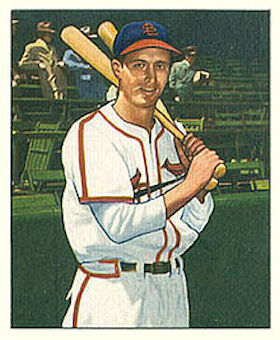

Harry Walker

Harry Walker was born to baseball and spent his life in the game. The son of one major leaguer and the brother of another, he was an All-Star outfielder, the lightning-rod manager of three teams, and a controversial hitting guru. Harry and Dixie Walker are the only brothers to win batting titles.

Harry Walker was born to baseball and spent his life in the game. The son of one major leaguer and the brother of another, he was an All-Star outfielder, the lightning-rod manager of three teams, and a controversial hitting guru. Harry and Dixie Walker are the only brothers to win batting titles.

When Harry came up with the St. Louis Cardinals, he was known as “Little Dixie.” His brother was eight years older; Harry always called him by his given name, Fred. Harry’s enduring nickname, “Harry The Hat,” came from his compulsive fiddling with his cap between pitches. An unnamed writer provided a play-by-play of his routine: “Cap off, cap on, tap left foot with bat, cap off again, tap right foot with bat, cap on again, adjust cap with left hand, cap off again, rub sleeve across face, cap on again, adjust cap with right hand, tap foot.”1 Walker said he wore out a dozen caps every season. Not to mention thousands of spectators.

Walker didn’t drink alcohol or coffee, but he always seemed wired. From childhood until he died at 80, he never stopped talking baseball. He made Casey Stengel look like a wallflower. “Some people might not have liked Harry Walker because he talked all the time,” said one of his bosses, Astros general manager Spec Richardson, in a considerable understatement; Walker drove many people crazy. “That didn’t bother me. If you’d listen to him, you’d learn a lot.”2

Harry William Walker was born on September 22, 1918, in Pascagoula, Mississippi, where his father was playing for a shipyard team during World War I.3 Ewart Gladstone Walker, the original Dixie, pitched for the Washington Senators from 1909 to 1912 and roomed with Walter Johnson. Ewart’s brother Ernie also played in the majors. Harry’s mother was the former Flossie Vaughn.

The Walkers moved back to their home in Alabama after the war, and Harry lived there for the rest of his life. He told his first-grade teacher he planned to be a ballplayer. “I just followed the family,” he said.4 When Harry was 14, Fred made the majors for his first full season with the Yankees. Harry visited his brother in New York and hung out with Fred’s teammates Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. “I dreamed about it for months afterwards,” he said.5

Harry’s professional career got off to a stuttering start. Like his brother, he played the outfield and batted left-handed and threw right. He went with Dixie to the Yankees’ spring camp in 1936, but the club showed no interest in a 17-year-old who weighed around 140 pounds. Signed by the Cleveland organization the next year, he suffered a burst appendix in his first season and a hernia that ended his second. When he hit .322 at Class B Pensacola in 1939, the Cardinals spotted him and signed him.

St. Louis started Walker at the top minor-league level in 1940. Playing center field for Columbus, Ohio, he hit .313 with 17 home runs. That earned him a September call-up for seven games. The next spring, while competing for a big-league job in St. Petersburg, Florida, he married his high school girlfriend, Dorothy Fulmer, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, then started that afternoon’s game. Dixie, who had become a star with the Dodgers, was best man at the wedding, and a few days later the brothers appeared together in a professional game for the first time when the Cardinals played Brooklyn in an exhibition game.

After another seven-game cameo with the Cardinals in 1941, Harry went back to Columbus. The Columbus Red Birds won the American Association pennant and met Montreal, the International League champion, in the Junior World Series. Columbus trailed 8–6 in Game Six when Walker delivered the storybook ending: bottom of the ninth, a two-out, two-strike home run that won the game and the series. His teammates carried him off the field. He called the homer his biggest thrill, even after another hit that won the major-league World Series in 1946.

Walker stuck with St. Louis in 1942, but another rookie, Stan Musial, beat him out for the left-field job. Walker served as a backup for one of the greatest outfields in history: Musial, Terry Moore in center, and Enos Slaughter in right. Playing in 74 games, Walker produced outstanding results: .314/.355/.398.

Moore was blocking his path to a regular job in center field. Rather than feeling threatened, the Cardinals captain became the younger man’s mentor. Moore instructed Walker not to talk to opposing players, not even his brother, but Harry didn’t mind; he said, “Terry would chew you out in a nice way.”6 When Harry and Dot’s first child was born, on January 5, 1943, they named him Terry Nolen Walker.

Moore and Slaughter went into the army after the 1942 season, and Walker took over center field as St. Louis won its second straight pennant in 1943. Although he was a big man at 6-foot-2 and 180 pounds, he was a slap hitter who totaled only 10 home runs in his career. He reeled off a 29-game hitting streak, the longest of the year in the National League, plus another 26-game streak. He hit .294/.341/.376 and was chosen to start the All-Star Game.

On the morning after the Yankees defeated St. Louis in the World Series, Walker and teammate Alpha Brazle reported to the US Army. They went to Fort Riley, Kansas, for basic training, where Walker caught spinal meningitis. He became so delirious that he was strapped into a straitjacket. Only the new “miracle” drugs, antibiotics, saved his life.

After he recovered, the Army shipped him to Europe with the 65th Infantry Division. The division landed in France in January 1945 and joined General George Patton’s Third Army as it pushed eastward across Germany. Walker was assigned to a reconnaissance unit. “Sometimes we’d be 30 or 40 miles back of the German lines just like the scouts in the Old West.”7

Both sides knew the war was almost over. The scouts ran into small groups of German troops, some wanting to fight and some eager to surrender to the Americans before the Russians caught them. As the 65th Division reached the German-Austrian border, Walker was slightly wounded by shrapnel, which doctors left in his back.

One rainy night his unit came upon three confused German soldiers, who asked where the Americans were. One of the Germans caught on and raised his rifle in Walker’s face. “When I dropped out the door of my jeep, I hit [shot] him and the other two with a .45 revolver.”8

Within days the scouts encountered a larger force of enemy soldiers who were not ready to give up. Walker sprayed them with a .50-caliber machine gun, killing or capturing more than two dozen. He was awarded the Bronze Star for valor and the Purple Heart. He was proud of his wartime service: “Whatever price it took, it had to be paid.”9

After Germany surrendered on May 8, the division commander ordered Walker to put together a baseball team to entertain the troops. Walker finagled a B-17 to ferry the players around occupied Europe, making him the only private first class with his own aircraft. He joined an all-star team that played in the European Theater championship game before 50,000 soldiers at the Nuremburg stadium, the scene of Hitler’s frenzied rallies.

Walker turned himself into a pull hitter in the Army because he learned that soldiers dig the long ball. He brought that batting style home with him in 1946 and nearly ruined his career. Musial moved to first base, and Terry Moore was a part-time player, hobbled by sore legs and a bad knee. Presented with opportunity, Walker failed to win a regular job. He was batting under .200 until July. Two years wearing combat boots left him with weak arches and aching feet, and the aftereffects of meningitis made his back stiff.

He left the club in August when his 3½-year-old son was hit by a car. The boy suffered severe head and leg injuries, but Walker was back in the lineup three days later. A family emergency could not be allowed to interfere with the pennant race.

The Cardinals were locked in a tight race with the Dodgers (again). When the two clubs met in midseason, Dixie chose family over team loyalty. He advised his brother to shorten his swing, move his feet closer together, and wait on the ball. Harry switched to a heavier bat and began punching hits to the opposite field. He boosted his average to .237 in 385 plate appearances.

The pennant race ended in a tie for the first time in history, St. Louis and Brooklyn each winning 96 games. The Cardinals took two straight in the best-of-three playoff to claim their fourth pennant in five years.

Walker started five of the seven World Series games against the Red Sox, platooning in left field with Erv Dusak. In the decisive Game Seven, he drove in the Cardinals’ first run with a lineout (a sacrifice fly under today’s rules), and singled and scored another run. The game was tied, 3–3, in the bottom of the eighth, setting up one of the most dramatic moments in Series history.

Slaughter led off with a single, but stayed at first while Boston’s Bob Klinger retired the next two batters. Slaughter was running on the pitch when Walker sliced a liner that dropped in left-center. Center fielder Leon Culberson, subbing for the injured Dominic DiMaggio, flipped a casual throw to the cutoff man, shortstop Johnny Pesky. With St. Louis fans roaring, Pesky couldn’t hear his teammates yelling “Home! Home!” He turned and hesitated for a fraction of a second before he realized that Slaughter had rounded third at full throttle. “I knew I couldn’t hit him with a .22,” Pesky said.10 His late throw to the plate was a formality. Slaughter’s “mad dash” lives on in baseball lore along with Pesky’s double-clutch, while Walker’s double is a footnote.11

Walker skipped the next day’s celebration in St. Louis and hurried home to Leeds, Alabama, to meet his new daughter, Carole, who was born during the Series. He used his $3,600 Series check to build a stone house where he lived for the rest of his life.

The 1947 season was less than three weeks old when St. Louis traded Walker and a pitcher to the Phillies for outfielder Ron Northey. A few days later a bombshell story broke that left a lasting stain on the reputations of the Walker brothers.

The Cardinals had started slowly, losing nine in a row before they went to Brooklyn on May 6 and took two out of three from the Dodgers. The morning after that series, the New York Herald Tribune reported that some Cardinals players had plotted to organize a league-wide strike in protest against Brooklyn’s rookie first baseman, Jackie Robinson.12 Although the story contained major errors and cited no sources — and all the Cardinals denied it — the alleged strike threat has become part of history.

Without naming names, writer Stanley Woodward implied that the conspiracy had originated with Dixie Walker and been pushed forward by white southern players on the Cardinals. Of course, Dixie’s brother was a likely suspect. The Walkers, along with other southerners including Terry Moore, Marty Marion, and Enos Slaughter, have been branded as symbols of racist resistance to integration. However, in seven decades no hard evidence has surfaced to indicate that the strike talk was anything more than talk.13

Asked about it years later, Harry Walker lapsed into Stengelese: “Nothing was ever concrete on it. There was a rumor spread through the whole thing. And everybody was involved to a point, but that was never done.”14

The strike story makes the timing of the Walker trade look suspicious, but St. Louis had been trying for months to acquire Ron Northey, because manager Eddie Dyer wanted more power in his outfield. Walker left the defending World Series champion for the league’s never-ran, but later said the trade was the best thing that could have happened to him. His son, Terry, didn’t want to give up his Cardinals cap because “only my daddy was traded to Philadelphia.”15

As soon as he changed uniforms, Walker appeared to be a changed man. In less than three weeks he raised his batting average above .400. He and Dixie started the All-Star Game, batting first and second and playing side-by-side in the outfield for the only time in their professional careers.

Harry’s hot hitting continued. “There were times [in 1947] when I actually saw the ball strike my bat,” he said. “That’s how closely I followed it. This also enabled me to swing later and judge the pitch better.”16 He was skilled at working the count and waiting until he got a good pitch to hit. Using the closed stance his brother had recommended and choking up on a hefty 37-ounce, two-toned Johnny Mize-model bat, he led the league with a .363 batting average, .436 on-base percentage, and 16 triples. Dixie had led the National League in hitting in 1944.

Philadelphia fans voted Walker the city’s most valuable athlete, and a local restaurant gave him a new car. The goodwill vanished when he held out during the winter for a raise to $25,000. He signed for a reported $22,500, but the contract dispute landed him in manager Ben Chapman’s doghouse. Walker lost the center field job in 1948 to 21-year-old Richie Ashburn, a similar left-handed slap hitter who was much faster. Going from batting champ to pinch-hitter, Walker hit .292/.358/.355.

The Walkers’ son had never completely recovered from the 1946 car accident. In January 1949 Dot took Terry to Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia for hip surgery. The six-year-old’s heart stopped on the operating table, causing fatal brain damage. He died on February 2. Harry and Dot eventually had three daughters, but Terry was their first child and only son.

The Phillies traded Walker to the Cubs after the 1948 season, and Chicago passed him on to Cincinnati in June 1949, continuing his tour of the bottom of the league standings. He hit .318/.385/.389 for the Reds, but they sent him back to the Cardinals in December 1949 for an infielder and – wait for it – Ron Northey.

Eddie Dyer was still managing St. Louis in 1950, and had no use for Walker. Sentenced to a seat on the bench, Walker was batting .207 in August when Dyer sent him down to Triple-A Columbus. At 31, his major-league career was effectively over. “Dyer did me a favor and didn’t know it,” Walker said later.17

In 1951 Walker began a managing and coaching career that would keep him in professional ball for nearly three more decades. As player-manager of the Cardinals’ Triple-A Columbus farm club, he led the American Association with a .393 batting average. Although the Red Birds finished last, Walker impressed the Cardinals’ front office by teaching and nurturing a young, overmatched team. He won a promotion to the club’s premier Triple-A affiliate at Rochester and led that International League team to consecutive victories in the Junior World Series against the American Association champions in 1952 and 1953.

When St. Louis owner August Busch Jr. decided to replace manager Eddie Stanky in May 1955, Cardinals front-office executives recommended Walker over the team’s other Triple-A manager, Johnny Keane. The executives portrayed Walker as a good cop to wash away the memory of the belligerent, unpopular Stanky.

Taking over on May 28, Walker inherited a promising young club. The lineup, anchored by veteran stars Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst, included Wally Moon, the 1954 Rookie of the Year; Bill Virdon, who would win the award in 1955; and two budding power threats in Ken Boyer and Rip Repulski. But the pitching was atrocious, and the Cardinals finished seventh with a 68-86 record. Walker didn’t get a chance to do better. Busch hired a new general manager, Frank Lane, who brought in Fred Hutchinson as manager.

Walker went back to the farm system to manage Double-A Houston for the next three years and add to his resume. He led the Buffs to consecutive Dixie Series championships – Texas League versus Southern Association – in 1956 and 1957. He rejoined the Cardinals in 1959 as a coach under another new manager, Solly Hemus.

Walker had earned a reputation as a master teacher of hitting. He taped interviews with stars, including Ted Williams, and compiled them into a manual called “How to Hit.” But his methods were controversial. Critics complained that he wanted all hitters to be like him, punching singles to the opposite field. He insisted that only a few sluggers should try to uppercut and pull the ball. Those who profited from his instruction swore by him. After he helped Bill White, the Cardinals’ slumping first baseman, White said, “As far as I was concerned, Harry Walker had saved my major league career.”18

Hemus, a raucous imitation Stanky, was no more successful than his role model. When he was fired in 1961, Johnny Keane got the job. Walker again returned to the Cardinals’ farm system to collect more trophies. He was named International League Manager of the Year after his 1963 Atlanta club tied for first place in the league’s Southern Division. The next season he led Jacksonville to the IL pennant and won The Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year award.

Ten years after Walker’s brief taste of managing in the majors, he got a second chance. When Danny Murtaugh resigned as Pittsburgh manager after the 1964 season, Walker campaigned for the job. He didn’t know the Pirates general manager, Joe L. Brown, so he enlisted Branch Rickey, former Cardinals GM Bing Devine, and former manager Johnny Keane to call Brown and put in a good word. Brown’s interview with Walker went on for several hours, about average for a Walker conversation.

Having talked his way into the job, Walker proceeded to talk his way out. After the quiet Murtaugh, the motormouth new manager was a shock to the Pirates. The roster included three future Hall of Famers – Bill Mazeroski, Willie Stargell, and the incandescent Roberto Clemente – but Pittsburgh had finished sixth in 1964. Mazeroski missed the first three weeks of 1965 with a broken foot, and Clemente was weak from a winter bout of malaria. When the club opened the season 9-24, Walker erupted and ripped the players for a defeatist attitude.

He benched Clemente for a rest, and the prickly superstar threw a tantrum of his own, demanding to be traded. At a peacemaking breakfast, Clemente and Walker found common ground over their love of hitting. Clemente was a sensitive man who felt he was disrespected because of his Puerto Rican heritage; Walker recognized that he needed special handling. He took every opportunity to praise Clemente, calling him the best player in baseball, and they became friends.

But Walker’s coddling of the star alienated some of the Pirates. They thought the manager was too quick to bark at everyone else, even humiliating them in front of their teammates. Walker levied automatic fines for bonehead plays, then rescinded them after an angry clubhouse meeting. An anonymous player groused, “If he’d let us alone, we’d play ball.”19

The club got hot, and players and manager reached an uneasy truce. Winning can turn frowns into smiles. Following their sorry start, the Pirates played better than .600 ball the rest of the way and climbed to third place with 90 victories.

After the season center fielder Bill Virdon retired at 34, reportedly to get away from Walker. Another unhappy Buc, pitcher Bob Friend, was traded after 15 years with the team. To replace Virdon, Joe Brown acquired Matty Alou from San Francisco.

Alou turned into Walker’s prize pupil. A 160-pound left-handed hitter, the 27-year-old Dominican came to Pittsburgh with a .260 lifetime batting average. Walker gave him a heavier bat and urged him to slap the ball to left field and use his speed to beat out bunts — in short, to hit just like Harry Walker. Alou spoke poor English, so Clemente reinforced the message in Spanish. Alou led the league in 1966 with a .342 average and hit over .330 for the next three years. He said Walker’s influence made “all the difference possible.”20

While advising Alou to cut down his swing, Walker told Clemente the team needed him to hit for more power. Clemente responded with a career-high 29 home runs and 119 RBIs. He won his only Most Valuable Player award in 1966.

Pittsburgh held on to first place as late as September 10, and the manager appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated. The writer Jack Mann painted a compelling portrait: “Harry Walker is a big, homely sheep dog of a man, pawing desperately in his dedicated effort to be helpful on the field and friendly off it, and often making himself a pain in the neck in his overdone attempts at both.”21

The Pirates hung in the race until the final week. Their .279 batting average led both leagues, but the pitching was thin. The club won 92 games to finish third again, just three behind first-place Los Angeles. After the Dodgers’ ace, Sandy Koufax, retired, Las Vegas oddsmakers made Pittsburgh the pennant favorite for 1967.

While the players were still split between those who respected the manager and those who wanted to strangle him, Walker had handled a diverse roster without any reports of racial or ethnic strife. The veteran white star Mazeroski and the young black star Stargell couldn’t stand him. His biggest boosters were two Latinos, Clemente and Alou. On June 17, 1967, he started the majors’ first all-minority lineup, except for the pitcher.

The Pirates didn’t live up to their advance billing, and reporters said the clubhouse mood was ugly. “When you’re winning they say you have aggressive players when they spout off,” Walker said later. “When you’re losing, they call it dissension.”22

With the team in sixth place on June 30, GM Brown called a meeting and told the players to look at themselves instead of griping about the manager. Seventeen days later Brown fired Walker. Pittsburgh Press columnist Les Biederman wrote, “With Walker there always seemed to be a crisis.”23 The Pirates stood at 42-42 and stayed at .500 under the recycled manager, Danny Murtaugh.

Walker had no time for a vacation. Five days after he was canned, he had a new job as a hitting coach for the Houston Astros’ major and minor league teams. Astros manager Grady Hatton had been his teammate in Cincinnati. Walker didn’t need the paycheck; he owned a hardware store, a concrete-block company, and other businesses in his hometown. But he did need baseball.

Eleven months later Walker succeeded Hatton as manager. The Astros were in last place and had lost six straight when he took over on June 18, 1968. “This is still a young club here,” he said. “This is a profession like learning to be a doctor or lawyer.”24 He urged the fans to be patient.

The club was rich in young talent — Joe Morgan (out for the year with a knee injury), Jimmy Wynn, Rusty Staub, Larry Dierker — but fans and the front office were beginning to wonder if the kids were overrated; they were still losing, after all. Walker couldn’t lift the Astros out of the cellar. They finished behind their expansion brethren, the Mets, for the first time. During the winter the club traded its best hitter, the 24-year-old Staub, in the first of a series of deals that sent most of the Astros’ young core on to stardom in other uniforms.

Walker’s troubles in Houston began with spring training in 1969, when he laid down his rules and the fines for breaking them. The unmarried players were locked in a dorm at midnight. Each man had to run a mile in six minutes every day. It is not clear how much of this was Walker’s idea and how much was dictated by the meddlesome front office. The owner, Judge Roy Hofheinz, was never a patient man and was tired of waiting for a winner.

Walker absorbed the brunt of the players’ resentment, and that set the tone for his tenure. Making matters worse, the Astros stumbled to a 4-20 start in 1969. Just as quickly, they about-faced and took off on a 32-16 run to catapult themselves into a close race for the Western Division lead. (It was the first year of division play.)

But once again, Walker seemed to face a crisis a week as players bridled at his strict discipline, loud criticism, and nonstop talking. Caught out of his own time in the turbulent 1960s, he confronted a generation of players who were less willing to heed the wisdom of their elders, the lessons he had learned from his brother and Terry Moore. When the veteran pitcher Jim Bouton was traded to Houston in August, he found that many of his new teammates thought the manager was a colossal pain and a buffoon. Bouton disagreed: “Harry drives and harasses, reminds everyone how to run the bases, how to hit the ball, to watch for this, watch for that, and keeps everybody agitated and playing better baseball.”25

On September 10 the Astros stood just 2 games out of first place in the division. Then they swooned, dropping six in a row, to finish fifth at 81-81. But it was the first time the franchise had reached .500 in its eight-year history.

Walker’s reward: a one-year contract, hardly a vote of confidence. When the Astros started slowly in 1970, press reports said the manager was on his way out. GM Spec Richardson responded, “The papers are firing him, but I’m not.”26 A strong finish moved the club up to fourth place in the six-team division at 79-83 and earned Walker another one-year extension.

The Astros put up an identical record in 1971. Walker’s critics were unanimous: His time was up. Houston writer John Wilson said, “He has never been able to gain a rapport with the players, he over-manages during a game and he always shifts the blame away from himself when things go wrong.”27 During the final home stand, hand-lettered signs around the Astrodome proclaimed, “Goodbye Harry.” One man disagreed, and he owned the team. Judge Hofheinz gave Walker another year.

Far more damaging than any newspaper sniping was Walker’s toxic relationship with some of the Astros’ black players. He and outfielder Jimmy Wynn engaged in several shouting matches. Pitcher Don Wilson had to be restrained from attacking the manager. The harshest verdict came from second baseman Joe Morgan. More than 20 years later Morgan wrote that Walker “was, without question, the most blatant racist I ever met in baseball.”28 Why, Morgan said, Walker wouldn’t even wear black shoes. “There were any number of times he called team meetings when we weren’t going well and singled out only the black players on the team for criticism.”29

Walker thought the 5-foot-7 Morgan had “a little man’s complex” and a permanent chip on his shoulder. “He’s just hard to work with.”30 The sad fact is that Morgan was Walker’s kind of player: smart, fast, aggressive on the bases, and patient at bat. After the 1971 season the Astros traded him to Cincinnati, where he turned into one of the greatest all-around players in history.

Walker was the first Houston manager to last three full seasons. In the spring of 1972 he said, “When I managed at Pittsburgh, and when I first came to Houston, I tried to get 25 men to adjust to me. Now I’m adjusting to them.”31 And he did hold his tongue as the Astros climbed into first place in the division in May, then stayed close behind Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine for three months.

It was a different Houston team. Hofheinz had moved in the Astrodome’s outfield fences, igniting a power surge. The club had routinely been last in the league in home runs, but in 1972 the long ball output nearly doubled. The Astros were on their way to the best season in their history. They were still in second place, but had dropped 9 games back on August 26.

Walker was fired that day. His replacement: 67-year-old Leo Durocher, who had resigned from the Cubs at the All-Star break. GM Richardson hoped Durocher could conjure a late-season miracle, as he had with the 1951 Giants. No miracle this time. The Astros, 67-54 under Walker, went 16-15 for Durocher and finished third.

After nine full and partial seasons and 1,235 games as a major league manager, Walker’s record stood 26 games over .500. Few employees love their bosses all the time, but Walker had had too many public scraps with too many players. At 53, he had turned into a tiresome curmudgeon who railed against working mothers, welfare Cadillacs, and people too lazy to get a job. He criticized players for slapping palms instead of shaking hands after home runs. He never managed in pro ball again.

Walker wasn’t through with the game, though. He rejoined the Cardinals organization as a hitting instructor and scout. In 1978 the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), 30 miles from his home, hired him to create a varsity baseball program. UAB was only nine years old; its first basketball team began play that year, and it didn’t field a football team until 1991.32

Starting from scratch, Walker’s team won the Sun Belt Conference North title in its third year of existence in 1981 and repeated in 1982. The UAB Blazers played at Birmingham’s historic Rickwood Field until the university dedicated its own ballpark, the house The Hat built, in 1985. Walker posted a record of 211-171 during eight seasons before he retired in 1986. His number 32 was the first UAB baseball jersey to be retired.

He stayed close to the university as an adviser and host of an annual fundraising golf tournament. His three daughters and grandchildren lived nearby. In 1999 Dot Walker began chemotherapy treatment for lung cancer. One morning in July she couldn’t wake her husband. The 80-year-old Walker had suffered a stroke during the night and died three weeks later, on August 8, 1999.

“I lived such a good life because of baseball, it is hard for me to go back and say what else I could have done,” he told a writer late in his life. “The only thing I never had that I really wanted was a jet airplane. I can’t afford that now, but if I could I’d have one. I’ve had all of the other good things. I’ve been all over the world. I’ve had the best of lives.”33

Notes

1 “Erskine Excites Rickey,” New York World-Telegram, June 23, 1949, in Walker’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York. A Philadelphia writer, Stan Baumgartner, is generally credited with coining the nickname in 1947.

2 Larry Powell, Bottom of the Ninth: An Oral History on the Life of Harry “The Hat” Walker (Lincoln, Nebraska: Writer’s Showcase, 2000), 202.

3 Baseball encyclopedias give Walker’s birth date as October 22, 1916. That is wrong. Newspaper stories during his playing and managing career give his correct age. The mistake appears to have been introduced into the records in the 1970s. Walker said he was born in 1918, and census and military records agree. September 22, 1918, is the birth date on his gravestone. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=6929399&PIpi=2241210, accessed February 26, 2016. Larry Powell, who recorded extensive interviews with Walker for the book cited above, confirmed that the gravestone is correct. Telephone interview by the author, April 15, 2016.

4 Cynthia J. Wilber, For the Love of the Game (New York: William Morrow, 1992), 333.

5 Hub Miller, “Harry, the Hat,” Baseball Magazine, undated 1948 clipping: 265. In Walker’s HOF file.

6 George Vecsey, Stan Musial: An American Life (New York: ESPN, 2011), 129.

7 Powell, 74.

8 Wilber, 339.

9 Powell, 77.

10 “Pesky Blames His Lapse for Final Run in Series,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), October 23, 1946: 4.

11 Walker, like many others, believed the hit should have been scored a single and he took second on the throw to the plate. He said he never would have taken a chance of making the third out while Slaughter was heading home. Bob Broeg, “Former Cardinal Harry Walker talked and played a good game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 10, 1999, in HOF file.

12 Stanley Woodward, New York Herald Tribune, May 9, 1947, reprinted in TSN, May 21, 1947: 4.

13 For accounts of the alleged strike threat, see Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment (New York: Vintage, 1984); and Jonathan Eig, Opening Day (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007).

14 Vecsey, 235.

15 Russ Davis, “They Call Him The Hat,” Sportfolio, April 1948: 16.

16 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, March 16, 1948: 38.

17 Powell, 118.

18 Bill White with Gordon Dillow, Uppity (New York: Grand Central, 2011), 64. White, a black man who served as president of the National League, became a friend and fishing buddy of Walker’s.

19 Les Biederman, “Automatic Fines Eliminated as Walker Makes Peace With Bucs,” TSN, July 31, 1965: 20.

20 Biederman, “Bucs’ Matty Lifts Mark 100 Points,” TSN, September 26, 1966: 3.

21 Jack Mann, “The Voice of the Pirates,” Sports Illustrated, September 5, 1966. http://www.si.com/vault/1966/09/05/608894/the-voice-of-the-pirates, accessed March 10, 2016.

22 John Wilson, “The Hat’s Credo — Plenty of Patience,” TSN, July 6, 1968: 20.

23 Biederman, “Walker Liked All Players – Some Better,” Pittsburgh Press, July 20, 1967: 32.

24 Wilson, “The Hat’s Credo.”

26 “Astros Won’t Doff The Hat,” United Press International, June 19, 1970, in HOF file.

27 Wilson, “Durocher’s Far East Junket Detours to Houston,” TSN, September 9, 1972: 9.

28 Joe Morgan with Richard Lally, Long Balls, No Strikes (New York: Crown, 1999), 266.

29 Morgan and David Falkner, Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball (New York: W.W. Norton, 1993), 112.

30 Jimmy Cannon, “Astros Could Explode If Harry Doesn’t,” syndicated column in the Boston Record, March 23, 1972, in HOF file.

31 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, undated (1972) column in HOF file.

32 Until 1969 the Birmingham campus was a satellite of the state’s flagship university in Tuscaloosa.

33 Wilber, 337.

Full Name

Harry William Walker

Born

September 22, 1918 at Pascagoula, MS (USA)

Died

August 8, 1999 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.