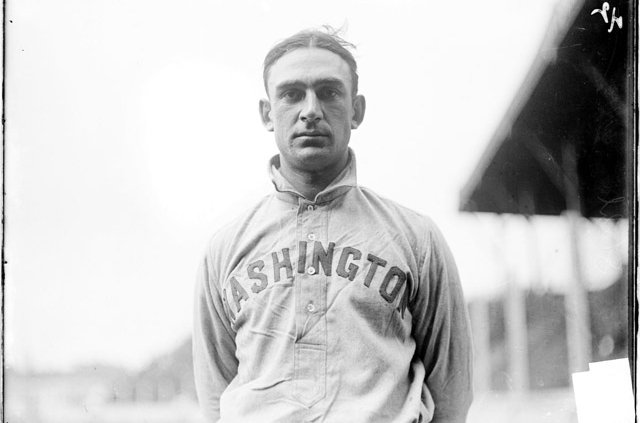

Boileryard Clarke

Boileryard Clarke was known throughout the major leagues for his booming voice that could be heard clearly all over the field. It served him well as both a catcher – a coach on the field – and as a college coach from the dugout. Clarke spent 55 years in baseball as both a professional player and collegiate coach, but during his later years was unclear about exactly when he took an interest in the game. “I can’t recall where I picked up baseball,” he told an interviewer, “I used to hook school to go watch the boys play baseball. Every time I hooked I used to get a licking which was pretty frequent.”1

Boileryard Clarke was known throughout the major leagues for his booming voice that could be heard clearly all over the field. It served him well as both a catcher – a coach on the field – and as a college coach from the dugout. Clarke spent 55 years in baseball as both a professional player and collegiate coach, but during his later years was unclear about exactly when he took an interest in the game. “I can’t recall where I picked up baseball,” he told an interviewer, “I used to hook school to go watch the boys play baseball. Every time I hooked I used to get a licking which was pretty frequent.”1

William Jones Clarke was born to John and Mary Clarke on October 18, 1868, in New York City. His father moved the family of 10 to St. Louis by 1880 and to Santa Fe by 1885 to help build an Indian school.2 Census records listed Clarke’s father as either a mason or a carpenter.

Clarke entered Brothers College in Santa Fe (now Santa Fe University of Art and Design), a Catholic school, sometime between 1886 and 1889. “I used to play ball with the priests there. … They told me I had a natural gift for the game,” he recalled many years later. “It’s a funny thing, though – there was never any thought in my mind that I would ever play for pay. I just wanted to play.”3 He joined the Aspen and Pueblo baseball teams of the Colorado State League in 1889. According to an interviewer, Clarke’s “most prominent blurb used throughout interviews [was] ‘it’s not a matter of where you’re going to play but how much you get to play. If you were getting $25 a month then, you were getting real money.”4 This can explain the road by which many Deadball Era players like Clarke took to the major leagues. After a season in Colorado, Clarke played for the Ottumwa club of the Illinois–Iowa League in 1890, went west and played for the San Francisco Metropolitans in 1891 and the San Jose Dukes in 1892. “I caught every day,” he said.5 It was in California that Clarke’s door to the major leagues opened.

A San Francisco acquaintance suggested that Clarke look into playing for the Baltimore Orioles of the National League in 1893. He had telegram offers from Louisville, Chicago, and Philadelphia as well but decided to sign with the Orioles. Clarke said, “It was a very fortunate move on my part because the Orioles (then in eighth place in a 12–team league) turned out to be a championship ballclub.”6 Clarke said he didn’t care whether or not he played in Baltimore or California because any team would have signed him. “As I walked into the hotel when I arrived in Baltimore I remember seeing Mike Kelly, Bill Brown, and Ed Gunther sitting in the lobby.” He said, “I thought my chances were practically nil” and told Heinie Reitz, “It doesn’t look like we’ll have much opportunity with all these big leaguers here.”7 Major–league clubs scoured America trying to find any talent that would help them win the pennant. Signing players from obscure minor leagues was typically cheap and worth a tryout during spring training or the season.

By February 1893, Baltimore’s acquisition of Clarke was made public in the Baltimore Sun. “Clarke is a catcher of great promise,” the Sun wrote. “He played 84 games last season in the California League. He ranked second in fielding, went to the bat 335 times, made 93 base hits, 24 sacrifice hits, 48 runs, stole 27 bases, and had a batting average of .277.”8 The 1892 Orioles finished in eighth place but manager Ned Hanlon began to make wholesale changes to the roster for the 1893 and 1894 seasons. He traded veteran Tim O’Rourke for Harry Taylor and a young shortstop named Hughie Jennings. Harry Stovey was released. Dan Brouthers and Willie Keeler were acquired. Only four players who were on the 1892 Orioles were still on the team in 1894: catcher Wilbert Robinson, infielder John McGraw, outfielder Joe Kelly, and pitcher Sadie McMahon. The Orioles went from consecutive eighth–place finishes in 1892 and 1893 to champions of the National League in 1894. From 1894 to 1898, the Orioles finished first in the National League three times and second twice, and won the Temple Cup twice.

While Clarke was in Baltimore he met and married Isabelle Taylor Thomas. Census records show that the couple were listed as living in Baltimore through at least 1920 despite Clarke’s playing in Boston and coaching Princeton University’s baseball team. While a member of the Beaneaters, Clarke opened a café and bowling alley with his brother, Stanton, on Fayette Street in Baltimore.9 The Clarkes had two sons: Oscar Taylor Clarke, born March 21, 1899, and William Jones Clarke II, born in 1902, died in 1905. In 1922 the couple moved to Princeton full time and remained there until Clarke died in 1959.10

In 1897 Clarke and Robinson split catching duties but both missed about two weeks with injuries. Clarke, while idle, helped to coach the Princeton baseball team for their game with Yale. Evidently his tutelage helped as the Tigers defeated Yale 22–7. Sporting Life wrote in 1898 that Clarke considered coaching the Tigers in the spring, which the paper said “would benefit him as well as them, as he could get into fine throwing and batting trim by practice in the Princeton cage.”11

Clarke served primarily as a backup to Wilbert Robinson in his six seasons with the Orioles (1893–1898) and slashed .259/.321/.330 with 349 hits, 50 doubles, 5 home runs, and 214 RBIs. He and Robinson virtually split catching duties in 1898. In 1899 Clarke signed with the Beaneaters. “The news that Boston had secured Baltimore’s tried and true backstop was a decided surprise to the base ball world,” commented Sporting Life.12 Clarke was considered a coach on the field at the time. Manager Frank Selee said, “Clarke will give us a taste of his old time Baltimore coaching, of course, and it will doubtless prove as popular to the local cranks as it was unpopular when he was with Baltimore.”13

Clarke proved to be popular with the Boston fans in his two seasons with the Beaneaters. He was a capable backstop who handled the pitchers well, called a good game, and played hard. “His throwing has been magnificent,” wrote Sporting Life. “Clarke keeps the men going in good style, steadies his pitcher and never gives up when there is a chance in sight.”14 He suffered a broken hand late in the 1899 season against Chicago but hadn’t realized the injury until he returned to Boston after the road trip. Sporting Life commented, “Bill was sadly missed by the patrons (in Boston). He certainly could not be charged with any lack of ginger.”15

Clarke’s first season in Boston was subpar even by backup–catcher standards. He played in 60 of the team’s 152 games in 1899 and slashed .224/.270/.283 with only two home runs and 32 RBIs. Clarke had his best major–league season at age 31 when he slashed .315/.344/.359 with one home run and 30 RBIs. (His batting average was 59 points higher than his career average.) Sporting Life exclaimed in late June, “Catcher Bill Clarke has struck his gait and is putting up the finest kind of ball imaginable. … Boston made a better investment than was at first imagined when it secured this man. Bill has put to blush the critics that hinted he was not the real thing. He is strawberries and cream with a vengeance.”16

On June 11, 1900, at the Sturtevant House in New York City, a new baseball union was formed, the Protective Association of Professional Base Ball Players, or Players’ Protective Association. Clarke was one of the three Boston delegates to the meeting, indicating the degree of respect other players had for him.17 The purpose of the union was to “counteract the despotic policies and grasping methods of the little coterie of ancient fossils who are gradually running the League and even the national game to death,” Sporting Life said. “The players have at last learned that the only way to meet the League trust is with counter organization.”18

At the meeting the players were addressed by Daniel Harris of the American Federation of Labor. Harris told them that their grievances, if handled properly, could be rectified without much trouble from the League. He said the union did not have to affiliate with the AFL immediately, or at all, but would receive the support of the AFL regardless. The delegates elected not to affiliate with the AFL at that time because they did not want to antagonize the League. This softer approach differed from that taken by the previous players’ brotherhood and Players’ League of 1885–1890. Officers were elected but not made public and a committee on bylaws was established. Each club chose one delegate to act as a representative of their club.

The Association reconvened on July 30 at the Sturtevant House. Clarke was elected treasurer.19 In December Clarke told Sporting Life, “I hope … every player will stick and refuse to sign until the League gives us a proper recognition. The men have all pledged themselves to stand together, and I believe they will. We would look ridiculous indeed if we gave in at the very first clash. The magnates may think we are bluffing, but they will find out their mistake.” He said that the organization was healthy financially because of its $5 initiation fee and $2–a–month dues during the season.20

In 1890 three major leagues totaling 24 teams competed against one another in a terrific baseball war. But the Players’ League collapsed after the 1890 season and the American Association folded the following year, leaving the National League with a major–league monopoly. Baseball suffered. After the 1899 season the National League dropped the least profitable teams, Baltimore, Louisville, Cleveland, and Washington. In 1901 when organizer Harry D. Quinn seemed to have the league prepared to actually play ball that year.

Clarke was listed as a catcher on the Boston reserve list after the 1900 season but in early 1901 Sporting Life reported that he became part–owner and manager of the Baltimore Association club. “Clarke professes to be in the brightest hopes, says he will get his release from Boston for nothing,” the paper said.21 He told Sporting Life that a Baltimore resident had the necessary capital to establish a club in Baltimore but that he could not sign players because the Players’ Protective Association forbade players to sign contracts at that time.22 Unfortunately for Clarke and others involved, the league dissolved before ever taking the field, thanks in part to the newly organized American League. Clarke’s career as a big–league owner and manager lasted a few weeks.

Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe reported in Sporting Life that the Beaneaters had planned to release Clarke before the 1901 season. He jumped to the upstart American League instead. Beaneaters director J.B. Billings made light of the move, saying, “I was wondering what we would do with him if we kept him.”23 Clarke played with Washington for four years, batting .251 over the period as a platoon catcher. Washington released him in 1905 and he signed with the New York Giants, joining former Baltimore teammate John McGraw. Clarke slashed .180/.241/.240 in 31 games. The 1905 season was Clarke’s last in the major leagues; his contract was sold to Toledo of the minor–league American Association. He played for Toledo in 1906 and1907, Minneapolis in 1908, and Albany in 1909 before retiring as a player. He acted as player–manager for Albany in 1909 and manager in 1910 but abruptly tendered his resignation to club president Charles M. Winchester in April 1911. Winchester said of Clarke, “His resignation came to me as a big surprise. … I always considered Bill Clarke to be one of the most competent and capable managers in the country. His judgment of baseball players was excellent and he was always given a free rein to build up a team. … Clarke in my estimation was a conscientious, honest ballplayer. He knew every department of the game and added prestige to the team.”24 Sporting Life wrote that Clarke was well liked and “his sterling qualities of manhood placed him high in the estimation of the fans. … His famous ‘W–e–o–o–w’ while on the coaching line at first base will live long in the hearts of fans in this city.”25 Hence the nicknames Roaring Bill and Boileryard.

Throughout his career, Clarke was lauded for his baseball intelligence and ability to be a manager on the field. Since his time in Baltimore, Clarke helped train and coach the Princeton baseball team before going to spring training. He is listed as the manager in Princeton’s records beginning in 1900 and served in that capacity in three stints: 1900–1917, 1919–1927, and 1936–1944.26 In 1910 Clarke became Princeton’s first paid coach.27 Sporting Life noted in its April 29, 1911, issue that Princeton was anxious to sign him to a three–year contract worth $9,000. Clarke also worked as a scout for the Detroit Tigers in 1911 in addition to his duties as Princeton coach.28 Clarke managed a group of YMCA baseball players in Europe in 1918 during World War I which would explain why 1918 was the only year between 1900 and 1927 that he did not coach the Princeton team.29

In 1915 Clarke co–wrote Baseball: Individual Play and Team Play in Detail with Fredrick T. Dawson.30 The book’s focus was baseball theory from the perspective of coaches and players. The authors wrote: “Although it is a sport which is widely followed, yet comparatively few players, and fewer spectators really understand it thoroughly. … In the present work, the authors, after careful study based on personal experience, injury, and comparison, have formulated for the general public, including the amateur and professional player, the whole subject of baseball as it is played in the most advanced circles, namely, in the major leagues.”31

Clarke and his wife moved to Princeton in 1922 and lived in the basement of their antique shop at 76 Nassau Street.32 He retired as coach in 1927, but was rehired in 1936. He retired for good in 1944. Overall, Clarke’s record at Princeton was 564–322–10 and only six of his teams failed to post winning records. He led the Tigers to Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League championships in 1941 and 1942. On May 17, 1939, the Tigers played Columbia at Columbia’s Baker Field in the first televised baseball game, won by Princeton 2–1. Clarke coached two future major leaguers, Moe Berg and Charlie Caldwell. During his last coaching stint with Princeton, in 1939, the university created the William J. Clarke Award, presented annually to the Princeton team’s best player.33 Princeton’s baseball diamond, Clarke Field, is named after him.

The university honored Clarke with gala parties, for his 80th and 90th birthdays. Friends, alumni, former players, and former opponents joined in the festivities. Clinton W. Blume, a former player for the Colgate baseball team, told Clarke in a letter on his 90th birthday, “Besides having the admiration and respect of the men that played for you, you also had the respect and admiration of the opposing players.”34 In an article by Asa Bushnell in the October 1958 Princeton Alumni Weekly, Clarke reminisced on his 90 years and his time at Princeton. “Ninety years old today, still–spry Bill Clarke honestly believes his first baseball–induced fractured thumb was his ‘luckiest break,’” Bushnell wrote. “That injury, suffered in the spring of 1897, brought him to Old Nassau.”35 Clarke remembered, “We’d been on a road trip. … When we got back to Baltimore, the manager said I couldn’t do anything to help our club for a while because of my thumb. He said Princeton University needed someone to straighten out its team – they were having a terrible time with the infield. I didn’t even know where Princeton was … but I agreed to give it a try.”36

Princeton alumnus George H. Sibley in a letter to Clarke on his retirement, said, “I don’t suppose that a man who has endeared himself as you have to the hearts of so many young men, an affection which abides with them always, realizes fully the lasting contribution you have made to the development of their characters.”37

Notes

1 Super Sports Feature on Bill Clarke, William J. Clarke, Faculty and Professional Staff files, Box 101, Princeton University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

2 Ancestry.com and Super Sports Feature on Bill Clarke, William J. Clarke, Faculty and Professional Staff files, Box 101, Princeton University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

3 Asa Bushnell, “Bill Clarke’s 90th Birthday,” Princeton Alumni Weekly, Vol. 59, No. 7, October 31, 1958: 5.

4 Super Sports Feature on Bill Clarke.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 “Sporting News: Baltimore Base–Ball Players,” Baltimore Sun, February 4, 1893: 6.

9 “Baltimore Bulletin,” Sporting Life, July 15, 1899: 10.

10 Super Sports Feature on Bill Clarke.

11 “Oriole Perquisites,” Sporting Life, January 15, 1898: 3.

12 “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, March 11, 1899: 8.

13 Ibid.

14 “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, May 7, 1900: 5.

15 “Boston Blue,” Sporting Life, September 16, 1899: 10.

16 “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, June 23, 1900: 4.

17 “Players Organize,” Sporting Life, June 16, 1900: 4.

18 Ibid.

19 “Finely Shaped Up,” Sporting Life, August 4, 1900: 5.

20 “Players’ Points,” Sporting Life, December 29, 1900: 2.

21 “Clarke Cheerful,” Sporting Life, January 27, 1901: 5.

22 “Baltimore Bulletin,” Sporting Life, March 2, 1901: 5.

23 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, March 23, 1901: 3

24 “New York News,” Sporting Life, April 29, 1911: 19.

25 Ibid.

26 “Baseball 2016 Record Book,” goprincetontigers.com/documents/2017/3/2/BASE_Record_Book_2016.pdf.

27 “150 Years – Baseball,” goprincetontigers.com/news/2014/11/22/209777562.aspx?path=baseball.

28 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, September 23, 1911: 13.

29 “Baseball History Up–to–Date,” Baseball Magazine, July 1918: 279; “A Letter from Aix–les–Bains,” Baltimore Sun, May 19, 1918: 15; Biographical Questionnaire for Princeton Coaches, Princeton University Library.

30 William J. Clarke and Fredrick T. Dawson, Baseball: Individual Play and Team Play in Detail (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915). books.google.com/books?id=BrRHAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PR3&ots=jbajYtmJBM&dq=Baseball%2C%20individual%20play%20and%20team%20play%20in%20detail%2C%20by%20W.%20J.%20Clarke%20…%20and%20Fredrick%20T.%20Dawson%20…%20with%20illustrations%20and%20diagrams.&pg=PR3#v=onepage&q&f=true.

31 Clarke and Dawson, v, viii.

32 Super Sports Feature on Bill Clarke.

33 “Baseball 2016 Record Book,” goprincetontigers.com/documents/2017/3/2/BASE_Record_Book_2016.pdf.

34 Clinton W. Blume to William J. Clarke, March 24, 1958, William J. Clarke, Faculty and Professional Staff files, Princeton University Library.

35 Bushnell, “Bill Clarke’s 90th Birthday.”

36 Ibid.

37 George H. Sibley to William J. Clarke, August 3, 1944, William J. Clarke, Faculty and Professional Staff files.

Full Name

William Jones Clarke http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

October 18, 1868 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

July 29, 1959 at Princeton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.