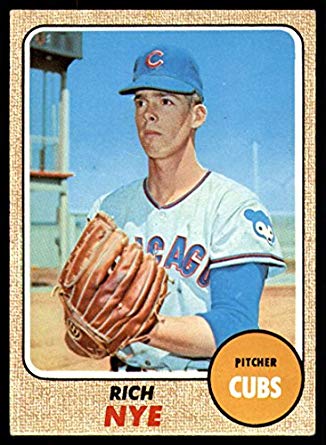

Rich Nye

Like many of us, Rich Nye followed a winding path before finding his true professional calling. What sets Nye apart from you and me, though, is that his journey included pitching duels with Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson; road trips with Hall-of-Fame teammates Ernie Banks and Ferguson Jenkins; and head-to-head showdowns with the likes of Willie Mays and Henry Aaron. A lanky 6’ 5” left-hander who burst on the scene with 13 wins for the Cubs in 1967 and pitched for five seasons before retiring with arm trouble, the multi-talented Nye also dabbled as a civil engineer and spent years as a commodities trader before finally settling into his dream career as a veterinarian and founder of the nation’s first clinic for exotic animals.

Like many of us, Rich Nye followed a winding path before finding his true professional calling. What sets Nye apart from you and me, though, is that his journey included pitching duels with Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson; road trips with Hall-of-Fame teammates Ernie Banks and Ferguson Jenkins; and head-to-head showdowns with the likes of Willie Mays and Henry Aaron. A lanky 6’ 5” left-hander who burst on the scene with 13 wins for the Cubs in 1967 and pitched for five seasons before retiring with arm trouble, the multi-talented Nye also dabbled as a civil engineer and spent years as a commodities trader before finally settling into his dream career as a veterinarian and founder of the nation’s first clinic for exotic animals.

Richard Nye was born Richard Raymond Kruschke on August 4, 1944, in Oakland, California, to Omer and Lorraine (Sandy) Kruschke before the family changed its surname to Nye a couple of years later. He spent his early years in the East Bay city of Martinez (Joe DiMaggio’s birthplace) before moving in the mid-1950s to nearby Walnut Creek, where Omer owned a shoe store. Nye was the middle child, with an older brother, Robert, now a retired history professor, and a younger sister Lorrie, who became a high ranking official with the United States Geologic Survey. Nye started playing baseball at age nine when Robert recruited him to pitch for Robert’s Little League team. “My grandfather said I was a natural,” said Nye. “When you get positive reinforcement like that, you just want to keep going.”1

At Las Lomas High School, Nye was initially an outfielder, but asked to pitch in his sophomore year. He started for the varsity squad as a junior, but missed his senior season due to a basketball injury.

It was Nye’s academic promise, not his athletic ability, that gained him entrance to the University of California, Berkeley on an engineering scholarship. He made the freshman baseball team as a walk-on and pitched well, including a seven-inning perfect game in which he struck out 14.2 Cal rewarded Nye with an athletic scholarship and a varsity slot the following year (1964), and he responded with a 5-4 record and 2.14 ERA.

By this time, the Free Speech Movement was in full swing on the Berkeley campus, but Nye was focused on his studies and on baseball. “I was an observer, not a participant,” he said. “I was so busy with the things I was doing. . . I stood in the shadows. I wasn’t going to get arrested. It was a crazy time to be on campus.”3 Nye pledged the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity; two of his frat brothers were future major league pitchers Dave Dowling and Larry Colton. (Colton’s memoir, Goat Brothers, offers an interesting baseball-tinged snapshot of those turbulent times at Berkeley.)4 Other teammates included outfielder (and future Super Bowl-winning quarterback) Craig Morton; and slugger Mike Epstein.

In 1965, despite a team batting average of .226, Cal contended for the California Intercollegiate Baseball Association championship on the strength of its outstanding pitching.5 Nye was 7-7 with a 2.36 ERA to complement staff ace Andy Messersmith, who went 8-2, 1.63. After the season ended, Nye pitched in an amateur summer league for the Humboldt Crabs in far northern California; the team played in a national tournament in Wichita where he excelled and generated interest from pro scouts. That was the year of the first amateur draft, and Nye was selected by the Houston Astros in the 56th round. “I think I went as low as I did because word had gotten out that I was focused on school. It definitely didn’t make sense to leave school at that point.”6

Nye had another fine season in 1966, going 6-4 with a 1.68 ERA as the third starter behind Messersmith and Bill Frost. Nye was the last of the three selected in the June draft, going in the 14th round to the Chicago Cubs. “They offered me a $5000 bonus, $500 a month, and incentives if I moved up in the system. I thought I couldn’t possibly make that much in my summer job; my dad agreed that it was a good idea to sign, so I did.”7

The Cubs also felt that they’d done well. “He’s one of the best-looking lefties in the area, and lefties are scarce in the Cubs organization,” said Ray Perry, the scout who signed him. “I personally feel very fortunate to get him.”8

Nye reported first to the Cubs’ Caldwell, Idaho, farm club in the Pioneer Rookie League, but was soon re-assigned to the Lodi Crushers of the California League. He was dominant there, including a 17-strikeout performance against the Fresno Giants.9 When the California League season ended in early September, Nye had a record of 5-3, with a 2.87 ERA and 95 strikeouts in 69 innings. Not bad for his first year of professional baseball.

Little did Nye know that his season was not yet finished. A couple days after the California League campaign ended, he got a call telling him he’d been promoted all the way from Single-A to the big leagues: he would join the Cubs during their upcoming series with the Giants at Candlestick Park. “It was amazing,” remembered Nye. “I walk in and I go ‘Wait, there’s Willie Mays!’”10

Nye got into his first action on September 16, starting the second game of a doubleheader against St. Louis and Al Jackson. He held the dangerous Cardinals lineup scoreless through seven innings before tiring and yielding a two-out, three-run homer to Mike Shannon in the eighth in a 4-0 defeat. Nye’s only other start came on September 28; he went seven innings against the Mets and allowed only one run, though the Cubs again failed to score for him and he was tagged with his second loss. Still, when the season ended a few days later, Nye’s 0-2 record was mitigated by his 2.12 ERA, and both he and the Cubs were optimistic about his prospects.

Nye’s first 1967 start was on April 30 in Houston, and he held the Astros to four hits and one run as he went the distance in a 4-1 Cubs victory, his first in the major leagues. He won again a week later against St. Louis, out-dueling Bob Gibson in what would be the first of his five wins that year against future Hall-of-Fame hurlers. By mid-May, Nye had solidified his roster spot and was in the mix for a regular starting role. “With Ken Holtzman going into the Army right away, I have a chance to become our regular fourth starter,” he said. “The Cubs have given me a wonderful opportunity.”11

Manager Leo Durocher gushed about Nye’s talent and make-up. “He’s just great, that kid. He has everything a pitcher needs to stay in the majors. He’s smart. We just wish we had more like him.”12

After a couple losses, Nye rattled off wins in his next five decisions, including a 3-2 victory over Don Drysdale and the Dodgers, and a complete game five-hit, one-run effort against the Mets. Nye’s hot streak was a key component of the Cubs’ best stretch in years. When he beat the Reds, 6-3, on July 1 (not only earning the win, but also scoring the go-ahead run in the 7th after lashing a double) , the Cubs moved within a half-game of the first-place Cardinals, having won 16 of their last 18. The crowd of 31,833 was ecstatic. “I’ve been in baseball a long time and it’s hard to remember a crowd cheering like they did today,” said Pee Wee Reese, who was at Wrigley as a commentator for the nationally televised contest.13 As George Langford of the Chicago Tribune noted wryly, Cubs fans had been waiting a long time for something to cheer about. “Vocal chords that have rested for 20 years can make quite a racket.”14

Nye lost his next two starts, part of a seven-game Cub losing streak that dropped the club 3½ games behind the leaders before Nye stopped the streak with a 2-1 decision over Don Sutton and the Dodgers on July 13 to run his record to 8-5. The Cubs then won 9 of 11 to briefly take over first place in late July. Sadly for the Cub faithful, at that point the Cardinals asserted themselves, beating Chicago eight times in ten meetings during a three-week period. Three of the losses were charged to Nye, the last on August 15 when he took a 2-0 lead into the sixth but gave up five runs in an eventual 6-4 loss that dropped the Cubbies into 4th place, 11 games behind the eventual World Champions.

Nye pitched well again the rest of the way, winning four of his last five decisions, including a victory over the Giants at Candlestick Park in which he struck out a career-high ten batters. He finished with a 13-10 record for a Cubs team that won 87 games, their highest win total since 1945.

Nye’s outstanding rookie campaign earned him a spot on the Topps All-Star Rookie Team and the Chicago Rookie of the Year Award from the local chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.15 Between awards banquets, he returned to Berkeley to work on his Masters in Civil Engineering.16

The surprise success of the Cubs in 1967 spawned high expectations in Chicago for 1968. “We’re coming into this season with a spirited aggressive young club,” said Durocher prior to the start of spring training. “We now have the nucleus to go all the way.” 17

While the offense featuring Banks, Ron Santo, and Billy Williams was seen as the team’s strength, pitching coach Joe Becker was confident that the Cubs’ hurlers would hold up their end of the bargain. Not only would Holtzman be available for the full season to complement staff ace Jenkins, but Becker was also certain that both Nye and Joe Niekro would improve upon their rookie campaigns. “I do not anticipate a letdown . . . I want to go on record as declaring they will be better than they were last year,” said Becker. 18

By the end of spring training, Becker had little reason to alter his thinking—both Nye and Niekro sported ERAs under 2.00.19 Nye was named the starter for the Cubs’ home opener against St. Louis, but he lasted only 2 1/3 innings before he was literally knocked out of the game by a line drive off the bat of Curt Flood that left his pitching arm too bruised to continue. Though he didn’t miss any time, Nye’s fortunes failed to improve, as he lost each of his next four starts before finally earning his first win with a complete game, three-run effort against the Mets in mid-May. In his next start, Nye beat the Dodgers, 1-0, out-dueling Don Sutton while allowing just six hits in his first (and what would turn out to be his only) complete game shutout in the big leagues.

Nye and the Cubs hoped that his gem against the Dodgers would be a turning point, but he continued to struggle. By the middle of July his record was 4-11, his ERA in “the Year of the Pitcher” an unsightly 4.20. At that point, Nye was moved to the bullpen. “The papers said that both Joe Niekro and I were going through the Sophomore Jinx,” said Nye. “It was hard: Leo Durocher didn’t have as much confidence in me as he did the previous year. I didn’t feel Leo communicated very well with pitchers: I don’t think he understood us very well.”20

Over the final two months of the campaign, Nye was used sparingly, appearing in only nine games: five out of the bullpen and four spot starts). He performed better in his new role, going 3-1 with a save and lowering his final ERA to 3.80.

Still, it had been a difficult season, and when Nye had an opportunity to play winter ball in Venezuela, he took it, hoping to rediscover the formula that had worked so well in 1967. The trip was also a honeymoon of sorts, as he was accompanied by his new bride, the former Linda Selander, a model and art student he had met in Chicago the previous year. He pitched well, going 10-6 and winning two playoff games for the eventual league champions La Guaira. “He looked very good,” said his Venezuelan (and Chicago) teammate Adolfo Phillips. “He looked like he was confident. He threw harder and had a better curve.”21

Nye agreed. “I think the trip helped me,” he said. “It was necessary for me because I had to regain my confidence and I did.” 22 But despite his mental state, the Cubs’ coaching staff used him sparingly in spring training. “They encouraged me to take it easy since I’d been pitching all winter. It was a different feeling, and hard to get in a groove. I pitched a bit and worked on a slider, but I didn’t get out there much.”23

Nye made the 1969 club, but lost the fourth starter spot he had occupied most of the previous two seasons. It was the first year of divisional play; the Cubs got off to a tremendous start and led the Eastern Division for most of the way, but did so without getting much out of their bullpen. “He (Nye) was young and had good stuff, and young pitchers with good stuff need to work, but he didn’t,” said his 1969 bullpen mate Ted Abernathy in a 1997 interview. “We should have won it all that summer, but Leo didn’t use us. Hank Aguirre, Don Nottebart, Rich, myself, we needed to work to stay sharp, and we didn’t do anything but stare at each other.24

The inactivity, including a one-month stretch in May and June when he pitched only one inning, was hard on Nye. “People have asked me why I didn’t push harder with Leo in 1969 … My arm was healthy. I was young. Why didn’t I go to Leo and tell him I could try to give the team 200 innings? The answer is Leo himself. Leo was unapproachable. He had his tough-guy image to maintain, and you just didn’t question him. And part of it had to do with me as well. It wasn’t in my nature to go to a manager that way.”25

With Durocher leaning hard on his “big three” starters (Jenkins, Bill Hands, and Holtzman), the Cubs led by nine games as late as mid-August. But the heavy workload caught up with the starting staff; they began to struggle, and the Miracle Mets roared past them to win the division by a comfortable eight-game margin on their way to the World Championship. Nye finished with a 3-5 record and 5.09 E.R.A. He decided to play winter ball in Venezuela again, hoping to regain his sharpness with more work. While he was there, the Cubs announced they had traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals for outfielder Charlie “Boots” Day. Unfortunately, they didn’t bother to tell Nye: he found out a few days later from his mother-in-law.26 “It was like being thrown out of the family,” his wife told a reporter.27

By the time he returned to the States, Nye was philosophical about the trade. “In this game, you can’t live on your past accomplishments, or, as the saying goes, yesterday’s home run won’t win today’s game,” Nye told Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. One benefit he saw in the trade, he noted wryly, was that he’d no longer have to face the Cardinals, against whom he had a lifetime 1-7 record. “Now I just hope that I can pitch better for the Cardinals than I did against them . . . that (Julian) Javier must have hit .700 against me.”28

But Nye struggled in spring training; after he gave up five runs in a third of an inning in a late-March contest against the Phillies, manager Red Schoendienst was blunt. “When we get past our first six men, we don’t have a very potent pitching staff and we’re in trouble.”29 Nye threw only eight regular season innings for the Cards before they sold him to the Montreal Expos in mid-May.

The Expos sent him to their AAA affiliate in Buffalo, where misfortune struck. “I tried to throw too hard too soon down there and felt something go in my shoulder. It was probably my rotator cuff,” said Nye. “They gave me a cortisone shot and called me up. Back then nobody really knew how to manage an injury like that; you would ice your arm after pitching and get cortisone shots.”30

Despite the injury, Nye’s first three starts went well. He had two complete game wins in which he gave up only one earned run, along with a no-decision in which he allowed two earned runs in 7 2/3 innings. His effectiveness soon diminished, however. He did manage one more win—his last in the big leagues—on August 1 against the Dodgers, despite giving up five earned runs. As fate would have it, his last appearance in the majors came a few days later against the Cubs. In one inning of relief work, he gave up five hits, a walk, and two earned runs. The last out he recorded was on a grounder off the bat of former teammate and future Hall-of-Famer Ron Santo.

In 1971, Nye reported to spring training but was sent down to AAA, where he spent the entire season. Ineffective and injured, and now a father of a baby boy (Eric), he realized that baseball had ceased to be enjoyable. “I said to myself: ‘I have a degree, why am I doing this?”31

In 1972, the 27-year-old Nye was unsigned but was in the Phoenix area when major league players went on strike. “I contacted the Cubs to see if there was any interest. They had me throw and I thought I pitched pretty well, but then the manager Jim Marshall said they weren’t signing anyone right then. At that point I called the Major League offices to confirm how much service time I had; they told me four years and three days (four years was the minimum to qualify for a pension). I turned to my wife and said, ‘That’s it, I’m done.’”32

Although by now Nye had a Master’s degree in engineering, he had acquired enough hands-on experience during the off-seasons to know that his heart wasn’t in it. “Taking soil samples 90 feet down in Chicago in winter. . . I wasn’t passionate about that,” he said.33 What he was passionate about, he realized, was animals.

“I always loved a variety of animals growing up, and when I played ball, in all the cities we were in, I looked to see if they had any zoos in the area,” he said. “I’d ask, ‘Where can I go look at animals?’ I felt I had a connection with them somehow.”34

So after retiring from baseball, Nye applied for and was granted admission to veterinary school at the University of Illinois, where he was able to work closely with Dr. Ted Lafeber, a world-renowned expert in avian medicine. “He offered me a job after I graduated in 1976, so I started seeing birds and just fell in love with it. It was such a fascinating field.”35

In addition to his work with birds, Nye, by now a father of two after his youngest son Andrew’s birth in 1974, made house calls to treat dogs and cats as he tried to build up his practice. Around that time, his brother-in-law, who worked at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange as a commodities broker, offered Nye a position assisting him. “I would be in the “live hog pit” selling pork futures from about 7:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.,” said Nye.36 It was tiring work but also exhilarating at times. “As a pitcher, there’s an adrenaline rush when you’re getting ready to play—standing in the pit could be like that, too.”37 After the Mercantile Exchange closed each day, Nye would continue working on building up his veterinary practice, in part by visiting pet stores that sold birds.

In the mid-1980s, at the suggestion of his friend Dr. Susan Brown, who shared an interest in veterinary medicine for exotic animals, Nye decided to join her in founding the aptly named Midwest Bird and Exotic Animal Hospital in Westchester, Illinois, the first of its kind in the country. Around that time, Nye and his wife Linda separated. Nye and Susan later became romantic partners as well as business partners, and ended up dating for 13 years before marrying.

Nye kept working at the Mercantile Exchange for several years as a currency trader after opening the practice. The money he earned there allowed him to put any veterinary revenues back into the business as it continued to grow. In 1993 he decided to step away from trading. “There was no intrinsic value in what I was doing, it was all about money. It makes you very desensitized.”38

With only one career to focus on for one of the few times in his life, Nye became a nationally-recognized expert in avian medicine. He has lectured widely, authored chapters on the subject in textbooks, and served as the President of the Association of Avian Veterinarians. His business also continued to grow and thrive, expanding to five full-time veterinarians by the time he and Susan sold the practice in 2004. In 2007, Nye became affiliated with another exotic animal practice in the Chicago area, where despite his claim to be retired, he continues at age 75 to practice part-time while also pursuing his latest passion, woodturning/wood art.39

After years of toiling on a pitcher’s mound, on construction job sites, and at the Mercantile Exchange, it’s clear that Rich Nye figured out the color of his parachute.

Last revised: November 14, 2019

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Chris Rainey and Norman Macht, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also utilized Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

2 “Cal Freshman Nye Tosses Perfect Game,” Oakland Tribune, March 20, 1963: 42.

3 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

4 Larry Colton, Goat Brothers: (New York, Doubleday, 1993).

5 “Hill Corps Kept Cal in Flag Race,” Oakland Tribune, May 20, 1965: 42.

6 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018

7 Interview

8 “Cubs Sign Cal Hurler Rich Nye,” Oakland Tribune, June 13, 1966: 45.

9 “Lodi Crushers Hand Fresno Working Over,” Reno Gazette-Journal, August 10, 1966: 23.

10 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

11 Pat Frizzell, “Eastbay Pitcher Rich Nye: From Cal to Cubs in Year,” Oakland Tribune, May 16, 1967: 51.

12 Ibid.

13 George Langford, “Response of Cubs Fans Raises the Goose Bumps,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1967: 53.

14 Langford

15 Edward Prell, “Baseball Notables at Dinner Tonight,” Chicago Tribune, January 14, 1968: 82.

16 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

17 Edward Prell, “Cubs Have What it Takes to Hit the Jackpot,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1968: 73.

18 Edward Prell, “Cubs Pin Flag Bid on Pitchers,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1968: 55.

19 Richard Dozer, “Cubs N.L. Opener in Cincinnati Postponed,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1968: 57.

20 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

21 George Langford, “Confidence in Self is Back, Says Rich Nye,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1969: 60.

22 Langford

23 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

24 Jim Mueller, “For Rich Nye, Life After the Cubs is Really for the Birds,” Chicago Tribune, March 9, 1997: 384.

25 “The Summer of ’69,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 2015: 101.

26 Joan Zyda, “His Life Happy Out of Baseball,” Akron Beacon Journal, May 21, 1976: B-5.

27 Zyda

28 Bob Broeg, “New Redbird Nye Knows Score, Won’t Put Rap on Durocher,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 1, 1970: 45.

29 Neal Russo, “Hughes Afraid of Big, Bad Wolf,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 1, 1970: 72.

30 Author interview with Rich Nye, November 11, 2018.

31 Interview

32 Interview

33 Jim McFarlin, “Rich Nye: From Cubs Pitcher to Exotic Vet Pioneer,” University of Illinois Alumni News, February 22, 2017.

34 McFarlin

35 McFarlin

36 Author interview with Rich Nye, August 21, 2019.

37 Interview

38 Interview

39 Nyewoodturning.tumblr.com

Full Name

Richard Raymond Nye

Born

August 4, 1944 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.