-canadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/viola-desmond, accessed July 6, 2021.

29 William Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montréal Royals (Montréal: Robert Davies Publishing, 1996), 109.

30 Tygiel, 139.

31 Wendell Smith, “What Happened to Roy Partlow?,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 20, 1946: 16.

32 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 49.

33 Wendell Smith, “Jackie Almost ‘Cracked’ Last Year,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 15, 1947: 16.

34 Sam Lacy, “Didn’t Mind It, Balto; Syracuse Worse,” October 1, 1946: 20.

35 Sam Lacy, “Robinson Victim of Rebel Boos in Series,” October 1, 1946: 20.

36 “Les Dodgers Remettent une Somme de $8,000 au Montréal,” La Presse, July 21, 1948: 20.

37 Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montréal Royals, 110.