Bob Shawkey

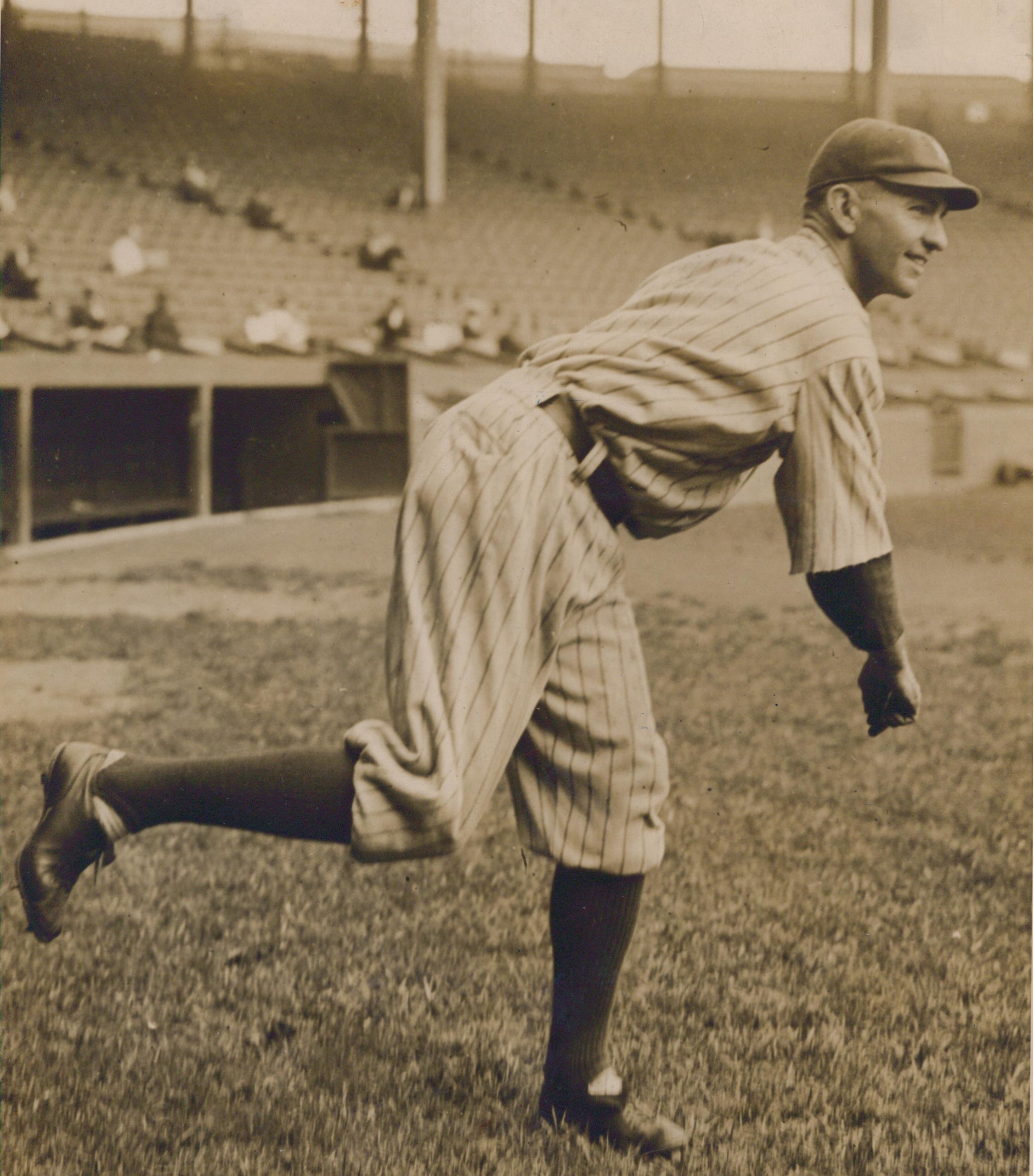

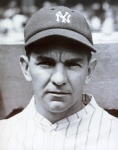

Prior to 1923, the largest attendance at a baseball game was 47,373 at Game 2 of the 1916 World Series. This record was shattered on Opening Day, April 18, 1923, when 74,200 fans filled the brand-new Yankee Stadium to see the New York Yankees play the Boston Red Sox. The Seventh Regiment Band, led by John Philip Sousa, played the national anthem, and New York Governor Alfred E. Smith threw out the ceremonial first pitch.1 The noise produced by the crowd was overwhelming. Yankee manager Miller Huggins selected 32-year-old Bob Shawkey as his starting pitcher. Amidst the din and excitement, Shawkey coolly delivered a complete game and allowed only three hits in a 4-1 Yankee victory. He singled in the third inning and scored the first run, and Babe Ruth smacked the first home run, in the stadium that became known as “The House That Ruth Built.” This game was “the greatest thrill of my life,” said Shawkey.2

Prior to 1923, the largest attendance at a baseball game was 47,373 at Game 2 of the 1916 World Series. This record was shattered on Opening Day, April 18, 1923, when 74,200 fans filled the brand-new Yankee Stadium to see the New York Yankees play the Boston Red Sox. The Seventh Regiment Band, led by John Philip Sousa, played the national anthem, and New York Governor Alfred E. Smith threw out the ceremonial first pitch.1 The noise produced by the crowd was overwhelming. Yankee manager Miller Huggins selected 32-year-old Bob Shawkey as his starting pitcher. Amidst the din and excitement, Shawkey coolly delivered a complete game and allowed only three hits in a 4-1 Yankee victory. He singled in the third inning and scored the first run, and Babe Ruth smacked the first home run, in the stadium that became known as “The House That Ruth Built.” This game was “the greatest thrill of my life,” said Shawkey.2

A four-time 20-game winner, Shawkey played on seven American League champion teams and won 195 games over 15 seasons. “He has a beautiful fastball with a great hop to it,” said Amos Rusie.3 Shawkey was also known for his sharp-breaking curveball. One of the smartest pitchers in baseball, Shawkey kept a mental book on hitters and their tendencies.4 “Pitching,” he said, “is first and last a study of the batter and a never-ending effort to give him something that he doesn’t want.”5 “Sailor Bob” (aka “Bob the Gob”6) Shawkey served in the Navy in World War I. He taught baseball in Japan with Ty Cobb, and he mined for gold in Canada. He was industrious, adventurous, and affable.

James Robert “Bob” Shawkey was born on December 4, 1890, in Sigel, Pennsylvania. He was descended from German immigrants named Schaake. Bob’s father, John William Shawkey (1861-1942), was a farmer, lumberman, and gas-line digger. When Bob was ten years old, his mother, Sarah Catherine “Kate” Anthony (1867-1901), died of tuberculosis.7 Bob and his three sisters grew up on the family farm amid the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania. As a teenager, he worked in lumber camps, cutting and hauling logs.8

Shawkey attended the Slippery Rock State Normal School during the Spring 1910 semester9 and pitched for the school baseball team. According to the school yearbook, he was known “for the number of people he can strike out in one game.”10 While playing that summer for a semi-pro team in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, Shawkey was spotted by scout Charles “Pop” Kelchner11 and signed to a contract with the Philadelphia Athletics.12 In 1911, Shawkey pitched for the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Senators of the Tri-State League. He went to spring training with the Athletics in 1912 but struggled with his control, so manager Connie Mack sent him to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League to “lose his wildness.”13 Mack requested Shawkey’s return to the Athletics in July 1912, but Baltimore manager Jack Dunn refused because Shawkey was pivotal to the Orioles’ pennant chase.14 Shawkey led the International League with 317 innings pitched that season. The next year he pitched 189 innings for the Orioles before joining the Athletics.

On July 16, 1913, Shawkey made his major league debut with the first-place Athletics, allowing two runs in seven innings to the Chicago White Sox. He shut out the Detroit Tigers in his third start and pitched a two-hitter against the second-place Cleveland Indians in August. He admired Mack and veteran pitchers Chief Bender and Jack Coombs who mentored him. “I was throwing too much with my arm,” said Shawkey. Bender “showed me how to get my body into it.”15 Bender and Coombs declared the 22-year-old phenom to be “one of the finds of the game.”16 The Athletics needed only three pitchers (Bender, Eddie Plank, and Joe Bush) to win the 1913 World Series against the New York Giants. After the Series, Shawkey drove home to western Pennsylvania in a new grey Stutz Bearcat sports car and received a hero’s welcome.17

In 1914, Shawkey’s record was 15-8. In April he went the distance against the Red Sox in a 13-inning, 1-1 tie. He pitched a three-hit shutout against the Yankees in July and delivered another three-hit shutout in August against the Washington Senators. The Athletics won the pennant again and were heavy favorites against the Boston Braves in the World Series. In a stunning upset, the Braves swept the Athletics by defeating Bender, Plank, and Bush in the first three games, and by beating Shawkey in Game 4 by a score of 3-1. Shawkey’s double off Braves pitcher Dick Rudolph knocked in the lone Athletics run in the finale.

Shawkey’s first wife was Anna Finnie Blauser (1887-1950), a schoolteacher in western Pennsylvania who bore Shawkey his only child, daughter Dorothy (1912-2008). A new woman entered Shawkey’s life in 1914. She was Marie Lakjer (pronounced “look here”), a divorcee known to Philadelphians as the “Tiger Lady” for her “massive robe of tiger skins” and matching hat which she wore about town.18 Lakjer made headlines in 1910 when she shot her wealthy husband, Herbert Mason Clapp, in the head. She was charged with “aggravated assault and battery with intent to kill,”19 but she claimed self-defense and the charges were dropped. Clapp survived and the couple divorced. “She is not afraid of a gun, man, or the devil,” said Clapp.20 Lakjer had trouble written all over her, but love can be blind: In November 1914 the 23-year-old Shawkey married the 31-year-old Lakjer in Philadelphia.21 Shawkey’s teammate Amos Strunk was the best man.

Shawkey was acquired by the Yankees midway through an uninspired 1915 season. His 1916 season was outstanding: a 17-10 record in 27 starts, plus a 7-4 record and league-leading eight saves in 26 relief appearances. His 24 wins were second in the AL behind Walter Johnson, and his 2.21 ERA ranked eighth in the league. Shawkey’s work as both a starter and reliever in 1916 was unusual: The only other pitcher in major league history to start at least 24 games, and finish at least 24 games as a reliever, was Mordecai Brown in 1911. Shawkey “is beyond any doubt one of the best right-handers in the game,” wrote Grantland Rice.22 Shawkey attributed his success in 1916 partly “to the fact that he drove his high-power racing car in moderation.”23 He left the vehicle at home in the spring so that it would not be a distraction.

In 1917, Shawkey’s record fell to 13-15 although his ERA was 2.44. During World War I, he hoped to be exempt from the draft because he was married; however, his wife refused to sign an affidavit acknowledging her financial dependence on him. “I want him to go to war, the sooner the better,” she said.24 After a quarrel, she threw him out of the house, and she “cast out upon the icy sidewalk” two trunks of his clothes, two deer heads, his “coterie of dogs,” and his sister.25 Shawkey divorced the Tiger Lady in June 1918.26

The Navy recruited major leaguers to play on shipyard baseball teams. This appealed to Shawkey, and in April 1918, he enlisted as a chief yeoman.27 He worked as an accountant and pitched at the Philadelphia shipyard.28 Miller Huggins persuaded him to pitch a couple games for the Yankees during a furlough, and on the Fourth of July, Shawkey undiplomatically shut out the Washington Senators in Washington. This did not sit well with the Navy brass, and soon he was aboard the USS Arkansas battleship in the North Sea, where German U-boats lurked. His “punishment” was a remarkable experience, culminating in the surrender of the German fleet in November 1918 – “the greatest sight I ever saw,” said Shawkey.29 Compared to sea duty, “baseball is a life of indolence and ease,” he said.30

In his return to major league baseball, Shawkey won 20 games for the third-place Yankees. Although he never pitched a no-hitter, he came close twice in 1919 with one-hitters against Philadelphia and Chicago. Beginning on May 29, he reeled off ten consecutive victories, until Stan Coveleski and the Indians defeated him 2-0 on July 9. Shawkey struck out 15 Athletics in his final start of the season. His 15 strikeouts in one game stood as the Yankee team record for 59 years, until Ron Guidry fanned 18 in a 1978 game.

Babe Ruth, as a member of the Red Sox, hit three home runs off Shawkey in 1919: a grand slam in June; a game-winning two-run homer in July; and a game-tying solo shot in September which broke Ned Williamson’s record for home runs in one season. The last one sailed out of the Polo Grounds and was believed to be the longest home run in the stadium’s history. It “went so far that Ruth could have whirled around the bases and scored a dozen runs before the ball could be retrieved.”31 What relief Shawkey must have felt when the Yankees acquired Ruth in the offseason.

On May 1, 1920, the “Ruth-less” Red Sox were “utterly unable to do anything with the delivery of Shawkey,” wrote a reporter after a Shawkey shutout.32 In 1920, Shawkey again won 20 games, including eleven consecutive victories from May 12 to July 23. His 2.45 ERA was the best in the league. The Yankees finished three games behind the first-place Indians, despite Shawkey’s 6-1 record and two shutouts against the Tribe. His greatest nemesis was Indians outfielder Elmer Smith. “I couldn’t seem to fool him,” said Shawkey. “He would hit me no matter what I gave him.”33 Six of Smith’s 70 career home runs were launched off Shawkey’s pitches. “He was a good fastball pitcher,” said Smith, “but I hit him like I owned him.”34 Another nemesis was Clarence “Tillie” Walker, who hit eleven of his 118 home runs off Shawkey.35

Shawkey’s fine 1920 season had one notable disruption. On May 27, he lost his cool with home-plate umpire George Hildebrand. Pitching against the Red Sox with a full count and the bases loaded, Shawkey walked in a run on a questionable “ball four” call, which led to a prolonged argument. He struck out the next batter to end the inning but continued his protest, so Hildebrand threw him out of the game. Shawkey became so enraged that he rushed at Hildebrand, swinging his fists. While it is unknown whether Shawkey landed any punches, Hildebrand clearly whacked Shawkey on the side of the head with his umpire mask; Shawkey bled from a wound behind his left ear.36 Sportswriters considered Shawkey to be one of the finest gentlemen in baseball and were surprised by the incident.37 AL president Ban Johnson suspended Shawkey but reinstated him a week later after the remorseful pitcher submitted a letter of apology and paid a fine.38 In his next start, with none other than George Hildebrand behind the plate, Shawkey pitched a complete game, allowing six hits in a 5-4 victory over the Athletics. In 1924, Hildebrand ejected Shawkey from two more games, without fisticuffs.

In the spring of 1921, Shawkey was bothered by a sore arm, which forced him to pitch side arm for much of the season.39 His record was 18-12, but his ERA rose to 4.08. The Yankees scored a whopping 6.4 runs per game in his 31 starts. Shawkey himself batted .300 that season, and in June, he hit his first major league home run off 27-game-winner Urban Shocker of the St. Louis Browns. The Yankees won their first pennant, but the Giants defeated them in the World Series. While Carl Mays and Waite Hoyt pitched brilliantly for the Yankees in the Series, yielding five earned runs in 53 innings, Shawkey allowed seven earned runs in nine innings and was the losing pitcher in Game 6. In 1922, Shawkey returned to top form with shutouts against Washington and Philadelphia in his first two starts. He won 20 games for the fourth time and his 2.91 ERA was third best in the league.

The Yankees won the pennant again in 1922, finishing one game ahead of the Browns. On July 13, 1922, the Browns and Yankees met at the Polo Grounds, but the game was postponed by a violent electrical storm. Lightning struck the wooden flagpole and exploded it into pieces. One piece nearly hit Shawkey as it fell to the ground. The Yankees’ AL championship pennant, which was tethered to the pole, landed in the Harlem River.40 The next day the unflappable Shawkey defeated Shocker in a 4-0 shutout. On August 28, Shawkey and Shocker went the distance in an eleven-inning, 2-1 Yankee victory. The Yankees led the Browns by a mere half game on September 16 before Shawkey outdueled Shocker for a third time. With the Yankees ahead by one run in the sixth inning, the Browns’ George Sisler, batting .420, stepped to the plate with one out and runners on first and third. Shawkey coaxed the dangerous Sisler into a ground-ball double play to end the threat, and the Yankees won the game by a score of 2-1. When Sisler was asked in 1930 to name a play that stood out in his memory, he cited this inning-ending double play, which he felt may have cost the Browns the pennant.41 In the 1922 World Series, the Giants again defeated the Yankees. In Game 2, Shawkey and the Giants’ Jesse Barnes pitched a 10-inning, 3-3 tie. The game ended controversially when Umpire Hildebrand called it on account of darkness with “a good 20 minutes of sunlight left.”42

Including the Opening Day victory at the new Yankee Stadium, Shawkey went 5-0 with a 1.04 ERA against the last-place Red Sox in 1923. His record against the rest of the league was 11-11 with a 4.27 ERA. The Yankees won the pennant and again faced the Giants in the World Series. With the Giants leading two games to one, Shawkey started Game 4 and shut out the Giants through seven innings, stranding nine baserunners. The Giants scored three runs in the eighth inning, but the Yankees prevailed to tie the Series. The Yankees won the next two games to win their first world championship.

Including the Opening Day victory at the new Yankee Stadium, Shawkey went 5-0 with a 1.04 ERA against the last-place Red Sox in 1923. His record against the rest of the league was 11-11 with a 4.27 ERA. The Yankees won the pennant and again faced the Giants in the World Series. With the Giants leading two games to one, Shawkey started Game 4 and shut out the Giants through seven innings, stranding nine baserunners. The Giants scored three runs in the eighth inning, but the Yankees prevailed to tie the Series. The Yankees won the next two games to win their first world championship.

For each season from 1919 through 1924, Shawkey ranked in the top four in the American League in strikeouts. During that period, he accumulated 743 strikeouts, and only Walter Johnson had more strikeouts (761) among AL hurlers. Shawkey “worked slowly and methodically” on the mound43 in a “steady, unemotional manner.”44 He was “the most maddening deliberate pitcher I ever saw,” said Waite Hoyt.45 Shawkey’s walk rate was average for a major league pitcher and noticeably higher than the walk rates of other elite pitchers. In games in which he walked six or more batters, though, he was “effectively wild” with a 14-7 record and 2.87 ERA.

In 1924, Shawkey again went 5-0 against the Red Sox and 11-11 against the rest of the league. At age 33 he was the eldest member of the Yankee pitching staff (he called himself “The Old Man”46), and he served as the team’s unofficial pitching coach. The Yankees finished in second place, two games behind the Senators. The next season the Yankees plummeted to seventh place. Shawkey’s 6-14 record in 1925 was partially due to poor run support: The Yankees scored 3.0 runs per game in his starts, compared to 5.8 runs per start over the previous four seasons. Despite the team’s struggles, Shawkey pitched “his heart out.”47 Before a June game, he was given an automobile by appreciative fans.48 In October, Shawkey returned to Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, for a pair of exhibition games he organized between members of the Yankees and Detroit Tigers. He was “the idol of local fans” who remembered his contribution to the 1910 Bloomsburg team.49 A week later, he was honored by a Shawkey Day in his hometown of Brookville, Pennsylvania.50

Throughout his career, Shawkey wore a red flannel long-sleeve shirt beneath his short-sleeve jersey. This was no ordinary undershirt: It was redder than a rose and as intense as a “desert sunset,”51 and he was famous for it. His bright sleeves made him easy to spot at the ballpark. Damon Runyon called him “Mr. Red Sleeves.”52 In 1928 Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs, and other Yankees followed suit with their own red undershirts.53

Shawkey held dual roles of pitcher and pitching coach in 1926 and 1927. He started Game 6 of the 1926 World Series and gave up seven runs; the St. Louis Cardinals “pounced on Shawkey like a wildcat on a tame white rabbit,” wrote one reporter.54 While he was no longer the pitcher he once was, he mentored the team’s young pitchers. George Pipgras won Game 2 of the 1927 World Series and won 24 games the next year, and he credited Shawkey for his success. “Bob taught me almost everything but how to wear a red undershirt,” said Pipgras. “He taught me control, put a hop on the fast one and added another wrinkle to the curve. Bob changed my pitching movement, too, and that improved my effectiveness a lot.”55

In November 1927, the Yankees released the 36-year-old Shawkey. After 13 seasons with the team, he held Yankee career records for wins, innings pitched, strikeouts, shutouts and saves. As of 2013, his 168 wins as a Yankee have been exceeded by only five Yankee pitchers: Whitey Ford (236), Red Ruffing (231), Andy Pettitte (219), Lefty Gomez (189), and Ron Guidry (170). Shawkey pitched for five pennant-winning Yankee teams.

In 1928 Shawkey was a pitcher and pitching coach for the Montreal Royals of the International League. He returned to the Yankees in 1929 as a full-time pitching coach. After the 1928 season, he traveled to Japan with Ty Cobb, catcher Fred Hofmann, and umpire Ernie Quigley, to teach baseball and participate in exhibition games. Herb Hunter, baseball’s “ambassador” to Japan, arranged the trip.56 Shawkey, Cobb and Hofmann played for the Daimai team, affiliated with Osaka’s Mainichi Shimbun newspaper, in a series of games against teams of the Tokyo “Big 6” college league. A baseball clinic at Waseda University attracted 4,000 attendees, and the games drew 20,000.57 (The average attendance at a major league game in 1928 was 7,000.) “I loved it in Japan,” said Shawkey. “It was amazing how keen they were on baseball.”58 The Japanese ballplayers were “great fielders and throwers,” he observed, but they needed work on their hitting.59

Shawkey considered Cobb to be the greatest hitter of all time; Cobb batted more than .400 against him.60 Although they were rivals in the American League for 15 seasons, they were friendly off the field and went hunting together.61 Shawkey was an expert hunter. Each autumn he led a moose-hunting expedition into the wilderness of Maine, New Brunswick or Quebec, accompanied by a “herd” of baseball friends, including Hofmann, Babe Ruth, Joe Bush, Eddie Collins, Benny Bengough, Sam Jones, and Herb Pennock.62 Shawkey was also an accomplished golfer. He golfed in Florida every winter and during breaks in spring training, and he was known as the golf champion of the Yankees.63 Golf Illustrated pictured Shawkey and Ruth on the links in Jacksonville in 1920.64 In a golf match at Coral Gables in 1930, Shawkey and umpire Bill Klem defeated the team of Ruth and Alfred E. Smith; the former governor lost the 1928 U.S. presidential election, too.65

Miller Huggins died in September 1929, and Yankee coach Art Fletcher filled in as the team’s manager for the final eleven games of the season. Fletcher was offered but declined the job of managing the 1930 Yankees. The job was offered to Shawkey who accepted it. Shawkey considered Huggins to be a “very good friend”66 and “marvelous teacher.”67 Replacing the man who led the Yankees to six pennants in the previous nine seasons was an enormous challenge. The 1929 Yankees finished 18 games out of first place and were trending downward. One pessimistic reporter wrote that the team is “in the throes of disintegration and rehabilitation.”68 Of particular concern was the team’s pitching; the team ERA went from a league-best 3.20 in 1927 to 4.19 in 1929. Shawkey had no managerial experience, and the skeptics asked, “If Huggins couldn’t lead this team to the pennant in 1929, how is Shawkey going to do it in 1930?” Although Ruth hoped to manage the Yankees someday, he expressed enthusiastic support for Manager Shawkey.69

Under Shawkey’s leadership, the Yankees were only two games out of first place at the end of June with a 42-25 record. They went 44-43 after June and ended up in third place, 16 games behind the first-place Athletics. The 1930 Yankees scored the most runs in one season (1,062) since the 1895 Philadelphia Phillies, but the team ERA jumped to 4.88. Shawkey did a reasonable job under the circumstances, but when the Chicago Cubs fired their experienced manager Joe McCarthy, the Yankees quickly hired McCarthy to lead the 1931 team. McCarthy’s hiring came as a shock to Shawkey who was greatly disappointed that he was not allowed to continue as manager.

One of the most significant contributions Shawkey made to the Yankee franchise occurred in 1930 when he convinced the Yankee ownership to acquire a 25-year-old Red Sox pitcher named Charles “Red” Ruffing, despite Ruffing’s lackluster 39-96 career record and 4.61 ERA. Shawkey recognized Ruffing’s potential, and he showed Ruffing how to get his body into his pitches, in the same way that Chief Bender instructed Shawkey in 1913.70 Ruffing went on to have a Hall-of-Fame career, including a 231-124 record and 3.47 ERA for the Yankees, and helped the Yankees win seven pennants in the 1930s and early 1940s.

From 1931 to 1935, Shawkey managed the Jersey City Skeeters and Newark Bears of the International League (both teams were Yankee affiliates) and the Scranton Miners of the New York-Pennsylvania League. He managed future Yankees Johnny Allen, George Selkirk and Spud Chandler. At Newark, Shawkey managed Jimmy Hitchcock, who was a baseball and football star at Auburn University.71 Hitchcock married Shawkey’s daughter Dorothy in 1938.

Shawkey left baseball after the 1935 season to manage the gold mine he purchased in 1931.72 The Shawkey Mine is near a remote town in Quebec, Canada, named Val-d’Or (“Valley of Gold”), 370 miles northwest of Montreal. There were 140 men employed at the mine in 1937.73 The operation grew so large that the Canadian government established a post office at the site with the address of “Shawkey, Quebec.”74 Bob set up a baseball field for his employees’ summer recreation. The mine yielded an estimated 42,000 ounces of gold,75 worth approximately $1.5 million in 1940 ($50 million in 2013), before it was closed due to escalating costs of production during World War II.76 Exploratory surface drilling in 2002 found gold-bearing veins at the site.77

In 1924, Shawkey married Hazel Jacqueline Bolton of Denver, Colorado; she died of pneumonia in 1931.78 In 1943, he married Gertrude Weiler (1895-1987) of Syracuse, New York, and resided with her in Syracuse. During World War II, he worked for General Electric, building radios for the Army.79 After the war, he managed the Watertown (New York) Athletics, Tallahassee (Florida) Pirates, and Jamestown (New York) Falcons. He was a roving minor league pitching instructor and scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates and Detroit Tigers in the late 1940s. “Watch the Phillies – they’re the team of tomorrow,” said Shawkey in 1948 after seeing the Phillies’ top prospects;80 Philadelphia’s “Whiz Kids” won the National League pennant in 1950. Shawkey coached the Dartmouth College baseball team from 1952 until his retirement in 1956.

In 1958, Shawkey was asked to name his all-time American League all-star team. He chose Walter Johnson as his pitcher; Hal Chase at first base; Eddie Collins at second base; Buck Weaver at shortstop; and Jimmy Collins at third base. He chose four outfielders – Cobb, Ruth, Joe Jackson, and Tris Speaker – and three catchers: Wally Schang, Bill Dickey, and Mickey Cochrane.81 Schang was Shawkey’s catcher for eight seasons.

Shawkey returned to Yankee Stadium for many special events and old-timers’ games. He was present in 1939 when Lou Gehrig gave his farewell speech82 and in 1948 when Babe Ruth made his final appearance.83 Shawkey pitched the first game ever played at Yankee Stadium, and in 1973, he threw the ceremonial first pitch at the stadium’s 50th anniversary celebration, using the same ball that Governor Smith threw in 1923.84 In 1976, the 85-year-old Shawkey again threw out the first pitch when the stadium reopened after a two-year renovation.

Shawkey struck gold throughout his life. In 1967, Syracuse journalist Bill Reddy wrote that Shawkey “won friends by the hundreds and never lost his quiet pride in having worn the Yankee uniform.”85 The steadfast Yankee died in Syracuse on December 31, 1980, at the age of 90.

Notes

1 New York Times, April 19, 1923.

2 Baseball Digest, August 1978.

3 Escanaba (Michigan) Daily Press, May 4, 1922. Amos Rusie was a Hall-of-Fame pitcher for the New York Giants in the 1890s.

4 Oakland Tribune, September 24, 1927.

5 Baseball Magazine, July 1926.

6 “Gob” is a slang term used to refer to a sailor in the U.S. Navy.

7 Email from relative Dick Shawkey, and information from http://www.shawkey.com.

8 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout (Chicago: Follett, 1977).

9 Registrar Record Group, Slippery Rock University Archives, Slippery Rock University. The records indicate that Shawkey attended only one semester at the Slippery Rock State Normal School.

10 The Anamnisis, Slippery Rock State Normal School Yearbook, Volume 1 (Columbus, Ohio: Champlin Press, 1910). Shawkey and his baseball teammates are pictured in the yearbook.

11 Ron Smiley and Jim Sandoval, “Pop Kelchner,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b028c8f6.

12 Sources disagree on whether the Athletics signed Shawkey before or after his season at Harrisburg.

13 Sporting Life, April 20, 1912.

14 Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, July 24, 1912.

15 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout.

16 Boston Globe, July 17, 1916.

17 Kane (Pennsylvania) Republican, October 21, 1913.

18 Pittsburgh Press, October 3, 1914.

19 John E. Reyburn, Annual Report of the Mayor of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Dunlap Printing, 1911).

20 Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, December 13, 1910.

21 Pittsburgh Gazette Times, November 17, 1914. Marie Lakjer’s age in 1914 was determined from her 1910 U.S. Census record.

22 Boston Globe, July 17, 1916.

23 Sporting Life, December 16, 1916.

24 Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, January 10, 1918.

25 Boston Globe, January 6, 1918.

26 El Paso (Texas) Herald, June 14, 1918.

27 New York Sun, April 3, 1918.

28 Attica (Indiana) Daily Tribune, September 20, 1918.

29 New York Sun, January 4, 1919.

30 New York Tribune, January 29, 1919.

31 New York Times, September 25, 1919.

32 Boston Globe, May 2, 1920.

33 Baseball Magazine, July 1926.

34 Salt Lake Tribune, July 30, 1958.

35 http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/event_hr.cgi?id=shawkbo01&t=p.

36 New York Times, May 28, 1920.

37 Kansas City (Kansas) Star, June 13, 1920.

38 The Sporting News, June 24, 1920.

39 Bob Shawkey, interviewed by Eugene C. Murdock, April 15, 1975.

40 Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner, July 14, 1922.

41 Kokomo (Indiana) Tribune, January 15, 1930.

42 The Sporting News, October 13, 1962.

43 Robert Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built: A New Stadium, the First Yankees Championship, and the Redemption of 1923 (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 2011).

44 New York Evening Post, May 19, 1924.

45 Mason City (Iowa) Globe Gazette, April 14, 1944.

46 Bridgeport (Connecticut) Telegram, March 27, 1924.

47 Hamilton (Ohio) Evening Journal, June 30, 1925.

48 Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune, June 11, 1925.

49 Columbia County (Pennsylvania) Historical and Genealogical Society, http://colcohist-gensoc.org/wp-content/uploads/111playball.pdf.

50 New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, October 14, 1925.

51 Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, May 4, 1928.

52 Buffalo Courier-Express, October 10, 1926.

53 Ironwood (Michigan) Daily Globe, March 21, 1928.

54 Oakland Tribune, October 10, 1926.

55 Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1927.

56 Bill Nowlin, “Herb Hunter,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/06f2e2e9.

57 Oakland Tribune, December 13, 1928.

58 Syracuse (New York) Post Standard, February 15, 1971.

59 Syracuse Herald, January 25, 1929.

60 In May 2014, Retrosheet.org showed Cobb’s career batting average against Shawkey as .449; however, this figure was computed from incomplete data.

61 Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, January 28, 1927.

62 Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, October 16, 1925, and Oakland Tribune, November 23, 1926.

63 Hattiesburg (Mississippi) American, March 19, 1925.

64 Golf Illustrated, April 1920.

65 Syracuse Herald, January 18, 1930. Smith lost the 1928 U.S. presidential election to Herbert Hoover.

66 Bob Shawkey, Murdock interview.

67 Brooklyn Eagle Magazine, November 24, 1929.

68 Huntingdon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, October 22, 1929.

69 Tyrone (Pennsylvania) Daily Herald, March 3, 1930.

70 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout.

71 William Akin, “Jim Hitchcock,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4d0a4ffc.

72 Wichita Falls (Texas) Daily Times, December 23, 1931.

73 Medicine Hat (Alberta) News, June 14, 1937.

74 Medicine Hat News, January 18, 1937.

75 Canadian Mining Journal, September 2005.

76 Mount Vernon (New York) Daily Argus, April 17, 1943.

77 http://www.infomine.com/index/properties/SHAWKEY.html.

78 The Sporting News, January 22, 1931.

79 Portsmouth (New Hampshire) Herald, June 1, 1943.

80 Wisconsin State Journal, August 6, 1948.

81 Syracuse Herald Journal, April 6, 1958.

82 Olean (New York) Times-Herald, July 5, 1939.

83 The Sporting News, June 23, 1948.

84 The Sporting News, May 5, 1973.

85 Syracuse Herald-American, February 19, 1967.

Full Name

James Robert Shawkey

Born

December 4, 1890 at Sigel, PA (USA)

Died

December 31, 1980 at Syracuse, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.