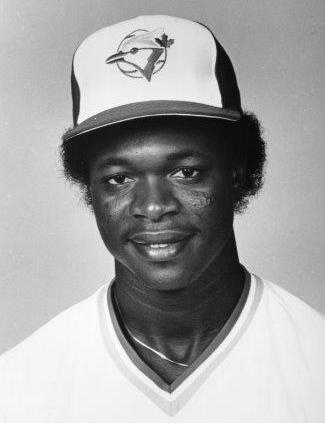

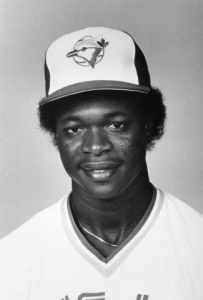

Tony Fernández

Tony Fernández was all limbs. At shortstop, the gangly fielder scuttled after groundballs before pirouetting to make an underarm throw with a slight flick of the wrist. At the plate, he slashed at the ball before scurrying around the bases.

Tall and lean at 6-feet-2 and 165 pounds, the infielder enjoyed a 17-season major-league career. He played in the postseason for three different teams and won a World Series championship in 1993 with the Toronto Blue Jays, the team that originally signed the impoverished teenaged amateur from the Dominican Republic. Along the way, he earned four consecutive Gold Gloves as the best-fielding American League shortstop, so good a player that his acquisition by the New York Yankees in 1995 delayed the ascension of top prospect Derek Jeter.

Fernández combated stereotypes in all his baseball stops. Some reporters, unwilling to acknowledge he was being asked to field provocative questions in a second language, thought him sullen and diffident. As a devout Christian, he eschewed the late-night revelry others thought helped a team bond. Though lacking a formal education, he was a wise analyst of what it meant to play professional sports in a foreign land in a foreign language where his ethnicity meant something different than it did back at home.

“Latin players have been misunderstood, made out to be moody, hostile, lazy, erratic,” Fernández said in 1992, by which time he was an established star. “We are an emotional people. But we are honest and sincere, and the difficulty of the change in cultures has just never ever been fully accepted and appreciated. Of course it all still hurts. But not as much as it used to.”1

Octavio Antonio Fernández Castro was born in San Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic, on June 30, 1962, to the former Andrea Castro and José Fernández, a man of Haitian descent born as a Fernando who took as his surname Fernández. He supported as best he could a family of 11 children (seven boys, four girls) as a cane cutter in the sugar fields. Baby Octavio’s hairless head was so outsized that his father dubbed him El Cabeza (The Head), a nickname that would stick through adolescence.

The boy’s arrival came a year after the assassination of the brutal dictator Rafael Trujillo, the leader of a cult of personality, who was known as El Jefe (The Boss). Trujillo used baseball as a means of expressing his nation’s – and, by his twisted measure, his own – glory. In the 1950s the government built a trio of stadiums modeled on Miami Stadium, where the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers and, later, the Baltimore Orioles trained each spring. One was constructed in the capital of Santo Domingo, a larger one in Santiago, and the third in San Pedro de Macoris, about 50 miles east of the capital.

The Fernández family lived just beyond the right-field fence of Estadio Tetelo Vargas, named for a star of Negro League and Caribbean baseball. The surrounding Barrio Restauracíon was a tough district of dirt roads with single-story shacks and shanties boasting tin roofs and no running water.

Like most of the other boys in the neighborhood, Fernández spent all his free time around the park, which was home to the Estrellas Orientales (Eastern Stars). He was among the urchins who would climb trees for a better unpaid view of a game, quickly scrambling down to pursue any ball hit in their direction. The boys played pelota with whatever was at hand – broken broom handle, rolled-up socks covered in tape, the occasional stray baseball. Sometimes his mother asked the boy to skip pickup games to push the family’s vegetable cart along the bumpy, dusty streets, a task for which his older brothers were too ashamed.

The boy also scrounged work at the stadium as a batboy, a groundskeeper, and as an all-around laborer, a skinny kid who could be pressed into service loading the team’s bus. Of course he shagged fly balls and chased groundballs with the eagerness of a pup. Early on, he showed soft hands, perhaps because he was too poor to afford a leather glove, instead using scraps of cardboard or a flattened milk carton tied to his left hand. He showed an adroit sense of the game obvious to any learned eye who saw him field on the uneven diamonds of the Dominican. At the same time, he was hobbled by a bone chip in his right knee. The nagging injury put him on the reject list for scouts and bird-dogs. The injured prospect was damaged goods, a tullido, a cripple, lame. His mother pestered a doctor in the capital who, after also being pressured and likely paid by one persistent scout, operated on the boy’s knee. The family was so poor the boy shared a hospital bed with another lad as he recuperated for six weeks.

Two years later, his legs still not at full strength, the still-growing teenager – as lean as a stalk of sugar cane at an even 6-feet and, 140 pounds – boarded a bus to the capital for a tryout in front of the scout. Epifanio “Epy” Guerrero, whose big break was signing César Cedeño to Houston, had since opened an academy for prospects a few miles outside Santo Domingo. By then working for the Blue Jays, Guerrero signed the 17-year-old Fernández, who had been a student at Gaston Fernando de Ligne high school, on April 24, 1979. Only after the money for his signing bonus arrived and the boy dumped a large pile of pesos on his mother’s bed did she fully appreciate that baseball was a profession and not just a pastime.

At 18, Fernandéz was assigned to the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles of the Carolina League. The young infielder was promoted to the Triple-A Syracuse (New York) Chiefs late the following season. After nearly four full campaigns in the minors, he made his major-league debut with the Blue Jays in a game against the Detroit Tigers at Exhibition Stadium in Toronto on September 2, 1983. Manager Bobby Cox sent Fernández in as a pinch-runner for Cliff Johnson in the eighth inning of a tie game. The rookie advanced to a second a wild pitch, to third on a single by Ernie Whitt, and then scored on another wild pitch by Aurelio Lopez. The Jays went on to lose the game in extra innings.

Toronto management was grooming the rookie as a replacement at short for Alfredo Griffin, a fellow Dominican and a stellar fielder himself who would be traded to Oakland after the 1984 season.

The seven-year-old Blue Jays franchise enjoyed its first winning season in 1983. The new shortstop would be a key figure as the team became a contender through the decade with starters Dave Stieb and Jimmy Key, reliever Tom Henke, catcher Ernie Whitt, and an outfield of Lloyd Moseby, Jesse Barfield, and George Bell, yet another superb Dominican to be imported to Canada from Hispaniola. The lineup made the postseason in 1985 (losing the American League Championship Series to the Kansas City Royals in seven games) and 1989 (losing the ALCS to the Oakland A’s in five games). The infamous Blue Jays’ swoon of 1987 during which they lost the final seven games of the season to be passed in the standings by the Detroit Tigers was explained in part by injuries to Whitt and, especially, Fernández, who suffered a fractured olecranon bone at the tip of the elbow of his throwing arm when Bill Madlock of the Tigers took him out in a slide at second base on September 24.

In 1986 Fernández recorded 213 hits, the first Blue Jay to beat the 200-hit marker. That season he played in the first of five career All-Star Games (four with Toronto, one with the San Diego Padres) and won his first of the four consecutive Gold Gloves. “He makes the spectacular commonplace,” said teammate Garth Iorg.2 In 1989 he committed just six errors in 741 chances for a .992 fielding average.

After the 1990 season, during which he hit a league-leading 17 triples, Fernández was part of a blockbuster trade when he was dispatched with slugging first baseman Fred “Crime Dog” McGriff to San Diego for Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter.

Fernández played two seasons for the Padres before being traded to the New York Mets. After just 48 games, he was traded to the Blue Jays, who by then were defending world champions. When they repeated by defeating the Philadelphia Phillies in six games in the World Series, the returned shortstop played a key role, banging out seven hits (six singles and a double) in 21 at-bats. He knocked in nine runs in the Series, just one short of Ted Kluszewski’s standard for a six-game Series.

As a free agent, Fernandéz signed with the Cincinnati Reds for 1994, before joining the Yankees the following season. For the Yankees, he played in 108 games and drove in 45 runs, hitting for a .245 batting average with a .322 on-base percentage. He missed the 1996 season as he recovered from a fractured right elbow incurred diving for a groundball in spring training. Fernandéz later signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians, returning to the postseason in 1997. Once again he was superb at the plate, touching Florida Marlins pitchers for 8 hits in 17 at-bats. The shortstop’s contribution to World Series lore came in the bottom of the 11th inning. With a runner on first and one out, Craig Counsellhit a potential inning-ending groundball to Fernández at second base. As the fielder moved to his left to field the ball, he raised his glove just enough to graze the three-hopper, which rolled slowly into right field. On NBC, Bob Costas shouted: “Fernández has it go through him!”3 The runner, Bobby Bonilla, got to third base, only to later be thrown out at the plate by Fernández on a fielder’s choice on Devon White’s grounder. The Marlins went on to win the World Series on Édgar Rentería’s liner up the middle, which pitcher Charles Nagy nearly snagged.

Fernández, a free agent, once again returned to the Blue Jays for two seasons at second and, mostly, third base. The infielder spent the 2000 season in Japan with the Seibu Lions before joining the Milwaukee Brewers at the start of the 2001 season. He was released after 28 games and the Blue Jays yet again picked him up and he saw action in 48 games before retiring as a player.

In 17 seasons, the infielder batted .288 with 2,276 hits, including 92 triples and 94 home runs. In 11 World Series games, he hit .395 with 13 runs batted in. He holds several Blue Jays club records (as of 2019), including hits (1,583), triples (72), and games played (1,450). Fernández was added to the Level of Excellence display at the Rogers Centre in Toronto on September 23, 2001. In 2007 he was inducted into the Pabellón de la Fama de Deporte Dominicana (Dominican Sports Hall of Fame) in Santo Domingo. The following year, he was named to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame at St. Marys, Ontario.

Over the years, Fernández’s dedication to a stretching regimen and a willingness to try all manner of exercise gizmos earned him the locker-room nickname of Mr. Gadget.

The former player spent three years, from 2012 to 2014, as a special assistant to Texas Rangers general manager Jon Daniels.

Fernández became an ordained Pentecostal minister in 2003. Raised in a churchgoing household, he professed to be born again at a clubhouse chapel service at Fenway Park in 1984. “They think because I take things easy, I don’t care about baseball anymore,” he said a year after his revelation. “They take it all wrong. I am a better player because I am playing now for the glorification of God.”4

Fernández and his wife, Clara, as of 2019 operated the Tony Fernandez Foundation, a charitable organization to help underprivileged youth in his homeland. The nonprofit foundation has offices in Canada, the United States, and the Dominican Republic. The foundation has as its goal an ambitious plan to build a stadium, schools, a convention center, an orphanage, gymnasium, trade school, teen dorms, hotel, and a restaurant on a 500-acre spread outside San Pedro.

The couple’s first of five children, Joel, was born July 18, 1985. He was followed by Jonathan, Abraham, Andres, and Jasmine. The first two boys and the first daughter were given names beginning with the letter J in homage to the Jays.

Late in 2017, Fernández announced on Twitter, using the handle @TonyCabezaFdez, which incorporates his childhood nickname, that he had been hospitalized after being diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease. He was released in time for Christmas.

Two years later, his health took a perilous turn. Diagnosed with pneumonia as well as kidney failure, he was put in an induced coma. He died on February 15, 2020, after suffering a stroke in a hospital in Weston, Florida.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the following:

Bjarkman, Peter C. Toronto Blue Jays (London: Bison Books, 1990).

Blair, Jeff. Full Count: Four Decades of Blue Jays Baseball (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2013).

Kurlansky, Mark. The Eastern Stars: How Baseball Changed the Dominican Town of San Pedro de Macoris (New York: Riverhead Books, 2010).

Prats, Frank. “Estadios de Béisbol Dominocanos,” Bajotecho, November 2008.

Turner, Dan. “Jays’ Pennant Dance Has Latin Beat,” Ottawa Citizen, September 27, 1985.

Notes

1 Joe Sexton, “From Poverty to Pushcart to Pros,” New York Times, December 6, 1992.

2 Jim Prime, Tales from the Blue Jays Dugout (New York: Sports Publishing, 2014).

3 Major League Baseball, “1997 WS Gm7: Fernandez Makes Error on Grounder,” YouTube.com, October 2, 2013. youtube.com/watch?v=EpswMjFRZ-M.

4 Wayne Parrish, “Fernandez Gives the Credit to God for Improved Play,” Toronto Star, June 24, 1985.

Full Name

Octavio Antonio Fernandez Castro

Born

June 30, 1962 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

Died

February 16, 2020 at Weston, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.