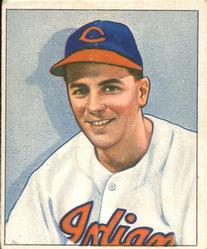

Lou Boudreau

In 1942, the Cleveland Indians chose their slow-footed, hard-hitting, slick-fielding 24-year-old shortstop Lou Boudreau to become player-manager of the ballclub. In his seventh season at the helm, he led the Indians to a World Series title. Perhaps the best shortstop of the 1940s and a great defensive player and batting champion, in that glorious season he also led by example, hitting .355 with 106 runs batted in. He did not have such a season again, but then again, not many people do.

In 1942, the Cleveland Indians chose their slow-footed, hard-hitting, slick-fielding 24-year-old shortstop Lou Boudreau to become player-manager of the ballclub. In his seventh season at the helm, he led the Indians to a World Series title. Perhaps the best shortstop of the 1940s and a great defensive player and batting champion, in that glorious season he also led by example, hitting .355 with 106 runs batted in. He did not have such a season again, but then again, not many people do.

Louis Boudreau Jr. was born on July 17, 1917, in Harvey, Illinois, to Louis Boudreau Sr., of French descent, and Birdie (nee Henry) Boudreau, of Jewish and German descent. Although his mother was Jewish, Lou and his older brother Albert were raised as Christians. His father was a machinist and a semipro baseball player.1

Lou’s father, a good third baseman for a semipro team in Kankakee, Illinois, instilled in Lou a gift for leadership, the drive to excel, and confidence in his ability. He would take young Lou Jr. out to the park and hit him 100 ground balls and count the errors he made. Lou’s parents were divorced when he was seven, and Lou split time with his parents thereafter. His mother married again, to a man who didn’t like sports and paid scant attention to Lou.

Lou went to Thornton Township High School, a school without a baseball team. Boudreau instead became a very good basketball player, an excellent passer and playmaker. At Thornton he met his wife-to-be, Della DeRuiter. They married in 1938.

In 1936, Boudreau entered the University of Illinois, where he majored in physical education and captained both the basketball and baseball teams. Boudreau led Illinois to the Big Ten basketball title in 1937, and was a 1938 All-American. Basketball took a huge toll on his ankles, eventually leading to arthritis. Lou had to tape them before every game of his baseball career. The ankles also earned him a 4-F classification during World War II.

As a college baseball player he averaged about .270 and .285. But all that practice with his dad fielding ground balls showed as he fielded his third base position excellently. The Cubs and Indians both pursued Boudreau and he also fielded offers to act in a movie and to play for $150 a game with Caesar’s All-Americans, a Hammond, Indiana, team in the National Basketball League, a forerunner of the NBA,. But Boudreau felt he owed his loyalty to Cleveland’s Cy Slapnicka, who had done his best to help him maintain his amateur status at Illinois.

The Indians assigned Boudreau in 1938 to a Class C club in the Western Association: he sat on the bench for a week and then was shipped to Cedar Rapids in the Class B Three-I League. After hitting .290 in 60 games, the third baseman was called up to the Indians. He sat on the bench observing Hal Trosky, Ken Keltner, Jeff Heath, Earl Averill, and a young pitcher named Bob Feller. Boudreau played first base and went to bat twice, grounding out and walking.

In 1939, Lou trained with the Indians in New Orleans. Manager Oscar Vitt advised Boudreau to move to the shortstop position, because young Ken Keltner looked to have a lock on third base. Ex-big leaguer Greg Mulleavy, the regular shortstop at Buffalo, was kind enough to take Boudreau under his wing and teach him the job. Lou batted .331 with 17 homers and 57 RBIs in 117 games , earning an August 7,recall to the parent club. Boudreau played 53 games at shortstop for the Indians in 1939, batting .258 with 19 runs batted in. Lou was now in the big leagues for good, but unfortunately lost his father that year. Lou Sr. never got to see his son play in the majors.

The 1940 season looked promising but would be tumultuous for the Cleveland Indians. Feller opened the season with a 1-0 no-hitter, and the Indians were in contention for the pennant all season long. But the season was marred by a rebellion of Cleveland ballplayers (not including Boudreau) who were unhappy with Vitt, who’d been known to bad-mouth his players with derogatory remarks. The 10 players, thereafter known as the “Crybabies.” complained to owner Alva Bradley in early June. Nothing was done and Vitt remained the manager for the rest of the season. The story hit the newspapers immediately, but the Indians continued to play well and went into Detroit on August 22 with a 5 ½ game lead over the second-place Tigers.

Boudreau kept his views to himself, but later wrote, “Had I been asked my opinion, I would have urged them to either wait till the end of the season, or to meet with Vitt himself and not with Bradley. But I wasn’t asked, I didn’t volunteer and the veterans did what they felt they had to do.”2 The Indians didn’t win the pennant that year, losing to Detroit by one game. Boudreau had a good season despite all the turmoil, batting .295, clouting nine homers, and driving in 101 runs. Defensively Lou led all shortstops in the American League.

In 1941, Lou was back at shortstop under popular manager Roger Peckinpaugh. Despite the switch, neither the Indians nor Boudreau fared as well as in 1940. Lou’s average fell to .257 with 10 homers and 56 runs batted in, though he led the league with 45 doubles.

After just a single season, Peckinpaugh was promoted to general manager and while a search was underway for a new manager, Lou sent a letter requesting an interview. On November 24, Lou presented his case. Initially, the vote was 11-1 against him, but George Martin, president of Sherwin Williams Paint Company, felt that a young man would be more desirable at this point than the tried and true. The directors finally agreed on Boudreau, backing him up with a staff of older and more experienced coaches: Burt Shotton, Oscar Melillo and George Susce.

Bradley introduced Lou to the press as the new manager, and one wag wrote, “Great! The Indians get a Baby Snooks for a manager and ruin the best shortstop in baseball.” The general feeling around the city was that Boudreau would not be able to handle both being a ballplayer and a manager, but the press was generally kind.

Soon after Boudreau’s hiring, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Two days later Bob Feller joined the Navy, and Boudreau, like his counterparts on the other teams, spent the next four years not knowing who their players were going to be. .

Not all of the Indians were happy with the new manager. During his first spring training, Boudreau had three players walk into his office (Ben Chapman, Gee Walker and Hal Trosky) to tell him they had asked for the job and could do a better job than he would. During some conferences on the mound, veteran pitchers would give Boudreau a variation of “Listen, college boy, you play shortstop and I’ll do the pitching.” Especially troublesome was Jim Bagby Jr., who Boudreau considered “the nastiest pitcher [I] ever played behind.” When Boudreau would boot a ball, he would hear razzing about going back to college to learn how to play shortstop.

Without Feller, the 1942 Indians went 75-79, 28 games behind the Yankees. Playing in 147 games, Boudreau batted .283, batting in 58 runs. Boudreau felt that the hardest part of his new job was having the sense of when to take a pitcher out. Though he was still learning, he proved able to manage the club and still play good ball at shortstop.

The 1943 club finished 82-71, still 15 ½ games out of first place at season’s end. Boudreau played in 152 games and batted .286 with 154 hits and 67 runs batted in. He led all league shortstops in fielding, and made his fourth All-Star team.

In 1944, the Indians slumped to 72-82, though Boudreau personally had a fine season, leading league batters at .327 and knocking in 67 runs. The next season he suffered a broken ankle and hit .306 in just 97 games, and the Indians finished 73-72. More importantly, the war ended in late summer, and Boudreau looked forward to the 1946 season and the return of real major-league ball.

With all the stars now returned to baseball in 1946, the fans turned out en masse. As usual Ted Williams was tearing up the league. The Indians went into Boston on July 14, for a doubleheader. In the opening game Boudreau went 5-for-5 with four doubles and a homer. Williams went 4-for-5 with three homers, all to right field. The Tribe lost the game, 11-10. Between games Boudreau came up with the famous Williams shift. When Williams came to bat with the bases empty, Boudreau yelled, “Yo,” and all the fielders shifted to the right side of the field. Williams laughed, got back in the box, and promptly grounded out to Boudreau, playing in the second baseman’s position. It wasn’t the first time a shift had been employed, but against a star of Ted Williams’ magnitude, it captured attention. 3

The Indians went 68-86 in 1946. Boudreau hit .293, with 151 hits, six homers, and 62 runs batted in. On June 21, 1946, Bill Veeck became the principal owner of the Cleveland Indians, and vowed to make changes. The Tribe improved to 80-74 in 1947, and Boudreau batted .307, banging out 165 hits with four homers, and 67 RBIs. The nucleus was there and Bill Veeck turned loose his bloodhounds, sniffing out trades that would turn things around. First they acquired second baseman Joe Gordon from the Yankees, along with third baseman Eddie Bockman. The Indians added Gene Bearden to the pitching staff and Hal Peck to the outfield.

The Indians made history in 1947 by signing the American League’s first black ballplayer, Larry Doby. Doby had been a second baseman for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. Boudreau tried to defuse any tensions about a black ballplayer coming on the roster by personally taking Doby around the clubhouse and introducing him. Some shook his hand while others refused, but Boudreau tried to make Doby’s joining the team as painless as possible.

Veeck thought the Indians needed a new manager. After that year’s World Series, Veeck proposed a deal with the St. Louis Browns that involved Boudreau. Lou also told Veeck that were he deposed as manager he would not play shortstop and would request a trade. These rumors did not sit well in Cleveland, and Veeck received more than 4,000 letters protesting any change. The Cleveland News ran a front-page ballot to elicit fans’ opinions, and 100,000 responses ran 10-1 for Lou Boudreau. Veeck yielded.

Boudreau and Veeck reconciled, and Lou was set as manager for the 1948 season.

Boudreau was upbeat about the 1948 season but knew he had to produce a winner or his tenure as manager would be up. The Indians remained in or near first place all season, locked in a tight three-team race with the Yankees and Red Sox. They added a new pitcher in July by the name of Satchel Paige, an aged but legendary hurler from the Negro Leagues. J. Taylor Spink, in The Sporting News, accused Veeck of signing Paige only as a publicity stunt. But Paige proved his worth, and eventually Spink apologized to Veeck. Boudreau used Paige sparingly as a starter and a reliever, and he had a 6-1 mark in the heat of the pennant race.

Boudreau experienced some hard times during the ‘48 campaign. Veeck had brought Hank Greenberg into the Indians organization to serve as Veeck’s right-hand man and confidant. This dismayed Boudreau, who at best never had Veeck’s ear, and now had to go through another channel before conferring with him. Greenberg and Veeck were always questioning Boudreau’s moves. Every morning during home stands Boudreau had to trudge up to Veeck’s office, where Veeck and Greenberg would fire questions at him. Even on the road he could not escape the telephone constantly ringing with questions from his two bosses.

Nothing was going to stop Boudreau from driving his team to the 1948 American League pennant, not even the plethora of injuries that befell him. During a hard collision at second base, Lou sustained a shoulder contusion, a bruised right knee, a sore thumb, and a sprained ankle. Managing from the dugout while icing down his injuries during a doubleheader against the Yanks, he watched the Indians fall behind, 6-1. The Indians bounced back and scored three runs to make it 6-4. The Indians then loaded the bases, and Lou called time. After selecting his bat he announced himself as a pinch hitter. Injuries or no injuries, he was going to take matters into his own hands. Boudreau ripped a single between the legs of Joe Page, tying the game. The Indians went on to sweep the doubleheader, 8-6 and 2-1.

As the season neared its end in 1948, Boudreau saw that some of his players were becoming a little too anxious. He feared that one or more of his players would say something in anger, sparking an incident that would upset the club. He asked reporters not to come into the clubhouse and they complied, showing the journalistic mores that existed at that time. Red Smith said that during the season “Boudreau managed like mad.”

At the conclusion of the 1948 schedule the Indians and the Red Sox were tied for first place. Some critics said that Boudreau could have avoided the need for a playoff game had he used Paige more, but instead a single-game playoff at Fenway Park determined the American League champion. Boudreau selected Gene Bearden start the game. Many question the choice of a left-hander in Boston with its looming left-field wall, but Boudreau felt that a knuckleball pitcher had a better chance against Boston’s powerhouse team. Feller called the decision “a stroke of genius and a shock to all of us.”

Boudreau took matters into his own hands and had a 4-for-4 performance that included two homers. When the final out was made and the Indians triumphed 8-3, Boudreau on his gimpy ankles rushed over to his wife. Bearden was on the shoulders of his mates, and, Bill Veeck, another casualty of World War II, hobbled out at top speed on his prosthetic leg to join the joyous mob. During his incredible season, Boudreau had slammed out 199 hits, belted 18 homers, and drove in 106 runs with a .355 average, all while guiding his team as manager. Boudreau was voted the Most Valuable Player in the American League in 1948.

The Indians capped off their 1948 season beating the Boston Braves and winning the World Series in six games. Boudreau batted .273 in the series with three runs batted in and fielded flawlessly. Lou Boudreau remains the only manager to win a World Series and win the Most Valuable Player Award in the same season.

Bill Veeck tore up Boudreau’s old contract and gave him a raise to $62,000 a year. Still, when the Indians failed to repeat in 1949, Boudreau knew his time was coming to an end. He felt that Hank Greenberg had a lot to do with his fate as manager. Boudreau didn’t mind Greenberg’s second guessing, but was upset that Greenberg never gave him reasons for disagreeing. Veeck was distant with Boudreau in 1949, never having much to say to him. Lou, playing all four infield positions, batted .284, with four homers and 60 RBIs.

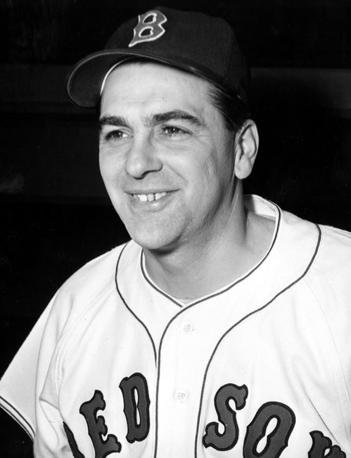

Lou’s last season in Cleveland was 1950. Playing in only 81 games, he batted .269, with just one homer. Ellis Ryan took over as principal owner from Bill Veeck and put Greenberg in charge. As expected, on November 10, the Indians released Boudreau after 12 years as a player and nine as manager. The Red Sox acquired him in 1951 as a utility infielder. Playing in 82 games, he batted .267, with five homers and 47 runs batted in. After the 1951 season, the Red Sox named Boudreau manager. He played four games for the club in 1952, but was a bench-manager for the rest of his career.

Boudreau managed the Red Sox from 1952 through 1954, an event-filled period for the franchise. The team had spent a lot of money on amateur players in recent years, and Boudreau presided over the transition. Bobby Doerr had recently retired, Johnny Pesky and Vern Stephens were traded, and Ted Williams spent most of two seasons in the Marines In the spring of 1953 center fielder Dom DiMaggio suffered an eye injury and was replaced by Tommy Umphlett; when Umphlett got hot, DiMaggio stayed on the bench. DiMaggio was unhappy, but Lou felt that he had slowed down and was letting too many balls drop-in center field. DiMaggio retired and remained bitter at Boudreau for the rest of his life.

Boudreau managed the Red Sox from 1952 through 1954, an event-filled period for the franchise. The team had spent a lot of money on amateur players in recent years, and Boudreau presided over the transition. Bobby Doerr had recently retired, Johnny Pesky and Vern Stephens were traded, and Ted Williams spent most of two seasons in the Marines In the spring of 1953 center fielder Dom DiMaggio suffered an eye injury and was replaced by Tommy Umphlett; when Umphlett got hot, DiMaggio stayed on the bench. DiMaggio was unhappy, but Lou felt that he had slowed down and was letting too many balls drop-in center field. DiMaggio retired and remained bitter at Boudreau for the rest of his life.

Boudreau also chose to move promising rookie Jimmie Piersall from the outfield to shortstop in 1952, a shift that Piersall later claimed led to bizarre behavioral problems and eventual nervous breakdown. When Piersall recovered, Boudreau kept him in the outfield, and Piersall played another 15 seasons. Though the Red Sox posted a surprising 84-69 record in 1953, their regression the next year (69-85) led to Boudreau’s dismissal.

After being fired by the Red Sox in 1954, Boudreau got a job as manager of the Kansas City Athletics, a bad club recently transplanted from Philadelphia. He lasted three years at Kansas City; the team finished sixth once and eighth twice during his tenure.

Boudreau was fired in August 1957. Not long after, Jack Brickhouse approached Lou about being the color man for the Chicago Cubs broadcast team. He auditioned and got the job. Lou was no Demosthenes, and he stumbled over difficult names of players, but his knowledge of the game and his uncanny ability to anticipate what would happen in certain situations was noted. For over two years Boudreau was the Cubs color man, but by 1960, Lou was back into the managing business for the team, while Charlie Grimm was shifted from skipper to the radio booth. A poor team, the Cubs finished in last place 35 games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1961, Lou was back in the broadcasting booth.

Della Boudreau stayed home and raised four children. Older son Louis joined the Marine Corps and was wounded in Vietnam. James was a fairly good left-handed pitcher who played in the minors but hurt his arm and gave up baseball. Lou’s daughter Sharyn married Tigers pitcher Denny McLain, who had numerous legal troubles during after his career, including two stints in prison. Older daughter Barbara married Paul Golazewski, a former quarterback at Illinois.

Lou was a part of the Cubs broadcast team for 30 years. When the station chose not to pick up his contract for the 1988 season, Lou was 71 years old, and finally retired, after having been a player, manager, and broadcaster for 50 years.

On July 27, 1970, Lou was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Bowie Kuhn, the Commissioner of Baseball, introduced Boudreau: “There are hitters in the Hall of Fame with higher batting averages, but I do not believe there is in the Hall of Fame a baseball man who brought more use of intellect and advocation of mind to the game than Lou Boudreau.”

Bob Feller, a close friend of Boudreau, said, “Boudreau was one of the most talented players in baseball in his time, in addition to being one of the classiest human beings you’d ever want to meet.” Feller added, “Even before he was manager, as a 21-year-old shortstop he was our on field leader. Boudreau drew people to him. He had the looks of a matinee idol.”

Lou Boudreau Jr. left his mark on baseball through his intelligence and innovativeness as a manager and by his sterling play at shortstop and his all-out competitiveness. He died in Frankfort, Illinois, on August 10, 2001, at age 84. Della had preceded him in death in 1999. Boudreau was survived by four children and 10 grandchildren. Lou Boudreau is interred in the Pleasant Hill Cemetery in Frankfort, Illinois.

Last revised: June 21, 2021 (zp)

Sources

Louis Boudreau and Russell Schneider, Covering All the Bases (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1993).

Gordon Cobbledick, “The Cleveland Indians” in Ed Fitzgerald, ed., The Book of Major league Baseball Clubs: The American League (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1952).

Robert Feller and Bill Gilbert, Now Pitching Bob Feller (New York: Citadel Press, 1990).

David Halberstam, Summer of ’49 (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1989).

Donald Honig, The American League: A Pictorial History (New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1983).

Peter S. Horvitz and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: S.P.I Books, 2001).

Franklin A. Lewis, The Cleveland Indians (New York: Putnam, 1949).

William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

Joseph Thomas Moore, Pride against Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988).

Red Smith, On Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000).

Notes

1 Most of the material from Boudreau’s early life is from Louis Boudreau and Russell Schneider, Covering All the Bases (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1993).

2 Boudreau and Schneider, 28.

3 Though the Williams shift was a success, its origins are unclear. In Great Baseball Feats, Facts and Firsts, David Nemec says it was used against another player named Williams, Ken Williams of the St. Louis Browns. Rob Neyer argues that the shift was used some years earlier, against Cy Williams of the Phillies. And finally, Glenn Stout, editor of Great American Sportswriting, says that Jimmie Dykes, manager of the Chicago White Sox in 1941, was the first to use a shift against Ted Williams. In any case, left-handed-hitting Williamses seem to have cornered the market on shifts.

Full Name

Louis Boudreau

Born

July 17, 1917 at Harvey, IL (USA)

Died

August 10, 2001 at Olympia Fields, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.