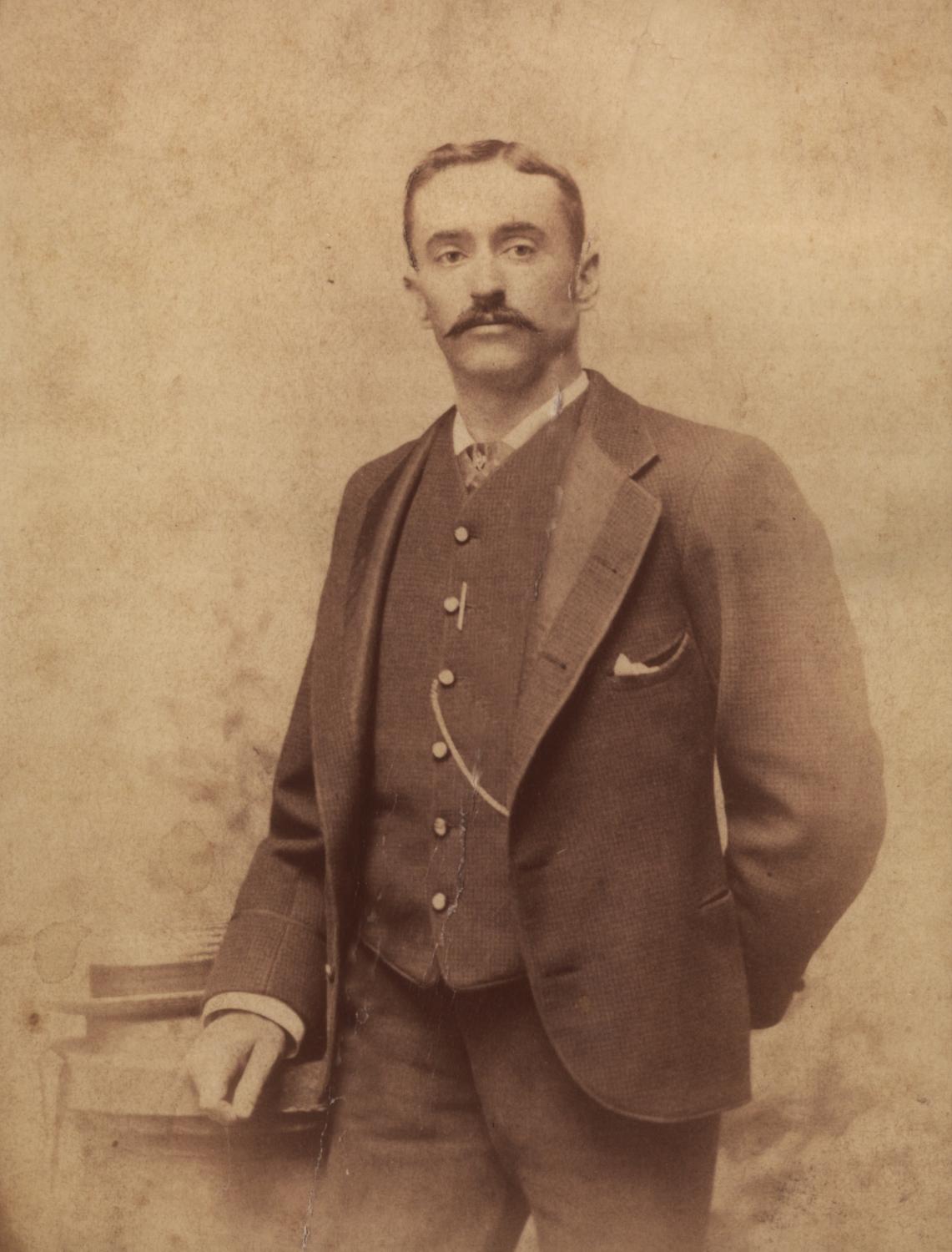

Ned Hanlon

Ned Hanlon managed 19 seasons in the major leagues — 12 in the 19th century, when he compiled a .586 winning percentage, and seven in the Deadball Era, when his winning percentage fell to .449. “Foxy Ned” guided five National League pennant-winners, the 1894-95-96 Baltimore Orioles and the 1899-1900 Brooklyn Superbas, but never finished higher than second in the Deadball Era. Some say that by that time the game had passed him by, but another possible explanation for his lack of Deadball Era success is that he was focusing most of his attention on returning big-league baseball to his beloved Baltimore.

Ned Hanlon managed 19 seasons in the major leagues — 12 in the 19th century, when he compiled a .586 winning percentage, and seven in the Deadball Era, when his winning percentage fell to .449. “Foxy Ned” guided five National League pennant-winners, the 1894-95-96 Baltimore Orioles and the 1899-1900 Brooklyn Superbas, but never finished higher than second in the Deadball Era. Some say that by that time the game had passed him by, but another possible explanation for his lack of Deadball Era success is that he was focusing most of his attention on returning big-league baseball to his beloved Baltimore.

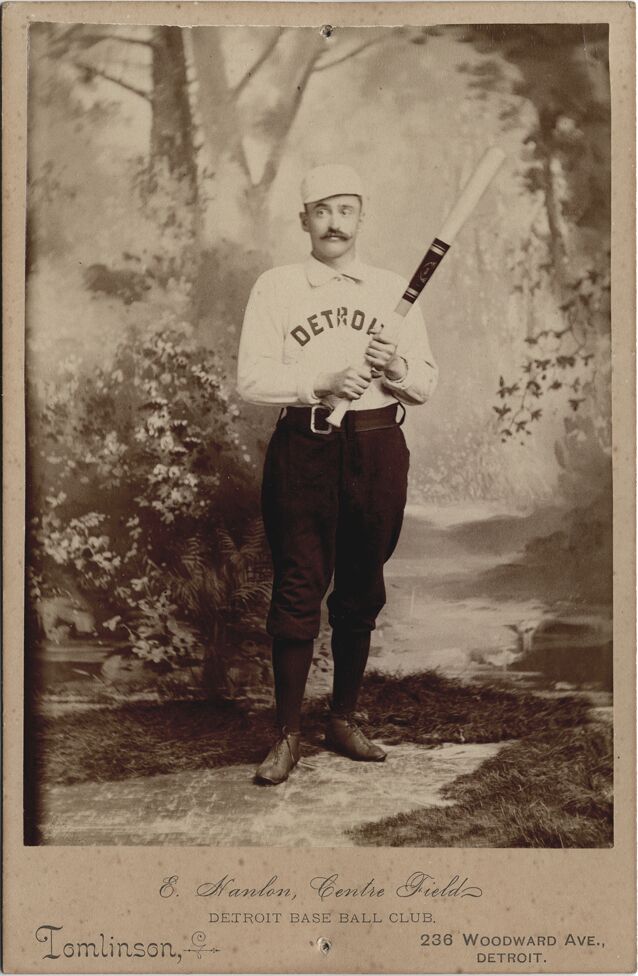

The son of a house builder, Edward Hugh Hanlon was born on August 22, 1857, in Montville, Connecticut, then a town of 1,800 citizens approximately halfway between New London and Norwich. A speedy center fielder who excelled on defense, Ned reached the big leagues in 1880 with the NL’s Cleveland Blues. In 1881 the lifetime .260 hitter began an eight-year stint with the NL’s Detroit Wolverines, posting his most successful season in 1887 when he hit .274 with a career-high 69 stolen bases and captained a team that became world’s champions. After the Wolverines disbanded, Hanlon joined the NL’s Pittsburgh Alleghenys in 1889, eventually being named the team’s third manager of that season. He showed a glimpse of his talent for leadership by posting a 26-18 mark with a team that finished with an overall record of 61-71.

Hanlon was active in the players’ Brotherhood, joining Detroit teammate Dan Brouthers and Brotherhood president John Montgomery Ward in 1886 to form a triumvirate to negotiate with the National League’s owners. Following the 1888 season, Ned and other major leaguers embarked on a world tour led by A. G. Spalding. While the players were in Egypt, they learned that the owners had adopted the Brush Classification Plan, limiting player salaries to $2,500. When the owners refused to back down, the players decided to form their own league. Hanlon was one of the first to jump to the Players League, serving as player-manager of the Pittsburgh Burghers in 1890. When the PL folded, he became player-manager of the National League’s Pittsburgh franchise, now called the Pirates. When Hanlon got off to a 31-47 start in 1891, the Pirates demoted him to captain and named Bill McGunnigle as the new manager. Ned suffered a late-season knee injury that marked the end of his career as a regular player.

The 34-year-old Hanlon was out of baseball when Harry von der Horst, the son of a wealthy Baltimore brewery owner, signed him in June 1892 to manage the NL’s Orioles, giving him stock in the team and full authority over baseball operations. Ned moved his growing family to a house that stood a block away from Baltimore’s Union Park. Though he told his new players that they had enough talent to win, by the end of 1893 only three remained on the roster: the battery of Sadie McMahon and Wilbert Robinson and young infielder John McGraw. After finishing dead last in a 12-team league in 1892, Hanlon traded for outfielders Steve Brodie, Willie Keeler, and Joe Kelley (acquired late in the 1892 season), shortstop Hughie Jennings, and first-baseman Dan Brouthers. He also acquired second-baseman Heinie Reitz and catcher Boileryard Clarke from the California League. In little more than a year “Foxy Ned” had given his team a complete makeover.

With his players’ rowdiness and his frequent use of the hit-and-run, the double steal, and the “Baltimore Chop,” Hanlon’s Orioles both intimidated and out-thought their opponents. They won NL pennants in 1894 and 1895 but were defeated in the Temple Cup Series (a short-lived series between the league’s two top finishers) by the New York Giants and Cleveland Spiders. Baltimore won a third consecutive pennant in 1896 and this time swept Cleveland to capture the Temple Cup. Though the Orioles finished second in 1897, they took the last Temple Cup series, defeating the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters.

With his players’ rowdiness and his frequent use of the hit-and-run, the double steal, and the “Baltimore Chop,” Hanlon’s Orioles both intimidated and out-thought their opponents. They won NL pennants in 1894 and 1895 but were defeated in the Temple Cup Series (a short-lived series between the league’s two top finishers) by the New York Giants and Cleveland Spiders. Baltimore won a third consecutive pennant in 1896 and this time swept Cleveland to capture the Temple Cup. Though the Orioles finished second in 1897, they took the last Temple Cup series, defeating the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters.

At a meeting of National League owners in February 1899, Hanlon and von der Horst swapped stock in the Baltimore franchise to Brooklyn owners Gus Abell and Charles Ebbets for stock in the Brooklyn franchise, with von der Horst gaining a controlling interest in both teams. Hanlon became manager of the Brooklyn club, taking Keeler, Kelley, Jennings, and several other Oriole stars with him. Hanlon’s Brooklyn squad, known as the Superbas after the vaudeville troupe Hanlon’s Superbas, won NL titles in 1899 and 1900. “Those old Baltimore Orioles didn’t pay any more attention to Ned Hanlon than they did to the batboy,” said Sam Crawford. “When I came into the league, that whole bunch had moved over to Brooklyn, and Hanlon was managing them there, too. He was a bench manager in civilian clothes. When things would get a little tough in a game, Hanlon would sit there on the bench and wring his hands and start telling some of those old-timers what to do. They’d look at him and say, ‘For Christ’s sake, just keep quiet and leave us alone. We’ll win this ball game if you only shut up.’”

Meanwhile, Baltimore was contracted out of the NL after finishing fourth in 1899. In 1901 the American League moved in, installing old Oriole John McGraw as manager of the new major-league Orioles. Withstanding mass defections to the AL, Hanlon kept his plucky Superbas near the top of the standings in 1901 and 1902, but his heart remained in Baltimore. When the Orioles left Maryland after the 1902 season to re-locate to New York City and become the Highlanders, Ned purchased the Eastern League’s Montreal Royals and moved the team to the now-vacant American League Park, which he bought for $3,000 after it had cost $21,000 to build only two years earlier. (He also owned Union Park, but it was in disrepair after several years of abandonment.) Hanlon installed old Oriole Wilbert Robinson as player-manager of the new minor-league Orioles, and sent another old Oriole, Hughie Jennings, down from Brooklyn when the team got off to a rough start.

The Superbas fell to fifth in 1903 after Keeler jumped to the AL — to the Highlanders of all teams — and that off-season Hanlon saw a great opportunity. The stock market had been unkind to von der Horst, forcing him to sell off his ownership interest in the Superbas, and Ned wanted to purchase the stock and move the team back to Baltimore. By that time, however, von der Horst was content living in Brooklyn, and Charles Ebbets arranged for him to sell to local interests (himself included). Hanlon, who had turned down many lucrative offers to manage elsewhere over the years, felt that von der Horst had betrayed his loyalty. To make matters worse, Ebbets informed him that his salary was being lowered from $11,500 to $7,500. Despite his pledge that 1904 would be his last season in Brooklyn, Hanlon guided the Superbas to a dismal 56-97 record that season, then returned in 1905 to top the century mark in losses.

In 1906 Hanlon became manager of the Cincinnati Reds, replacing his old Oriole star Joe Kelley, but still he dreamed about bringing big-league baseball back to Baltimore. He also felt he had a score to settle with Charles Ebbets. One month after the 1906 season, Hanlon filed two lawsuits. The first claimed that Ebbets and secretary-treasurer Henry Medicus received greater salaries than the Brooklyn club’s constitution allowed, and also charged them with violating Section 43 of the New Jersey Corporation Act, which required them to notify the secretary of state of their annual gathering. Because violators of Section 43 couldn’t hold the position of director, Hanlon anticipated that he and Gus Abell would fill the void, allowing him to move the Superbas to Baltimore. His second lawsuit called for repayment of a $30,000 loan he had given the Brooklyn club. Hanlon’s resort to the legal system proved futile; the only satisfaction he received was $10,000 for the stock he still held in the Superbas.

The Reds finished sixth in 1906, giving Ned his third straight losing season. His enthusiasm for managing beginning to wane, and soon to celebrate his 50th birthday, a tired Hanlon was in Brooklyn in late July 1907 when he announced to the press that he didn’t intend to return to the Reds in 1908. After the season — the Reds again finished in sixth — he moved back to Baltimore where he still owned the Eastern League’s Orioles. In 1909 Ned sold the team and its ballpark for $70,000 to an investment group headed by his old player Jack Dunn, who had pitched for him with the 1899-1900 Superbas. With the arrival of a Federal League franchise in 1914, Hanlon declined office in the Baltimore Terrapins but became the club’s biggest individual shareholder. The Terps flopped and the league went defunct. After being denied the opportunity to buy the St. Louis Cardinals with the intention of moving the team to Baltimore, Hanlon and his partners sued organized baseball for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. In a landmark 1922 decision that hasn’t been overruled to this day, the US Supreme Court, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. authoring the opinion, held that baseball was not interstate commerce and was therefore exempt from regulation by acts of Congress.

Ned Hanlon spent the last 21 years of his life outside the national pastime, though he still showed up occasionally for events at Oriole Park, the re-christened American League Park that he used to own. In 1916 he joined the Baltimore parks board, becoming its chairman in 1931. Among his acts in that capacity was putting old Oriole Steve Brodie on the parks department’s payroll. Hanlon died in Baltimore at age 79 on April 14, 1937, and was buried in New Cathedral Cemetery, which became an eternal gathering place for old Orioles — John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson, and Joe Kelley also are buried there.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Edward Hugh Hanlon

Born

August 22, 1857 at Montville, CT (USA)

Died

April 14, 1937 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.