Byron Houck

Rare is the player in major-league history who, after being part of a World Series winner, joins an equally great team in another profession in his post-baseball life. Pitcher Byron Houck provides such an example. He was part of the Philadelphia Athletics’ championship staff in 1913, but his major-league career soon faded away. A decade later, he was in the movies — but behind the camera rather than in front of it. As a member of Buster Keaton’s production unit, Houck helped to film some of the finest moments in the silent movie era.

Rare is the player in major-league history who, after being part of a World Series winner, joins an equally great team in another profession in his post-baseball life. Pitcher Byron Houck provides such an example. He was part of the Philadelphia Athletics’ championship staff in 1913, but his major-league career soon faded away. A decade later, he was in the movies — but behind the camera rather than in front of it. As a member of Buster Keaton’s production unit, Houck helped to film some of the finest moments in the silent movie era.

Byron Simon Houck was born on August 28, 1891, in Prosper, Minnesota. He was the fifth of Arthur and Ida Houck’s six children. Arthur farmed in the small community just north of the state line with Iowa. Sometime after the turn of the century, the family moved west to Portland, Oregon. Arthur found work as a plasterer.

Byron attended Portland’s Washington High School, and emerged as a pitching ace. The undefeated squad claimed the state championship in 1909. “It is predicted,” reported a local scribe, “that Houck will some day be a twirler in one of the big leagues.”1 After graduating from high school in 1910, Houck enrolled at the University of Oregon. He made the Oregon baseball team as a freshman and caught the attention of Joe Cohn, the owner of the Northwestern League’s Spokane Indians. Cohn signed him on July 26, 1911.2 Houck went 4-4 over 14 games with the Indians. Per Cohn’s advice to Connie Mack, the Philadelphia Athletics drafted the youngster that September.3

The Athletics were two-time defending world champions, with five veteran starters returning for the 1912 campaign: Jack Coombs, Eddie Plank, Cy Morgan, Chief Bender, and Harry Krause. Houck was a raw project. “How different young players look on the field from the glowing recommendations that a manager receives about them,” Mack sighed as spring training began.4 With his senior catcher, Ira Thomas, he started the hopeful process of molding the youngster into big-league material. “Houck may need a little seasoning,” observed Philadelphia sportswriter William Weart.5

Somewhat bowlegged, Houck stood 6-feet and weighed 175 pounds.6 A right-hander, he possessed “a peculiar cross-fire delivery.”7 His “sharp-breaking curve ball” drew more praise than his fastball.8 Houck’s most noteworthy characteristic on the mound was the speed — or lack of it — with which he worked. He would eventually be called “the slowest boxman in baseball.”9

As the 1912 season progressed, Krause and Morgan proved mostly ineffective, while Coombs lost time to injury. Houck made his major-league debut on May 15, starting against the visiting White Sox. In 6⅓ innings, he yielded five hits and six walks. Houck contributed strong relief efforts against the Browns on May 21, and the Red Sox three days later. Mack gave him another start in Boston on May 28. Houck didn’t survive the first inning. Over the next five weeks, he sporadically appeared in relief.

On July 2 Houck entered the starting rotation. From this point forward, his performance improved, and Philadelphia won 10 of his 15 starts. But Boston ran away with the AL flag. The Athletics finished in third place with a 90-62 record. Houck finished with an 8-8 mark and a 2.94 ERA (and a retrospectively calculated ERA+ of 106, with anything over 100 being considered better than average).

It was a credible rookie campaign. That August Houck initially was mentioned as one of several Athletics to be dealt to the International League’s Baltimore Orioles for outfielders Eddie Murphy and Jimmy Walsh. Mack re-engineered the trade so as to retain the young pitcher.10 During the offseason, Houck re-signed with Philadelphia for $2,100, a $600 raise from his rookie salary.11

Houck was not the only young arm Mack had stockpiled. The Athletics’ 1913 staff also featured 24-year-old Carroll Brown, 20-year-old Joe Bush, 19-year-old Herb Pennock, 22-year-old Bob Shawkey, and 22-year-old Weldon Wyckoff. In the season’s opening series, Coombs was lost to illness, which kept him shelved all year. Not wanting to overwork Plank and Bender, Mack told the team he would pull pitchers with regularity.12 For the first time in baseball history, three pitchers — Bender, Bush, and Houck — on the same staff compiled at least 20 relief appearances. Mack’s strategy helped the Athletics cruise to the pennant.

But Houck regressed in his sophomore season. In his first start, on April 21 vs. Boston, “there was scarcely a minute during the entire fuss that Byron wasn’t planted on the brink of a yawning abyss.”13 Somehow, despite yielding eight hits and nine walks over 8⅔ innings, Houck escaped with the victory. Sometimes he lost composure. On June 11 at St. Louis, he took a 1-0 lead into the eighth inning. After walking the leadoff hitter, Houck cleanly fielded a bunt “but for some unknown reason failed to chuck to [Eddie] Collins, who covered first, for which oversight he was soundly berated by the aforesaid Mr. Collins.”14 Frank Baker then had the ball knocked out of his glove at the front end of a double steal. With the next batter Houck missed a high return from catcher Wally Schang, and the tying run crossed the plate. After Houck almost launched a wild pitch to the next batter, Mack sent in Bender. Philadelphia went on to lose the affair, 5-2.15 Other times, such as a July 10 relief stint in Cleveland in which he surrendered two hits and four walks in one inning, “Houck rendered a decidedly unchampion-like display of hurling.”16

For a two-month stretch starting in late July, Houck pitched with greater control and confidence, and won six straight decisions. A strong showing in his final appearances might have earned him pitching opportunities in the coming World Series against the Giants. But he was shelled in a relief appearance in Boston on September 26, yielded 12 hits in a complete-game loss to the Red Sox the next day, and “was as wild as a March hare” in three innings against the Yankees in the regular-season finale.17

By comparison, Bush finished strong and earned a World Series start. Houck saw no game action, and Philadelphia dispatched New York in five games. He finished the 1913 season with a 14-6 mark. In addition to his 4.14 ERA (an ERA+ of 67), Houck issued an alarming 122 walks in 176 innings.18

Houck began the 1914 season with three abbreviated, unimpressive starts. With the other youthful pitchers progressing, he was expendable, and Mack released him to Baltimore. Houck refused to report, and instead signed with the Federal League’s Brooklyn Tip-Tops. His new three-year contract was for $3,500 per season.19

Tip-Tops manager Bill Bradley immediately fit his new recruit into the starting rotation. Houck lost his first four starts, then Brooklyn lost each of his next four appearances. “Byron Houck just can’t lose the wild habits he contracted while a member of the Athletics,” groused a Brooklyn sportswriter.20 Houck pitched better as the summer progressed. But after an outing in Kansas City on August 20, Bradley ignored him for the remainder of the season. With the Tip-Tops in 1914, Houck amassed a 2-6 mark and a 3.13 ERA (an ERA+ of 102) in 92 innings.

Lee Magee replaced Bradley for the 1915 season and had no interest in retaining Houck. The pitcher, fearing the club might not honor his contract, reported for spring training. Brooklyn sent him down to the Colonial League, a circuit the Federal League had recently financed. Houck began with New Haven, which soon dealt him to Pawtucket. He finished 14-8 in Colonial League action. After the season, Brooklyn settled the remaining year of his contract by paying him half of it, then released him.21

As Houck had never signed with Baltimore, he was still Philadelphia’s property as the 1916 season approached. But Mack had no interest and, after no contract came his way by March 1, Houck became a free agent.22 He signed with Portland of the Pacific Coast League. With the Beavers in 1916, Houck went 17-19 with a 3.36 ERA.

In 1917 he struggled out of the gate. Houck had occasionally used a spitball since high school.23 With his career in jeopardy, he doctored the ball with determination. “Houck shines the ball on one side and applies saliva to the other side,” explained a local sportswriter.24 He was soon “pitching the best ball of his career” in Portland.25 Capping an improbable comeback, the St. Louis Browns drafted Houck that September. He finished his 1917 season with a 23-15 record and a 2.21 ERA.

Yet Houck’s return to the majors in 1918 was unimpressive. He mostly pitched out of the bullpen and by July “had notions of quitting the team but was talked out of it.”26 He finished the campaign with a 2-4 record and a 2.39 ERA (an ERA+ of 114) in 71⅔ innings. Houck worked, and pitched, for the Tacoma Foundation Shipyards that fall.

The PCL’s Vernon Tigers purchased Houck from St. Louis in February 1919.27 Several months later, movie comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle purchased the team and became its president. His business manager, Lou Anger, was installed as the team’s general manager. Neither possessed any particular baseball experience, but no matter. Arbuckle and his fellow screen clowns — including his protégé Buster Keaton — kept crowds in stitches with in-game routines.28 The Tigers cruised to the pennant. Houck finished with a 19-16 record and a 3.88 ERA. He added another two victories in the Junior World Series against the American Association’s St. Paul Saints.

After the 1919 season, Houck began working as a cameraman. His entrée into this new profession seems to have been based on family connections. In 1913 he had married Kittye Isaacs. His wife’s sister, Sophye Barnard, a noted vaudeville entertainer, was married to Anger.29 Contemporary reporting, or later scholarship, does not identify what studio Houck initially worked with.30 It may have been at Paramount with Arbuckle. It may also have been at Keaton’s independent production unit.

Houck put aside moviemaking to return to Vernon for the 1920 season. That summer scandal engulfed the team. Tigers first baseman Babe Borton was accused of offering bribes to Salt Lake City players to throw games in the previous season’s PCL pennant race.31 Borton implicated many of his teammates. Houck, he claimed, was present at a meeting at Anger’s home when the bribes were planned.32 Borton was expelled. Houck, and most of his teammates, avoided any punishment. Vernon again won the pennant. Houck finished with a 10-17 record and a 2.62 ERA.

Houck’s baseball career wound down. He pitched some semipro ball in 1921, then came back unimpressively to PCL action for a few weeks in 1922. Mention of Houck’s participation in a movie crew over this span is rare.33 Kittye was afflicted with chronic encephalitis, and died in March 1923.34

Soon after, Houck was a regular on Keaton’s film crew. He was photographed on the set of The Balloonatic, and was mentioned as working on Our Hospitality.35 “But you had to play baseball to work with Keaton,” a documentarian notes; “he’d pick up a bat at the slightest excuse, and in the most unlikely places.” Stills exist of batter and pitcher on top of a train car during the making of The General.36 In the fall of 1923, Houck “threw a wicked and deceptive ball” for the Keaton nine.37

Houck earned photography credits, alongside Keaton’s first cameraman, Elgin Lessley, for two 1924 classics: Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. He also was credited alongside Lessley for Seven Chances (1925). For Keaton’s masterpiece, The General (1926), Houck was an uncredited camera operator and still photographer.

In the silent era, in addition to managing photography, a first cameraman was often also responsible for lighting and developing film. A second cameraman such as Houck worked alongside a first cameraman such as Lessley in shooting scenes. The first camera created the domestic negative, the second camera the foreign negative. Both usually worked with comparatively slow orthochromatic film. “Consequently,” film historian Kevin Brownlow wrote, “accuracy with focus and exposure was imperative.” The cranking of the camera required great skill. Undercranking resulted in a speeded-up action, comparatively rare in Keaton’s movies but an added value to chase scenes. Finally, Brownlow noted, special effects such as fades, dissolves, and superimpositions “were the responsibility of the cameraman.”38

Camerawork on a Keaton set went beyond this norm. Film scholar David Thomson noted: “It has been argued, with justice, that his films are ‘beautiful,’ which means that their comedy is expressed in photography that is creative, witty, and excited by the appearance of things. That sounds obvious, but most comedy films of the silent era did little more than film the comedian’s ‘act.’”39 Lessley lit a stage scene in Sherlock Jr. to appear as a movie screen, then used surveyor’s tools to create a surreal sequence of cuts as Keaton (whose character is a movie-theater projectionist) leapt into the movies. The Navigator’s underwater scenes were shot in the clear, chilly depths of Lake Tahoe. Lessley and Houck filmed from a specially designed box lowered into the lake. Lest it mist up from their body warmth, ice was packed around them. The scenes of Keaton on The General’s moving trains required the camera crew to shoot from another train running on parallel track.40

Scandal destroyed Arbuckle’s career in the early 1920s. By mid-decade, with the assistance of friends like Keaton, he attempted a return. Houck may have also felt loyalty toward Arbuckle, or wished to take on the duties of a primary cameraman. Whatever the case, for a handful of the shorts Arbuckle directed as “William Goodrich” for Educational Pictures in 1925 and 1926, Houck served as his cameraman. They were cheaply produced and unremarkable.

Arbuckle’s comeback with Educational fizzled out. After The General, Keaton began to lose creative control of his work. Houck was remarried in 1927, to Rose Carr. His career as a cameraman apparently ended. He disappeared from movie credits, and references to his involvement in production units ceased as well. Houck remained in Los Angeles. City directories and census records indicate he sold paper boxes. In his free time, Houck played golf and was actively involved with the Association of Professional Ball Players of America.

Byron and Rose eventually relocated to Eugene, Oregon. Then, in 1956, they moved to Santa Cruz, California. He remained active with the local Grange and assisting cancer patients. On June 17, 1969, Byron Houck died from septicemia after years of suffering from kidney disease.41 He was buried in Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles. Rose survived him. Neither of his marriages produced any children.

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

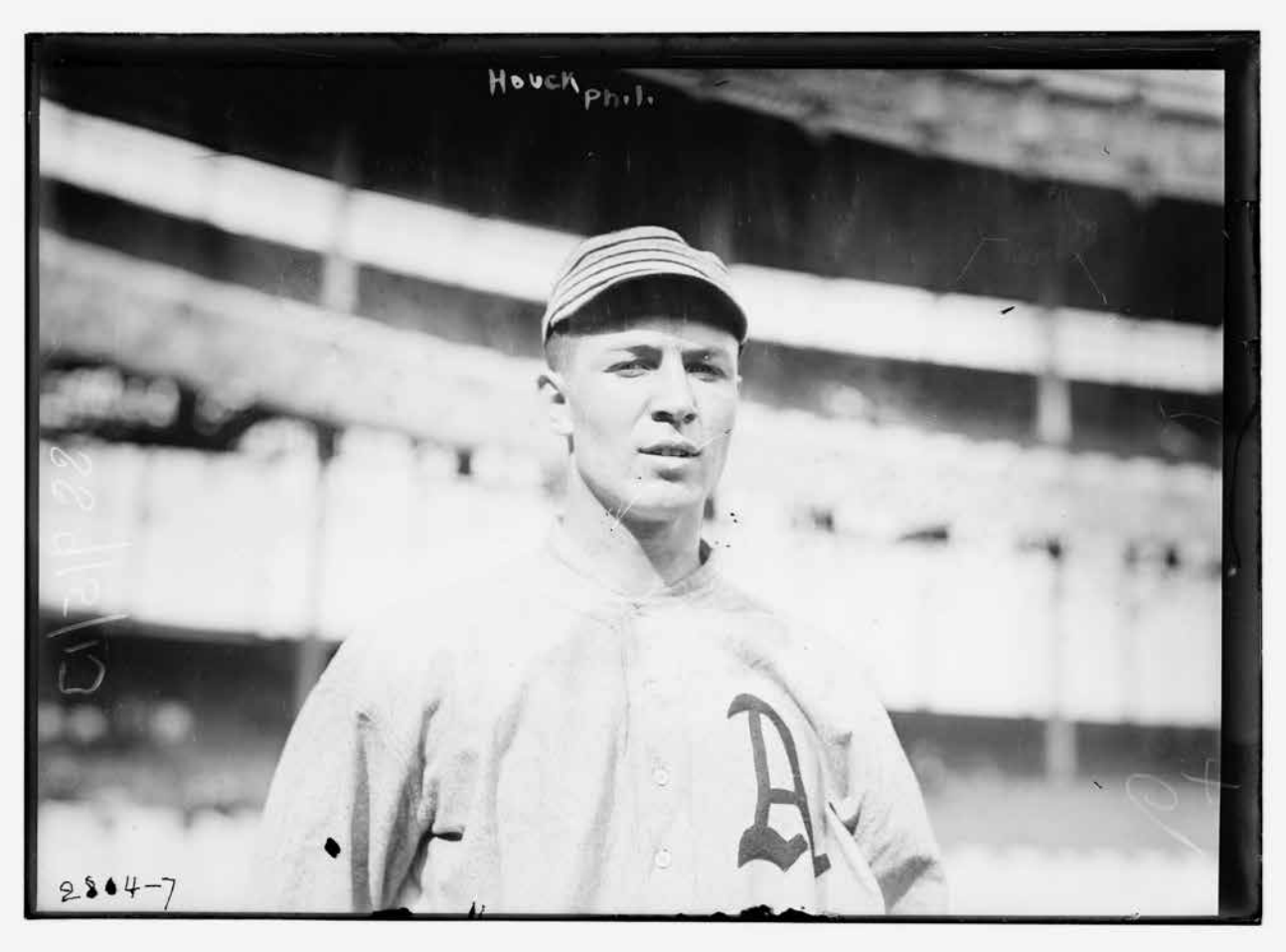

Photo Caption

Byron Houck may have compiled an undistinguished 26-24 major league pitching record, but he worked as a cameraman on a number of classic Buster Keaton silent films.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Houck’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and a number of sites such as ancestry.com, baseball-reference.com, cdnc.ucr.edu, chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers, genealogybank.com, imdb.com, newspapers.com, oregonnews.uoregon.edu, and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Champs Win Again,” Oregonian, June 3, 1909.

2 “Byron Houck Will Toss for Spokane,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), July 26, 1911.

3 “Houck Makes Hit with Connie Mack,” Oregonian (Portland), April 9, 1912.

4 William G. Weart, “Quaker Fans Quit,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1912: 1.

5 William G. Weart, “Jinx Rests on Phils,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1912: 1.

6 Back home in Oregon, he was sometimes called “Bandy Legs.” See “Byron Houck with Philadelphia Team,” Eugene (Oregon) Guard, February 15, 1913.

7 J. Ed Grillo, “Nationals Should Improve Position From Now On,” Washington Evening Star, July 3, 1912.

8 William Peet, “Batting Rally in Eighth Defeats Athletics,” Washington Herald, July 3, 1912.

9 “Bob Dunbar’s Sporting Comment,” Boston Herald, November 6, 1917.

10 William G. Weart, “Mack Not Done Yet,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1912: 1.

11 Per the salary card in Houck’s Hall of Fame file.

12 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007), 580-581.

13 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Byron Houck Would Have Scored Shutout Over Red Sox with Perfect Support by the Fielders,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 22, 1913.

14 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Agnew’s Homer With Two On in the Ninth Was Cause of it All,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 12, 1913.

15 Ibid.

16 “Macks Unable to Tame Lanky Cy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 1913.

17 “Yankees Quit Cellar by Grace of Mack,” New York Tribune, October 5, 1913.

18 Or 6.24 walks per 9 innings. No other pitcher hurling at least 150 innings in a season in the Deadball Era averaged over 6 walks per 9 innings.

19 “Brooklyn Feds Get Houck,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 21, 1914; Francis C. Richter, “The World Champions,” Sporting Life, May 30, 1914: 10. On his salary, see “Houck, Out in Cold, Despairs of Game,” Oregonian, November 5, 1915.

20 “Brooklyn Feds Lose a Close Game,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 10, 1914.

21 Chandler D. Richter, “Athletic Affairs,” Sporting Life, April 3, 1915: 6; “Federal League Facts,” Sporting Life, April 24, 1915: 10; Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 228-231; “Adams Football Player as Well,” Pawtucket Times, June 2, 1915; Pawtucket Times, October 4, 1915; Wm. J. Granger, “Brooklyn’s Finish,” Sporting Life, October 9, 1915: 9; “Houck Sells Contract,” St. Louis Star and Times, November 1, 1915.

22 “Many Fed Players Made Free Agents,” Oregonian, January 20, 1916; Roscoe Fawcett, “Byron Houck Now on Portland Roll,” Oregonian, March 2, 1916.

23 For an early mention of his spitter, see “Columbia Boys Crack Players,” Oregon Daily Journal, March 22, 1908. But at no juncture before 1917 was Houck referred to as a spitballer per se.

24 “Spit Ball Is Big Aid,” Oregonian, September 9, 1917.

25 “Portland Manager Has Mind on Next Season,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1917: 5.

26 “Cards’ Spurt Fails to Stir Community,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1918: 2.

27 “Byron Houck to Pitch Balls on Vernon Payroll,” Oregon Daily Journal, February 3, 1919.

28 For an overview of Arbuckle’s time leading the Tigers, see Greg Merritt, Room 219: The Life of Fatty Arbuckle, The Mysterious Death of Virginia Rappe, and the Scandal That Changed Hollywood (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013), 186-188.

29 For this background, see Reed Heustis, “Madman Runs Fat Arbuckle’s Studio — Sure, It’s Lou Anger,” Los Angeles Herald, November 3, 1919.

30 A valuable synopsis of Houck’s movie career may be found in Lisle Foote, Buster Keaton’s Crew: The Team Behind His Silent Films (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014), 21-25.

31 For an overview of the scandal, see Dennis Snelling, The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 83-94.

32 “Borton’s Tale Is Related to Jury,” Oregonian, October 19, 1920.

33 The only such mention the author found was for the John Gilbert drama Calvert’s Valley. See “Rim of the World,” San Bernardino Daily Sun, September 4, 1921.

34 Foote, Buster Keaton’s Crew, 23.

35 Foote, Buster Keaton’s Crew, 199; “Sport-O-Graphs,” Oxnard Press-Courier, August 30, 1923.

36 Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, “Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow, Part 2.” This acclaimed three-part television documentary from 1987 is as of 2017 available on YouTube. For more on Keaton and baseball, see Rob Edelman, “Buster Keaton: Baseball Player,” as published in the 2011 The National Pastime, https://sabr.org/research/buster-keaton-baseball-player, accessed December 1, 2016.

37 “Oxnard Defeats Keaton Team in Airtight Pitcher’s Battle,” Oxnard Press-Courier, October 22, 1923.

38 Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968), 211-221.

39 David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 471.

40 Brownlow and Gill, “Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow.”

41 Foote, Buster Keaton’s Crew, 24.

Full Name

Byron Simon Houck

Born

August 28, 1891 at Prosper, MN (USA)

Died

June 17, 1969 at Santa Cruz, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.