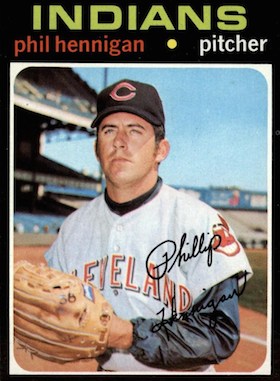

Phil Hennigan

On September 2, 1969, Phil Hennigan made his major-league debut in Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium in relief of Cleveland Indians starter Luis Tiant. Entering the sixth inning with his club trailing 5-1 and the Twins threatening more, Hennigan retired the always-dangerous Rod Carew on one pitch by inducing the future Hall of Fame famer to fly out to centerfield. Afterward Hennigan denied being nervous when facing the AL’s leading hitter, but his awkward denial appeared to belie his true feelings. “’No sir,’ drawled the [native] Texan. ‘I just couldn’t talk.’”1

On September 2, 1969, Phil Hennigan made his major-league debut in Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium in relief of Cleveland Indians starter Luis Tiant. Entering the sixth inning with his club trailing 5-1 and the Twins threatening more, Hennigan retired the always-dangerous Rod Carew on one pitch by inducing the future Hall of Fame famer to fly out to centerfield. Afterward Hennigan denied being nervous when facing the AL’s leading hitter, but his awkward denial appeared to belie his true feelings. “’No sir,’ drawled the [native] Texan. ‘I just couldn’t talk.’”1

The one-pitch out launched a promising career that was cut short by shoulder problems that initially surfaced midway through Hennigan’s rookie season. The injury eventually robbed him of his lightning velocity; near the end of his career the quick-witted right-hander cracked about having “a new pitch. It’s called the ‘nudist ball’ [because i]t’s got nothing on it.”2

In 1973 New York Mets fans dubbed their favorite club’s right-field bullpen “Little Ireland” in honor of the Irish-sounding names of Hennigan and left-handed reliever Tug McGraw. But the name Hennigan was actually a variation of “Henniger,” the surname carried by Phil’s sixth great-grandfather Hans. The latter had arrived in the colony of Pennsylvania from Germany in 1720. The name was changed by Phil’s fourth great-grandfather Michael, a North Carolina native who settled in Bienville Parish in northwest Louisiana around 1850.3 During America’s Civil War Michael’s son Ambrose Hennigan died at Camp Overton in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, most likely from injuries he sustained in the October 21, 1863 Battle of Opelousas. Around the onset of the Great Depression, Ambrose’s grandson William—Phil’s grandfather—moved to Jasper, Texas (130 miles northeast of Houston) where he worked for many years as a public employee despite being legally blind. On April 10, 1946, the future ballplayer—Phillip Winston Hennigan—was born in Jasper to Joseph Polk and Joye Wynell (Phillips) Hennigan.

The small city of Jasper, whose population has never exceeded 8,300, remains large enough to have been home to two major league ballplayers: Hennigan and his 1969 Cleveland Indians third base teammate Max Alvis, who was eight years Hennigan’s senior. Both attended Jasper High School; one of Hennigan’s mound foes was future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan.

In 1963 Hennigan suffered a heartbreaking 2-0 loss to Dumas High School in the state’s conference 4A finals despite pitching seven-innings of no-hit ball. Another no-hitter ended in loss when Hennigan’s older brother Gary—an accomplished ballplayer as well—committed an error at first base that allowed the winning run to score.

Following his high school graduation in 1964 Hennigan travelled 100 miles west to Huntsville, Texas to participate in the very successful baseball program at Sam Houston State University. A year later he teamed with future Mets and Houston Astros infielder Ken Boswell to lead the Sam Houston State Bearkats to their fifth consecutive NAIA College World Series appearance.

Hennigan’s baseball prowess captured the attention of Indians scout Bobby Goff, who had signed Alvis in 1958. A Lone Star native who spent more than two-thirds of his playing and managing career in the low minors in Texas, Goff succeeded in convincing the Indians to select the hard-throwing righty in the fourth round of the January 1966 amateur draft.

Hennigan was assigned to the Reno Silver Sox in the California League (Class-A), where he posted a pedestrian won-lost record of 3-8 with a 4.03 Earned Run Average in 96 innings (30 appearances, 12 starts).

But it was a short-lived stint; in July Hennigan received a call from his mother, who informed him that he had been drafted into the U.S. Army. On August 6, 1966, following a whirlwind courtship, he married Reno native Carolyn Michelle Martini days before his departure.

Hennigan spent one year in combat duty as an artilleryman in the Vietnam War where he earned a medal for bravery. Returning home in January 1968, Hennigan was reassigned to Reno. Moved primarily to relief work under manager Clay Bryant, he made a strong impression with a 3.26 ERA and 76 strikeouts in 80 innings. In 1969 he followed Bryant to the Waterbury (Connecticut) Indians in the Eastern League (Class-AA). Once again working from the bullpen, Hennigan posted a stellar 4-2/1.97 record in his first 18 appearances (64 innings). Waterbury was on its way to a record-setting 93 losses (records from 1950 forward), and a seemingly desperate Bryant inserted Hennigan into the rotation in July. The durable righty finished the season among the circuit leaders in wins (10), innings pitched (154) and strikeouts (114). His win total stood as a Waterbury record for a Cleveland Indians affiliate through 1986.

Hennigan was selected as one of the Indians’ late-season call-ups where he made his successful one-pitch major league debut on September 2, 1969. Far less success followed; his next four appearances included his first major league loss on September 8 against the Boston Red Sox. In that game he blew a one-run lead in the eighth inning, surrendering a two-run single to first baseman George Scott. But one week later the tables turned; Hennigan benefitted from a four-run ninth inning Indians rally against Boston to collect his first win. He yielded just one hit over his last four appearances to finish his month-long debut with a record of 2-1/3.31 in 16⅓ innings.

After the 1969 season Hennigan proceeded to Sarasota, Florida where he drew rave reviews from Indians manager Al Dark while playing in the Florida Instructional League. The 1969 Indians had concluded their worst season in more than a half-century, and Dark was now pinning his hopes on Hennigan and a deep roster of promising youngsters that included pitchers Rich Hand and Ed Farmer, infielder Jack Heidemann and outfielder Frank Baker.

Hennigan’s star continued to rise when, following his brief stint in the FIL, he moved to the Dominican Republic to play winter ball with Aguilas Cibaenas. In January, he combined with Washington Senators righty prospect Jim Miles for a shutout to vault Aguilas into first place. A 2.51 ERA in 65 innings placed Hennigan among the league leaders, and in February he won two of the last three games in a best-of-five series against Estralles Orientales to advance his club to the finals.

Hennigan reported to the Indians 1970 spring camp in Tucson, Arizona where he was even more impressive, surrendering just six hits and no runs over 15⅔ innings in four appearances (one start) through March 25. (Not known for his hitting, Hennigan also helped his own cause in the March 25 game with an eighth inning RBI single that proved to be the deciding run in a 4-3 win over the Oakland Athletics.) “[T]he Indians’ two best pitchers in the Cactus League [are rookies Hennigan and Hand,]” said The Sporting News contributor Russell Schneider. “[T]here’s no doubt those two youngsters will be important factors before the year is over.”4 Wrestling whether to shove Hennigan into the rotation or use him in relief, Dark echoed Schneider’s thoughts: “Hennigan has proved to me he can pitch up here,” the veteran skipper said. “The only question in my mind at this time is how he can be best used.”5 In an apparent coin toss, Dark decided to put Hennigan in the bullpen and Hand in the rotation.

The young hurlers were two of six rookies carried by the “Kiddie Korps” Indians when the club opened the 1970 season at home against the Baltimore Orioles. Following a difficult first few weeks Hennigan settled into a stretch of 4-1/1.56 with 23 strikeouts and a yield of only 22 hits over 12 appearances (34⅔ innings). The fourth win came on June 4 against the Milwaukee Brewers when he relieved lefty Barry Moore after just one batter. In this, the longest appearance of his career, Hennigan scattered seven hits over 6⅔ innings while driving in the decisive run with a third inning, two-out double—the only extra-base hit of his career. On June 13, he earned his first major league start, a short-lived assignment against the Brewers that lasted less than four innings. Except for difficulties against the Detroit Tigers—a club that challenged Hennigan throughout his career—the righty carried a record of 6-2/2.50 in 57⅔ innings through July 17.

But over the next 16 days Hennigan faced just five batters when a mysterious shoulder injury—something he chalked up to experimenting with a screwball—put him on the sidelines. On August 4, one day after his family arrived in Cleveland following a 1,300-mile drive from Houston to watch him play, Hennigan was assigned to the Wichita Aeros in the American Association (Class-AAA) where he could hopefully recover. Recalled in September, Hennigan made five appearances to close the campaign—four strong outings in which he did not surrender an earned run plus another unaccountably disastrous performance against the Tigers. Hennigan finished his rookie season among the club leaders with 42 appearances and a respectable record of 6-3/4.02 in 71⅔ innings. He then spent the winter pitching in Venezuela.

Hennigan’s accident-marred arrival at the Indians camp the following spring seemed to portend an unlucky 1971 season for him. Eighteen of his suits and sport coats were destroyed after his garment bag blew off the limousine transporting him from the Tucson airport to the club’s hotel. The typically strong spring training performer realized only mixed success in Arizona and the club, perhaps suspecting that the shoulder was not fully recovered, offered the 25-year-old to Milwaukee in a package deal for outfielder Tommy Harper. When the Brewers did not bite Hennigan was sent to Wichita alongside Farmer, Heidemann and Frank Baker—the quartet of youngsters that Al Dark had banked on to improve the club’s fortunes a year earlier.

Discouraged by the demotion, Hennigan considered retiring before his wife, who was pregnant with their third child, talked him out of it. The righty returned to the American Association and, surprisingly, began mowing down batters—18 strikeouts and a 1.80 ERA over 15 innings—as his velocity inexplicably returned. “Don’t ask me what happened,” Hennigan said. “Maybe . . . I was trying to pinpoint my pitches too much and in doing so that was taking something off my velocity. I don’t really know . . . as long as my fastball is back, I don’t care where it went.”6

Hennigan’s surge corresponded with the struggles of Indians rookie reliever Chuck Machemehl, and on May 7 the hurlers were swapped out for each other. Four days later Hennigan collected his first win of the season with five innings of two-hit relief against the Athletics while en route to 14 consecutive scoreless innings. Then at the end of the month fate temporarily intervened when Hennigan suffered two straight walk-off losses. The first came on a bases-loaded pass to Chicago White Sox outfielder Jay Johnstone, followed the next day by a ninth-inning home run by Brewers second baseman Ted Kubiak (who had entered the day mired in a 1-for 46 slump). But Hennigan quickly rebounded with a string of 15 strong appearances to finish June with a record of 4-2/1.65 over 32⅔ innings. His restored fastball, and the fear it struck in opposing batters, was aptly illustrated by the comments of Kansas City Royals All-Star outfielder Amos Otis: “As hard as Hennigan throws, I’m not going to make any silly remarks. He might stick one in my ear.”7

But far less success ensued as Hennigan’s shoulder appears to have tired through the second half of the season. On July 5, he surrendered a fourth-inning grand slam to Washington Senators catcher Dick Billings on the way to a 10-run yield in just 3⅔ innings. Except for a brief resurgence in mid-August, Hennigan finished the second half with a record of 0-1/8.26. This included an ugly save against the Red Sox on September 4 in which he coughed up two three-run homers over the last 3⅔ innings in an 11-9 slugfest. Two days later he inherited a one-out, bases- loaded jam against Baltimore. He walked in the go-ahead run before yielding a grand slam to Orioles slugger Boog Powell in an eventual 10-5 Cleveland loss. On September 20 Hennigan’s name was carved into the record books when he became one of a major-league record 18 pitchers used in an extra-inning game against the Senators (a record since broken). In a game begun on September 14 and suspended in the 17th inning, Hennigan’s dubious contribution was to blow a ninth-inning save that allowed the game to go into overtime. It was resumed six days later, and the Senators finally won it in the 20th inning.

Despite a career high 82 innings while also placing among the league leaders in appearances (57), games finished (38) and saves (14), Hennigan finished the 1971 season with a disappointing record of 4-4/4.94—a far cry from his brilliant first half.

Shortly after the season Hennigan’s name surfaced in a proposed trade with the Orioles before Baltimore acquired southpaw reliever Grant Jackson from the Philadelphia Phillies in December. Any further rumors of Hennigan’s departure were quickly extinguished when the Indians new manager Ken Aspromonte announced that the righty would anchor the club’s relief corps alongside sophomore lefty Steve Mingori. Aspromonte’s confidence in Hennigan was based on first-hand experience after having managed the righty in Wichita over portions of the preceding two seasons.

Unfortunately, the skipper did not anticipate Hennigan’s shoulder problems, which continued into the spring of 1972. In March the Indians sent the pitcher to Los Angeles to undergo therapy with Dodgers’ specialist Dr. Robert Kaplan. (One report suggests cortisone shots were part of his therapy as well.) Hennigan was placed on the disabled list and did not make his 1972 debut until May 21. Used sparingly, he yielded only seven earned runs in 16 appearances through 25⅔ innings. The strong rebound drew an accusation from California Angels manager Del Rice that Hennigan was throwing spitballs, a claim the righty dismissed with great humor: “Well, I just hope I have as much success with a pitch I don’t throw as [my teammate] Gaylord Perry does with a pitch he doesn’t throw, either.”8 On July 22 Hennigan made his second—and last—career start. Though it lasted nearly twice the length of his 1970 assignment, the results were approximately the same as he lost 5-3 to the White Sox. Moved back to the bullpen, Hennigan won his next five decisions. Held to just 4⅔ innings after he injured his ankle on September 1 sliding into second base—an injury he appears to have re-aggravated 11 days later—Hennigan finished the season with a career best 2.67 ERA with six saves and a 5-3 mark in 67⅓ innings.

The Indians finished a disappointing fifth, and in a flurry of off-season moves they traded Hennigan to the New York Mets for pitching prospects Bob Rauch and Brent Strom. “I hated to give up Hennigan,” Aspromonte explained. “But you have to give up something good to get something good—and we think Strom and Rauch are very good.”9 Mets manager Yogi Berra called Hennigan to welcome him to the club. Told that the righty was headed out the door to go hunting, and aware his past shoulder problems, Berra advised him to “[s]hoot left-handed.”10

Hennigan’s strong right-handed presence was a welcome addition to a Mets a bullpen anchored by southpaws Tug McGraw and Ray Sadecki. So was his energy; in spring 1973 his new teammates dubbed him “Frisky” for his nervous habit of constant movement while in the bullpen—a label that gained further credence when they first witnessed his career-long habit of sprinting to the mound each time he was called.

On April 11 Hennigan made his National League debut in New York’s Shea Stadium in relief of McGraw. Entering the ninth inning against the St. Louis Cardinals, protecting a one run lead with two outs and two runners on base, Hennigan induced pinch-hitter Bernie Carbo to fly out to center to capture his first save of the season. The next day, in a classic pitching duel between future Hall of Fame righties Bob Gibson and Tom Seaver, Hennigan collected his second save after working 1⅓ innings to preserve a 2-1 win.

A player who quickly made friends among his teammates, Hennigan was also subject to the pranks played by the members of a major-league roster. As related by The Sporting News contributor Dick Young, on an early season road trip Hennigan “fell asleep on the Mets’ plane listening to loud rock music through oversized earphones. Tug McGraw turned up the volume full blast, and nothing happened. ‘Try turning it off,’ said Tom Seaver. Tug did, and Hennigan jumped up as if jabbed.”11 In June he drew the ire of the commissioner’s office when, in a moment of complete frankness, Hennigan told reporters he’d be willing to groove a pitch to Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron during the Hall of Famer’s historic pursuit of Babe Ruth’s career home run title. “Everyone is in this game for money,” Hennigan confessed. “If it’s me, I’ll tell him what’s coming. It will be a half-speed fast ball down the middle. It will be like batting practice. I’d be a fool not to do it.”12 He was far from the only pitcher willing to be immortalized thusly—McGraw and All-Star hurlers Andy Messersmith and Larry Dierker were among a sizeable roster of willing hurlers, each of whom was similarly chastised.

But the early success Hennigan realized with the Mets soon morphed into disappointment. On June 5 he entered the 10th inning in relief of McGraw and surrendered a walk-off three-run homer to future Hall of Fame catcher Johnny Bench. A month later, in what was one of the most humiliating defeats in Mets’ history, Hennigan surrendered six runs and nine hits in two innings in New York’s 19-8 loss to the Montreal Expos. On July 7, in what proved to be his last appearance in the major leagues, Hennigan yielded three runs to the first four batters he faced in an eventual 9-8 loss to the Braves. The outing lifted his ERA above six and resulted in his demotion to the Tidewater (Virginia) Tides in the International League. His velocity seemed to be shot (a career low 4.1 strikeouts per nine innings) as he concluded the season at Tidewater with a miserable 6.32 ERA in 37 innings (seven starts in eight appearances).

During the offseason Hennigan rested in hopes of returning to the Mets with a restored arm. The strategy failed when, following a disappointing 1974 spring training, he was reassigned to Tidewater. After seven relief appearances Hennigan retired, just 75 days shy of qualifying for the players’ pension. “It’s a hard decision,” he admitted. “I’ve been in baseball since 1966 and some say it’s foolish for me to throw it all away. But I don’t look at it that way at all.”13

Hennigan returned to Texas where he launched a 40-year career as a peace officer. In 1984 he moved to Center, Texas (60 miles north of Jasper) where he was eventually promoted to sergeant with the local police department.

Hennigan and his wife had three sons. In 1993 the youngest child, Jeffrey Scott, died from a rare kidney disease. Hennigan’s marriage dissolved in divorce and he eventually married Center native Lynda K. Russell.

Hennigan remained an avid fan of the game he had left years before and enjoyed watching baseball with his surviving sons, Joseph Phillip and Steven Bryan, and his three grandsons. On June 11, 2016 he was elated when his grandson Jonathan Hennigan was selected by the Philadelphia Phillies in the 21st round of the MLB amateur draft. Six days later, and just two months after his 70th birthday, Hennigan died of lung cancer in Center, Texas. (He had contracted the disease in early 2015 and outlived the doctors’ projections by about a year.) On June 20 he was buried at Adams Cemetery in nearby Shelbyville, Texas with military honors under the direction of the U.S. Army Honor Guards.14

Hennigan concluded a five-year major league career with a pedestrian won-lost record of 17-14 and an ERA of 4.26 in 280⅔ innings. He appeared in 176 games, 100 of which he finished. So much more appeared in store for the flame-throwing righty before shoulder problems afflicted him in his rookie season. Like so many strong-armed young pitchers in the history of major league baseball, his was the story of a promising career cut short by an arm injury, and huge potential only partially realized.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee, and Carolyn M. Hennigan and Connie Hennigan Hatton, the ballplayers first wife and sister respectively, for their valuable assistance. Further thanks are extended to Joe DeSantis for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 “Dark Puts $$ Where Heart Is—Half-Million in Tribe,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1969: 23.

2 “Joe Falls column,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1972: 8.

3 Though Pro Football Hall of Fame wide receiver Charley Hennigan was born in the same sparsely populated parish in 1935, the author was unable to find a familial link to Phil Hennigan.

4 “Three Winter Deals Give Tribe Spring Tonic,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1970: 34.

5 “Indians Turn Camp Cheerful Into ‘Iwo Jima’ for Pitchers,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1970: 20.

6 “Hennigan’s in Groove Again, Fireball Lifts Indian Spirit,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1971: 24.

7 “Royals’ Otis En Route to Super Star Status,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971: 3.

8 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1972: 6.

9 “Indians Tout Spikes as Super Star of Future,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1972: 58.

10 “Young Ideas by Dick Young,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1972: 16.

11 “Young Ideas by Dick Young,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1973: 14.

12 “Baseball’s Court Jesters,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1973: 14.

13 “Hennigan Leaves Tides,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1974: 38.

14 Light and Champion Obituaries, “Phillip Winston Hennigan, Sr.” June 17, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2016 (http://bit.ly/2ej1IIe ).

Full Name

Phillip Winston Hennigan

Born

April 10, 1946 at Jasper, TX (USA)

Died

June 17, 2016 at Center, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.