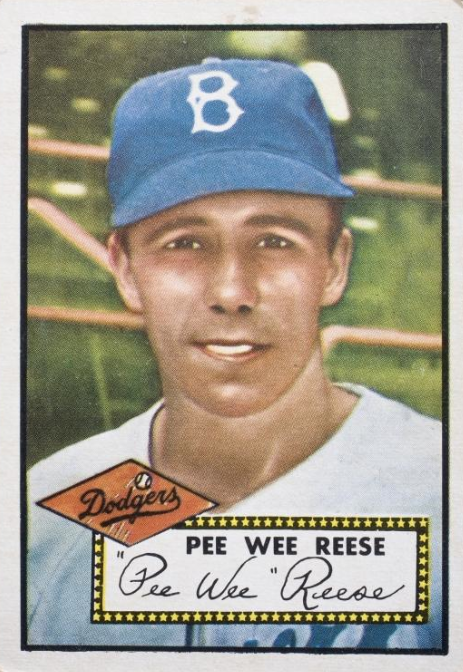

Pee Wee Reese

Outside MCU Park in Coney Island, there stands a statue of two baseball players. Both are famed Brooklyn Dodgers. Both are Hall of Famers whose legends transcend batting averages and fielding percentages. One is a white Kentuckian. The other is an African-American from California. They are Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson.

Outside MCU Park in Coney Island, there stands a statue of two baseball players. Both are famed Brooklyn Dodgers. Both are Hall of Famers whose legends transcend batting averages and fielding percentages. One is a white Kentuckian. The other is an African-American from California. They are Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson.

The statue depicts a simple act that was extremely brave for its time: 1947, when America was a separate but unequal society and Robinson became the first of his race to play major-league ball in the 20th century. That May, according to legend, the Dodgers were battling the Reds at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, located about a 90-minute drive from Louisville, Reese’s hometown. The crowd was mocking Jackie during infield practice. The opposing players were razzing him. The scene was growing uglier by the second. In a display of support for his teammate, Pee Wee calmly strode from his shortstop position toward Jackie on the right side of the infield and placed his left arm around the black man’s shoulder: an act that is commemorated by the statue.

This demonstration quieted the fans, and the Reds. It was a crucial moment in Robinson’s evolution from outsider to big leaguer. Just as significantly, it defined the character and career of Pee Wee Reese, the quietly forceful captain of the postwar Brooklyn Dodgers.

Harold Henry Reese was born on July 23, 1918, on a farm located between Ekron and Brandenburg in Meade County, Kentucky, about forty-five miles south of Louisville. The Reese family, headed by Harold’s father, Carl Marion Reese, and his mother, Emma Allen Reese, relocated to Louisville when he was seven years old. The youngster earned his nickname not for his diminutive size—he was five feet nine inches and weighed 140 pounds when he signed his first professional contract at the age of twenty, and added one inch and twenty pounds when fully grown. Instead, he was called Pee Wee because of his predilection for playing marbles. As a pre-teenager, he was runner-up in a Louisville Courier-Journal pee-wee marbles competition.

Pee Wee also loved playing baseball—even though his size prevented him from earning a starting job on the Louisville Manual High School team; he admitted he got into only five games during his senior year. In fact, in 1956, The Sporting News ran a 1934 photo of “a Louisville amateur team” that featured Pee Wee’s older brother, Carl, Jr., in uniform. Fifteen-year-old Pee Wee was in the shot, but was dressed in street clothes. He was the team’s batboy.1

As a boy, Reese helped support his family by delivering newspapers and selling box lunches. After graduating from high school in 1936, he held several jobs, the most prominent of which was as an apprentice cable splicer for the telephone company. “I was really tiny in high school,” he recalled years later. “Climbing up and down those poles really built me up.”2 In the meantime, he kept playing ball, primarily for a team representing the New Covenant Presbyterian Church.

Reese’s club won the 1937 Louisville city championship. He was its sparkplug and, at season’s end, the Louisville Colonels of the American Association signed him to a professional contract. He was given a $200 signing bonus, and his starting salary was $150 a month. In 1938, Reese hit a solid .277 and stole twenty-three of twenty-four bases. His fielding percentage was only .939, but he impressed with his steady play and maturity, and it was while playing in Louisville that Reese earned a second nickname: The Little Colonel.

At the time, the Colonels had no major-league affiliation. But in September Tom Yawkey, owner of the Boston Red Sox, was part of a group that purchased the team for $195,000. Reportedly, the deal was completed so that the Red Sox would be guaranteed the rights to Reese. According to The Sporting News, “the deal was guarded with such secrecy that some officials of the Louisville club actually did not know that [the Red Sox] were interested in the Colonels.”3

Pee Wee might have become the Red Sox shortstop if not for the presence of Joe Cronin, the team’s player-manager. Cronin, who was to keep playing for another six seasons, showed no interest in relinquishing the shortstop position. So midway through the 1939 campaign, the Red Sox sold Reese to the Brooklyn Dodgers for $35,000 and four players to be named later, each of whom was valued at $10,000. Upon consummating the deal, it was decided that Reese would finish the season in Louisville and come to the Dodgers training camp the following spring.

A news item, published in The Sporting News on July 27, dubbed Pee Wee (who was referred to throughout as “Pewee”) a “sensational 19-year-old shortstop.”4

At the time, he was hitting .278 and leading the American Association with twenty-five stolen bases; he finished the campaign with thirty-five steals in thirty-six attempts. Larry MacPhail, Brooklyn’s general manager, called him “the most instinctive base-runner I’ve ever seen.”5

Ted McGrew, a Dodgers scout, chimed in, “What amazes me is how much he’s learned in so short a time.”6 Donie Bush, the Colonels’ manager and one of the team’s co-owners, told The Sporting News that he “thinks Reese is the best-fielding shortstop he’s seen in his thirty-one years in the game.”7 The paper added, “Bill Meyer, manager of the Kansas City Blues, and Babe Ganzel, St. Paul pilot, when informed of Reese’s sale … called him the best infield prospect in the league. Reese also was described as “probably the most popular player ever to wear a Louisville uniform.”8

At the time, Pee Wee was anxious to play in Boston and was disconsolate upon learning of the sale, which was consummated while he was in Kansas City, playing for the American Association All-Stars. When a newspaperman told him about the deal, he reportedly responded, “Oh, not Brooklyn!”9 Reese’s reasoning was that the Dodgers then had a well-earned reputation for on-field ineptitude. Their record the previous season was 69-80, good for seventh place. In 1937 they were a sixth-place club with an even worse record: 62-91. “I was crushed,” Reese recalled years later. But he readily admitted that the deal “turned out to be the greatest break of my life.”10

Before making it into an in-season box score, Reese was hyped for stardom. An ad featured in The Sporting News on March 21, 1940, was headlined “On his way to the top! With LOUISVILLE SLUGGERS.” It featured an image of Pee Wee, with a “B” on his cap, swinging a bat. The copy read, “Harold ‘Pee-Wee’ Reese with the Louisville Colonels in 1939, now at the Brooklyn Training Camp, stands a good chance of carving a permanent spot for himself with the Dodgers. Reese is one of the younger users of Louisville Sluggers.”11

It was in spring training in Clearwater, Florida, that player-manager Leo Durocher, the Dodgers’ incumbent shortstop, hit grounder after grounder to the baby-faced rookie. After one such session, an exhausted Durocher quipped, “He’ll do. I’ll be the bench manager.”12 Leo also mentored the young infielder. “Leo could be tough,” Reese recalled. “He fined me $50 one day for being out of position on a relay, but he taught me a lot, including to be myself, not try to be Leo Durocher.”13

Pee Wee made his Dodgers debut on April 23, 1940. The Boston Bees (as the Braves were then called) were in Brooklyn, and Reese went 1-for-3 with a walk and a run batted in. He also made a throwing error.

On May 26 he hit his first big-league home run, a game-winner against the Phillies in the tenth inning that broke a 1–1 deadlock. Then on July 3, with the score tied 3–3 against the Giants in the ninth inning, Reese, as reported in The Sporting News, “rammed one of Hy Vandenberg’s fast ones against the foul pole of the upper left tier [of the Polo Grounds] to clear the sacks and sink the Giants. . . .”14 On August 4, in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader against the Cubs, Reese drove home two runs with a sixth-inning single. Then in the bottom of the ninth inning, he homered off Claude Passeau to tie the score at 6–6. Dolph Camilli’s 11th-inning four-bagger won the game.

More significant than his hitting, Reese immediately distinguished himself as a slick fielder and first-class base runner. He was particularly adept at turning his back to home plate and scooting into left field to nab a popup, and dashing from his shortstop position to second base to scoop up a grounder headed toward center field and fire the ball to first for the out. However, due to injury, his rookie season proved to be tough going. On June 1, in a game against the Cubs at Wrigley Field, hurler Jake Mooty tossed Reese a high inside pitch. Pee Wee was temporarily blinded by the white-shirted fans in the center-field bleachers, and he froze. Mooty’s pitch hit Reese in the head. He was carted off to the Illinois Masonic Hospital, where he remained for two and a half weeks. Upon his return to the lineup, on June 21, Reese promptly singled, doubled, and tripled.

Then a broken heel bone, which he sustained while sliding into second base in Brooklyn on August 15, ended his season. These injuries kept Pee Wee out of all but eighty-four games, in which he hit a respectable .272. He began the 1941 campaign with a brace on his ankle, yet he still played in 152 games. His average, however, dropped to .229. Reese felt he contributed little to Brooklyn’s first National League pennant-winner since 1920.

In 1942, during spring training, Dorothy “Dottie” Walton, Pee Wee’s hometown sweetheart, headed south to visit the ballplayer in the company of Patricia Hurst, the girlfriend of fellow Dodger Pete Reiser. On March 29 Dottie and Pee Wee were married in the First Presbyterian Church in Daytona Beach. Later that day, Pat and Pete also wed. The Reeses eventually had two children, Barbara and Mark.

After hitting .255 that season, Reese enlisted in the United States Navy and spent most of the next three years in the Pacific Theater with the Seabees, the Navy’s Construction Battalion. While returning from Guam on board ship, a fellow Seabee informed him he had just heard that the Dodgers had signed a black ballplayer. Plus, he was a shortstop. Would this player upstage Pee Wee, and take his job? At first, Reese was disbelieving. After all, blacks could not play beside whites. They would weaken under the pressure of everyday competition, let alone a pennant race. Pee Wee had been taught that, explicitly and implicitly, his entire life. But of course, the Dodgers had indeed signed Jackie Robinson.

Reese returned to the Dodgers for the 1946 season, during which he played in 152 games and hit a solid .284. The following year, he also hit .284 and walked 104 times, leading the National League. But his notoriety that season transcended these or any other stats.

At the outset of the 1947 season, the Dodgers promoted Robinson to the majors. Reese was well aware that some teammates and fans, neighbors and friends, and even family members vehemently opposed his playing with an African-American. The shortstop was, after all, a product of a segregated Southern culture, and he had never had a catch with an African-American, never had a close relationship with an African-American, and reportedly never had shaken the hand of one. But he was aware of racism American-style. In his youth, Pee Wee’s father reportedly had pointed out to him a tree with a long branch in Brandenburg that had been used for lynching black men, and implied that such actions were unjust. So a sense of fairness had been instilled in him and he was determined to accept his new teammate, no matter what. When several Brooklyn players began passing around a petition protesting Robinson’s presence on the Dodgers, Pee Wee rebuffed them, declining to sign it.

Decades later, Reese explained his rationale by observing, “If he’s man enough to take my job, I’m not gonna like it, but, dammit, black or white, he deserves it.”15 He added that he often would approach Robinson on the field and chat with him for all to see. It was this expression of solidarity on that one May day in Cincinnati that is best remembered today.

Robinson could not recall what Reese said to him—if he said anything. According to Ralph Branca, their teammate, Reese’s gesture communicated to the players in the opposing dugout, “Hey, he’s my friend. It says Brooklyn on my uniform and Brooklyn on his and I respect him.”16 Years later, he explained his action by telling Roger Kahn “I was just trying to make the world a little bit better. That’s what you’re supposed to do with your life, isn’t it?”17

On one level, this story is apocryphal. Duke Snider, for one, recalled that the incident took place in Boston. According to an account in The Sporting News published in 1956, it first occurred during a 1947 exhibition game in Fort Worth, when “a foghorn-voiced Texas fan ‘got on’ Jackie with the kind of comments that need not be described” and, later on in the season, in Boston, Reese “made almost an identical gesture—the gesture that told the world that Robinson was his teammate.”18 Then in 1984 the very same paper reported that the incident took place in Cincinnati. In a 1952 magazine article and his book Wait Till Next Year, published in 1960, Robinson himself recalled that the incident took place in Boston—in 1948. Carl Erskine claimed to be present when it happened, and he did not become a Dodger until 1948. According to some recollections, Reese made his gesture during infield practice. Others recalled that it occurred during the game, prior to the home team’s at-bat. The 1984 Sporting News account had it taking place in-game, when the Dodgers were in the field, after Jackie had committed an error.

But the essence of the tale is spot-on—and, during that 1947 campaign, Reese and Robinson became friends. Often, while on the road, the duo competed on the tennis court and golf course. As Reese noted, the comradeship “just happened, and Jackie appreciated it. I told him I wasn’t trying to be the great white father. We became very close friends. . . . He was just a fine individual, one of the greatest competitors I’ve ever seen.”19

Their relationship was such that Reese could effectively employ humor to ease a tense situation. On one occasion, when the Dodgers were scheduled to play an exhibition game in Atlanta, Robinson received a letter threatening his life. Reese responded by teasing his teammate. “Don’t come near me,” he kidded Robinson. “I don’t want to get shot.”20

On the field, Robinson spent the 1947 season as the Dodgers’ first baseman. He then was switched to second base, where he and Reese developed into an outstanding double play combination. In 1949 Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ president and general manager, named Reese the team’s captain, telling Pee Wee, “You’re not only the logical choice, you are the only possible choice; the players all respect you.”21 Afterward, Reese’s teammates began referring to him by a third nickname: The Captain. One of his duties was to remain atop the Ebbets Field dugout steps prior to the beginning of each game and wave the starters onto the field.

“He took charge out there,” noted Robinson, “in a way to help all of us—especially the pitchers. When Pee Wee told us where to play or gave some of us the devil, somehow it was easy to take. He just has a way about him of saying the right thing.”22

The following season, there even was talk that Rickey would name Reese player-manager, replacing Burt Shotton. At the time, the team was in transition, with many of Pee Wee’s early teammates having been replaced by those who formed the nucleus of the 1950s Brooklyn clubs. But Rickey felt that Reese, who by then was well-practiced in adjusting the team’s defense and strategizing with the pitcher, was no mere relic of the old guard of Dodgers. He was, instead, most valuable to the team as player and field captain. So Shotton remained manager in 1950. He was replaced by Charlie Dressen in 1951; Walter Alston took over for Dressen three years later. Regarding Reese’s holdover status, Rickey pronounced, “Reese? Last of the old Dodgers? Wouldn’t it be better to say he is the first of the new Dodgers?”23

As the 1950s progressed, a debate raged in New York over which of the city’s teams had the best players. Just as Brooklyn fans favored Duke Snider in center field, while Giants aficionados chose Willie Mays and Yankees rooters preferred Mickey Mantle, there were also endless debates comparing the prowess of Pee Wee versus the talents of Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto. Which one was the slicker fielder? Which one was the superior bunter? Which one was better in the clutch? Which one was the more inspirational team leader? Meanwhile, by 1953, Branch Rickey had left Brooklyn and was running the Pittsburgh Pirates. He attempted to trade for Reese, to captain the punchless Pirates. Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers’ new owner, flatly refused.

What was inarguable, however, was the Dodgers fans’ adoration of their shortstop. He was a special favorite in Brooklyn, with Pee Wee Reese fan clubs sprouting up across the borough. The ballplayer was particularly attentive toward youngsters. Unlike so many other major leaguers, he won a reputation for never brushing them off and for honestly and thoughtfully answering their questions.

On July 22, 1955, just before his thirty-seventh birthday, Pee Wee Reese Night was held at Ebbets Field. It was quite an event. A pregame ceremony took almost one hour to complete, during which Reese was presented with $20,000 worth of gifts, including a new Chevrolet, $3,000 worth of United States Savings Bonds, 200 pounds of food in a freezer, and honorary membership in the Teamsters Union. A hoarse-voiced Pee Wee told the crowd, “When I came to Brooklyn in 1940 I was a scared kid. To tell you the truth, I’m twice as scared right now.”24 After the top half of the fifth inning, two vast birthday cakes were wheeled onto the field. The ballyard’s lights were lowered, and the 33,000 fans on hand lit matches or turned on cigarette lighters and serenaded their shortstop with a hearty “Happy Birthday.”

That season, the Dodgers yet again made it to the World Series. And yet again, they faced the New York Yankees, who had defeated them all five previous times they had battled. Pee Wee had a solid series, scoring five runs and hitting .296. As usual, his contributions transcended what might be culled from a box score. In the bottom of the sixth inning of Game Seven, Billy Martin walked, Gil McDougald bunted safely, and Yogi Berra bashed the ball into the left-field corner. Surely, this would be an extra-base hit, and would net the Yankees a pair of runs. But left-fielder Sandy Amoros snared the ball before it hit the ground. Reese, meanwhile, ran out to short left field to take Amoros’ cutoff throw. He quickly spun around and fired a strike to Gil Hodges to double McDougald off first—and preserve the Dodgers’ shutout.

Appropriately, it was Reese who fielded the final ball hit by a Yankee in Game Seven. The date was October 4, 1955. The time was 3:43 P.M., and the Dodgers were beating the Bronx Bombers, 2-0. Pee Wee’s toss of Elston Howard’s ninth-inning, two-out grounder to Hodges closed out the Series, and the season. Finally, the Brooklyn Dodgers were the world champions.

Reese now was a veteran major leaguer, but he still was a first rate player. In its 1956 season preview, Sports Illustrated listed Reese as the team’s number-one “mainstay.”25 Regrettably, he twisted his back early in spring training, and there was some concern as to how this would impact his season. He ended up playing in 147 games, 136 at shortstop and twelve at third base. While his statistics remained respectable, they collectively were down from previous seasons. But he remained a powerful presence in the Ebbets Field locker room, ensconced in an armchair and smoking a pipe, and he readily mentored his younger teammates, dispensing sage, hard-nosed advice. At one point, Johnny Podres, then in his early twenties, complained that he was losing too many low-scoring games. When, he wondered, will the Dodgers run up the score for him? Reese’s counsel was brief, and pointed: Perhaps, the veteran suggested, the young hurler needed to win some 1-0 games himself. This quieted Podres down. Years later he admitted it was a lesson well-learned.

During each season a number of Dodgers, including Reese and Duke Snider, lived in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn and drove to and from Ebbets Field during home stands. After a game, Snider often wanted to hastily depart the ballyard and head home. “Duke, Duke,” Reese once told him, “if you’re hurryin’ out of the clubhouse, you’re hurryin’ out of baseball.”26

The 1956 season, however, was Reese’s last as a regular. In 1957 he got into only 103 games, with his batting average shrinking to .224. He played shortstop in just twenty-three contests; most of the time, he patrolled third base. Twenty-five-year-old Charlie Neal, then being groomed as Pee Wee’s replacement at short, played the position in 100 games.

In 1958 the Dodgers abandoned Brooklyn for Los Angeles. That season Reese got into only fifty-nine games. His .224 batting average was identical to his 1957 mark. His poor showing paralleled the fortunes of the Dodgers, who finished the year entrenched in seventh place.

Given his team’s new West Coast address, Pee Wee also went Hollywood, becoming one of the first of the Dodgers to accept a movie or television acting role. He appeared as himself in “A Question of Romance,” a TV drama about a young woman torn between her expertise on baseball and her insecure, baseball-hating boyfriend. When it was learned that Reese would be on the show, he was kidded by his teammates, who compared him to everyone from Gregory Peck and Tyrone Power to Frankenstein. “A Question of Romance” aired on November 9, 1958, on CBS-TV’s General Electric Theater.

But clearly, Reese’s career as an active player was winding down. At season’s end, the Dodgers hierarchy allowed him the option of becoming a coach. The Sporting News reported that the Cleveland Indians were interested in him as a player, but he explained, “And as long as I’m in baseball I would like to stay with the Dodgers. I realize there’s no place for me in their youth movement, but maybe I’ll stay on as a coach.”27 On December 18, 1958 Buzzy Bavasi, the Dodgers’ general manager, announced that Reese had retired as a player and accepted a position on manager Walter Alston’s coaching staff. “He could have remained on the active roster of another major-league club but the Dodgers, in rebuilding their team, must make room for another youngster,” Bavasi declared. “That’s baseball.”28

From 1946 through 1956, the final year he was the team’s regular shortstop, Reese’s batting averaged generally was in the .270s or .280s. His highest home run total was sixteen, in 1949. That season, he led all National League shortstops with a .977 fielding percentage and topped the NL with 132 runs scored. His highest RBI total was eighty-four and his highest hit total was 176, both in 1951. In 1952 he topped the senior circuit with thirty stolen bases.

Reese’s lifetime batting average was .269. All told, he appeared in 2,166 games, had 2,170 hits, and is the Dodgers’ all-time leader with 1,338 runs scored and 1,210 walks. He hit .272 in forty-four World Series games. In the 1955 Fall Classic he established a mark for shortstops by taking part in seven double plays in a seven-game series, a record he equaled the following season.

These generally unspectacular statistics obscure Reese’s value to the Dodgers. Even though he hit .300 just once—in 1954 when, at age thirty-six, his average was .309, with a career-best slugging percentage of .455 and second-best on-base percentage of .404—he finished in the top ten in the National League MVP voting on eight occasions. He was a top-notch bunter and hit-and-run man. He made the NL All-Star Team in 1942 and each season from 1946 to 1954. In 1948, 1949, and 1953 he was an All-Star Game starter. In all the years in which Reese was the team’s full-time shortstop, the Dodgers never finished lower than third place.

After spending the 1959 season as a Dodgers coach, Reese seguéd into a new career as a color man on televised baseball broadcasts. First he replaced Buddy Blattner as Dizzy Dean’s partner on CBS-TV’s Game of the Week. He worked at CBS from 1960 to 1965; during his final season there, he and Dean broadcast twenty-one New York Yankees home games on Yankee Baseball Game of the Week and the two were partnered on Sports with Dizzy Dean & Pee Wee Reese, a chat show. Then in 1966, he moved over to NBC, where he was paired with Curt Gowdy. In March 1969 NBC abruptly announced Reese had been fired. It was a mystery to him as to why his contract was not renewed. “Did I talk too much?” he wondered. “Didn’t I talk enough?”29

He added, “I spent three great years with NBC and six with CBS. But it’s going to feel strange to be out of baseball this year. I’ve been in the sport for thirty years.”30 He needn’t have worried. Scant weeks after leaving NBC, Pee Wee was hired to join Ed Kennedy in the Cincinnati Reds broadcast booth, replacing Frank McCormick. He remained with the Reds for two seasons and then finished his career with a lengthy stint in the employ of the Louisville-based Hillerich & Bradsby Company, the maker of Louisville Slugger bats. His jobs included director of the organization’s college and professional baseball workforce and sales representative with major-league ball clubs. He also represented Hillerich & Bradsby at public functions.

In 1984 Reese’s uniform number—which, appropriately, was “1”—was retired by the Dodgers. That same year, the veterans committee elected him to the Baseball Hall of Fame. His Hall of Fame plaque reads: “Shortstop and captain of great Dodger teams of 1940’s and 50’s. Intangible qualities of subtle leadership on and off field. Competitive fire and professional pride complemented dependable glove, reliable base-running and clutch-hitting as significant factors in 7 Dodger pennants. Instrumental in easing acceptance of Jackie Robinson as baseball’s first black performer.”

As he aged, Reese suffered a variety of illnesses. He was afflicted with prostate cancer, which he overcame. Then in March 1997, doctors removed a malignant tumor from his lung, and he underwent radiation treatment. Adding to his woes was a broken hip. By this time he was making few public appearances.

Pee Wee Reese died at his Louisville home two years later, on August 14, 1999. He was eighty-one years old, and had been married to his beloved Dottie for fifty-seven years. He was survived by her, his son and daughter, three grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. The first Saturday after Reese’s death, flags at Dodger Stadium were flown at half-staff. His funeral was held at Louisville’s Southeast Christian Church. There were 2,000 attendees, among them practically all of Reese’s surviving teammates, from Joe Black to Don Zimmer. He was buried in Rest Haven Memorial Cemetery in Louisville.

Speaking at Reese’s funeral, Joe Black, the African-American Dodgers hurler, declared, “Pee Wee helped make my boyhood dream come true to play in the majors, the World Series. When Pee Wee reached out to Jackie, all of us in the Negro League smiled and said it was the first time that a white guy had accepted us. When I finally got up to Brooklyn, I went to Pee Wee and said, ‘Black people love you. When you touched Jackie, you touched all of us.’ With Pee Wee, it was No.1 on his uniform and No. 1 in our hearts.”31

Sources

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press, 2001.

Polner, Murray. Branch Rickey. New York: New American Library, 1982.

Bingham, Walter. “Underlying Pessimism: The Los Angeles Dodgers’ Great Stars are Aging or Absent, and This Team Will Win No Pennant.” Sports Illustrated, March 24, 1958.

Creamer, Robert. “How to Do It Again.” Sports Illustrated, March 19, 1956.

——.“The Curtain Rises.” Sports Illustrated, October 15, 1956.

——. “Twilight of the Bums.” Sports Illustrated, April 1, 1957.

“Brooklyn Dodgers.” Sports Illustrated, September 26, 1955.

“Brooklyn Dodgers.” Sports Illustrated, April 9, 1956.

“Los Angeles Dodgers.” Sports Illustrated, April 14, 1958.

Berkow, Ira.“Reese Helped Change Baseball.” New York Times, March 31, 1997.

——. “Two Men Who Did the Right Thing.” New York Times, November 2, 2005.

Bodley, Hal. “Robinson Drew Praise From Many Corners.” USA Today, April 13, 2007.

Broeg, Bob. “Pee Wee Was No Dodger Midget.” Sporting News, April 23, 1977.

Dudley, Bruce. “Louisville Hails Bush-Red Sox Purchase; Price Under $200,000.” Sporting News, September 15, 1938.

Finch, Frank. “Reese, All-Time Dodger at Short, Hangs Up Glove to Become Coach.” Sporting News, December 24, 1958.

Fitzgerald, Tommy. “Brooklyn in $75,000 Deal for Reese, Who ‘Didn’t Want to Be a Dodger.’ ” Sporting News, July 27, 1939.

Goldstein, Richard. “Pee Wee Reese, 81, Captain of the ‘Boys of Summer,’ Is Dead.” New York Times, August 15, 1999.

Kindred, Dave. “An Artist at Life.” Sporting News, August 30, 1999.

McGowen, Roscoe, “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

——. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 26, 1956.

——. “Robinson’s Gone, But Randy Faces New Brooks Battle.” Sporting News, December 26, 1956.

Miller, Stuart. “Breaking the Truth Barrier.” New York Times, April 14, 2007.

Plaschke, Bill. “No 1 On Your Scorecard…” The Sporting News, August 23, 1999.

Samuelsen, Rube. “Dodgers Leave It Up to Reese! Utility Role or a Coaching Post.” Sporting News, October 29, 1958.

Vecsey, George. “Sports of the Times: Reese Has His Heirs, Even Today.” New York Times, August 17, 1999.

“Ex-Shortstops to Throw Words on NBC Telecasts.” Sporting News, April 23, 1966.

“Five for the Hall: Pee Wee Reese.” Sporting News, August 6, 1984.

“Game Still Tops to Reese After Debut on Video.” Sporting News, November 19, 1958.

“NBC Fires Reese; Koufax Sent to Bullpen.” Sporting News, March 22, 1969.

“On the RADIO AIRLINES.” Sporting News, March 16, 1939.

“Paid Notice: Deaths REESE, PEE WEE.” New York Times, August 18, 1999.

“Pee Wee Dodger Coach? ‘All They Have to Do Is Ask Me.’” Sporting News, November 26, 1958.

“Pee Wee Reese Accepts Job With Bat Company.” Sporting News, July 31, 1971.

“Reese Replaces McCormick on Red Telecasting Team.” Sporting News, April 5, 1969.

“Reese’s Gesture.” New York Times, August 6, 2000.

“The Day Jackie Robinson Was Embraced.” New York Times, April 21, 2007.

“Web Videocasts of Major Games to Open April 16.” Sporting News, March 23, 1960.

Notes

1. “At 15, Batboy for Brother’s Team.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

2. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

3. Dudley, Bruce. “Louisville Hails Bush-Red Sox Purchase; Price Under $200,000.” Sporting News, September 15, 1938.

4. Fitzgerald, Tommy. “Brooklyn in $75,000 Deal for Reese, Who ‘Didn’t Want to Be a Dodger.’” Sporting News, July 27, 1939.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

10. “Five for the Hall: Pee Wee Reese.” Sporting News, August 6, 1984.

11. Display Ad, Sporting News, March 21, 1940.

12. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

13. Broeg, Bob. “Pee Wee Was No Dodger Midget.” Sporting News, April 23, 1977.

14. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 26, 1956.

15. Kahn, Roger. “He Didn’t Speculate in Color.” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1999.

16. Bodley, Hal. “Robinson Drew Praise From Many Corners.” USA Today, April 13, 2007.

17. Kahn, Roger. Into My Own: The Remarkable People and Events That Shaped a Life. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006.

18. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

19. Bodley, Hal. “Robinson Drew Praise From Many Corners.” USA Today, April 13, 2007.

20. “Five for the Hall: Pee Wee Reese.” Sporting News, August 6, 1984.

21. McGowen, Roscoe. “PEE WEE .. Pride of Flatbush.” Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Wait Till Next Year: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

25. “Brooklyn Dodgers.” Sports Illustrated, April 9, 1956.

26. Vecsey, George. “Sports of the Times: Reese Has His Heirs, Even Today.” New York Times, August 17, 1999.

27. “Game Still Tops to Reese After Debut on Video.” Sporting News, November 19, 1958.

28. Finch, Frank. “Reese, All-Time Dodger at Short, Hangs Up Glove to Become Coach.” Sporting News, December 24, 1958.

29. “NBC Fires Reese; Koufax Sent to Bullpen.” Sporting News, March 22, 1969.

30. Ibid.

31. “Rachel Robinson Recalls How The Late Pee Wee Reese Helped Jackie Robinson Integrate Baseball.” Jet, September 13, 1999.

Full Name

Harold Henry Reese

Born

July 23, 1918 at Ekron, KY (USA)

Died

August 14, 1999 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.