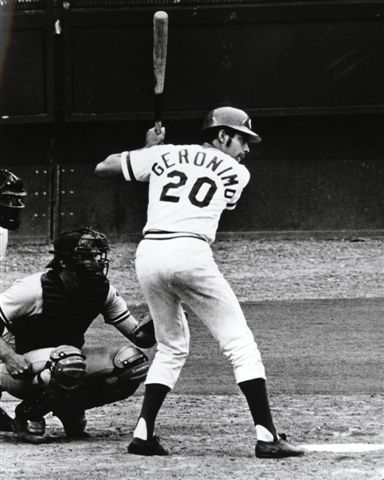

Cesar Geronimo

Playing on a squad that featured such top-rank stars as Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and Tony Perez made it challenging for other players to gain notoriety in their own right. During the 1970s it was easy to overlook the contributions of “other” Reds who made up the roster of the Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine. While Cesar Geronimo is sometimes slighted in the eyes of the media and public, his exceptional arm, glove, and range in center field, and his timely hitting, helped him play an essential role in bringing two World Series titles to the Queen City. Indeed, his career was marked by historic events: Geronimo scored one of the most significant and controversial runs in World Series history in 1975 and holds one distinction (as a strikeout victim) unlikely ever to be repeated by a major-leaguer. Once he retired after the 1983 season, Geronimo began contributing to the sport in another way: by improving the lot of Dominican youngsters who were pursuing their dreams (athletic, academic, and personal) against what were often overwhelming odds.

Cesar Francisco (Zorilla) Geronimo was born on March 11, 1948, in the municipality of Santa Cruz de El Seibo, El Seibo Province, Dominican Republic. While it was quite common for Dominican children of this era to not receive much formal schooling, Cesar’s parents worked diligently so that their son would not only be properly educated, but would serve the Catholic Church as a priest. With this aim, Cesar was enrolled in the Santo Tomas de Aquino seminary at the age of 12 and remained there for five years. Eventually he withdrew and attended (and graduated from) high school. His father was quite happy, for he had wanted his son to pursue an athletic career. Throughout his time in these settings, there was one constant in Cesar’s life: a love of baseball, and particularly the New York Yankees. “I liked it at seminary, but I really wanted to be a ballplayer and I knew if I went on to become a priest that would never happen,” he once said.1

Neither the seminary nor his high school fielded a baseball team, so Cesar instead played basketball, soccer, and slow-pitch softball (on a club with his father). Geronimo’s success on this squad, predominantly because of his strong throwing arm, led to tryouts with the New York Mets and the Yankees, and the Yankees signed the 19-year-old prospect in 1967 as a pitcher-outfielder. (While blessed with phenomenal arm strength, he was awful at bat.) His first two teams were in rookie leagues: Oneonta in the New York-Pennsylvania League and Johnson City (Tennessee) of the Appalachian League. His lack of hitting was evident at both locales. Geronimo played four games for Oneonta and hit a meager .100, followed by an even more anemic .071 in 19 games for Johnson City. The next season the Yankees moved him to Fort Lauderdale in the Florida State League hoping he would find something resembling a reasonable stroke. While there was some improvement, it was marginal (a .194 average in 109 games and 324 at-bats) and the notion of moving Geronimo permanently to the mound gained acceptance.

At about this time Geronimo came to the attention of Grady Hatton, a scout for the Houston Astros, who recommended the outfielder to his boss, assistant general manager John Mullen. Then, at the 1968 winter meetings, Howie Haak, a scout for the Pirates, raved to Mullen about Geronimo’s arm and bemoaned the fact that Pittsburgh did not have room on its roster for the young Dominican. The conversation clinched Mullen’s interest, and the Astros invested $8,000 on the unproven prospect, selecting Geronimo in the third round of the Rule 5 draft.2

The Astros, as required by the draft rules, kept Geronimo on the major-league roster for the entire 1969 season, using him mainly as a late-inning defensive replacement and pinch-runner. Geronimo got into only 28 games and had eight at-bats (two hits). For 1970, no longer required to keep him in the majors or risk losing him, the Astros assigned Geronimo to their Columbus (Georgia) affiliate in the Double-A Southern League, where he hit a more respectable .269 in 74 games, and called him up for 47 games (37 at-bats) late in the season. Geronimo played winter ball and continued to work on both his hitting and fielding. Heading into the 1971 season, the Astros felt he could be useful as a pinch-runner and pinch-hitter. And there were those who believed that “if he were a regular, he would be the best fielder on the team.”3 He justified the Astros’ faith in his defensive prowess by launching a strike from the left-field corner of the Astrodome to nail Duke Sims of the Dodgers at third base on Opening Day. But at the plate, while he had a few good stretches, he hit only .220 in 94 games (82 at-bats). Once again, he headed off to play winter ball in hopes of continuing to improve all facets of his game.4

Geronimo’s statistics in Houston were certainly not dazzling, and he was now playing behind All-Star center fielder Cesar Cedeno, but once again fate intervened to boost his career prospects. In late November 1971 the Cincinnati Reds negotiated a swap that sent first baseman Lee May, second baseman Tommy Helms, and utilityman Jimmy Stewart to the Astros in exchange for second baseman Joe Morgan, infielder Denis Menke, pitcher Jack Billingham, outfielder Ed Armbrister, and Geronimo. For some, the young Geronimo seemed little more than a throw-in. Reds general manager Bob Howsam, however, argued that because the Reds had moved to the spacious Riverfront Stadium, it was necessary to have outfielders with speed who could cover more ground.

Finally given an opportunity to play semi-regularly, and helped by extensive work with batting instructor Ted Kluszewski, Geronimo improved to .275 in 120 games (255 at-bats) in 1972, many as a late-innings replacement. With the fleet veteran Bobby Tolan returning from an injury and manning center field, Geronimo mainly played right field that season. Once again, he played winter ball, and began the 1973 season as the Reds’ center fielder, with the now struggling Tolan shifting to right. Geronimo injured his shoulder while making a catch and then slumped badly to .210. There was some reason for hope, as he had raised his average from .149 in July, and hit over .300 in September. Anderson argued that Geronimo was still an asset to the Reds. “If a guy can save you a couple of runs with his fielding and throwing, it is just as important as driving home a couple of runs.”5

After that dismal campaign, Geronimo again headed home to the Dominican Republic to play baseball, where he got some well-timed assistance from his manager, Tommy Lasorda. The work paid off, as Geronimo hit .281 in 150 games for the Reds in 1974 and earned the first of what would be four consecutive Gold Glove Awards. On July 17 he became the 3,000th strikeout victim of Bob Gibson, a feat he oddly duplicated on July 4, 1980, when he was the 3,000th victim for Nolan Ryan. Given his seminary training, Geronimo was very philosophical about this “feat”: “I was just at the right place at the right time,” he said.6

In 1975, in his second full season holding a regular position, Geronimo hit .257 and led the NL in outfield putouts with 408. In the World Series against the Boston Red Sox, Geronimo scored the winning run in Game Three, leading off the bottom of the 10th inning with a single, moving to third after a controversial collision between Boston catcher Carlton Fisk and pinch-hitter Ed Armbrister, and scoring on a single by Joe Morgan. For the Series, hit .280 (7-for-25) with two home runs, as the Reds won the classic in seven games.

Geronimo had his best individual season in 1976 as he hit .307 with 11 triples, second in the league. The Reds again waltzed to the World Series and swept the Yankees. Geronimo batted .308 while playing every inning for the second straight October.

Geronimo hit .266 with a career-high ten home runs in 1977 and copped his fourth Gold Glove award, but the Reds were overtaken by the Dodgers in the NL West, and many of the team’s regular players began to depart. Perez had been traded after the 1976 season, and Rose and Morgan soon left for free agency. Geronimo stayed with the Reds through the 1980 season, but his hitting fell to .226, .239, and .255, and he was a part-time player most of that time.

In January 1981 the Reds dealt Geronimo to the Kansas City Royals for infielder German Barranca. Geronimo played the final three years of his career mainly as a defensive replacement, compiling only 324 at-bats and hitting .244 He played his final game in the majors on August 28, 1983, against the Texas Rangers. The Royals released him after the season. In 1,522 major-league games he batted .258 with 51 home runs, and 392 RBIs.

Geronimo was always known as a quiet and reserved individual, who brought much stability and class to the Reds’ locker room. He and his wife, Elizabeth, were married in 1971 and had two children, Cesar Jr. (born December 19, 1972) and Giselle (born December 17, 1975).7 Given his religious training, it is not surprising that Cesar got involved in causes linked to social justice after his departure from the majors. First, he was involved with the Federacion Nacional de Peloteros Professionales, which represented the interests of Dominican ballplayers in their dealings with the teams on the island. Later, he worked at the training camp set up on the island by the Hiroshima Toyo Carp of the Japanese baseball league, a facility that Mark Kurlansky in his book The Eastern Stars called “one of the better appointed academies” on the island.

Geronimo also was a founder and a board member of the Dominican Republic Sports and Education Academy, aimed at providing proper training, nutrition, and on-field instruction to young Dominican athletes, and working to make sure they are educated, have a working knowledge of English, and are given basic instruction in financial matters.8

In other words, Cesar Geronimo continued to do the same caliber of work that he performed with the Reds during the Machine’s glory days. He was not about bringing great attention to himself. He merely did the best he could to make it possible for his team (and then his countrymen) to succeed in the often-difficult world of baseball. While he never became a Catholic priest, in many ways in recent years he was involved in a type of ministry that his Jesuit instructors at the Santo Tomas de Aquino seminary would certainly approve. The Cincinnati Reds inducted him into their Hall of Fame in 2008.9

Last revised: December 1, 2018

An earlier version of this biography was included in SABR’s “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C. Baseball’s Great Dynasties: The Reds (New York: Gallery Books, 1991).

Frost, Mark. Game Six: Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America’s Pastime (New York: Hyperion, 2009).

Hertzel, Bob. The Big Red Machine (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1976).

Lawson, Earl. Cincinnati Seasons: My 34 Years with the Reds (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1987).

McCoy, Hal. The Relentless Reds (Shelbyville, Kentucky: PressCo, 1976).

Posnanski, Joe. The Machine: A Hot Team, A Legendary Season, and a Heart-Stopping World Series: The Story of the 1975 Cincinnati Reds (New York: William Morrow, 2009).

Walker, Robert Harris. Cincinnati and the Big Red Machine (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1988)

Notes

1 Ritter Collett, Men of the Machine: An Inside Look at Baseball’s Team of the 1970s (Dayton, Ohio: Landfall Press, 1977), 210.

2 Jim Ogle, “Inside Pitch: Light Hitting Geronimo Provided Yank Surprises,” April 10, 1971; part of the Cesar Geronimo file at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and Stan Isle, “Hurlers Are Hottest Items in Majors’ Draft,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1968: 33-34.

3 The Sporting News, March 27, 1971: 39-40.

4 John Wilson, “Astros Toughen 6 Arms on Florida Pad,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1969: 53; ; “Astros Beat War Drums for Geronimo,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1971: 39-40; “Dodgers Learn Geronimo Boasts Rifle for an Arm,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1971: 8; and “Farmhands Fuel Strongest Astro Drive of Season,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1971: 22.

5 Earl Lawson, “Sure Hands Cesar Wins Cincy Salute,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1972: 21 and 28.

6 Mark Purdy, “Mild Mannered Cesar Often Misunderstood During 9 Years As Red,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 18, 1981. Both items are from Cesar Geronimo file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

7 Cesar Geronimo pages, 1980 Cincinnati Reds Media Guide, 36, 37.

8 “The Champs of ’75,” Sports Illustrated, July 31, 2000; Alan M. Klein, Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 41, 55. Mark Kurlansky, The Eastern Stars: How Baseball Changed the Dominican Town of San Pedro de Macoris (New York: Riverhead Books, 2010), 197. For more information on the Dominican Republic Sports and Education Academy (DRSEA), visit the organization’s website at: www.drsea.org. Here, you can also download copies of their publication, “DRSEA Informer.” For more information on the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, visit www.japanball.com/carp.htm.

9 Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame, Member Directory; Cesar Geronimo, Class of 2008. http://mlb.mlb.com/cin/hof/hof/directory.jsp?hof_id=114723.

Full Name

Cesar Francisco Geronimo Zorrilla

Born

March 11, 1948 at El Seibo, El Seibo (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.