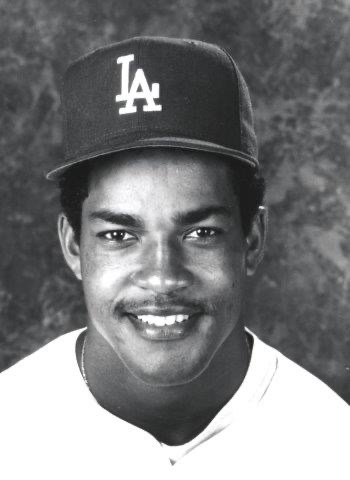

Raúl Mondesí

Raúl Ramón Mondesí possessed a wide array of skills making him a sought-after player early in his career despite a questionable temperament. A powerful arm in right field, he struck fear in baserunners. The might of his swing pushed runners home and balls over the fence. Most surprising given his 5-foot-11 and roughly 220-pound physique, he was an agile and daring baserunner and basestealer. His natural talents and ardent work ethic made him a threat in all phases of the game, yet his disposition and periodic inability to work with managers led to a career that fell far short of the expectations early in his career.

Raúl Ramón Mondesí possessed a wide array of skills making him a sought-after player early in his career despite a questionable temperament. A powerful arm in right field, he struck fear in baserunners. The might of his swing pushed runners home and balls over the fence. Most surprising given his 5-foot-11 and roughly 220-pound physique, he was an agile and daring baserunner and basestealer. His natural talents and ardent work ethic made him a threat in all phases of the game, yet his disposition and periodic inability to work with managers led to a career that fell far short of the expectations early in his career.

Born in San Cristobal, Dominican Republic, on March 12, 1971, Raúl and his five siblings were raised by his mother after his father, Ramon, died when Raul was very young. His mother, Martina, worked at a laundry and managed to support the family.1 Mondesí first found his way to professional baseball in 1988 at age 16. The young talent tried out for the Oakland Athletics at their Dominican facility; however, the team passed on him, declaring him too small for the majors.2 Instead, Pablo Guerrero and Ralph Avila, scouts for the Dodgers, discovered Mondesí when a neighbor arranged an invite the next year to the Dodgers’ development camp. Avila heard Mondesí before seeing him; the sound of the ball striking Mondesí’s bat immediately caught his attention. After watching the work out, Avila ordered his people to sign Mondesí right away. With his signature and a $4,000 signing bonus, Mondesí became part of the Dodgers organization. Despite his natural talent, the future star’s experience with baseball was from the streets of his barrio and makeshift equipment. The Dodgers organization placed him in their Dominican summer league for two years to develop his skills and baseball knowledge.3

In 1990 the Dodgers organization assigned Mondesí to the Great Falls Dodgers in the rookie Pioneer League. In 44 games, he had 53 hits with 31 RBIs, 30 stolen bases, and a slugging percentage of .543. Mondesí clearly had developed the abilities Avila found lacking in 1987. The next year Mondesí found himself with the Class-A Bakersfield Dodgers, but his skills quickly pushed him up to the Double-A San Antonio Missions and then the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes for the last two games of the season. He ended his first full year in the minor leagues with a .277 batting average and 39 RBIs. His 1991 stats, however, also revealed a recurring problem for Mondesí: pitch selectivity. He struck out 69 times with only 13 walks.

During Mondesí’s 1992 season with the Albuquerque Dukes, he exhibited another element that characterized his career: fits of emotional outburst. Toward the end of the 1992 season, the Dodgers promoted Mondesí’s teammate Tom Goodwin to the majors. Mondesí, with marginally better stats, believed the Dodgers owed him the promotion. The Dukes left for a road trip soon after, and an angry Mondesí purposely missed the team plane. Normally this kind of stunt resulted in a fine; however, the Dodgers decided a demotion would be more instructive. Mondesí was sent back down to Double-A San Antonio for the last 18 games of the season.4

With the beginning of the 1993 season, Mondesí was back with the Albuquerque Dukes. Through 110 games, he hit .280 with 65 RBIs. Then in July, the Dodgers called Mondesí up to the majors. As he adjusted to the big leagues, his batting average actually rose, to .291 in the 42 games left in the season. After the season, Mondesí went home to the Dominican Republic to play for the Tigres del Licey club during the winter. The Tigres won the Caribbean World Series and Mondesí batted .450 during the Series.5

With the start of the 1994 season, there was significant anticipation about Mondesí’s performance. Papers predicted that he could win Rookie of the Year, an award his new teammate Mike Piazza won the year before.6 The only question for the Dodgers was whether Mondesí or Cory Snyder would man right field. Despite Snyder’s veteran status, observers cited Mondesí’s speed and powerful bat and predicted that he would easily earn the spot.7 He did.

Mondesí spent most of the 1994 season in right field, With 16 assists, he quickly earned a reputation for turning doubles into singles and making runners who challenged his arm regret it. By April, coaches were already mentioning Mondesí and Roberto Clemente in the same breath. With almost seven weeks of the season canceled by the players strike, Mondesí ended with a .306 batting average, 56 RBIs, and 16 stolen bases. His only downside, according to Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda was his terrible walk-to-strikeout ratio.8 Yet, his strong hitting and impressive fielding made him the unanimous choice among voters for National League Rookie of the Year.

Mondesí’s 1995 season was just as productive as his rookie year with increases in home run, RBIs, and stolen bases. His performance in right field continued to be a serious threat in the league, leading to a Gold Glove Award at the close of the season. Mondesí’s 1995 stats are all the more impressive because he played the last part of the season with torn cartilage in his knee. The Dodgers made it to the postseason, Mondesí went 2-for-9 as they were swept by the Reds in three games. At the end of October, Mondesí had arthroscopic surgery on his knee to fix the cartilage issue.9 By January, he was back playing in the Dominican League.10

In the spring of 1996, Mondesí reported his knee felt great and signed a two-year contract with the Dodgers for $3.65 million. Despite the celebratory feel of the beginning of his third season with the Dodgers, Mondesí’s batting average took a serious dive over a two-week period that included 24 consecutive at-bats without a hit. On May 5 he was hitting only .192.11 The reason for the slump was trademark Mondesí: He was swinging at anything and everything. Lasorda and Mondesí agreed on the diagnosis and the treatment, intensive work with the hitting coach. At the end of April, he hit two singles and a three-run home run, and drove in five runs in a game. By June, he had worked his average back up to .258. Despite the rough start to the season, Mondesí finished the season batting .297, with 88 RBIs and the Dodgers’ record for most extra-base hits, 71. The Dodgers just barely missed the postseason.

Mondesí spent three more seasons with the Dodgers. For a time, he became more selective in his pitching and toed the line with new manager Bill Russell. In addition to his superstitious routines of glove placement between innings, Mondesí also began wearing his pants rolled up to his socks after a successful experiment led to six hits in two days.12 The 1997 season proved to be his best offensive year, as he batted.310 with a good deal more walks and fewer strikeouts. The Dodgers re-signed him in 1998 to a four-year deal with a guaranteed $36 million.13 The 1998 season, however, brought repeated injuries, an unwanted move to center field, and a drunk-driving arrest.14

In 1999 Mondesí was back in right field but his placement in the lineup became a new point of contention. The team moved him from third to fifth in the batting order, and he became more vocal about his frustration. Even with 99 RBIs by the end of the season, his average had slipped to the lowest point of his career so far, .253. During a July 29 game, Mondesí sat in the bullpen while the team batted. In May left fielder Gary Sheffield publicly defended Mondesí, but in August he demanded a trade unless the team dealt with Mondesí’s disruptions.15 After being benched for showing up late to an August 10 game, Mondesí engaged in a “profanity laced tirade” against manager Davey Johnson and general manager Kevin Malone and declared that he “no longer considers himself a member of the Dodgers.” Even after an apology, the team had little choice but to trade him.16

By November, Mondesí was off to Toronto along with pitcher Pedro Borbon in exchange for right fielder Shawn Green and a minor-league second baseman.17 With a new home and a new, four-year, $45 million contract, Mondesí seemed to be back in old form during the 2000 season. Impressed with his fielding and daring speed around the bases, Toronto also found him to be a positive influence in the clubhouse.18 Despite his rediscovered attitude and work ethic, his lack of ball selectivity returned, resulting in a noticeable decline in his productivity in the third spot of the batting order.19

Mondesí started the 2001 season by becoming the first Toronto Blue Jays player to steal home. In a game against the New York Yankees on April 17, he edged his way down the third-base line, and with pitcher Randy Keisler’s windup, he sprinted home on a high and outside pitch. Catcher Jorge Posada did not come close to tagging him out.20 The rest of the season, though, offered little more for Mondesí. His batting average slipped to .252 in a serious late-season slump. Needing to reduce their payroll and begin a rebuilding process, the Blue Jays looked for a buyer for Mondesí’s expensive contract.21

Mondesí returned to Toronto for the 2002 season even as the team was still shopping the 31-year-old right fielder. The Yankees took Mondesí in July, giving up a minor-league pitcher and paying the rest of his 2002 salary and $7 million of the $13 million owed him for 2003.22 Immediately, Yankees manager Joe Torre made it known to the public and Mondesí that he expected discipline and a team-first attitude.23 Again, his comments to the papers toed the line, and he appeared to be fitting into the system. He hit his first home run for the Yankees three days after the trade, but in August he had his first run-in with Torre’s expectations. After a home run against the Tampa Bay Rays, Mondesí jogged to first base with bat in hand and then casually flipped it in front of the Rays dugout. Torre was not amused and reprimanded the hitter. 24

After the 2002 season, the Pirates offered a trade for Mondesí but owner George Steinbrenner refused, saying the Pirates wanted New York to pay too much of Mondesí’s salary. The team asked him to lose weight over the summer, and Jorge Posada worked with him on his grip to improve his hitting.25 Observers and the team, however, were still concerned about his lack of discipline at the plate. Their concerns were warranted. On July 11 Mondesí had just one hit in his last 24 at-bats. Torre benched him.26 Later in July, Torre pinch-hit for the struggling hitter. Infuriated, Mondesí left the field, showered, and went home. The next day Torre expelled him for the stunt. Mondesí, through his agent, demanded that the Yankees trade him. Within a few days, on July 29, he was off to the Arizona Diamondbacks for the rest of 2003.27

After the 2003 season, Mondesí entered free agency; however, his declining production and reputation as difficult left him with few options. The Pirates, who had tried to purchase his contract the previous winter, signed him in February of 2004 for $1.15 million, just 12 percent of his 2003 career-high salary.28 The 2004 season continued to bring problems for Mondesí. Former major leaguer Mario Guerrero sued Mondesí and several other players claiming that they owed him a portion of their salary for connecting them with major-league teams. According to Guerrero, Mondesí had promised him 1 percent of his salary.

A court in the Dominican Republic, found for Mario Guerrero and ordered Mondesi to pay $1 million. Out of concern for his family and to appeal the court decision, Mondesí asked for a leave of absence from the Pirates. He had put up stellar numbers for the Pirates before the court case became an issue. The distraction pushed him into a serious slump, so the team agreed to some time off.29 However, Mondesí did not return for a three-game series in San Diego as promised. He felt unable to return and the team could not afford an absentee player, so the Pirates terminated his contract.30

A week later Mondesí signed a contract with the first-place Anaheim Angels. After only eight games, a tear to his right quadricep ended his time with the team. While on the disabled list, Mondesí missed multiple rehabilitation appointments. The Angels terminated his contract at the end of July.31

Mondesí returned to baseball in 2005 slimmer and without the distractions of lawsuits and issues at home. The Atlanta Braves and Mondesí agreed to a $1 million contract that included performance bonuses if he reclaimed his old power at the plate. The comeback lasted only two months. The team designated him for assignment on June 1, his playing limited because of a sore knee. Mondesí’s baseball career was over.32

Throughout his career, Mondesí demonstrated a profound dedication to the Dominican Republic and especially to San Cristobal. After Hurricane Georges struck the island in 1998, Mondesí arranged for the first humanitarian aid to reach his hometown.33 Between his commitment to his home and the Dominican Republic’s fondness for celebrity political candidates, Mondesí’s entry into Dominican politics was hardly surprising. First as a member of the legislature and then as mayor of San Cristobal from 2010 to 2016, Mondesí spoke often of helping the poor of his city and country. Another expected cause for the new politician was supporting and investing in athletic facilities for youngsters. In 2014 he spearheaded a major renovation of Radhames Park, which included facilities for various sports.34

Despite some successes as mayor, continual complaints of mismanagement plagued Mondesí’s term. After he left office in 2016, the new mayor ordered an audit of the city’s finances. Shortly after, Mondesí was convicted of various crimes relating to mismanagement of city funds and corruption. The court sentenced him to eight years in prison and a fine of about $1.25 million. Mondesí’s defenders claimed he was a victim of corrupt courts and a political system seeking to discredit him.35

Mondesí ended his career with a lifetime average of .273 with his best year coming in 1997, when he hit .310 with a slugging percentage of .541. His on-base percentage always lagged due to the rarity of his walks. Only in his last year with Los Angeles and his second year with Toronto did Mondesí exhibit selectivity in his pitches, walking 71 and 73 times respectively. Every other year, his strikeouts tempered his ability to hit and steal bases. His value in right field is seen more in the impressions of fellow players and writers than in the stats. Sportswriters attributed his falling assist numbers to batters’ fear of his arm and choosing not to challenge him.

Mondesí’s two sons also entered professional baseball. Raul Mondesí Jr. played for a few years in the minors. Adalberto Mondesí began his career in 2012 and rose through the Kansas City Royals organization. He made his debut with the Royals during Game Three of the 2015 World Series against the New York Mets, striking out in his only at-bat. He had played with the Royals from 2016 – 2022.

For Mondesi’s teammates and managers, his slugging and amazing fielding were the product of a serious work ethic, natural talent, and a passion for the game. However, that same passion ensured a serious amount of discord between Mondesí and his teams when he hit a slump. His inability to control his worst instincts led to numerous moves and poor relations with those meant to support him, likely erasing some of the greatness Ralph Avila saw in the summer of 1988.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also made use of Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Johnette Howard, “The Next Clemente?” Sports Illustrated, May 29, 1995: 38.

2 “Playing Hardball,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1997: 38.

3 Johnette Howard, “The Next Clemente?”

4 Howard.

5 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1994: 23.

6 Steve Dilbeck, “Taking Care,” San Bernardino County Sun, April 3, 1994: C4.

7 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1994: 26.

8 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1994: 23.

9 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1995: 19.

10 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1996: 42.

11 Gordon Verrell, “Los Angeles Dodgers,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1996: 27.

12 Steve Springer, “Club’s Pitch,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1997: 25.

13 “Inside Dish,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1998: 53.

14 “Mondesí Back in the Lineup After DUI,” Daily Herald (Chicago), June 15, 1998: 2.

15 Jason Reid, “Getting Mondesí Stirred Up,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1999: 32; Jason Reid, “Positively Negative,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1999: 72.

16 Reid.

17 “Mondesí Traded for Blue Jays’ Green,” Paris (Texas) News, November 9, 1999: 10A.

18 Tom Maloney, “Toronto,” The Sporting News, September 18, 2000: 62.

19 Tom Maloney, “Toronto,” The Sporting News, June 5, 2000: 41.

20 Tom Maloney, “Toronto,” The Sporting News, April 30, 2001: 19.

21 Tom Maloney, “A.L. East,” The Sporting News, December 17, 2001: 18.

22 Jack Curry, “Yanks Acquire Mondesí in Bid to Boost Offense,” New York Times, July 2, 2002: D1.

23 Liz Robbins, “Mondesí Is Forced to Follow New Rules,” New York Times, July 3, 2002: D3.

24 Ken Davidoff, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, August 5, 2002: 23.

25 Tyler Kepner, “Fit and Feisty, Mondesí Predicts Big Year Ahead,” New York Times, February 22, 2003: D3; Charles Nobles, “Mondesí Ready to Shift Hands, Not Teams,” New York Times, March 14, 2003: D4.

26 Tyler Kepner, “Told to Take a Seat, Mondesí Is Down and Up,” New York Times, July 11, 2003: D3.

27 Bill Finley, “Yankees Criticize Mondesí’s Early Exit,” New York Times, July 31, 2003: D3.

28 “Majors,” Gettysburg Times, February 24, 2004: A1.

29 Jeffrey Cohan, “Mondesí Still Stuck in Courtroom Mess,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 16, 2004: A1.

30 Alan Robinson, “Pirates Cut Ties with Mondesí,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, May 20, 2004: 17.

31 “Baseball Buzz,” Toronto Star, July 31, 2004: C5.

32 “End of the Line for Braves’ Mondesí,” Toronto Star, June 1, 2005: C8.

33 Roberto Valenzuela, “Mondesí no sabe defenderse de una injusticia,” Diario Digital RD, October 2, 2017. diariodigital.com.do/2017/10/02/mondesi-no-sabe-defenderse-una-injusticia.html.

34 “Inician trabajos de remodelacion del Parque Radhames,” Diario Digital RD, August 5, 2014. diariodigital.com.do/2014/08/05/inician-trabajos-de-remodelacion-del-parque-radhames.html.

35 Roberto Valenzuela,“Mondesí no sabe defenderse de una injusticia,” Diario Digital RD, October 2, 2017. diariodigital.com.do/2017/10/02/mondesi-no-sabe-defenderse-una-injusticia.html.

Full Name

Raul Ramon Mondesi Avelino

Born

March 12, 1971 at San Cristobal, San Cristobal (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.