Tony La Russa

In a sport where tradition reigns and change may be viewed as heresy, Tony La Russa was considered an insurgent within the ranks of major league managers. Especially with regard to relief pitching, he experimented with innovative strategies, some of which have become standard practice. His most notable contribution was his role in the development of the one-inning closer, which became the norm throughout baseball.

In a sport where tradition reigns and change may be viewed as heresy, Tony La Russa was considered an insurgent within the ranks of major league managers. Especially with regard to relief pitching, he experimented with innovative strategies, some of which have become standard practice. His most notable contribution was his role in the development of the one-inning closer, which became the norm throughout baseball.

Yet, despite the managerial revisions he introduced, La Russa was not a rebellious upstart who delighted in flouting tradition. At heart he was a classic baseball “lifer” who was passionate about the game and respected its history. His motive for challenging the basic tenets of how baseball is played was simple; his competitive spirit compelled him to search for any edge that would help his team win.

And win he did. When La Russa’s 33-year career ended in 2011, he had won more games than all but Connie Mack and John McGraw. In the process he led his teams to six pennants and three World Series titles and was four times voted Manager of the Year, finishing second five other times. He is one of two managers to win World Series in both leagues, one of nine to win three or more World Series titles, and the only one to win one in three different decades. In 2006 he became the first major league manager to win multiple pennants in both leagues. In 2013, his first year of eligibility, La Russa was unanimously elected to the Hall of Fame by the Expansion Era Committee.

The second child of Anthony and Olivia (Cuervo) La Russa, Anthony La Russa Jr. was born in Tampa, Florida, on October 4, 1944. His paternal grandparents had emigrated from Sicily and his mother’s family was originally from Spain. The family lived in Ybor City, where La Russa’s parents had met when both were working in a cigar factory. When La Russa was in high school his father got a job driving a delivery truck for a dairy, prompting the family to move to West Tampa.

“Spanish was my first language,” said La Russa, whose mother spoke Spanish and his father both Spanish and Italian. “I had to learn English to go to school. I was raised in a Latin American, Italian American community with a bunch of people who really loved baseball.”1 La Russa has been enshrined in both the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame and the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame.

“My father was fanatic about baseball,” recalled La Russa. “He was a pretty good catcher but never played much because his father would require him to do chores. We never had a lot of extra money and he worked so hard, but he always gave me every opportunity to play because he didn’t want me to be frustrated like he was.”

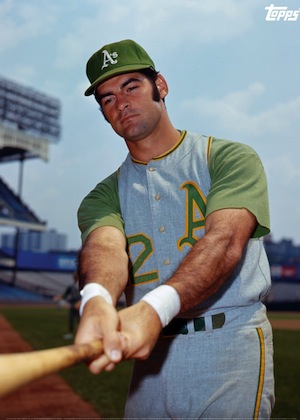

Like so many successful major league managers, Tony La Russa had an unremarkable career as a player. A standout in high school and American Legion baseball, he was sought by several major league clubs. When owner Charlie Finley offered the phenom not only a hefty bonus but also a new car and a promise to pay for a college education, La Russa signed with the Kansas City A’s in June 1962 upon graduating from Jefferson High School in Tampa.

Since La Russa was a “bonus baby,” the A’s were required to keep the 6-foot, 175-pound middle infielder on the major league roster for the entire 1963 season. However, a shoulder injury he had suffered while playing softball prior to the start of the season limited his playing time and performance; he appeared in only 34 games and hit .250.

The road back to the majors proved to be difficult. Hampered by a variety of injuries, he spent the next four years in the minors. He made it back to the big leagues in 1968, making the Opening Day roster of the transplanted Oakland A’s, but was sent back to the minors after appearing in five games. Between 1968 and 1973 he spent parts of five seasons with the A’s, Atlanta Braves and Chicago Cubs. In six major league seasons he compiled a .199 average with no home runs and seven RBIs in 132 games. He spent all or part of 15 seasons in the minors between 1962 and 1977, playing in 1,295 games and hitting .265.

In the 1962 offseason, La Russa first enrolled at the University of South Florida. Seven years later he received his degree in industrial management. By 1973 he realized his future as a ballplayer was limited and decided to pursue a different career path. “I always loved reading and problem solving and I had friends who were lawyers,” he said, “so that seemed like that would be a good thing to do.” Again taking courses during the offseason, he obtained his law degree from Florida State University in 1978 and was admitted to the Florida Bar in July 1980.

But even before he graduated from law school La Russa’s future course was changed when, in 1978, the Chicago White Sox offered him a job as the manager of their Double-A Knoxville Sox affiliate in the Southern League. When the White Sox named Larry Doby to replace Bob Lemon as manager in June, La Russa became Doby’s first base coach. The Sox offered him the same job in 1979, but he said he would prefer to manage in the minors. Prior to the 1979 season, La Russa, fluent in Spanish, managed the Estrellas Orientales club in the Dominican Winter League.

La Russa was managing the Iowa Oaks, Chicago’s Triple-A affiliate in the American Association, when, on August 2, 1979, he received a call from White Sox owner Bill Veeck telling him to report to Chicago as the new manager. At 34, La Russa became the youngest manager in the majors at the time. Impressed by La Russa’s intelligence and drive, Veeck and general manager Roland Hemond were convinced that La Russa was qualified for the job, but some viewed the hiring of the young and untested La Russa as a money-saving move. Fourteen games under .500 when La Russa took over, the Sox went 27-27 the remainder of the season.

With so little experience managing, La Russa was intent on learning all he could from others. “There were giants in the league then,” he said. “Guys like Sparky Anderson, Billy Martin, Chuck Tanner, Earl Weaver. All these guys answered a bunch of questions. Later you realize just how great their advice was.”

After suffering through 90 losses in La Russa’s first full season at the helm, the White Sox began an upward swing that culminated in a 99-63 record in 1983, winning the AL West by 20 games before losing the ALCS to Baltimore in four games. That was the year that La Russa hired pitching coach Dave Duncan, whom he had met in 1964 when both were playing in the Kansas City farm system. He would keep Duncan on his staff for the remainder of his managerial career. La Russa, whose job had been in jeopardy in mid-season, handily won the first of his three AL Manager of the Year Awards.

After the Sox third-place finish in 1985, GM Roland Hemond was replaced by their television broadcaster “Hawk” Harrelson, who was not enamored of La Russa. When the team got off to a 26-38 start in 1986 both La Russa and Duncan were fired. Owner Jerry Reinsdorf would later say that allowing La Russa to be fired was the biggest mistake he ever made. Two weeks later La Russa was hired by the Oakland A’s, inheriting a team mired in seventh place with a 31-52 record. Under their new manager the A’s went 45-34 and climbed to third place.

After the Sox third-place finish in 1985, GM Roland Hemond was replaced by their television broadcaster “Hawk” Harrelson, who was not enamored of La Russa. When the team got off to a 26-38 start in 1986 both La Russa and Duncan were fired. Owner Jerry Reinsdorf would later say that allowing La Russa to be fired was the biggest mistake he ever made. Two weeks later La Russa was hired by the Oakland A’s, inheriting a team mired in seventh place with a 31-52 record. Under their new manager the A’s went 45-34 and climbed to third place.

La Russa won his second AL Manager of the Year Award in 1988 when the A’s won the first of three consecutive pennants. In the bottom of the ninth inning of the World Series opener, the heavily-favored A’s led the Dodgers 4-3. With one on and two outs, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda sent a limping Kirk Gibson up to face A’s closer Dennis Eckersley, who had led the AL with 45 saves. With the count 3-2, Gibson hit a back-door slider into the right field stands to win the game, prompting CBS radio announcer Jack Buck to exclaim, “I don’t believe what I just saw!” The Dodgers went on to win the Series in five games, giving La Russa one of his most bitter defeats.

The A’s were not to be denied in 1989. They took the division title and won the pennant in five games over the Toronto Blue Jays. Then, in an earthquake-interrupted World Series, they swept the San Francisco Giants to give the 44-year-old La Russa his first World Series title. The A’s again easily won the division title in 1990, then swept the Red Sox in the ALCS. But their bid for a second straight World Series title fell short when they in turn were swept by the Cincinnati Reds.

After slumping to a fourth-place finish in 1991, the A’s quickly rebounded in 1992 to win their fourth division title in five years before losing to Toronto in the divisional series. It had been a particularly challenging season for La Russa, who had to deal with numerous injuries (56 different trios played in the outfield), a middle-of-the-pack offense with a lone .300 hitter, and disciplinary issues with slugger Jose Canseco, who was traded away at the end of August. But typical of La Russa’s teams, the A’s remained focused and found a way to grind through the season. La Russa’s balancing act earned him his third Manager of the Year Award.

By 1993, the A’s were no longer dominant; they lost 94 games and fell into last place. Two more losing seasons convinced La Russa that, after nine-plus years with three pennants and a World Series win, it was time to move on. Once again he was not unemployed for long; on October 23, 1995, he began what would be a 16-year stay with the St. Louis Cardinals. His move to the National League would give him a greater opportunity to indulge his penchant for strategical maneuvering.

The Cardinals, who had finished 19 games under .500 in 1995, won the NL Central title in their first season under La Russa. They swept San Diego to win the Division Series before losing the NLCS to Atlanta after winning three of the first four games. Then, between 2000 and 2006 they won five division titles. After leading the team to a NL Central Division title in 2002, La Russa won his fourth Manager of the Year Award, his first in the NL.

In 2004 La Russa made it back to the World Series for the first time since 1990 when the Cardinals, who won 105 games in the regular season–the most by any team he managed– defeated Houston to win the NLCS. But just as in 1990, La Russa’s squad was swept in the World Series as the Red Sox convincingly ended their 86-year title drought.

After losing the NLCS to Houston in 2005, the Cardinals finished first in the NL Central Division in 2006 despite an unimpressive 83-78 record. They went on to beat San Diego in the Division Series, then won the NLCS in seven games by defeating the favored New York Mets. Facing the Detroit Tigers, who had won 97 games, the Cardinals were clear underdogs. But after splitting the first two games, they won the next three to give La Russa his second World Series title. The Cardinals’ regular-season record was the worst ever for a World Series champion.

Five months after that triumphant moment a non-baseball incident generated embarrassing publicity. In the early morning of March 22, 2007, after having dinner with some friends, La Russa was arrested in Jupiter, Florida, on suspicion of driving under the influence when police found him asleep at the wheel of his running SUV, his foot on the brake. In November, as part of a plea agreement, La Russa was put on a six-month probation, fined, ordered to attend DUI classes and to perform community service. In a statement issued at that time, La Russa said: “I accept full responsibility for my conduct and assure everyone that I have learned a very valuable lesson and that this will never occur again.”2

For many, La Russa’s greatest achievement as a manager occurred in 2011, when the Cardinals came from 10½ games out of a playoff spot in late August to edge Atlanta for a wild-card berth on the last day of the season. Then, after being tabbed as the underdog in each of three postseason series, they provided their manager with his third and final World Series title in dramatic fashion. With Texas holding a 3-2 lead in the series, in Game Six the Cardinals were down to their last strike in both the bottom of the eighth and ninth but rallied twice to tie the game. They won it in the eleventh on a home run by David Freese, then wrapped up the title with a 6-2 win in Game Seven.

The Cardinals’ never-say-die season, so characteristic of La Russa’s teams, proved to be a fitting climax to his career. Three days after the Series ended, the 67-year-old manager announced his retirement. In his 16 years with St. Louis, he won more games than any other Cardinals manager, finished first in the division seven times and won three pennants and two World Series. His 2,728 career wins were third all-time, surpassed only by Connie Mack’s 3,731 and John McGraw’s 2,763; only he and Mack have managed in at least 5,000 games.

As devoted as he was to baseball, La Russa stayed in the game only as long as he felt the fire in his belly. When asked in 2008 what kept him motivated after all those years and all those wins, his answer made it clear that, for all the anxiety and frustration his job could bring, it’s what he was born to do. “As long as I get excited, I figure this is what I should be doing,” he said. “The key is, you’ve got a responsibility and an opportunity to put people in the right places and try to win games. If the fire keeps burning, I’m going to do it. If it doesn’t, it would be cheating, and I don’t want to cheat.” By October 2011 the fire had died out.

La Russa paid a price for his passionate commitment to baseball. In February 1965 the 20-year-old La Russa married Luzette Sarcone. The couple had two daughters, Andrea and Averie. But his devotion to his work kept La Russa away from his family for much of the year and in August 1973 the marriage ended in divorce. In Buzz Bissinger’s 2005 book, Three Nights in August, La Russa expressed regret for having chosen to dedicate so much time to his job: “I have huge regrets about it because I could have done just as well in my job with less significant time spent apart.”3

After his divorce became official, La Russa married Elaine Coker in December 1973. They have two daughters, Bianca and Devon. In 1991 he and his wife co-founded Tony La Russa’s Animal Rescue Foundation (ARF). Located in a 38,000 square-foot facility in Walnut Creek, California, ARF finds homes for abandoned dogs and cats, promotes the cause of animal rescue, and administers outreach programs designed to strengthen the bond between humans and animals.

Since his retirement, La Russa has devoted more time to ARF and other philanthropical endeavors. He also continued to be involved with baseball, working as a special assistant to the commissioner and serving on the three-member committee that formulated the expanded replay system approved by MLB owners in January 2014. In May 2012 the Cardinals retired his number 10, and in January 2014 La Russa was named as one of the inaugural members of the newly-established Cardinals Hall of Fame. The next month he was elected to the (San Francisco) Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame. In May 2014 he was appointed the Chief Baseball Officer of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

What distinguished La Russa as a manager was not just his record but the day-to-day intensity he brought to the game throughout his long career. He was, to put it mildly, detail oriented; his game preparation was meticulous to the point of obsession. In a game that requires equilibrium to survive the grind of a 162-game season, La Russa never let up. Dennis Eckersley was quoted as saying, “I never played for anybody who was as wired from pitch to pitch.”4 During a game, La Russa would stand at the bottom of the dugout steps near the bat rack, sternly scouring the field for one more move that could make the difference between winning and losing.

In his constant search for a competitive edge, La Russa did not hesitate to experiment, regardless of the response by media or fans. He tried batting the pitcher in the eighth spot in the lineup and in 1993 he briefly questioned the traditional role of the starting pitcher by using three pitchers in a game, each limited to three innings. As others would later, he employed specialty relievers in late innings to take advantage of situational match-ups. Though he credited Dave Duncan, La Russa is generally acknowledged as having defined the current closer role by using A’s reliever Dennis Eckersley almost exclusively in the ninth inning to protect a lead. Baseball analyst Bill James called this “the most important smart move of a manager in the 1980s.”5

Regardless of his achievements as an innovator, it was La Russa’s ability to get the most out of his players and mold them into a cohesive unit that made him one of the most successful managers in history. Although he utilized statistical analysis before it became the rage, La Russa understood the limits of a quantitative approach. He also needed to know a player’s mental makeup, what was in his heart and guts. No less important than statistics were desire, work ethic, and a commitment to the notion that winning mattered more than personal achievements. That approach required that La Russa know his players’ personalities, that he communicate with them and, when necessary. offer moral support.

He referred to his relationship with his players as personalization. In One Last Strike, his memoir of the 2011 season, La Russa wrote: “For years, what we’d always done as a coaching staff was to personalize our relationships with the players. Our goal was to create an environment where the ballplayer looked forward to coming to work and knew that a bunch of people were trying to put him and his teammates in the best position to win. . . . I had, contrary to the La Russa mystique, great relationships with the great majority of my players, good relationships with the rest, except for the few who were disgruntled with me or my leadership style.”6

Like all managers, La Russa was not always loved by everyone on his roster. But one of his dominant traits was fierce loyalty to his players. If he was convinced that an opposing pitcher had thrown at one of his men intentionally he would not hesitate to order a pitcher to retaliate. Perhaps his most defiant act of loyalty occurred in October 2009 when he hired Mark McGwire, long suspected of having used steroids as a player, as the Cardinals hitting coach. La Russa had consistently denied any knowledge of wrongdoing by McGwire, whom he managed for most of the slugger’s 16-year career. In January 2010, McGwire publicly admitted to having used steroids during his career, claiming they were a means of overcoming career-threatening injuries.

La Russa’s relations with the press were often tense and occasionally confrontational. Not one to suffer fools gladly, he had little patience with what he considered irrelevant or uninformed questions. Michael Bauman, national columnist with MLB.com who has covered the sport for 32 years, acknowledged that La Russa “bristled easily.” On the other hand, “if you asked an intelligent question you’d get an intelligent answer,” said Bauman. “There were times when he opened up and you could learn more baseball from him than anywhere else. The majority of the people who dealt with him came away with the impression he was a tremendous storehouse of knowledge and intelligence.”7

For all his success, La Russa was not without his detractors and was at times a polarizing figure. Inevitably, his style of managing, which was to play every game as if it were the seventh game of the World Series, did not endear him to everyone. Given his intensity, fierce competitiveness, occasionally volatile temperament, a willingness to retaliate when one of his players was thrown at, and a propensity for frequent late-inning pitching changes that lengthened the game, La Russa often frustrated opposing teams and their fans.

Regardless of the controversy he generated, Tony La Russa is acknowledged as one of the greatest managers in history. He left a legacy of strategical brilliance, innovation, and a passionate devotion to the game that ultimately earned him the respect of his peers and accolades from baseball analysts.

In Three Nights in August, author Buzz Bissinger, who was given access to La Russa throughout the 2003 season, does not refrain from portraying the less flattering elements of the manager’s complex personality. He describes La Russa as “intense, smoldering, a glowing object of glower. He barely smiled even when something wonderful happened, as if he were willing himself not to.” Nevertheless, Bissinger comes to this conclusion: “I came into this book as an admirer of La Russa. I leave with even more admiration. . . . La Russa represents, to my mind, the best that baseball offers.”8

Jim Leyland, La Russa’s third-base coach with the White Sox and later a rival manager, called him “the most creative manager I’ve ever managed against. He’ll do things other managers won’t. If his club isn’t hitting, he’s not afraid to try stuff to manufacture runs. I think he’s an offensive genius.”9

On the occasion of La Russa’s retirement, longtime rival manager Bobby Valentine said: “He was one of the most innovative managers of all time. He wasn’t always friendly, but you knew he was always ready to compete, and you respected and admired that about him. He goes out as one of the great ones of all time.”10

Roland Hemond, the White Sox GM who gave La Russa his first managerial job, is a three-time Executive of the Year and one of most respected figures in baseball. “Tony La Russa is one of the most brilliant managers that I ever encountered in my baseball career,” he said. “He saw things other people didn’t see. There were some managers who thought he was out of line with what he was trying to do, but later on they had to respect him because it was working. There’s no question he changed the way the game is played.”11

Published April 17, 2014

Sources

Bissinger, Buzz. Three Nights in August : Strategy, Heartbreak, and Joy Inside the Mind of a Manager. Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

James, Bill. The Bill James Guide to Managers from 1870 to Today. New York: Scribner, 1997.

La Russa, Tony, with Rick Hummel. One Last Strike: Fifty Years in Baseball, Ten and a Half Games Back, and One Final Championship Season. New York: William Morrow, 2012.

Rains, Rob. Tony La Russa: Man on a Mission. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009.

Will, George F. Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball. New York: Macmillan, 1990.

Associated Press. “As part of plea deal, La Russa gets probation, fine, community service,” ESPN, November 28, 2007.

Price, S. L. “Dark Times for a Baseball Man,” Sports Illustrated, June 4, 2007.

http://ancestry.com

http://baseball-reference.com

http://espn.go.com

http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/

New York Times

The Sporting News

Tony La Russa, personal interview with author, May 12, 2008.

Michael Bauman, personal interview with author, February 7, 2014.

Roland Hemond, telephone interview with author, February 15, 2014.

Notes

1 Tony La Russa, interview with author, May 12, 2008. Unless otherwise noted, all La Russa quotations are from this source.

2 Associated Press, “As part of plea deal, La Russa gets probation, fine, community service,” ESPN, November 28, 2007.

3 Buzz Bissinger, Three Nights in August : Strategy, Heartbreak, and Joy Inside the Mind of a Manager (Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 101.

4 Rob Rains, Tony La Russa: Man on a Mission (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 142.

5 Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Managers from 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1997), 259.

6 La Russa with Rick Hummel. One Last Strike: Fifty Years in Baseball, Ten and a Half Games Back, and One Final Championship Season (New York: William Morrow, 2012), 8, 103.

7 Michael Bauman, personal interview with author, February 7, 2104.

8 Bissinger, Three Nights in August, 1, xiv.

9 S.L. Price, “Dark Times for a Baseball Man,” Sports Illustrated, June 4, 2007

10 New York Times, October 31, 2011.

11 Roland Hemond, interview with author, February 15, 2014.

Full Name

Anthony La Russa Jr.

Born

October 4, 1944 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.