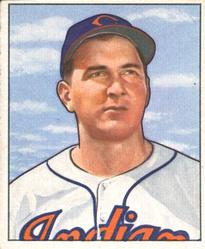

Allie Clark

What was Yankees manager Bucky Harris thinking? With his team leading the Brooklyn Dodgers, 3–2, with two outs in the sixth inning of Game Seven of the 1947 World Series, he sent rookie Allie Clark up to pinch-hit for rookie Yogi Berra. Out of context, given Berra’s Hall of Fame career, the move might seem puzzling. Allie Clark, called up from the Newark Bears in August, would never be a regular in his seven seasons with four different teams. But on this day Harris deemed him a better choice than Berra, and the move worked. Clark, who hit .373 (25-for-67) in the regular season, singled home Phil Rizzuto with the Yankees’ fourth run in a 5–2 victory. He replaced Berra in right field and was there when the Dodgers were retired in the ninth inning.

What was Yankees manager Bucky Harris thinking? With his team leading the Brooklyn Dodgers, 3–2, with two outs in the sixth inning of Game Seven of the 1947 World Series, he sent rookie Allie Clark up to pinch-hit for rookie Yogi Berra. Out of context, given Berra’s Hall of Fame career, the move might seem puzzling. Allie Clark, called up from the Newark Bears in August, would never be a regular in his seven seasons with four different teams. But on this day Harris deemed him a better choice than Berra, and the move worked. Clark, who hit .373 (25-for-67) in the regular season, singled home Phil Rizzuto with the Yankees’ fourth run in a 5–2 victory. He replaced Berra in right field and was there when the Dodgers were retired in the ninth inning.

Clark would later meet one of Berra’s sons at the Yogi Berra Museum in Montclair, New Jersey, and would tell the unbelieving young man that he once pinch-hit for his father. “He said, ‘No one ever hit for my father,’ but then he found out it was true. The box scores don’t lie,” said Clark. “It was the biggest thrill I had in baseball. The seventh game, there was a lot on our shoulders. We had to win, it was scary.”1

The crowd in Yankee Stadium that day was 71,528, though Clark’s wife Frances, who had been his high-school sweetheart, was not among them. Allie had assumed she did not want to attend the game and gave away the free passes he was allowed. Soon after the game ended, Clark called Frances at their home in South Amboy, New Jersey, and told her to meet him at a victory celebration that night at the Biltmore Hotel in Manhattan. “The one thing I remember most was Joe DiMaggio walking in with two girls under each arm,” she said in a 1999 interview.2

Clark’s pinch-hit single came in the last at-bat he had as a Yankee. That winter, the Yankees traded the six-foot, 185-pound outfielder to the Cleveland Indians for pitcher Red Embree. Because no one from the Yankees called Clark, he heard about the trade on the radio. More than six decades later, he still bristled at the memory. Though Clark lamented the trade to Cleveland, when the Indians won the 1948 World Series he became the first player win back-to-back World Series titles with different teams.

To get to the World Series in 1948, Cleveland had to win a one-game playoff at Boston’s Fenway Park. When Clark arrived at the park that day, he noticed a first baseman’s glove had been placed in his locker. There had to be a mistake, he thought, as he had never played first base in his professional career. “I asked [manager Lou] Boudreau, ‘What the hell’s this for? He said, ‘You’re playing first base.’”3 Boudreau told the right-handed-hitting Clark he wanted him in the lineup to take aim at Fenway Park’s left-field wall.

The experiment lasted only three innings. After the Indians took a 5–1 lead in the top of the fourth, Boudreau replaced Clark with Eddie Robinson. Clark, hitless in two at bats, had handled five chances flawlessly. When the move to Robinson was made, Clark recalled, “I was the happiest guy in the ballpark.”4 He earned faint praise from Rud Rennie of the New York Herald Tribune: “Clark played the position as one might expect it to be played by a man who never played it before. He did not drop any ball, but he always looked as if he might.”5

The Indians defeated the Red Sox, 8–3, and remained in Boston where they opened the World Series two days later against the Boston Braves. Clark played only in the second game, batting second and playing right field. His fifth-inning sacrifice against Warren Spahn led to a run in a 4–1 Indians victory. Frances Clark, who attended the games in Cleveland, said her biggest thrill as the wife of a baseball player was riding in an open car on Euclid Avenue in the victory parade.

Alfred Aloysius “Allie” Clark was born in South Amboy on June 16, 1923, the oldest child of Alfred and Helen Clark. Aside from the time he served in World War II and the summers he was playing professional baseball, he never left South Amboy, a small town at the mouth of the Raritan River, linked to New York by commuter trains and ferryboats. He attended Saint Mary’s High School, whose former students had five World Series rings as of 2011: two for Clark, two for Tom Kelly, who managed the Minnesota Twins to titles in 1987 and 1991, and one for Jack McKeon, who managed the Florida Marlins in 2003.

“South Amboy was a baseball-crazy town,” said South Amboy native Johnny O’Brien, who played six seasons in the National League in the late 1950s. “Every park where we went to play, people would point to spots way beyond the outfield fences and say things like ‘Allie Clark hit one way out there.’ That’s all you ever heard, things like ‘Allie hit a home run here.’ ‘Allie made a great play over there.’ You couldn’t help but want to become the next Allie Clark.”6

“We all have Allie to thank,” said McKeon, “He set the stage for all of us who followed. We all wanted to make it because he made it, so we ate, drank and slept baseball every day of our lives. No girls, no cars, just baseball.”7

“All we wanted to do was play ball. We made baseballs out of golf balls, wrapping them in black tape. If someone had white tape we were in hog heaven,” said Johnny O’Brien.8 The youth sports complex in South Amboy is named for Allie Clark, and until his health declined in 2011 he was present when the baseball season opened every spring. He lamented, however, that the number of players has declined, and when it is hot in the summer, boys are apt to be indoors playing computer games. “Kids aren’t playing ball every day like we did back then,” he said in 1999. “That’s why you see so many players from Latin America. They play ball like we did, growing up.”9

Clark was signed by the Yankees in 1941, receiving a bonus of $250. He split that year with farm teams in Amsterdam, New York, and Easton, Maryland, hitting a combined 334. In 1942 he batted .328 in 129 games for the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars of the Class B Piedmont League. One game that did not count in his official statistics was an exhibition against a team stationed at the US Navy base in Norfolk, where he faced Bob Feller. “I think he struck about eighteen of us out. He got me once.”10

Clark began the 1943 season with the International League Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm team. But midway in the season, he recalled, “Uncle Sam took care of me.” He was drafted into the Army and served as a combat medic for three years before being discharged before the 1946 season. “I was lucky I came out without a scratch,” he said.11

Two weeks after Clark was discharged the Yankees sent him a letter telling him to report to a Minor League camp in Sebring, Florida, where he was joined by future teammates Bobby Brown and Yogi Berra. “They still had [Charlie] Keller and [Tommy] Henrich and DiMaggio in the outfield, so they sent me down,” he remembered. “They kept Bobby Brown and Yogi. Then (in 1947) DiMaggio got hurt a little with the heel and they called me up.”12

Clark had proved he could hit at the highest level of the minors. In 1946 he hit .344 in ninety-seven games at Newark, with fourteen home runs and seventy runs batted in. He was batting .334 with twenty-three home runs and eighty-six RBIs in 1947 before his August call-up.

His first game was on August 5 against the Athletics in Philadelphia. He batted cleanup and played left field while the regular left fielder, Johnny Lindell, replaced Joe DiMaggio in center field. With the bases loaded, two outs in the top of the ninth and the scored tied 5–5, Clark had an infield hit to drive in the eventual winning run. The single, his first big-league hit, came off Russ Christopher. The next day, hitting cleanup again, Clark hit his first Major League home run off the Athletics’ Bill McCahan.

Clark lived at home that summer, commuting first to Newark and then the Bronx. Bobby Brown, who was living at the Jersey Shore, routinely drove Clark to Yankee Stadium. He said his Yankees teammates treated him well during the less than three months he spent on the team. One teammate, DiMaggio, remained aloof. “He never associated too much with the ballplayers. But he was a great ballplayer,” Clark said.13

Cleveland drew a league-leading 2,620,627 fans to Municipal Stadium in 1948, a record for the team at the time. “That town was wild about the Indians that year,” Clark said.14 Moreover, his roommate was second baseman Joe Gordon, his boyhood idol who had starred for the Yankees while Clark was in high school.

The 298 plate appearances in 1948 were the most Clark had in a season in a Major League career that also included stints with the Athletics (1951–1953) and the Chicago White Sox (1953). After the White Sox released him in June 1953, Clark signed with the St. Louis Cardinals’ organization. For five seasons he was a regular with the Cardinals’ International League affiliate, the Rochester Red Wings. As of 2011 he was seventh on Rochester’s all-time RBI list and tenth in base hits. “Rochester was a great baseball town,” said Clark, who was inducted into the Red Wings Hall of Fame in 1998.15 In 1958, after splitting the season with Minor League teams in New Orleans, San Antonio, and Indianapolis, he retired.

The player who once pinch-hit for Yogi Berra allowed that his game had one weakness. “I didn’t have a great arm,” he said, pointing to a scar on the inside of his right arm, the result of an operation he had at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore after the 1946 season. “They loosened up some tissue. I never should have had it done. That’s why I was never a regular [in the Major Leagues]. I didn’t throw very well.”16

While Clark was playing professional baseball he spent his off-seasons working with Local 373 of the Iron Workers Union in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. “I had to make money outside [of baseball] or we couldn’t get by. You ask any old-time ballplayer and they had jobs, working in stores, driving trucks, stocking stuff in warehouses, anything to support their families,” said Clark, whose peak salary in baseball was $11,000.17

Clark proudly wore his 1947 World Series ring at social occasions and on the job as an ironworker. Over time the diamond was dislodged and the words on the ring were worn so much that it was hard to read the inscription. It was hard to impress Little Leaguers when the words were blurred, but the city of South Amboy came to the rescue. The police department helped raise $2,500 to have the ring replaced. They contacted the Balfour Company, which made the ring, and with permission from the Yankees, Balfour replicated the 1947 World Series ring for Clark.

What Clark did not have in his possession were any game-used No. 3 Yankees jerseys. At the end of the season players were required to turn in their uniforms. After Clark left the Yankees, outfielder Cliff Mapes wore the iconic No.3. The number was retired at a 1948 ceremony that honored the original wearer of No. 3, the dying Babe Ruth.

Clark said taking a jersey at the end of a season was simply not done during his playing career. In the 1990s he attended an Old Timers game and the Yankees gave him a uniform with the No. 2, which he was allowed to keep. Times had changed. “When I played we had to buy our own gloves and spikes.”18

After he retired from baseball, Clark returned to South Amboy to work full time as an ironworker. He said he was proud of his work, having helped erect scores of buildings in Central New Jersey. “It was good steady work, outdoors, and I always enjoyed it. I was a strong guy and it didn’t bother me,” he said.19 Decades later he would feel the effects of heavy lifting with arthritis in his joints. He also survived bypass heart surgery and cancer.

In the spring of 2011 he said he knew of only three other members of the 1947 Yankees who were still alive: Bobby Brown, Yogi Berra, and pitcher Don Johnson. (Contrary to Clark’s recollection, Rugger Ardizoia and Dick Starr were also still alive.) Allie Clark died in South Amboy on April 1, 2012. His wife Frances, whose memory was robbed by Alzheimer’s disease, was living in a nearby assisted living facility.

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1. Home News Tribune, East Brunswick, New Jersey, October 15, 1999.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Author interview with Allie Clark, May 17, 2011.

5. New York Herald Tribune, October 5, 1948.

6. New York Times, October 11, 2010.

7. New York Times, October 11, 2010.

8. Home News Tribune, East Brunswick, New Jersey, February 2, 2003.

9. Home News Tribune, East Brunswick, New Jersey, October 15, 1999.

10. Clark interview.

11. Clark interview.

12. Clark interview.

13. Clark interview.

14. Clark interview.

15. Clark interview.

16. Clark interview.

17. Allen, Maury. Yankees: Where Have You Gone? Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004, pp. 106-107.

18. Allen, Maury. Yankees: Where Have You Gone? Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004, pp. 106-107.

19. Clark interview.

Full Name

Alfred Aloysius Clark

Born

June 16, 1923 at South Amboy, NJ (USA)

Died

April 2, 2012 at Morgan, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.