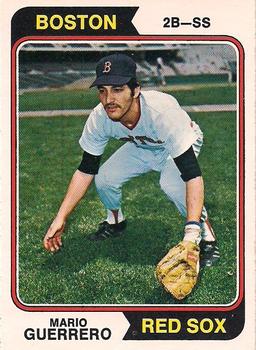

Mario Guerrero

Born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on September 28, 1949, Mario Miguel Guerrero Abud played over eight years as a shortstop and second baseman for four different teams. He was the younger brother of Epy Guerrero (born 1942), who is regarded as one of the greatest scouts in major-league baseball history and was responsible for signing 52 players who made big-league rosters.1

Born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on September 28, 1949, Mario Miguel Guerrero Abud played over eight years as a shortstop and second baseman for four different teams. He was the younger brother of Epy Guerrero (born 1942), who is regarded as one of the greatest scouts in major-league baseball history and was responsible for signing 52 players who made big-league rosters.1

Their parents were Epifanio Guerrero (after whom Epy was named) and Patria Abud. Their father ran a grocery business and cattle farm. There were five boys in the family. Mario attended Dominican College and La Salle College, both in the D.R. He was signed as an amateur free-agent teenager in 1968 by New York Yankees scout Dr. José “Pepe” Seda.

That first year, 1968, Guerrero played shortstop in the Single-A Florida State League for the Fort Lauderdale Yankees. He appeared in 91 games, struggling a bit, committing 25 errors in 330 chances (a .924 fielding percentage) while batting .227. He drove in 14 runs and scored 28. One of his 72 base hits was a home run, one was a triple, and five were doubles. He drew 21 walks but struck out 30 times. The Yankees placed him at Single A again in 1969, with the Kinston Eagles (Carolina League). He played in 132 games and hit for a much-improved .282 batting average, driving in 46 runs, and was named to the league All-Star team. His fielding percentage was a bit lower (.919).

He had an exceptional year in Dominican Winter League ball. He’d played briefly for Tigres de Licey in 1967-68 and in 1968-69. In the 1970 season he played his first nine games for the Tigers and then moved on to the Leones del Escogido, batting .308 in 26 games, and then hit .391 in the Final Series, playing for manager Tommy Lasorda.

The Yankees elevated him to the Double-A Eastern League in 1970. For the Manchester (New Hampshire) Yankees, Guerrero hit .241 over 139 games. In late December 1970, he married Teresa Lama. Their first-born child was named Mario Miguel Jr. — “Mickey,” which Guerrero reported had been his nickname in baseball.2 He has two other sons, Benjamin and Jesse.3

In 1971 he was promoted once more, this time to the Triple-A Syracuse Chiefs (International League). Even though he was at a higher level, he improved his average to .290 (.329 OBP) and his fielding improved a bit, too.

In March 1972, the Yankees pulled off a rare trade with the rival Red Sox and acquired reliever Sparky Lyle in exchange for Danny Cater and a player to be named later. On June 30 that player was finally named: it was Mario Guerrero. He’d begun the season with Syracuse, but now Boston assigned him to their own Triple-A Louisville Colonels. He hit .280 in 62 games for the Chiefs, and .301 in 69 games for the Colonels, and was named the International League’s All-Star shortstop. He then played winter ball in the Dominican Republic and hit .300. Guerrero frequently played winter ball, for nine years in a row from 1968 through 1976, and then in 1979, 1980, and 1984. All told, he played in 382 Dominican Winter League ball and had an overall .293 career batting average with 117 runs batted in.

Guerrero didn’t show up for spring training in 1973 until the second week of March. He said he’d never received a telegram inviting him. “Guerrero couldn’t understand why he hadn’t heard from us,” said manager Eddie Kasko on March 5. “There must have been a mixup.”4 Once he arrived, he had a good spring. He was the backup and heir apparent, to Boston’s 39-year-old Luis Aparicio.5 He made the team as a utility infielder, and enjoyed his major-league debut on April 8. The Red Sox were hosting the Yankees at Fenway Park. He entered the game after the third inning, replacing Aparicio, who had gotten some dirt in his eye. Guerrero grounded out to the pitcher his first time up, but hit an infield single and later scored his second time up. He hit yet another infield single in the eighth, leaving him 2-for-3 in his first game. He also committed two errors in the game. The Red Sox won, 4-3. Guerrero was 1-for-3 in his second game, on April 22. His first big thrill came in the bottom of the 11th inning of the May 14 game against the Baltimore Orioles. The game was scoreless. Guerrero singled to lead off. Carl Yastrzemski sacrificed to send him to second, and he scored the winning run when Orlando Cepeda singled to center field.

On June 2, Guerrero tied a major-league record for shortstops by participating in five double plays. Kasko was impressed with his shotgun of an arm: “He takes his time and really pops the ball.”6 In the June 19 doubleheader in Milwaukee, he was 6-for-11 and “started the tying rallies in both games and the winning one in the opener and had a couple of plays at short that make you wonder how he can ever return to the bench.”7 He stuck with the Red Sox all season long, appearing in 66 games and accumulating 233 plate appearances. He hit for a .233 batting average (.272 on-base percentage), with 11 RBIs and 19 runs scored.

In 1974, under new manager Darrell Johnson, Guerrero got a lot of work at shortstop. He appeared in 93 games, batting .246 (.282 OBP), with 23 RBIs and 18 runs scored. His fielding was fine, after those debut day jitters the year before. In the rest of 1973, he only committed three more errors and in all of 1974 he only committed three. He strained his knee badly in mid-July and from the 20th to September 2 only played one full game and part of another. Rick Burleson, who had been optioned to Pawtucket at the start of the season and then brought back at the start of May, filled in, came on strong, and ultimately played in even more games than Guerrero. Burleson hit .284, placing fourth in Rookie of the Year voting.

It was unclear to at least some in Boston if Guerrero would come to spring training in 1975. “He said last fall he might quit baseball for a musical religious sect in the Dominican Republic,” wrote Ernie Roberts, “and he disappeared from his Santo Domingo nine during this winter season.”8 Newspapers reported he hadn’t come to terms with the Red Sox and that he was the first “holdout” on the Sox for 18 years.9 He arrived on March 4, unannounced. Not appearing to be in Boston’s plans, he took his gear out of the clubhouse a few weeks later, demanded a trade, and said he was returning home. He returned a couple of days later, but was placed on waivers on March 29. On April 4 he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for a player to be named later; the player turned out to be pitcher Jim Willoughby, who came to the Red Sox on July 4.

The Cards placed Guerrero with their Triple-A team, the Tulsa Oilers. He hit .278 in 31 games for the Oilers. On May 21 he was brought up to the big-league club, joining the Cardinals in San Diego. He was 2-for-3 in his first game, and .324 by the end of May. By season’s end, he’d appeared in 64 games for St. Louis, hitting .239. He drove in 11 runs and scored 17.

He started the 1976 season with Tulsa and was hitting .235 in 29 games when he was traded to the California Angels for a minor leaguer and another minor-league player to be named later. It was the last time he ever played minor-league ball. On June 2 he started playing for the Angels, but only pinch-ran or came in as a late-inning defensive replacement for his first several games. His first at-bat resulted in a hit and he collected a hit in each of the first five games in which he did get an at-bat. Again, he started strong in his first month, hitting .328 at the end of June. This year, however, he hit quite well all year long, finishing with a mark of .284. He got his first home run on August 19 in Detroit; Guerrero hit seven homers in the majors. In 83 games, he only drove in 18 runs.

The 1977 season was more or less a carbon copy of 1976 in some regards — 86 games, with a .283 batting average, but he drove in 28 runs. He became a free agent at the end of the 1977 season and signed with the San Francisco Giants on December 15.

Guerrero never played for the Giants, though. Days before the season opened, he was the player to be named later in a deal that had already sent six players and $300,000 cash to the Oakland A’s so the Giants could secure pitcher Vida Blue. He had his best year in the big leagues in 1978, playing 143 games and driving in a career-best 38 runs. He hit .275 (.302 OBP). He made the difference in a few games, driving in three runs in the 4-2 win over the Angels on April 8. On April 29 he drove in four as Oakland beat Cleveland. On July 5 his two-run home run in the top of the ninth produced a 5-3 win over Seattle at the Kingdome.

In 1979 he only got into 43 games. Manager Jim Marshall simply didn’t use him much, favoring Rob Picciolo at shortstop. Guerrero’s first game was April 25. He was not used for most of the second half of June, and then didn’t play at all from June 30 until August 23. He was not pleased at not being played, and reportedly stated he would “not play again for the team because he is not starting.”10 He’d been seen during games standing in the tunnel, and not in the dugout, dressed not in full uniform but wearing just a t-shirt under his A’s jacket.11 After the 31st of August, he only appeared in one game. There may have been some injuries as well, but some reporters were skeptical in that regard.

When Billy Martin came in to take over as manager in 1980, a UPI article in early March quoted Guerrero as saying of Martin, “He’s changed my attitude. I’ve got to forget everything from last year.” The article said that Guerrero had spent “most of the 1979 season idled by injuries, some of which were imagined.”12 Another UPI story said that Guerrero was in a feud with Jim Marshall and “flat out refused to play after June last year, claiming injury while in fact he was sound. Then, Charlie Finley ordered Marshall not to play Guerrero no matter what.”13

Guerrero’s final season in the majors was 1980. He played in 116 games, all at shortstop, for Oakland, batting .239 with 23 RBIs. The A’s finished in second place, 14 games behind the Kansas City Royals.

It was a good enough season on paper, but the A’s were not sufficiently impressed and placed Guerrero on waivers. The following May, Oakland coach Clete Boyer said, “We’re better off at shortstop because we don’t have Mario Guerrero. He didn’t fit in as a team player.”14 The Seattle Mariners purchased Guerrero’s contract in December and he signed a one-year deal with the Mariners in February. Mariners manager Maury Wills said, “Mario just had a little personality conflict with Billy Martin. But you know that can be understood.”15 Nonetheless, Guerrero was released on April 1, near the end of spring training in 1981. He was batting .268 in 12 games. “From the standpoint of ability,” wrote the Seattle Daily Times, “Guerrero was considered the best shortstop in camp here. However, Mario, as he has done before, proved incompatible with his superiors.” Guerrero said, “I make a lot of money and this club is not a contender. I will try to play somewhere else.”16

He did not succeed that year. In early 1982 there was a report that he had requested a tryout with Toronto. Nothing seemed to come of that. In September it was reported that he was working as a player agent, working primarily in Southern California but with, “as yet…no big-name clients.”17

In 1981, Epy Guerrero had opened the Epy Guerrero Sports Complex in Villa Mella, about a dozen miles from Santo Domingo. In 1986, Bill Brubaker reported regarding the self-contained complex: “When Epy is scouting, the camp is operated by his younger brother, former major league shortstop Mario Guerrero.”18 He quoted Mario as saying, “I go over there almost every day and help with the kids. I teach them how to take ground balls, how to throw, how to hit. That way, I see the kids every day, and when they’re big, they maybe won’t forget me, and they’ll stay with me.”

Brubaker added, “By ‘stay with me,’ Guerrero means ‘sign with me.’ Mario Guerrero is a player agent, which makes his presence at the Blue Jays’ camp questionable at best.

“When I retired from baseball, agents began calling me, asking if I wanted to work for them,” Mario Guerrero explained. “They knew I had played a lot of games in the big leagues and, besides that, they knew that Epy and me are really close and he always has some good players like Tony Fernandez.

“In 1981, I told Epy, ‘I’m going to be an agent. I want the players [from the Blue Jays’ camp].’ And he told me, ‘Yeah, we’re together. I’ll give them to you, but don’t take over until they get to the big leagues.’ “

The story continues: “Mario Guerrero said that from 1981 until 1984, he worked as a recruiter for a U.S.-based sports agency. ‘I introduced this company to a lot of players in the Dominican Republic.’ They signed a lot of the players, and they agreed to give me a percentage of their fees. But they never did.’

“In 1984, Guerrero said, he decided to open his own agency. His most prominent client was [Tony] Fernandez, who recently explained, “I went with Mario because he was Epy’s brother. I thought, ‘Epy has given me the chance to be a pro player, so why not give Mario the chance to be the agent?’ “19

In January 1986, Mario Guerrero took a position as a recruiter with Davimos Sports Management Inc., of Boca Raton. “I decided to go with them because I needed the check,” he said.20

In 1987 the San Francisco Chronicle also identified Guerrero as a “player agent.”21

At the end of the 1980s, Guerrero resurfaced again in professional baseball, playing in the Senior Professional Baseball Association. He was 39 years old, young for the league, but made the cut. He played for the Winter Haven Super Sox and hit .315 in 15 games.

Years later, Guerrero was in the press again due to a protracted courtroom battle with ballplayer Raul Mondesi. When Mondesi was a young teenager, he purportedly was tutored by Guerrero and in turn promised him to give him 1% of any major-league earnings. In 2004, Guerrero said he still worked out ballplayers at a field near his home in the Dominican Republic to try to help them get signed, but that he additionally provided “special tutoring” to players already in the majors. That’s what he said he had done with Mondesi.22 In 1998, Guerrero had filed a suit against Mondesi seeking the compensation. He admitted there was no written agreement. In 2002 the suit was dismissed for that very reason, but he filed a civil case in November 2003 and the Court of First Instance in the Dominican Republic ruled in his favor, calling for more than $1,000,000 in earnings and interest to be paid to Guerrero.

Guerrero asserted that a number of other ballplayers, including Tony Fernandez, Pat Borders, and Francisco Cabrera had already paid him similar moneys, and in October 2003 he also won a $163,000 judgment against Geronimo Berroa. The controversy created strong feelings among Dominican ballplayers. In an interview with Listín Diario, George Bell said of Guerrero, “Mario Guerrero doesn’t have friends. He is a slickster who is doing enormous damage to those players.” Guerrero said that people were warning him that his safety might be in jeopardy: “Watch out. Watch out.”23

Mondesi appealed the ruling, but his accounts were frozen. He said he was “fearful for his family’s safety” in the Dominican Republic.24 He left the Pirates to return home, initially granted a leave. But when he did not return the Pirates let him go, placing him on waivers and releasing him.25

It is not clear how the case may have been resolved, but Mondesi’s career never got back on track, and ended the following year. He later went into politics, became the mayor of San Cristobal, and in September 2017 he was sentenced to eight years in prison for embezzling more than $6 million.26

That unpleasantness aside, Mario Guerrero has, since 1989, lived near Santo Domingo, in the El Mirador area, and run small camps where he helps teach young Dominicans about baseball.

Last revised: December 26, 2018

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Guerrero’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 For more on Epy Guerrero, read Jim Sandoval’s “Epy Guerrero: Super Scout,” in Can He Play? A Look At Baseball Scouts and Their Profession, edited by Jim Sandoval and Bill Nowlin (SABR: Phoenix, 2011).

2 Mario Guerrero player questionnaire completed for, and on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

3 Email to author from Mike Guerrero, November 27, 2018.

4 Clif Keane, “’It Will Take Time — Cepeda,” Boston Globe, March 6, 1973: 30.

5 Harold Kaese, “Guerrero Figures To Stay Put,” Boston Globe, March 22, 1973: 49.

6 Neil Singelais, “Guerrero Gets the Job Done — But It’s Only Temporary,” Boston Globe, June 5, 1973: 44.

7 Peter Gammons, “Pattin, Curtis Lift Sox, 8-4, 4-1,” Boston Globe, June 20, 1973: 65.

8 Ernie Roberts, “Did Guerrero Get Religion?” Boston Globe, March 1, 1975: 17.

9 UPI, “Yaz, Tiant Battle Back Ailments,” Nashua Telegraph, March 3, 1975: 18.

10 AP, “Woeful A’s Swallow More Bad News,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, July 10, 1979: 7.

11 AP, “Texas Hands A’s Double Loss; Altercation Brews,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, June 25, 1979: 8. Miguel Dilone was also spotted “keeping away from the dugout.”

12 “Martin’s A’s Begin to Believe,” Ukiah Daily Journal, March 5, 1980: 6.

13 UPI, “Oakland’s Rob Picciolo,” Galveston Daily News, March 26, 1980: 16.

14 NEA, “A’s May Be Ready to Fold Due to Infield,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune (Logansport, Indiana), May 3, 1981: 20.

15 AP, “Wills Knocks Martin,” Syracuse Herald-Journal, January 28, 1981: D-6.

16 “Diamond Dealings: Mariners Waive Mario Guerrero,” Seattle Daily Times, April 1, 1981: 39.

17 “Giants,” Sacramento Bee, September 14, 1982: 24.

18 Bill Brubaker, “The Envy, and Scourge, of the Latin Scouts, Epy Guerrero Gives Blue Jays an Invaluable ‘In’,” Washington Post, February 4, 1986: B1.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 John Krich, “Land of A Thousand Shortstops,” Image (San Francisco Chronicle), March 22, 1987: 283.

22 Jeffrey Cohan, “Mondesi Still Stuck in Courtroom Mess,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 16, 2004.

23 Ibid.

24 “Sox Ready for Garciaparra’s Return,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 30, 2004: 34.

25 Murray Chass, “Mondesi’s Evolution From Pirate to Angel,” New York Times, June 1, 2004: D7.

26 Eric Nusbaum, “Raul Mondesi Sentenced to 8 Years in Prison in the Dominican Republic,” Vice Sports, September 17, 2017. https://sports.vice.com/en_us/article/d3y7m7/raul-mondesi-sentenced-to-8-years-in-prison-in-the-dominican-republic

Full Name

Mario Miguel Guerrero Abud

Born

September 28, 1949 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.