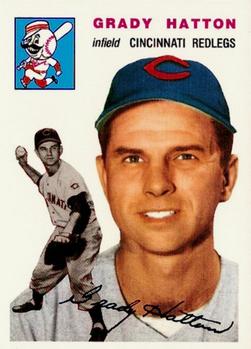

Grady Hatton

If not for two years of military service and four years at the University of Texas, baseball lifer Grady Hatton’s career as player, manager, scout, and front office executive would have surpassed a half century. Mainly a third baseman, he played in 12 big-league seasons (1946-56; 1960). Reflecting on his playing career in 1966, Hatton stated that scouts didn’t give him much chance to succeed. “I was an average ballplayer. I could do a lot of things pretty good, but wasn’t outstanding in any phase of the game.”1

If not for two years of military service and four years at the University of Texas, baseball lifer Grady Hatton’s career as player, manager, scout, and front office executive would have surpassed a half century. Mainly a third baseman, he played in 12 big-league seasons (1946-56; 1960). Reflecting on his playing career in 1966, Hatton stated that scouts didn’t give him much chance to succeed. “I was an average ballplayer. I could do a lot of things pretty good, but wasn’t outstanding in any phase of the game.”1

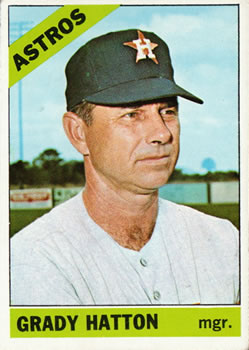

Hatton was known for his great personal integrity. In 1956, the Boston Traveler raved about this, noting the nickname “Grade-A” and saying that “there should always be a place for him as a coach or manager…Any young player lucky enough to be associated with Grady must have some of that big league quality rubbed off on him.”2 Indeed, two years later he started his minor-league managing career, which lasted for seven seasons. He then led the Houston Astros from 1966 through June 1968.

Born on October 7, 1922 in Beaumont, Texas, Grady was the first child of native Texans Grady Edgebert Hatton Sr. and Ada Anne Goolsbee. Seven years later his sister, Joada, was born. Their father was a pipefitter for 40 years at the Magnolia Petroleum Company oil refinery in Beaumont.

As a youngster, Grady Jr. threw left-handed and batted from the right side. But his father believed he would not be tall enough to play in the outfield or first base and made him throw from the right side (and bat lefty).3

Hatton was the shortstop for Beaumont High School and played guard for the football team. He played American Legion ball and worked out with the Texas League Beaumont Exporters after school and before their day games. At age 15, he was given a chance to play in the Evangeline League (Louisiana) for $65/month. However, his father nixed the deal.4 Longtime University of Texas coach “Uncle Billy” Disch recruited Hatton to play for the Longhorns, offering him a partial scholarship his freshman year with the potential for a full ride after that.5 Hatton entered UT in 1939.

Working toward a degree in physical education, Hatton earned All-Southwest Conference baseball honors three times (third baseman in 1941 and 1943, and shortstop in 1942). Texas took the SWC championship in both 1941 and 1943; Grady was team captain in his final season.6 He also played running guard for the Longhorn football team for one season. Hatton was inducted into the Longhorn Legion of Honor (UT Hall of Fame) in 1967.7

In addition to his collegiate play, Hatton played shortstop for the semipro Waco Dons (1941-1942). In 1948, Jinx Tucker (sports editor of the Waco News-Tribune) named him to the all-time Waco baseball team.8

Early in his stay at Texas, Hatton received an offer of $15,000 from Branch Rickey to sign with the Cardinals. Grady showed the offer to his coach, who “ripped it up right before my eyes,” after it was determined that the offer was closer to $1,500 because of its many clauses.9 Coach Disch did some scouting for the Red Sox and recommended him. Hatton traveled to Fenway Park in Boston, where he worked out for manager Joe Cronin.10

With World War II under way, the 20-year old Hatton enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in December 1942, but was sent back to school two weeks later. However, in May 1943, he was recalled into service two hours short of a degree from Texas and sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. The following month he was dispatched to the Overseas Replacement Depot (ORD) in Greensboro, North Carolina. There he served for three years as a physical training instructor and played on the ORD baseball team.11 That squad played in the National Semi-Pro tournament in Wichita twice, finishing third each time.

While in the service, Hatton signed a $15,000 contract with Cincinnati.12 However, Commissioner Kenesaw Landis declared that any contract signed by a serviceman was illegal, making Hatton a free agent.

On February 13, 1946, Sergeant Hatton received his discharge. His stock had gone up while he was playing service ball. The Plain Dealer in Cleveland reported that 15 of 16 major-league clubs put in bids for his services. The Dodgers reportedly offered him $35,000. But, feeling bound by his prior commitment, he drove to Cincinnati, where he met with GM Warren Giles, who advised him that he was not obligated to sign with the Reds. Hatton told Giles, “I shook hands on the deal. The contract was just a piece of paper. If that one isn’t legal get another one and I’ll sign again. I have no intention of signing with another club.” Giles appreciated Hatton’s integrity so much that he added another $5,000 to the contract.13

Hatton also received a $25,000 bonus – “the largest amount,” said Giles, “ever paid to a rookie to tie up with a National League club.” Hatton used it to buy 455 acres of land near Warren, Texas. In a 1952 interview, Hatton talked about his ranch, where he owned 40 range cows. His father drove 52 miles from Beaumont on weekends to look after his prize stock. He used the same ranch brand (a “J”) as his grandfather.14

Going straight to the major leagues, the 23-year-old appeared in 116 games in his first season under manager Bill McKechnie. His debut was strong; on April 16 he was 3-for-5 (all singles) off the Cubs’ Claude Passeau with two runs batted in. However, despite the positive personal results, Hatton’s last at-bat would be what he remembered most from the game.15 With the Reds down, 4-3, in the bottom of the ninth, two outs, and the bases loaded, Hatton hit a line drive that backup shortstop Al Glossop caught ranging far to his right. Hatton was disappointed that he didn’t come through in the clutch.

His rookie season was good. He finished 18th in the National League MVP voting, leading sixth-place Cincinnati in batting average (.271), the last Reds rookie to do so, RBIs (69), and home runs (14, good for seventh in the NL). On the basis of OPS+, (127), he had arguably the second-best season in major-league history by a rookie third baseman after Ryan Braun of the 2007 Brewers (153).

Hatton’s statistics were even more impressive considering that his season ended over a month early after an accident at Crosley Field on August 24. He fractured his right kneecap in a runway leading from the playing field to the dressing room as he ran against a brick wall. He sought to avoid spiking a little girl autograph hunter who got in his path.16 He stopped short and slid on the concrete, skidding into both the wall and Harold Parrott, the Dodgers traveling secretary.

In 1947, Hatton played in 146 of the Reds’ 154 games under new skipper Johnny Neun. He bumped up his average to .281, hitting 16 home runs and driving in 77 while scoring 91.

Hatton’s focus as a defender was visible on June 19, when his roommate Ewell Blackwell pitched a 6-0 no-hitter. After the game, Hatton made a beeline for the dugout and hadn’t noticed the throng near the mound. Teammate Elmer Riddle, a pitcher, joined Hatton in the clubhouse and enthused, “How did you like that?” Hatton asked him what he meant, and was told Blackwell had just thrown a no-hitter. “Great grief! I never even knew it.”17 Despite the apparent oversight, Blackwell (a fellow Red from 1946 to 1952) later stated that Hatton was the “nicest teammate” he played with in his career.18

In 1949 Hatton’s 38 doubles (a career high) were good for third in the league. After having dropped off to .240 in 1948, he raised his average back to .263 and hit 11 homers with 69 RBIs. He also led all NL third sackers with a .975 fielding percentage.

One morning during spring training in 1950, Hatton conducted perhaps the first baseball players’ union meeting in Reds history. Players were airing their complaints and requests to be addressed to Reds management.19 He was following in the footsteps of his father, who helped organize a union at his refinery in Texas, where he held the position of president for five years.20 Hatton would continue as the Reds’ player representative during the rest of his nine-year stay in Cincinnati and with the Red Sox in 1955.

Hatton married Dorris Mae Brannan of Beaumont on February 4, 1952.21 They had three children: daughters Dorri Jayne and Patti and son Grady III.22

Hatton had still been the Reds’ primary third baseman in 1951, but his playing time dropped off to just 96 games, missing almost a month with a broken thumb. In 1952 Cincinnati switched Hatton to second base without complaint from him. He later reflected that it had taken “five years to learn third base [and] just when his education was completed, he was moved to second.” Hatton said at the time, “Second base is five times harder than third base. It’s the meanest job in the infield. You’ve got more plays. You cover first. You handle bunts and hold your position when somebody’s sliding in to break up a double play. Shortstop doesn’t have it as tough – he is always looking at the play. A lot of times, the second baseman has the play behind him.”23 Yet despite the switch, Hatton led National League second basemen in fielding (.990).

Though he was hitting just .235 at the break, Hatton was named as a reserve infielder to the NL All-Star team by manager Leo Durocher, his only such selection. However, the game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia was called after five innings due to rain before Hatton could enter. By season’s end his average had dropped to .212, his lowest full-season mark. Still, he contributed 9 home runs and knocked in 57.

Hatton’s tenure in Cincinnati ended early in 1954. On April 18 he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for shortstop Johnny Lipon. When he suited up for the White Sox, it was the first time he’d ever worn the uniform of any other professional team. However, he started slowly in Chicago (.167 in 13 games) and his stay in Chicago was a short one (35 days).

On May 23 Hatton made his way to the Red Sox (with $100,000) for future Hall of Famer George Kell. Hatton played well for the Red Sox, batting .281 with a .399 on-base percentage in 99 games while leading American League third basemen in fielding percentage (.966). Grady wore #1 while with the Red Sox, a number previously worn by two Hall of Famers: Kell and Bobby Doerr, for whom the number was later retired by the Red Sox in 1988.24

In 1955, the Red Sox, under new manager Pinky Higgins, finished at 84-70, good for fourth place in the American League. That was the only full season in Hatton’s major-league career in which his team finished above .500. Although his average dropped off (.245 in 126 games), he managed 76 walks, bumping his on-base percentage up to a career high .399.

In 1956, for the second time in his career, Hatton saw action with three teams in one season. He was limited to five pinch-hit appearances with Boston before the St Louis Cardinals purchased his contract on May 11. Hatton saw limited action at second base for the Redbirds, serving mainly as a pinch-hitter (.247 in 73 at-bats). On August 1 the Baltimore Orioles purchased his contract for the $10,000 waiver price. After hitting .148 for Baltimore and splitting time between second and third, Hatton was released after the end of the season.25

Hatton was ready to move on to an insurance business position in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. However, the Red Sox asked if he would be willing to play for their farm team in San Francisco at the same salary he had earned in 1956. Hatton agreed. Thus, in 1957, at age 34, he played in the minor leagues for the first time in his career. Playing third base and hitting .317, he helped the Seals, led by manager and future Hall of Famer Joe Gordon, win the Pacific Coast League title in their last season in the league.26

On January 14, 1958, Hatton returned to his home state of Texas to become a player-manager with the San Antonio Missions of the Double-A Texas League. He managed there for three years. The Missions showed continuous improvement. As an Orioles farm team in 1958, they finished sixth with a record of 74-79. Becoming a Cubs affiliate, the team improved to 75-70 in 1959, finishing fourth and losing a semifinal playoff series.27

Hatton had the opportunity to become manager of the Triple-A Houston Buffs of the American Association in 1960. However, he had given a verbal commitment to the San Antonio ball club that he would return that season if they wanted him. The Missions did and he declined the better-paying offer from Houston.28

In 1960, Hatton guided San Antonio to a 50-42 record until he was called up to the Cubs as a player/coach. He appeared in 28 games, 20 of them as a pinch-hitter, batting .342.

In discussing his last at-bat in the majors, Hatton recalled, “Do you know what a role model is? Well, my role model was Ted Williams and I thought it was just the greatest thing ever when he hit a home run and then retired. What a way to bow out of the big leagues, with a home run.

“So in 1960 with the Cubs I hit a ground ball past the pitcher. Damn ball must have bounced nine times before it made it to the outfield. And know what? I announced my retirement. I retired on a single up the middle.”29 He was released by the Cubs nine days later.

In November 1960, Hatton signed on with the Houston Sports Association, the organization that owned the rights to the major-league expansion franchise in Houston (initially known as the Colt .45s). He began scouting Texas and Louisiana.30 The following season (1961), Hatton resumed managerial duties in the Cubs chain, leading the Buffs to an 8-10 record before returning to the Colt .45s organization. He became the Director of Player Personnel.31

In 1963 Hatton took over managerial duties for Houston’s AAA affiliate in Oklahoma City. In three seasons, he led the ’89ers to two Pacific Coast League division titles and subsequent pennants. In 1965 he was voted The Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year by 200 major-league scouts.32 Major-league pitcher Joe Hoerner, who pitched for the ’89ers from 1964-65, credited Hatton with advancing his career by focusing him on the bullpen.33

During the offseason, Hatton enjoyed hunting, working with his hunting dogs, and officiating basketball in the Southwest Conference. 34 Sounding an ongoing theme, The Sporting News wrote of his character after the 1965 season. “Another big word in Hatton’s personal code is honesty. His forthright attitude and his willingness to deal with writers and others on a basis of mutual trust – never breached – turns every Hatton acquaintance into an admirer.”35

Another writer who covered minor league baseball provided this insight on Hatton: “Grady Hatton is the only man I ever knew who told his daughter she couldn’t car date until she was 16 and stuck to it.”36 As a manager in Oklahoma City, following his earlier work in organizing players, he insisted that his players pay their dues to the Association of Professional Baseball Players, of which he was a 20-year member.37

In the offseason, Hatton was offered a two-year contract to manage the White Sox for $35,000 a year.38 After he received assurances from Houston owner Roy Hofheinz that his position in the organization was secure, he agreed to remain with the Colts. Helping to make his decision, Houston was 90 miles from his elderly parents in Beaumont and 100 miles from his ranch near Warren. Also, his wife had endured two criminal attacks in their apartment building in their short tenure with the White Sox in 1954, which left bad memories of their time in Chicago.

In the offseason, Hatton was offered a two-year contract to manage the White Sox for $35,000 a year.38 After he received assurances from Houston owner Roy Hofheinz that his position in the organization was secure, he agreed to remain with the Colts. Helping to make his decision, Houston was 90 miles from his elderly parents in Beaumont and 100 miles from his ranch near Warren. Also, his wife had endured two criminal attacks in their apartment building in their short tenure with the White Sox in 1954, which left bad memories of their time in Chicago.

On December 12 Hofheinz fired his general manager, Paul Richards, and farm director, Eddie Robinson, and named Hatton to succeed manager Lum Harris. The GM duties were shared among Hatton (Director of Player Personnel), business manager H.B. (Spec) Richardson, and personnel director Tal Smith.39 With many of his former Oklahoma City players on the roster, Hatton led the Astros to their best record in the team’s five-year history in 1966.

Hatton tried to bring consistency and uniformity to the Astros organization. While a manager and coach in the Cubs organization, he had authored a book called Organizational Policy, addressing all phases of playing baseball. He wanted to use it to establish a baseline for how the entire Houston organization would teach baseball. He updated the book with ideas from Astros coaches, scouts, and minor-league managers.40

This attention to detail had a flip side. Those critical of Hatton’s managerial style noted he could be critical and nagging, at times unnecessarily so in public, and could be “overly strict in his [judgments].”41

Star pitcher Larry Dierker also considered Hatton to be a very intense person, as one anecdote illustrates. One time on the off-season speech circuit with Rusty Staub, Dierker gave Hatton’s speech instead of his own, using Grady’s heavy Texan accent (e.g., help = hep). Hatton was fit to be tied, not only because all his material had been used but also because Dierker called attention to his manner of speech. Hatton spoke after Dierker, and tried a different spiel, which didn’t work. However, he persevered, and the audience laughed heartily when he said “hep” four or five times.42

Hatton had the well-being of colleagues at heart. Before the 1966 season, he called former minor-league coach Buddy Hancken and wanted to know if he was interested in managing the AA club at Amarillo. “After Buddy had his heart attack, he got out of baseball for a while. I called him up and asked him if was interested. He jumped out of his steps and I told him to get a doctor’s permit to say he was able to do it and he had the job,” Hatton said.

“Two years later [1968], I wanted him to be my bench coach at the major league level and he was able to stay on for Harry Walker for three more years after I was replaced as manager,” Hatton said. “He was a great mentor to young guys like Enos Cabell, Art Howe, and Larry Dierker.”43 As it later developed, Hatton replaced Hancken as the Astros’ first-base coach in 1973 under manager Leo Durocher.44

The highlight of the 1966 season was the opening of the Astrodome and introduction of Astroturf. Hatton trumpeted at the time, “This is the real utopia for baseball – no wind, no sun, no rain, no bad bounces.”45 It proved to be another dreary season for the Astros, though; they finished ninth in the NL.

On July 27, 1967, Roy Hofheinz named Richardson as GM and extended Hatton’s contract through the 1968 season. However, Hatton was relieved of his Director of Player Personnel duties at the same time. Hofheinz reflected that “it had been a mistake to saddle the field manager with administrative duties.” 46

In May 1968, Hatton noted the difference between being a manager and a player in the big leagues: “The hardest thing I had to learn, when I became a manager, was to be patient, never give up, especially on a young ballplayer. Have enthusiasm, work and be patient. As a ball player it’s the opposite. The player should be impatient. He has to stay mad at the world, keep pushing himself while the manager tries to take an easy look at things.”47

On June 1, 1968, Hatton had his team a mere four games behind the first-place Giants, albeit in eighth place. The NL announced that it was the tightest race ever at that point in the season (tenth-place Pittsburgh was five games behind).48 However, the Astros slumped and went 2-14 over the next 16 games. Hatton was relieved of his managerial duties on June 17 after 61 games (23-38 and 14 games out of first place) and replaced by Harry Walker; the team played just below .500 ball the rest of the season (49-52). GM Richardson called him into his room to tell him, “I got the unfortunate job of telling you you’re fired.” Hatton replied, “Okay. We’ve been friends 17 years, we’re still friends.”49

Hatton remained in the Houston organization as Special Assistant to the GM and Vice President.50 He also scouted through 1972. He returned to the field as a coach for the Astros for Leo Durocher and Preston Gomez.

In 1975, Hatton was named director of player development by the Astros until relieved of the position in October.51 This ended a 15-season run in the Houston organization. The following year he began his next career as a scout for the San Francisco Giants, a tenure lasting 16 seasons.52

As a scout, Grady was an early skeptic of “20-year old” rookie sensation Fernando Valenzuela‘s age in 1981. He told writers in Philadelphia that Fernando couldn’t possibly be 20 because he’d spotted wrinkle lines on the back of the pitcher’s neck. Ultimately, the Dodgers produced a birth certificate showing a birth date of November 1, 1960, but that failed to convince the doubters. At a press conference in Philadelphia, someone asked to see the back of Fernando’s neck.53

Hatton forecast success for the 1981 Astros, commenting in early April on their prospects for the season, “Their pitchers are going to carry them a hell of a long way.”54 The Astros made it to the postseason for the second straight year in the strike-shortened season.

Between the 1981 and ’82 seasons, Hatton’s close scouting was instrumental in the Giants’ acquisition of Bill Laskey and Atlee Hammaker from the Royals in separate trades, both of which worked out to the Giants’ advantage.55

In 1984 he offered this scouting report on the Padres’ Tony Gwynn, who was en route to his first of eight batting titles: “Tony Gwynn is vulnerable to high fastballs, but few pitchers have both the control and the velocity to get him out consistently with that formula.”56

He could also admit when an initial assessment of his was wrong. After John Tudor had an extraordinary year in 1985, Hatton said, “I never thought Tudor would be more than a .500 pitcher anywhere. He has below-average velocity, a breaking ball that’s average at best, and good control. But he put some screwball action on his changeup and [is] striking everybody out with it. I can’t understand the hitters. They keep swinging at it, and that scroogie is eating them alive. It gets ’em out easy. I don’t know why they don’t look for it.”57

Never afraid to voice his opinion, Hatton offered the following in 1988 when asked about Pam Postema, the first woman to umpire a major league game in spring training: “I’ve seen her three times this spring. Terrific behind the plate but the world’s worst on the bases.”58

The same year Hatton reminisced about playing in hot weather. He said he simply adjusted to the heat because there was no choice. “You get used to it really, is what it amounts to. They had several tricks. We used a tub and put ice and water in it. Get a big head of cabbage. We’d peel the leaves and put the leaves in the tub of ice and put it in our hat and go out and play. It sure did help. We had a water fountain but they wouldn’t let you drink. That’s what’s started everyone chewing tobacco. I’m just guessing. You get tobacco in your mouth and you didn’t want to drink.”59

Hatton retired from scouting on November 20, 1991, ending his 46-year career in professional baseball.

On May 9, 1996, Hatton was named to the all-time Southwest Conference baseball team as a utility player. Of the 17 players named to the squad, nine were alumni of his alma mater, the University of Texas.60 He received another honor on November 6, 1996, when he was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. In the same class were future President George W. Bush (former Texas Rangers owner and then Governor of Texas) and former major leaguers Cito Gaston, Roger Metzger, and Dave Philley.61

At the age of 90, and fighting cancer, Grady Hatton died at his longtime home in Warren on April 11, 2013. He was buried at Mount Pisgah Cemetery near Woodville, Texas.62 As Larry Dierker put it, “He was just a solid baseball guy … he knew the game.”63

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the authors also accessed Hatton’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Undocumented quotation supplied by Brian P. Wood.

2 Arthur Siegel, “Suffolk Downs Offers 36-Day Meet Monday,” Boston Traveler, May 12, 1956: 4.

3 The Old Scout, title ends in “…Reds’ Recruit,” unknown newspaper, c.1946, from the Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

4 Undocumented information supplied by Brian P. Wood.

5 John Wilson, “They Said Grady Was Too Little.” Disch stepped down as the head coach after the 1939 season and became an Advisory Coach through the 1951 season. “This Week,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, January 10, 1966.

6 http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/hatton_grady.htm

7 “Men’s Hall of Honor, Grady Edgebert Hatton, Jr.” TexasSports.com, http://www.texassports.com/aa.aspx?hid=156, retrieved December 28, 2016.

8 Jinx Tucker, “All-Time Waco Club Is Chosen by Scribe,” Waco News-Tribune, April 23, 1948: 45.

9 Ibid.

10 “Grady Hatton of Hawks Got Semi-Pro All-America Vote,” Greensboro Record, April 20, 1945: 10.

11 Clifford Bloodgood, “Grady Makes the Grade,” unknown newspaper, April 1947.

12 Pat Harmon, “Have Patience, Grady Hatton,” Cincinnati Post, May 22, 1968. The Baseball Hall of Fame archives lists the date as May 22, 1967. However, it was 1968 because the games behind mentioned in the article pertain to May 21, 1968, not 1967.

13 Ibid.

14 Earl Lawson, “Baseball to Ranching Hatton’s Aim,” unknown newspaper, June 16, 1952, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

15 John Wilson, “They Said Grady Was Too Little.”

16 Associated Press, “Hatton May Be Out for Rest of Season,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, August 27, 1946: 6.

17 Mickey Herskowitz, “Modesty, Sense of Humor Hatton Hallmarks,” Houston Post, April 9, 1961. Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: The Man with the Buggy-Whip Arm,” New York Times, March 9, 1948: 30. Hatton was best man at Blackwell’s wedding in August 1948.

18 “Ewell Blackwell,” http://www.thedeadballera.com/SurveySays.html, retrieved February 17, 2017.

19 Ritter Collett, “Baseball’s Union Came a Long Way,” Dayton Daily News (City Edition), DATE: 3D.

20 John Wilson, John. “The Said Grady Was Too Little.”

21 Hank Zureick, “Third Baseman Grady Hatton,” Cincinnati Baseball Club Press Release, 1952, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

22 Bob Dellinger, “Guided by Grady, Kids Bloom in a Hurry,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1965.

23 Pat Harmon, “Have Patience, Grady Hatton.”

24 “Grady Hatton,” Baseball Almanac, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=hattogr01 retrieved February 17, 2017.

25 Several sources imply he became an insurance salesman after he left the Orioles in 1956, but he continued to play & manage.

26 Pat Harmon, “New Cheers for Hatton.”

27 Baseball Hall of Fame information card on Grady Hatton, 1973, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

28 Nealon.

29 Roger Kahn, Good Enough to Dream (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 90.

30 Associated Press, “Hatton Gets Manager’s Job,” Boston Globe, February 2, 1961: 33.

31 Baseball Hall of Fame information card on Grady Hatton, 1973, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

32 Joe King, “Everybody Likes Hatton—Astros Most of All,” New York World-Telegram, January 29, 1966.

33 Bill James & Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Touchstone, 2004), 244.

34 Ibid.

35 Bob Dellinger.

36 Mickey Herskowitz, “Astros’ managers have touched a lot of bases,” Houston Chronicle (3 Star Edition), November 10, 2001: 6.

37 Ibid.

38 Associated Press, “Hatton Says White Sox Made Five-Year Offer; Club Denies It,” Boston Globe, December 11, 1965: 21.

39 John Wilson, “Richardson Astro GM; Hatton Gets New Managerial Contract,” unknown newspaper, possibly Houston Chronicle, August 12, 1967, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

40 “Right Way Is The Astros’ Way,” unknown newspaper, March 12, 1966, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

41 John Wilson, “Hatton Has ‘Spec’ and Judge in His Corner,” Houston Chronicle, August 13, 1967.

42 Larry Dierker, This Ain’t Brain Surgery (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 256.

43 Jason Rollinson, “Man of many stories: Following seven decades in baseball, Hancken’s talks will travel on, even after his recent death,” Orange Leader, February 17, 2007.

44 John Wilson, “Ex-Pilots Gomez and Hatton Join Astro Coaching Corps,” unknown newspaper, possibly Houston Chronicle, October 21, 1972, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

45 Milt Dunnell, “Non-grassers deserve their turn at plate,” Toronto Star, February 23, 1987: D1.

46 John Wilson, “Richardson Astro G-M; Hatton Gets New Managerial Contract.”

47 Harmon. “Have Patience, Grady Hatton.”

48 Harmon. “Have Patience, Grady Hatton.”

49 Steve Jacobson, “Hatton Finds Parting Is Sweet Sorrow,” unknown newspaper, unknown date, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

50 Baseball Hall of Fame information card on Grady Hatton, 1973, from Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

51 “Associated Press, “Hatton Fired by Houston,” Dallas Morning News, October 29, 1975: B6.

52 Associated Press, “Wednesday’s Sports Transactions,” November 21, 1991.

53 Mike Penner, “Ten Years Later, the Mania Resumes,” Los Angeles Times (Orange County Edition), June 7, 1991.

54 Joseph Durso, “Expos Ready To Move Up,” New York Times, April 5, 1981: S11.

55 Joe Sargis, “If There was an Award for Pitching Coach of…” UPI News Track, August 11, 1982

56 Phil Collier, “Padre Pitchers Make Believers of Astros, 6-2––Lollar, Dravecky Spin a 3-Hitter,” San Diego Union Tribune, June 21, 1984: C-1.

57 Tommy Hine, “Tudor Got A Pitching Tip and It Paid Off,” Hartford Courant, October 13, 1985: CE4

58 Jerome Holtzman, “Female Ump Figures To Get The Call, But Not This Year,” Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1988: B14.

59 Mike Tully, United Press International, “Scouting: Today’s Baseball Column,” August 16, 1988.

60 Dave King, “SWC: The End of an Era,” San Antonio Express-News, May 9, 1996: BC

61 “Texas Baseball Hall of Fame,” http://www.tbhof.org/bio/1996/biohatton_m.htm/ retrieved December 28, 2016.

62 Associated Press, “Grady Hatton dies at age 90,” April 11, 2013, http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/9162164/grady-hatton-former-third-baseman-managed-houston-astros-dies, retrieved December 25, 2016.

63 Avi Zaleon, “Former Astros manager Hatton dies at 90,” Houston Chronicle, April 11, 2013.

Full Name

Grady Edgebert Hatton

Born

October 7, 1922 at Beaumont, TX (USA)

Died

April 11, 2013 at Warren, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.