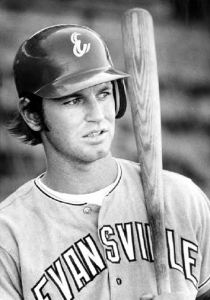

Bill McNulty

It was a scene that even a Hollywood scriptwriter might find fantastic. As baseball’s 1972 regular season entered its final week, the Oakland Athletics, preparing for their second consecutive American League division playoffs, wanted to give their regulars some much needed rest. So with the minor-league season over, management decided to call up one of the organization’s premier young power hitters, Bill McNulty.

It was a scene that even a Hollywood scriptwriter might find fantastic. As baseball’s 1972 regular season entered its final week, the Oakland Athletics, preparing for their second consecutive American League division playoffs, wanted to give their regulars some much needed rest. So with the minor-league season over, management decided to call up one of the organization’s premier young power hitters, Bill McNulty.

Only, they couldn’t find him.

With the front office unable to reach McNulty by phone or telegram, the team’s radio broadcasters resorted to the airwaves, sending out messages asking McNulty to immediately call the team. Upon hearing their pleas, McNulty’s father, Raymond, called the club and told them his son had gone hunting in the Warner Mountains of Northern California. In no time, a Forest Service airplane was dispatched to try to track down the elusive slugger.

Eventually, McNulty was located. Four decades later, he recalled, “My friends and I were sitting around a campfire … it was cold … and in walked two guys, almost literally out of the dark. Two game wardens; didn’t even see ’em coming.”

“You must be Bill McNulty,” they said.

“I am.”

“’We need you to come down to the sheriff’s office with us,” said the wardens.

And the next day, McNulty was in Oakland, wearing the green and gold Athletics uniform.

It wasn’t the first time he’d put it on, but perhaps this time he’d wear it a little longer. If anyone appeared to possess the requisite skills for baseball stardom, it was 26-year-old William Francis McNulty. Born in Sacramento, California, and raised in the suburb of Roseville, 20 miles northeast of Sacramento and about 80 in the same direction from Oakland, McNulty had been a three-sport star at Highlands High School, midway between Roseville and Sacramento, a school that also produced McNulty’s “high school hero,” fellow major leaguer Bob Oliver. (McNulty was a freshman when Oliver was a senior.) By the time he graduated in 1964, McNulty had been named Most Valuable Player of both the basketball and football teams, and had also been voted Highlands’ Outstanding Athlete. Moreover, that year, too, he’d been named to Sacramento’s All-Legion baseball team after leading his Haggin-Grant Post American Legion team to the district championship.

That McNulty, at 6-feet-4 and 210 pounds, owed much of his athletic success to natural ability was unquestionable, yet he had also been well-schooled in the fundamentals. His father, Ray, had been a minor-league star on the West Coast, playing primarily in Oregon, with Salem in the Western International League and Portland in the Pacific Coast League. Ray began his career as a third baseman, but his strong arm led to a shift to the mound, where, between 1946 and 1954, he won 85 games, an impressive complement to his .258 career batting average and 25 home runs.

Naturally, Ray exposed his son to the game at a young age. “In Dad’s last year [1954],” remembered Bill in 2013, “I was 8 years old. He took me to the games and into the clubhouse. I used to shag balls during batting practice. I couldn’t make the throw from the outfield to the infield.” Such attention, of course, gave McNulty a leg up on the competition. “When it came to baseball I was always ahead of the other kids. I got into an 8- to- 11-year-old Little League when I was 7, and made the All-Star team.” An important lesson imparted by his father was that “you never wanted to be the best player, because you never improved. You always had to find better competition. You have to go find older kids who are better than you.” (After retiring from baseball Ray worked as a car salesman; his wife, Joyce, was a homemaker.)

Once graduated from Highlands, McNulty enrolled at American River College, a two-year institution in Sacramento. It proved to be a relatively short stay. In what turned out to be his only season at the school, McNulty once again played basketball and football, and his strong arm on the gridiron gave the school’s baseball coach high hopes for the coming baseball season. However, a visit to McNulty’s home by a friend of his father’s soon altered McNulty’s course.

By virtue of his own career, Ray knew all the local baseball scouts. One was Don Pries, a fellow career minor leaguer, who was then a scout for the Kansas City Athletics. One day, Bill recalled, “I think Don contacted my dad — this would have been around January or February of ’65 — and said, ‘I’d like to come out to the house and talk to you about signing Bill.’” Accompanying Pries was John McNamara, then managing the Athletics’ Double-A affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama. That day, Bill McNulty said, the two men who “had the biggest influence on what turned out to be an [Oakland] dynasty in the ’70s” were “very persuasive”: Kansas City was in last place, they said; we’re moving to Oakland in a year or two, just about the time you’ll be ready to play in the big leagues; and you’ll be playing 80 or 90 miles from your hometown. Thus, McNulty joined the Athletics organization.

(There is one final anecdote about that afternoon. As Pries left, Ray asked “Where are you off to now?” “Well,” replied Pries, “tomorrow I’m driving down to Modesto to sign this kid named Joe Rudi.”

(“That turned out pretty good,” McNulty later recalled, with a chuckle.)

In his first season, 1965, the Athletics sent the 18-year-old McNulty (he turned 19 on August 29) to Leesburg in the Class A Florida State League, where, he recalled, he joined a “skinny kid from Cucamonga, California,” named Rollie Fingers. In 133 games McNulty made an impression on both sides of the ball, finishing first in RBIs and second in home runs, while also pacing the league’s third basemen in putouts and finishing second in double plays. Despite his .199 batting average, it was nonetheless a promising debut. That fall McNulty also fulfilled a military obligation. Beginning in October 1965, for the next six months he underwent Marine Corps Reserve training, beginning with boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruiting Department in San Diego alongside fellow players Rick Monday and Dave Duncan, then at Camp Pendleton, California, and finally to radio operator’s school. McNulty satisfied his Reserve obligations for the next six years.

The next three seasons for McNulty were marked by a steady climb through the Athletics farm system. Along the way he played with many of the men who eventually formed the core of the Oakland A’s championship dynasty. While he made occasional forays into the outfield, McNulty settled into third base and proved a better than average fielder with a rifle arm. Moreover, anchored in the middle of the batting order, the right-handed slugger also proved a powerful if sometimes inconsistent hitter.

Over that period, he made several stops. In 1966, at Burlington (Iowa), in the Class A Midwest League, McNulty was an All-Star. He led the league in fielding average and assists, and also delivered ten home runs and 60 RBIs. Promoted to Double-A Mobile for the final weeks of the season, he produced a blistering OPS (on-base average plus slugging average) of 1.413 in seven games. (Among the players on that team were Tony La Russa, Rick Monday, Sal Bando, and Rene Lachemann.) The following season, in addition to playing in the Arizona Instructional League with such future stars as Reggie Jackson, Bert Campaneris, Vida Blue, Gene Tenace, and Fingers, McNulty also played 44 games with the Peninsula Grays (Class A Carolina League), where he excelled (.307/.398/.569), and 63 at Double-A Birmingham, where the going was a little tougher (.213/.273/.370). In 1968 he returned to both of those teams, to similar levels of success (.290/.355/.515 in 54 games at Peninsula; .188/.241/.324 in 48 games at Birmingham). In those three seasons combined McNulty produced 43 home runs and 189 RBIs. His powerful performance placed McNulty emphatically on the radar of the only man who mattered in the Athletics front office, owner Charles O. Finley.

Every once in a while the game’s most promising prospects make the jump from Double-A to the majors. So it was with McNulty. Although he had struggled during his first two stints with Birmingham, in 1969 he opened the season there, and this time proved up to the challenge. By July 4 McNulty, on his way to being named the Southern League’s All-Star third baseman, had become one of the leading hitters in the league, posting a slash line of .288/.347/.568 over 75 games, while also producing league-leading totals of 20 home runs and 67 RBIs. Then, on July 7 in Chicago, Athletics outfielder Tommie Reynolds suffered a broken finger that forced him to the disabled list. To replace him, Oakland called up McNulty. Perhaps surprisingly, the 22-year-old headed to the major leagues.

In 2013 McNulty recollected with levity the day he got that first call to join the A’s. At the time Birmingham was in Charlotte, North Carolina, for a series with the Charlotte Hornets. In his hotel room around 7:30 A.M., McNulty and his roommate were awakened by a phone call. “I’m Joe Williams of the Charlotte Observer newspaper,” the caller announced. “I understand you’re having a great year, and I want to do a story about you.” To which McNulty replied, “Catch me at the ballpark,” and began to hang up. Just before he could do so, however, the caller said, “No, don’t hang up; I’ve got a deadline here.” To which McNulty responded, “What do you want?”

“Well, first of all, why aren’t you in the big leagues yet?”

“I don’t know. I guess I need a lucky break.”

“Well,” the caller countered, “you just got one. Tommie Reynolds broke his finger. My name’s Charlie Finley and you’re playing left field tonight in Chicago.”

Skeptical, McNulty confirmed the promotion with his manager, Gus Niarhos, and immediately left for Chicago. That night when McNulty arrived at Comiskey Park, a smiling Finley said to the rookie, “I really had you going, didn’t I, Bill?” and McNulty acknowledged the joke. In the clubhouse, manager Hank Bauer told McNulty, “Mr. Finley says you’re starting in left field tonight.” When McNulty protested that “I’ve never played left field in my life,” Bauer retorted, “Well, if you’re afraid, wear a helmet, because Rick Monday’ll catch anything hit near ya.” Finally, John McNamara, now an A’s coach (he succeeded Bauer later in the season) counseled, “Bill, just hit the ball, don’t worry about catching it.” So on July 9, 1969, McNulty made his major-league debut.

If McNulty worried about playing left field, he nevertheless acquitted himself well. That first stint in the majors lasted five consecutive games; McNulty started each in left field and handled 11 chances (nine putouts and two assists) flawlessly. At the plate, he never got untracked; he went 0-for-17, with ten strikeouts. Over that span, he hit just one ball out of the infield. After his tenth strikeout, on July 13, Oakland sent McNulty to the Triple-A Iowa Oaks, where he was .198/.262/.333 in 26 games. It was three years before he returned to the major leagues.

In January 1970 The Sporting News reported that the A’s had dropped McNulty from their 40-man roster.1 At Iowa he re-established himself as a legitimate power prospect, as he batted .295, finished third in the American Association in home runs (22) and RBIs (73) and was named an Honorable Mention to the league All-Star team. It wasn’t enough to impress the A’s: After the season, they sold McNulty’s contract to the Milwaukee Brewers. (The deal was for cash, “something over the Triple-A draft price,” plus pitcher Gary Timberlake.2)

Little could the slugger have foreseen the unexpected twist his career would take in 1971. With his confidence restored, he hit .333 with a home run and nine RBIs in 33 spring-training at-bats. McNulty thought he had done enough to make the team. Brewers manager Dave Bristol disagreed. In particular, he graded McNulty low in two phases: McNulty’s “lateral range at third base isn’t good enough,” Bristol told The Sporting News”; 3 and perhaps more damaging, Bristol concluded, “(T)he big thing against him is that he is lackadaisical. I’ve got to have players with fire.”4 It was a scathing assessment.

The worst was yet to come. In late March Milwaukee demoted McNulty to Triple-A Evansville. Before he left, Brewers general manager Frank Lane told him, “Young man, we’d like to have you work on becoming a pitcher at Evansville.”5 That suggestion did not interest McNulty. Recounting to the press his father’s successful transition in the minors, he nonetheless protested, “I’ve never pitched in my life and I don’t want to start at the age of 24. I want to hit — and I still think I can get to the big leagues as a hitter.”6

In the end, he never had to attempt the change. That spring, McNulty ran into Ray Johnston, owner of the Iowa Oaks. “Can’t you make a deal to get me back to Des Moines?” he said. “If I can’t play in the big leagues, I’d rather play for the Oaks than anybody else. … I know they won’t try to make a pitcher out of me.”7 Johnston, for whom McNulty had in 1970 led the Oaks in homers and RBIs, passed along McNulty’s request to Charlie Finley, and Finley bought McNulty back from Milwaukee.

McNulty repaid the gesture in a big way, and also gained the admiration of Iowa’s manager, Sherm Lollar, for whom he had produced so well the previous season. Later that 1971 season, told of Dave Bristol’s opinion of McNulty’s skills, Lollar, who had had the same impression the first time he’d seen McNulty, offered, “That seemingly nonchalant attitude of Bill’s is misleading. It’s just Mac’s physical makeup to be kind of slow-moving and casual until he has to bear down. But he’s really a good competitor and he hustles every time it counts. I tried last year [1970] to get Bill to move around more and show some fire, just to help liven up the infield. But it’s just not his nature to holler and jump around.”

Initially, Lollar had tried McNulty in the outfield, but once he moved McNulty to the infield, Lollar found him to be “just about the most exciting third baseman I’ve ever seen. Even when he didn’t field the ball clean, he’d pounce on it after he knocked it down and throw out some of the fastest runners in the league. Lots of times, I’d think the batter was going to be safe for sure, but Bill would gun him down. … He’s made it easier this year because he’s been sure-handed. And he’s been going a lot farther to make some real big league stops.”8 There wouldn’t be a second McNulty on the mound.

McNulty finished the 1971 season with impressive production. Although his batting average lagged to .247, he led the league in home runs (27) and walks, compiled a .902 OPS and was voted to the American Association All-Star team. Some of his homers were what Lollar called “some real big league home runs — 400 feet or more.”9 After some turbulent times, it appeared McNulty had righted the ship. But there were to be several more moves before the A’s tracked him down at that campfire. Two days before the end of the 1971 season, the Chicago Cubs’ Tacoma farm team, seeking help for the Pacific Coast League playoffs, purchased his contract from Iowa. Tacoma lost the five-game series, but McNulty was magnificent: 7-for-14, with three home runs and 7 RBIs. Based on that performance, he naturally assumed “there might be a chance for me with the Cubs” in 1972.10 He was mistaken.

With Ron Santo entrenched at third base in Chicago, the Cubs had little use for McNulty. They shipped him out of the organization, ironically to Evansville. It was a move that appealed to McNulty. “I don’t think I could tolerate sitting on the bench,” he said. “Maybe if I have a good season, somebody will want me.”11

McNulty did indeed have another good season and proved he was still a prospect. Playing primarily at third base, he overcame a slow start to finish second in the American Association in home runs (24) and fourth in RBIs (73). It was his third consecutive season with over 20 homers. But when Evansville’s season ended, unsure what 1973 might bring, McNulty went to the mountains to hunt. And that’s when the A’s bought his contract and brought him back to Oakland.

Asked in 2013 to try to explain his brief major-league career, McNulty said, “I don’t really know how to answer your question. I never felt overmatched. I should have stayed in the big leagues in ’69; I would have been on all those championship teams, would have progressed like Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace, my buddy… but I didn’t produce.” Recalling his first big-league at-bat in 1969 (McNulty said it was against Tommy John; according to Retrosheet.org, it came against right-hander Billy Wynne), “I decided my first at-bat that I would take the pitch. It came in there. … It looked like a basketball coming in there, right down the middle. Next pitch, he threw something similar, I was so excited to see it that I swung and hit it in the upper deck, just foul, strike two. The next pitch, I took. Ed Runge was the umpire. Sal Bando told me, ‘Don’t ever look at Runge, because he’ll run you out of the game.’ Well, he [Runge] goes ‘ball,’ and that pitch was pretty good. And I reached down to grab some dirt and he leans over and he says, ‘Don’t ever take that pitch again, kid. I did it because it’s your first at-bat.’ Well, by then, I said, I’m swinging at the next pitch, I don’t care where it is, and I swung and missed.” (Note: according to Retrosheet.org, George Maloney was the home plate umpire; Runge was at first. Also, the final pitch was a called strike three.)

By October 4, 1972, the last of his four-game major-league swan song, it seemed McNulty had finally figured it out. In his three previous games (September 27, as a pinch-hitter against Bert Blyleven, and two subsequent starts at third base against the Royals), McNulty had gone 0-for-8, striking out just once and earning his first two walks. Then, on this night against the California Angels, McNulty faced perhaps the fastest pitcher of them all, Nolan Ryan, who was trying for his 20th win of the season. In the bottom of the second, Reggie Jackson doubled and catcher Dave Duncan walked. With runners on first and second, McNulty came to the plate for his first at-bat of the night. Ryan delivered, McNulty swung, and he drilled a line drive up the middle, a clean single to center, on which Jackson was thrown out at the plate. A final at-bat two innings later resulted in a fly out to left field, and McNulty’s major-league career was over. He finished 1-for-27 over nine games, with 11 strikeouts and two walks.

McNulty hung on for a few more years, including one magical season back in his hometown. In October 1972 the A’s traded McNulty and a player to be named later (Brant Alyea) to the Texas Rangers for left-hander Paul Lindblad. McNulty went to 1973 spring training with Texas and their new manager, Whitey Herzog, but the two didn’t get along. So at the end of spring training, the Rangers traded McNulty to the New York Mets for infielder Bill Sudakis. That season, spent entirely at the Mets’ Tidewater farm team in the International League, McNulty again delivered, finishing first, second, and third respectively in doubles, total bases, and home runs. But by then, he’d had enough. When the season ended, he decided to start the next phase of his life.

At home in Sacramento, though, McNulty got good news. Pacific Coast League baseball was returning to Sacramento. After a 14-year absence from the PCL, the Solons would return, as an affiliate of the Milwaukee Brewers. McNulty visited general manager John Carbray and told him, “I’d like to play in my hometown but I belong to the New York Mets, and in 1973 they had me in Tidewater.”12 The Brewers quickly purchased McNulty’s contract from the Mets, and he became a Solon for the 1974 season.

In one of the oddities of baseball stadium configurations, the Solons played that year at the Sacramento City College field, which featured a 40-foot-high fence that was just 233 feet away in left field. It was tailor-made for a hitter of McNulty’s power. In 1974, playing in his hometown for manager Bob Lemon, McNulty hit 55 home runs, drove in 135 runs, and scored the same number. His slash line was .329/.438/.690, for a season’s OPS of 1.128. The following year, through 40 games, McNulty was again on pace for a similar performance with the Solons, when he accepted an offer of roughly $70,000 to play the remainder of the season in Japan. He played his final 64 professional ball games with the Tokyo Lotte Orions in the Japan Pacific League, and then called it a career. In 11 minor-league seasons he’d hit 237 home runs.

With his baseball career over, McNulty returned to Sacramento and started to work. With a background in tools (while playing, he had invested in a hardware store in Sacramento), McNulty took a job with a chainsaw company and later became a salesman for a tool manufacturer, a position he still held in 2014.

Also, during his brief stay in Tacoma with the Cubs, McNulty met Sue Isekite; in 2014 they celebrated their 35th wedding anniversary. As of 2014 the couple resided in Eatonville, Washington; McNulty had two daughters and six grandchildren. Sue’s father, Floyd “Lefty” Isekite, was a minor-league pitcher who won 61 games pitching on the West Coast. Their fathers’ shared profession, McNulty said, was coincidental to the couple’s meeting.

McNulty left one final thought on the outcome of his career: “If I had to tell a manager about me if I was still playing, I would say what I am is consistent. I won’t get hurt. I’ll be there every day. But it’s going to average out over time. Be patient. But they don’t do that in the big leagues; they want you to produce right away. I just think I needed the right guy to have a little patience. It is what it is.”

Last revised: April 1, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

The author expresses his sincerest appreciation to Bill McNulty for phone interviews on October 10 and November 22, 2013, as well as subsequent email exchanges. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are drawn from those interviews.

Rose, George, One Hit Wonders: Baseball Stories (Lincoln: iUniverse, 2004).

(Galley proof) O’Connor, Alan, Gold On the Diamond: Sacramento’s Great Baseball Players 1886 to 1976 (Sacramento: Big Tomato Press, 2007).

The Sporting News

McNulty player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 The Sporting News, January 17, 1970.

2 The Sporting News, August 21, 1971.

10 The Sporting News, June 3, 1972.

12 The Sporting News, August 31, 1974.

Full Name

William Francis McNulty

Born

August 29, 1946 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.