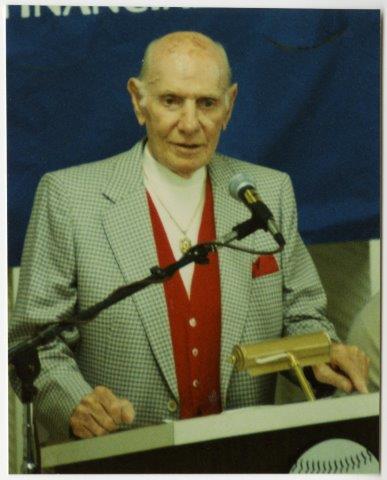

Leo Durocher

From his birth in 1905, in West Springfield, Massachusetts, to his death in 1991, in Palm Springs, California, Leo Durocher witnessed a great deal of social, political, and international change, some of which he helped bring about. Durocher played an important supporting role in the integration of major-league baseball. His frank assessment of African American baseball talent remains a simple, if coarse, endorsement of the American belief in meritocracy. He stood in the third-base coach’s box for one of baseball’s most memorable home runs, Bobby Thomson’s 1951 “Shot Heard ’Round the World” off Ralph Branca. He led the New York Giants to a surprising World Series victory in 1954.

More than a decade later Durocher piloted the Chicago Cubs through 6½ frustrating seasons, always falling short of the postseason. Along the way Durocher kept company with movie stars, entertainers, and an entire retinue of shady underworld characters. He had legal difficulties, four divorces, and fights with fans, jilted women, and angered husbands, fathers, and boyfriends. Through it all he maintained the utmost confidence in his own ability to come out ahead. Then as now, many have seen Durocher’s competitiveness as an excuse for playing dirty.

Durocher found success in both playing and managing, winning World Series titles while playing shortstop for the 1928 Yankees and 1934 Cardinals, and then as the manager of the 1954 Giants. He won National League pennants, but no world championships, with the 1941 Brooklyn Dodgers and the 1951 Giants. Finally, the famous phrase “nice guys finish last,” attributed to him, has achieved recognition throughout American culture.

Leo Ernest Durocher was born on July 27, 1905, to George and Clarinda (Provost) Durocher in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He was the youngest of four sons, but at 5-feet-10 grew to be the tallest. His French-Canadian parents often spoke French at home. George Durocher worked on the railroad, for the Boston & Albany Railroad. Like his older brothers, Leo served Mass at the local Quebecois parish, St. Louis. Durocher said he “went through grammar school and then began at Springfield Technical High School, but he got into a fight with a male mathematics teacher in his second year, was suspended for 30 days and never went back.”1

Durocher also became quite adept at playing pool, and soon frequented the local pool halls to hustle money. His athletic abilities also became evident. While playing several sports, Leo became a local baseball prodigy, playing for the Merrick Athletic Association, in the Catholic Junior League, and in a local industrial league. Company teams offered him increasingly lucrative and easy jobs if he would play for them and not for competing companies.

In 1925, bird-dog scouts Jack O’Hara and Arthur Shean recommended the 19-year-old Durocher to play for the Hartford Senators, where he struggled at the plate but played sparkling defense.2

Leo had previously caught the eye of Yankees chief scout Paul Krichell while playing semipro ball, but Krichell failed to sign the raw talent on the spot, and instead shelled out $7,500 to purchase Durocher’s contract at season’s end in time for a two-game trial that October.3

Durocher broke into professional baseball with Hartford of the Eastern League in 1925 and earned a call-up to the Yankees that season. He got into two games and had one at-bat. Durocher spent the next two seasons in the minor leagues, at Atlanta of the Southern Association (1926) and St. Paul of the American Association (1927). He came back to the Yankees in 1928 and never completely left the major leagues until his retirement in 1973.

Durocher’s time with the Yankees was volcanic. Protected by manager Miller Huggins, he quickly made enemies with his incessant yapping, extravagant living, and antagonizing of Yankees stars like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Ruth nicknamed Durocher the “All-American Out” for his diminutive batting average. Ruth also accused Durocher of stealing his watch, a charge Durocher denied vehemently.

Durocher lost his protective mantle when Huggins died in 1929, and he was waived to the Cincinnati Reds before the 1930 season. In Cincinnati he found his gambling appetite even more easily indulged than in New York. He married Ruby Hartley in 1930 and fathered a child. The marriage quickly fell apart, and the couple divorced in 1934. Durocher omitted this first marriage — and his only biological child — in his 1975 autobiography. Midway through the 1933 season, mired in debt and a dissolving marriage, Durocher was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. He became captain of the famous Gas House Gang, the 1934 Cardinals team that fought with one another as much as with the opposition and won the World Series against Detroit in seven games.

On September 27 Durocher took time to remarry, this time to Grace Dozier, a prominent St. Louis businesswoman and fashion designer who paid off Leo’s substantial debts. After the 1937 season, friction between Leo and the Cardinals’ player-manager, Frankie Frisch, led to a trade to the Brooklyn Dodgers. There Durocher reunited with Larry MacPhail, who had traded him from Cincinnati to Branch Rickey’s Cardinals. After the 1938 season Durocher became the Dodgers’ player-manager.

Leo received his nicknames “The Lip” or “Lippy” during his first full year in the majors, 1928. The roots for these names, and the behavior that spawned them, reached back to his boyhood days in West Springfield. Durocher dutifully idolized Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, the Boston Braves’ diminutive shortstop who hailed from nearby Springfield. Maranville, only 5-feet-5 and weighing 155 pounds, recognized that smaller players needed a mental edge to compensate for their lack of size.

Maranville came to know of the neighborhood’s emerging star. He once told the young Leo, “Never back up,” because “the first backward step a little man takes is the one that’s going to kill him.”4 Maranville obviously meant this advice to apply to fielding the ball, but one might wonder if Leo took Maranville a bit too literally. George Durocher and his other sons exhibited the rock-ribbed but nonetheless quiet stoicism that French-Canadian immigrants were known for in the Northeast. Maranville’s words could also be understood as “don’t back down from a fight,” advice Leo often took to heart.

The tutorials in baseball’s mental game continued as Leo progressed through the minor leagues. Miller Huggins completed Leo’s apprenticeship when he reached New York. During the 1928 season with the Yankees Durocher became a full-blown loudmouth bench jockey. The verbal assaults continued through his managing years. Boyhood friends who visited Durocher for games would note that almost every one of Leo’s sentences included several obscenities. Branch Rickey once remarked of Durocher, when pushed into a corner, “He’s still that kid from West Springfield with a pool cue butt in his hand.”5

From the earliest days of his playing career to the end of his managing days, Durocher loved to yap. Miller Huggins had encouraged the 160-pound youngster to compensate for his weak bat with hustle. Huggins, Leo said, “kept telling me I’d stick around for a long time if I kept my cockiness and my scrappiness and that fierce desire to do anything to win.”6 Durocher willingly obliged his mentor. First as a player then as a manager, he never shied away from verbal combat. As of 2014, Durocher ranked third all-time for the most times ejected from a major-league game as a player or a manager. Strictly as a manager, Durocher ranks fourth.

As a player Durocher also distinguished himself with quick fielding. Throughout his managerial career he often reverted to his boyhood games, playing pepper with players several decades younger than himself. Even when he managed the Cubs in his 60s, Durocher surprised two of his stars, Ernie Banks and Ron Santo, with his ability to keep up with the younger players.

Durocher was certainly not a threat with the bat. He was a career .247 hitter, with just 24 home runs. His highest batting average came in 1936, when he hit .286 for the Cardinals. Overall, though, he performed better the preceding year, hitting .265 in 143 games. That season (1935) included career highs in home runs (8), slugging percentage (.376), and RBIs (78).

Durocher’s already limited productivity tailed off significantly in the 1940s. In 1940 he played in little more than half the games (62) he had the year before, and came to bat only 175 times. In 1939 Durocher came in eighth in the MVP voting, and he was second among shortstops. In 1941, 1943, and 1945, his last three years playing, he appeared in only 26 games total, batting just 67 times. (He managed, but did not play for, the Dodgers in 1942 and 1944.) In 1941 Brooklyn won its first pennant since 1920, but lost the World Series to the Yankees in five games. The next year, the Dodgers won 104 games but lost the pennant to the Cardinals. Brooklyn finished third in 1943, the same year Durocher and Grace Dozier were divorced.

With the players who had been in the military returning in 1946, Leo shifted over to managing full time. It was in that season that he purportedly made his well-known statement “nice guys finish last.” Aimed at the last-place Giants and their manager, Mel Ott, the phrase quickly took on a life of its own, appearing in all sorts of publications, popular and scholarly, ever since.

The groundbreaking 1947 season was noticeable for Durocher’s absence. He had been present during spring training in Havana, Cuba, playing along with Branch Rickey’s orchestration of Jackie Robinson’s promotion to Brooklyn. Throughout the winter Rickey had planted stories that Durocher was “pressuring” him to add Robinson to the Dodgers’ roster. However, just when Rickey was ready to announce that Robinson would in fact start on Opening Day, Durocher’s past threw Rickey and the Dodgers an exploding curveball.

On the very day Robinson was to be introduced, Commissioner Albert B. “Happy” Chandler suspended Durocher from baseball for a year. Chandler claimed that Durocher had once again associated with known gamblers. Prior to a 1947 spring training game in Havana, Durocher noticed two such men sitting with Yankees owner Larry MacPhail. Rickey and Durocher complained to Chandler about double standards. MacPhail responded by decrying the charges as slanderous. Chandler fined both owners and suspended Durocher, a move that astonished Rickey, Durocher, and Brooklyn’s fans.

This latest fiasco concerning Durocher only added to Rickey’s headaches. In January Leo had been in the papers again — this time for his marriage to the actress Laraine Day, whom he had met in 1945. The Utah-born Day was already married to Ray Hendricks, but in January 1947 Day divorced Hendricks in Mexico, then married Durocher the next day in El Paso, Texas. Back in California, Durocher and Day, who still had a year to wait before her California divorce from Hendricks was final, had to plead before a judge so she could avoid conviction for bigamy.

Compounding the scandal’s impact was a boycott of the Dodgers by the local chapter of the Catholic Youth Organization. The director of the Brooklyn CYO, Rev. Vincent Powell, removed CYO support for the Knothole Gang and published a letter in the newspapers on March 1, 1947, charging that Durocher was “undermining the moral training of Brooklyn’s Roman Catholic youth.”7 The CYO contributed both youths and money to the Brooklyn Knothole Gang, the team’s adolescent fan base. Supported by US Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy, the Brooklyn Diocese had presented Rickey with the ultimatum: fire Durocher for his moral turpitude or face a boycott.

Durocher’s suspension solved the boycott issue; nevertheless, with the beginning of the 1947 season a week away, Rickey had no manager for his new team. Eventually he named Burt Shotton as interim manager. Shotton promptly led the team to the National League pennant.

Before he left, Leo did manage to contribute significantly to the Dodgers’ 1947 season. In Havana the Dodgers learned of Rickey’s plan to integrate the team with Robinson. Some players circulated a petition protesting Rickey’s move. As soon as he heard of it, Durocher called a team meeting — at midnight. Surrounded by sleepy and cross players, Durocher flatly told them to “wipe your ass” with the petition. Finally, Leo concluded, many black players shared his own fierce desire to win. They were hungry, and unless the Dodgers and the other white players themselves played harder, they would find themselves replaced. Leo cared about winning, and if that meant starting black players, he had no problem doing so. He went public with his support for Robinson: “I don’t care if he is yellow or black or has stripes like a fucking zebra. I’m his manager and I say he plays.”8

Underneath his coarse language, Leo believed in meritocracy. Those who are most able are the ones who start, regardless of appearance or background. This managerial approach led him to start three African Americans in the 1951 World Series (Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, and Hank Thompson). When he arrived at the Giants’ spring training camp, Hank Thompson recalled Durocher’s introduction: “I’m only going to say one thing about color: You can be green or be pink on this team. If you can play baseball and help this team you’re welcome to play.” Thompson concluded: “And it was true.”9

Throughout the 1947 season, Rickey assured Durocher that he would get his manager’s job back. Shotton’s performance — winning the pennant and pushing the Yankees to seven games in the World Series — made Rickey reconsider his promise, but in the end he kept it. When Leo arrived at spring training in 1948, he did seem changed. Reporters, players, and even Rickey himself noticed that the marriage (and perhaps the suspension) had mellowed him. The old Leo resurfaced briefly when Jackie Robinson reported to camp. Over the winter Robinson had gained significant weight. Durocher reverted to his older hectoring self, badgering Robinson incessantly. Robinson lost the weight and regained his playing form.

Rickey, though, remained unsatisfied. Wishing perhaps for a managerial change himself, Rickey often mused aloud that the team needed shaking up. The season’s start bore out Rickey’s worries as the Dodgers stumbled to a 35-37 record. When Horace Stoneham, owner of the crosstown archrival Giants inquired about Burt Shotton’s availability as a replacement for Mel Ott, Rickey had his chance. With Durocher away in Montreal on a scouting trip, Rickey and Stoneham met. While Rickey did not offer Durocher’s services, he also did not refuse when Stoneham asked for Durocher instead of Shotton.

Thus, the Dodgers’ irascible manager switched in midseason to manage their hated rivals. Fans of both teams were stunned, as was Leo, who did not learn of the managerial trade until he returned. The night the deal was completed, Stoneham visited Laraine Day at the couple’s Manhattan apartment. When she learned the news, she switched off the radio broadcast of that night’s Dodgers game, saying, “Then why am I listening to this?”10

Many of Ott’s players were slow-footed veterans, and Durocher’s aggressive, gambling style did not sit well. He did manage the team to a .519 record (41-38) for the rest of the season. That was only good enough for fifth place in the National League. The next season, 1949, was Durocher’s worst with the Giants; the team finished fifth again, but this time with a 74-83 record. From 1950 through 1955, though, the Giants and Durocher enjoyed five winning seasons, never finishing lower than third. During that span the Giants won two National League pennants and the 1954 World Series. In 1951 they made up a 13-game deficit in August against the Dodgers and forced a three-game playoff for the pennant.

The Giants won the third game, 5-4, on Bobby Thomson’s famed home run. According to author Joshua Prager, Leo did more than just watch; his rudimentary telescope-and-bell system rigged in the Polo Grounds offices 483 feet away from home plate had tipped Durocher, Thomson, and the Giants that Branca was about to throw a fastball. The Giants then lost a hard-fought World Series to the Yankees in six games. In 1954 the Giants swept the heavily favored Cleveland Indians in four games. The next year they finished third, a distant 18½ games behind the Dodgers. After that 1955 season, Stoneham replaced Durocher with Bill Rigney.

Durocher’s stint with the Giants ranked second only to his time with the Dodgers. He managed the Giants for almost 7½ seasons and finished with a .549 winning percentage (637-523). He managed the Dodgers for 8½ seasons and finished only slightly better (738-565). After the Giants replaced him, Durocher pursued his long-desired goal of shifting careers to show business. However, despite his several celebrity friends, most endeavors quickly fell through. His attempt to host a variety show on NBC flopped. Durocher appeared on several television shows, but he made more money doing baseball broadcasts on radio and television. Day divorced him in 1960. Durocher coached for the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1961 to 1964. True to form, he often criticized manager Walter Alston for indecisiveness and tentative leadership.

In 1966 the Chicago Cubs named the 60-year-old Durocher manager. That season Leo suffered through his worst year as a manager, going 59-103. But much like his stint with the Giants, Durocher then led his team through several winning seasons. From 1967 to 1971, the Cubs enjoyed five straight winning seasons.

The club stood at 46-44 when owner Phil Wrigley fired Durocher midway through the 1972 season. Durocher’s time with the Cubs is remembered mostly for what did not happen. For several years the talent-laden club finished below expectations. The 1969 season was the best example. The Cubs led the National League East division for over 100 days, and were 9½ games ahead of the Mets in August. However, the team faltered badly.

The club stood at 46-44 when owner Phil Wrigley fired Durocher midway through the 1972 season. Durocher’s time with the Cubs is remembered mostly for what did not happen. For several years the talent-laden club finished below expectations. The 1969 season was the best example. The Cubs led the National League East division for over 100 days, and were 9½ games ahead of the Mets in August. However, the team faltered badly.

As the season wore on, Durocher misused his pitchers, and his tendency to berate players often backfired. Once again his hard-driving style had begun to wear thin. During two weeks in September, the Cubs fell from five games ahead of the Mets to 4½ games behind them, and eventually finished eight games back. The Cubs finished second again in 1970, albeit without the spectacular meltdown. In 1971 they wound up third. That year the locker room finally boiled over with fights between Durocher and the players. Unlike previous stints with the Dodgers and Giants, Leo never related well with the Cubs’ African American players.

One of his most common managerial tactics was to belittle and enrage players so that they played better. He had picked up this technique from Miller Huggins, and it worked quite well with stars like Jackie Robinson and Sal Maglie. With the Cubs, it backfired. Pitcher Ken Holtzman took offense at Durocher’s repeated use of anti-Semitic remarks. In the years after Curt Flood’s legal challenge to the reserve clause, Durocher’s well-known hostility to union organizing appeared shockingly retrograde. Halfway through the 1972 season, owner Phil Wrigley had enough and replaced Durocher with Whitey Lockman. Leo did not remain idle for long. The Houston Astros made him skipper for the last 31 games of 1972. As before, he wrangled with the team’s established stars, in this case pitcher Larry Dierker. Durocher managed the entire 1973 season, going 82-80, before retiring for good.

Leo moved back to California and waited for the Hall of Fame recognition he felt he was due. He and his fourth wife, Lynne Walker Goldbatt, divorced in 1981, but the couple had already separated years earlier. Durocher had married the Chicago socialite in 1969.

As the years went by, Leo rediscovered his Catholic faith. He served faithfully as an usher at the Saturday evening Mass at his local parish. He also became increasingly bitter over his perceived slight by the Hall of Fame. He died on October 7, 1991, and was buried in Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles. The Hall of Fame recognition finally came in 1994. On Induction Day, Laraine Day accepted the award.

Durocher’s posthumous election to the Baseball Hall of Fame rested exclusively on his managerial career. In 24 seasons, he amassed 2,008 victories and 1,709 losses, a .540 winning percentage. However, Durocher’s effectiveness as a manager exceeded the raw numbers. Throughout his managerial career, he took a tough, scrappy, take-no-prisoners approach to the game. Only at the end of his managerial career did Durocher encounter significant player resistance to his style. When he retired, he seemed a relic from an earlier baseball age.

Sources

Claerbaut, David, Durocher’s Cubs: The Greatest Team That Didn’t Win (Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing, 2000).

Day, Laraine, Day with the Giants, Kyle Crichton, ed. (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1952).

Durocher, Leo, The Dodgers and Me: The Inside Story (Chicago: Ziff-Davis, 1948).

_________, with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975).

Eskenazi, Gerald, The Lip: A Biography of Leo Durocher (New York: Quill, William Morrow & Co., 1993).

Feldmann, Doug, Miracle Collapse: The 1969 Cubs. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon, 2006).

Tygiel, Jules, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. 25th Anniversary Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Hazucha, Andrew, “Leo Durocher’s Last Stand: Anti-Semitism, Racism, and the Cubs Player Rebellion of 1971,” in NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 15 (#1, Fall 2006), 1-12.

Heidenry, John, The Gashouse Gang: How Dizzy Dean, Leo Durocher, Branch Rickey, Pepper Martin, and Their Colorful, Come-From-Behind Ball Club Won the World Series and America’s Heart During the Great Depression (New York: Public Affairs, 2007).

Mandell, David, “The Suspension of Leo Durocher,” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History #27 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2007), 101-04.

Mann, Arthur, Baseball Confidential: Secret History of the War Among Chandler, Durocher, MacPhail, and Rickey (New York: David McKay Company, 1951).

Marlett, Jeffrey, “Durocher as Machiavelli: Good American, Bad Catholic,” in William M. Simons, ed., in The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2007-2008 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 38-50.

_______, “Don’t Give Me No Lip: Durocher’s Management Style and the Integration of Baseball,” in NINE: A Journal of Baseball and American Culture 20:2 (Spring 2012), 43-54. muse.jhu.edu/journals/nine/v020/20.2.marlett.html.

Shaplen, Robert, “The Nine Lives of Leo Durocher,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1955.

Treder, Steve, “A Legacy of What-Ifs: Horace Stoneham and the Integration of the Giants” in NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 10 (#2, 2002), 71-101.

Williams, Peter, “You Can Blame the Media: The Role of the Press in Creating Baseball Villains,” in Alvin L. Hall, ed., in Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1989 (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing and State University of New York College at Oneonta, 1991), 343-60.

Woodward, Stanley. “That Guy Durocher!” Saturday Evening Post, June 3, 1950, 25-27.

Thanks to Rod Nelson for information on the scouting of Leo Durocher.

Notes

1 Robert Shaplen, “Beginning: The Nine Lives of Leo Durocher,” Sports Illustrated, May 23, 1955.

2 Gene Schoor, The Leo Durocher Story (New York: Julian Meissner, 1955) , 30-33, 40.

3 The Sporting News, June 12, 1957, 28.

4 Leo Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, 34.

5 Rickey quoted by Red Smith in William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999), 103.

6 Gerald Eskenazai, The Lip, 248.

7 “Durocher Versus the CYO,” Catholic Digest 11 (June 1947), 96; reprint from The Catholic Mirror (April, 1947).

8 Gerald Eshkenazi, The Lip (New York: Quill, 1993), 248.

9 Leo Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, 46. Gerald Eskenazai, The Lip, 248.

10 Arthur Mann, Baseball Confidential: The Secret History of the War Among Chandler, Durocher, MacPhail, and Rickey (New York: David McKay Co., 1951), 182.

Full Name

Leo Ernest Durocher

Born

July 27, 1905 at West Springfield, MA (USA)

Died

October 7, 1991 at Palm Springs, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.