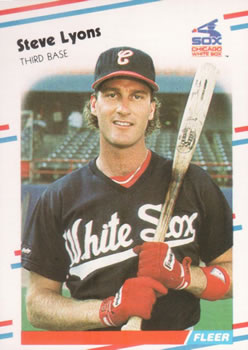

Steve Lyons

Steve Lyons was a utility player who spent nine years in the major leagues, including four stints with the Boston Red Sox; a left-handed hitter, he batted .252. But while that number might not seem impressive, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

Steve Lyons was a utility player who spent nine years in the major leagues, including four stints with the Boston Red Sox; a left-handed hitter, he batted .252. But while that number might not seem impressive, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

In fact, throughout his major-league career, Lyons frequently got people talking. Fans, sports reporters, and even his own managers never knew what to expect from Lyons, whose nickname was “Psycho.” He could be brash, emotional, and capable of boneheaded mistakes; or he could be a reliable clutch player whose versatility enabled him to step in at just about any position (during one exhibition game, he played all nine of them).

Lyons acknowledged that he was probably an overachiever: “I was never a great athlete or a great hitter,” he said. “I was never supposed to make the big leagues.”1 But he did, and during the nine seasons that he played for the Red Sox, Chicago White Sox, Atlanta Braves, and Montreal Expos, there were a number of memorable moments.

Stephen John Lyons was born on June 3, 1960, in Tacoma, Washington. He was strongly influenced by his father, Richard, who had been a three-sport star athlete (Class of 1953) at Hudson (Massachusetts) High School.2 Richard did not play college ball, but he never lost his love of sports, especially baseball. After relocating to the West Coast while in the US Army, Richard Lyons coached Little League; he also continued to follow the team he loved as a boy, the Boston Red Sox. “We would always watch the Red Sox [on television] when they were on the Game of the Week,” Steve recalled. His father’s favorite player was Carl Yastrzemski, while Steve’s was Fred Lynn.3

Steve’s interest in baseball developed early. He told a college newspaper reporter that he’d dreamed of a big-league career since he was 5.4 Like his father, he played several sports: When he attended Marist High School in Eugene, Oregon, he became known for basketball. But when he transferred to Beaverton High School for his senior year, he turned his focus to baseball, playing the outfield and distinguishing himself as a fielder. Although his batting average in his senior year was only .239, his enthusiasm and how hard he played the game earned him some attention. So did the trouble he had controlling his emotions: He would sometimes throw his helmet or bat in frustration when a call didn’t go his way.5

Despite the low batting average, at least one area coach saw Lyons’ potential and he was able to get a partial athletic scholarship to Oregon State University in Corvallis. He majored in business administration, and when not in the classroom, he was winning praise for his skill on the diamond, especially as a fielder for the Oregon State Beavers: He won two Gold Gloves, one in 1979 as an outfielder, and the other in 1980 as a third baseman. He also played some games at shortstop, and did well there too. But Lyons’ hitting skills needed improvement: his average hovered around the .250 range throughout his three years at Oregon State. His coach, Jack Riley, believed that the 6-foot-3 utility player had “all the tools” to become a success, noting his skill at fielding and running the bases. But Riley also noted the flaw in Lyons’ hitting. Pitchers had quickly learned that he couldn’t hit a breaking ball. His coach predicted a bright future for Lyons if he worked hard, but said he would first have to “mature mentally and learn how to hit.”6

Lyons did show some flashes of hitting ability. He played summer ball in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1980; as the shortstop for the Dodge City Athletics,7 he hit .377, with 20 home runs.8 Despite his low batting average for his college team, that success in summer ball got Lyons noticed. When the 1981 amateur draft took place, he was chosen by the Red Sox in the first round, as the 19th overall pick. The Boston newspapers described Lyons as someone with “above average speed, and a very fiery and intense approach to the game.”9 Reporters immediately noticed that he was very talkative (and quotable), and he seemed confident in his own ability. As soon as he signed his contract, he decided to drop out of college to pursue his dream of playing pro ball,10 and his first stop was at Class-A Winston-Salem, in the Carolina League. Lyons made a good first impression: He alternated between playing shortstop and the outfield, impressing Buddy Hunter, his manager, with his fielding. He also started off well at the plate, with 9 hits in his first 20 at-bats.11 But by season’s end, his average was similar to what it had been in college: In 64 games, he hit .242.

In 1982 Lyons was assigned to Double-A Bristol (Connecticut) of the Eastern League, where he mainly played outfield. While he stole 35 bases, he struck out 119 times and batted .243. In 1983 he was back in Double-A, playing the outfield for New Britain (Bristol’s successor). The team decided to try the versatile Lyons at third base. He played 87 games at third, along with 47 in the outfield. He even pitched in three games, and in one of them, he was the winning pitcher. And he continued to be a force on the basepaths, stealing 47 bases. But although he struck out far fewer times than the previous year, his average was just .246. On the other hand, Lyons did have some noteworthy moments while playing for New Britain. One of them involved his teammate, pitcher Roger Clemens, who made headlines by striking out 15 as New Britain defeated the Reading Phillies, 11-3. Lyons made headlines of his own, going 4-for-5, scoring four of his team’s runs, and stealing five bases.12 Boston sportswriters who watched Lyons play believed his batting average didn’t tell the whole story. One noted that even when not getting hits, he knew how to get on base, having walked 77 times, and because of all the positions he played and his speed and fielding ability, he was named New Britain’s MVP that year.13

In 1984 Lyons was promoted to Triple-A, spending the season with Pawtucket as the third baseman. It turned out to be an amazing year for the PawSox. The team was not expected to do much, but at year’s end not only were the PawSox in first place, they then won the International League championship in dramatic come-from-behind fashion.14 Lyons was a major contributor, and this time not just with his speed or his fielding ability. In the first half of the season he was one of Pawtucket’s best hitters, with big games like one against Rochester when he hit two homers and drove in six runs. 15 And even though his average tailed off during the second half, he still finished the season at .268. He was named to the International League’s final all-star team, the only member of the PawSox to win that honor.16

By spring training of 1985, baseball writers were wondering what the Red Sox planned to do with Lyons. He was praised for his work ethic and his desire to improve, but he still had problems hitting the curveball.17 He spent many hours working with Red Sox hitting coach Walt Hriniak, who believed Lyons had major-league talent. Hriniak advised the young man to be more patient, saying Lyons was “a hyper, aggressive kid who naturally jumps at everything. … He’s got to learn to wait on the ball.” But Hriniak had no doubt Lyons would become an asset to the Red Sox, even if he never became a power hitter. “[Steve] is someone you want on base. You want him to get as many hits and walks as he can because … when he gets on the bases, he makes things happen.”18 Hriniak’s tutelage seemed to help: By late March, Lyons was hitting .342 and finally showing the potential to handle major-league pitching.19

But although Hriniak and others defended Lyons, pointing out that not every successful major leaguer had put up big numbers in the minors, there was one other problem facing him: There seemed to be no place for him in the regular lineup. Third base was not the answer, since the Red Sox had Wade Boggs at that position, and the team needed his bat in the lineup. The other positions also seemed set, and Lyons’ best chance for making the team seemed to be as a utility player. Manager John McNamara believed that would be the right decision.20 In early April Lyons got the good news that he had made the team, even though he was not likely to play every day.

Lyons’ first major-league appearance was uneventful. He came in as a pinch-runner in a game against the Chicago White Sox on April 15. It would not be until five days later that he played in the field and got his first at-bat, and that was due to a knee injury that center fielder Tony Armas suffered. Lyons came in late in the game; in his first at-bat, he walked and then stole second, went to third on an error, and slid home safely when White Sox catcher Carlton Fisk failed to block the plate. The Red Sox went on to win, 12-8, thanks in large part to Marty Barrett’s first career grand slam. But Lyons’ speed and hustle did not go unnoticed. Peter Gammons wrote that Lyons “showed why it’s important he’s here instead of Pawtucket. … No one else on this team could have come in and created that sort of run.”21

But as versatile as Lyons was, that didn’t guarantee regular playing time. There was occasional pinch-hitting or pinch-running, but it wasn’t until May 27 that he got his first start, once again as a result of an injury to Tony Armas, who had sprained his wrist. Steve made the most of that opportunity, hitting two home runs and driving in four runs in a 9-2 win over the Minnesota Twins.22 But he was well aware that as soon as Armas was feeling healthy again, it would be back to the bench for him. Meanwhile, he was winning over Red Sox fans, who loved his aggressive and enthusiastic style of play. It even earned him the nickname “Psycho,” referring to his at times eccentric behavior, and his willingness to call attention to himself. “Maybe I go overboard sometimes … but I have so much fun playing the game,” he told a Boston reporter. “I’m the kind of player who … entertains people.”23

As it turned out, that would be a mixed blessing. While fans loved to watch Lyons, there were rumors that John McNamara, his manager, felt the rookie was too much of a showboat, once referring to him as “my self-proclaimed star”; but when questioned by the press, both Lyons and McNamara denied there was any problem.24 (Lyons later acknowledged that McNamara was tough on him, perhaps because he was one of the few rookies on the team. “He wanted to make an example out of me.”25) Several teammates, notably Rich Gedman and Bill Buckner, tried to help and mentor Lyons as he adjusted to the major leagues.26 Meanwhile, the fact that Tony Armas had not fully recovered and Lyons was playing well kept him in the lineup for more than two months.

After Armas returned to the lineup in August, Lyons went back to occasionally pinch-hitting, and waiting for his next opportunity. But if the rumors of friction between Lyons and McNamara hadn’t been true before, Lyons managed to get on his manager’s bad side with a baserunning blunder against the Twins in late August. Lyons was on second and Dwight Evans was at bat. Without waiting for permission, Lyons tried to steal third; Evans struck out, and Lyons was easily thrown out, ending the inning in a very close game. McNamara was furious, and it would not be the last time the two would clash.27

On the other hand, even with occasional errors in the field or displays of poor judgment, Lyons had become a fan favorite. Despite not playing regularly (he appeared in 133 games), he hit .264, with 5 home runs and 30 RBIs. And although he mostly played center field, he showed his versatility by playing some innings at third, short, right field, and left field. After the season the Boston Baseball Writers Association named him the Red Sox Rookie of the Year,28 and he was also given the Tenth Player Award by Boston’s WSBK-TV.29

During spring training in 1986, Lyons was excited to capitalize on what he felt he had achieved in his rookie year. He played an exhibition game at second base, adding another position to his repertoire.30 The always quotable Lyons told a reporter that “I’m most comfortable [playing] in the outfield, but I like the infield better. It suits my personality because there’s more people to talk to.”31 Meanwhile, there were signs that Lyons might get more playing time. Tony Armas spent much of April struggling at the plate. As the month ended, Lyons finally found himself back in the regular lineup. But once again he got on his manager’s bad side: For one thing, Lyons was in a slump of his own, swinging at bad pitches, and going 0-for-22 before finally getting a hit. For another, in a game against the Oakland A’s, he ignored a hit-and-run sign, and also got thrown out of the game for arguing a third-strike call. McNamara was very vocal about how upset he was with Lyons’ inability to stay focused and control his emotions.32

Sportswriters had often suggested that Lyons was not a good fit for the Red Sox. He was a nonconformist, someone who had his own unique style.33 That could have been ignored had he not also made careless mistakes, some of which cost his team a win. In early June against Milwaukee, Lyons tried to steal third with two out in the ninth inning and the tying runs on base (and, no, his manager had not given him permission to go). He was thrown out, ending the Sox rally. McNamara said it was the “stupidest [expletive] thing” he had ever seen, and also said he was tired of Lyons making stupid moves that hurt the team. McNamara announced that Lyons would be benched.34 As one writer remarked, Lyons had made an amazing transformation, and not in a good way: He had gone from being a bright young prospect to being a permanent resident of his manager’s doghouse.35 In late June the 26-year-old Lyons was traded to the Chicago White Sox for 41-year-old pitcher Tom Seaver.

Lyons joined his new team eager to play every day and determined not to be known for his mistakes. But with the White Sox, he struggled at the plate, and had few extra-base hits; in less than a month, he found himself back on the bench, frustrated at his missed opportunity.36 While manager Jim Fregosi did not openly criticize Lyons, there were rumors that he had never wanted Lyons on the team.37 At one point Fregosi hinted that he was not impressed with Lyons’ playing skills. When a reporter asked what Lyons’s strong points were, Fregosi replied, “He gives good TV interviews.”38 By mid-August the White Sox had optioned him to Triple-A Buffalo; Lyons wasn’t recalled till early September, when major-league rosters expanded. But his average remained low. He hit .203 in the 42 games he played for Chicago. Combined with the .250 he had hit before being traded, he finished the year batting .227.

In 1987 Lyons again alternated between the White Sox and the minor leagues. He began the season by being sent to the Pacific Coast League to play for the Hawaii Islanders, a decision he was bitterly unhappy about. But as luck would have it, he was recalled several days later when Chicago outfielder Harold Baines was injured.39 He was sent down again in May. In all, he played 47 games for Hawaii. With the White Sox, he played 76 games, and he finally showed some improvement at the plate. In fact, in another disappointing season for Chicago (fifth again in the AL West, this time with a 77-85 record), Lyons was one of the bright spots. He was platooned against right-handed pitchers and despite not playing regularly, he hit .280 and got some clutch hits later in the season. With the 1986 White Sox, Lyons had mainly played in the outfield, but in 1987 he was playing a majority of games at third base.

But at the end of the season, manager Jim Fregosi was still trying to decide how best to utilize Lyons. The White Sox were grooming Kenny Williams to be their everyday third baseman, and Lyons was on the verge of once again being the odd man out.40 Fregosi suggested that Lyons learn to be a catcher, so he went to the Instructional League to learn the position, even though he expressed some doubt about whether he was cut out for it.41 Fregosi wanted to give Lyons some time behind the plate during spring training, but there was also a plan to showcase his versatility in an unusual way. Several days before an April 1, 1988, exhibition contest against Cincinnati, Fregosi told the media that Lyons would attempt to play every position in the game. While two major-league players (Bert Campaneris of the Oakland A’s in 1965 and César Tovar of the Minnesota Twins in 1968) had already done it, this attempt would be unique, as Fregosi explained: “Lyons is going to do it in order of positions on the scorecard, one through nine. He’ll start as a pitcher, and finish as the right fielder. Don’t think that’s ever been done before.”42 But we will never know whether this was said as an April Fool’s Day joke, or if Lyons would actually have accomplished it. The game was rained out.

During the 1988 season, Lyons got into 146 games (the most he’d played in a major-league season). He hit .269, with 5 homers and 45 RBIs; he also got the most hits he had ever gotten – 127. However, he had a surprisingly poor year in the field. Normally reliable, Lyons took over at third base in July, but he made 25 errors in 128 games. Overall, he led the American League with a total of 29 errors. (The other four came when he was playing other positions.) But Lyons wasn’t alone. During 1988, the White Sox had the worst defense in the AL, committing 152 errors in 159 games.43

The White Sox had a new manager in 1989, Jeff Torborg. Lyons wanted to make a good impression, so he got his normally long hair cut to conform to Torborg’s dress code.44 But it was on the field that Lyons hoped to impress, and he seemed to get along with his new manager. He even told reporters he was having fun playing again.45 Lyons ended up batting .264 for the White Sox, with 2 homers and 50 RBIs. He also turned his fielding troubles around somewhat: Playing nearly every position except pitcher, he finished the season with a total of 15 errors, not as good as he wanted, but certainly better than he did in 1988.

But if there was a year when Lyons lived up to his nickname of “Psycho,” it was in 1990. On July 16, against Detroit, he slid into first base, beating out the throw in a close play. The front of his uniform was covered with dirt, and there was also dirt inside his uniform. And that was the problem. Lyons dusted off the front of his uniform, but then, on live TV, as shocked viewers (and equally shocked fans in the stands) watched, he pulled down his pants to shake out some of the dirt. I just kind of got my business done right out there on the field and then … uh-oh, after three or four seconds, I realized I wasn’t wearing any pants so I yanked them right back up as fast as I could.”46 But it was too late. The jokes and snide comments began almost instantly, as did offers to pose for Playgirl magazine.

There were other noteworthy moments for him in 1990, not all of them as outrageous. He finally achieved a goal that he nearly reached in 1988: He played all nine positions in one game. It was on April 23, 1990, during an exhibition game known as the Windy City Classic, between the White Sox and the Cubs at Wrigley Field. The White Sox won, 6-5, as Lyons gave the ultimate demonstration of his versatility.47 (Since it was an exhibition game, it didn’t go into the major-league record books, but it was still quite an accomplishment.)

Lyons also made his major-league debut as a pitcher, the one position he had not yet played in a regular-season game. On June 16, 1990, he came in during a blowout game against Oakland. He pitched two innings in Chicago’s 12-3 loss. While not making the world forget Cy Young, he also didn’t do a terrible job. He gave up one run, two hits, and four walks. More importantly, he gave the other relief pitchers some needed rest.48 Still, despite a season with some unique moments, he played in only 94 games and batted .192. And by now, he had gotten his manager upset by complaining about his lack of playing time.49 Lyons was fairly certain he would not be in Chicago’s plans for 1991.50

The White Sox did invite Lyons back to spring training, but on April 13, they put him on waivers. What happened next was a surprise. After Red Sox general manager Lou Gorman first denied that the team had any interest in him,51 on April 18 the Red Sox signed Lyons as a free agent. It turned out that Red Sox manager Joe Morgan was one of Lyons’ biggest supporters. As Morgan explained, “What I like is his attitude about the game and the fact he can play anywhere. … He’s played all nine positions and I know he could play seven of them [not catcher or pitcher] pretty decently.”52 The fans were delighted to have Lyons back, although several of the players were not as enthusiastic. (They believed the club should have kept utility player Randy Kutcher, who was waived to make room for Lyons.53) Joe Morgan’s assessment of Lyons’ abilities proved accurate. During the 1991 season, he played every position for the Red Sox except catcher. He even took another turn as a pitcher, hurling the ninth inning in a 14-1 loss to the Twins and giving up two hits and no runs.54) And while Lyons’ batting average was higher than in 1990, he ended the year at .241. Several months later, when Lyons and the Red Sox management were unable to agree on his salary, the team let him go, ending what some reporters had called the “Psycho II” era.55

But Lyons’ major-league career was far from over. The Atlanta Braves signed him in early January 1992, and things seemed to be looking up. But he didn’t hit, going 1-for-14. The Braves quickly soured on their new acquisition and wanted to demote him to Triple-A. When he refused, the team released him. He was briefly picked up by the Montreal Expos, but didn’t hit well for them either, going only 3-for-13. And then … in late June, he was purchased by the Boston Red Sox, becoming the first player in the team’s history to be hired three times.56 After only six plate appearances, Lyons was sent to Triple-A Pawtucket, with the promise that he would be brought back in September. He had now played for four teams (Atlanta, Montreal, Boston, and Pawtucket), and the season wasn’t even halfway over. “It’s been a disastrous season, really,” Lyons said, “because I want to play and I haven’t been able to play all that much.” Lyons played 37 games for the PawSox in 1992, batting .259; with Boston, he played a total of 21 games, hitting .250. But his hitting totals for the Red Sox were deceptive: He was able to get some clutch hits on a number of occasions.57 However, when the Red Sox cleaned house at the end of their disastrous 1992 season, Lyons once again was released.

He briefly latched on with the Chicago Cubs in February 1993, but was released at the end of March. In May, the Red Sox announced they had signed Lyons yet again, this time to a minor-league contract. And by mid-June, when the Red Sox needed someone to fill in at second base, Lyons was called up. A month later, he was on his way back to Pawtucket, where once again he tried to make the best of the situation. He even told reporters he was working on a book about his experiences.58 (That book, PSYCHOanalysis, was released in 1995, published by Sports Publishing LLC, with a foreword by Stephen King.59 Lyons wrote a second book, The Psycho 100: Baseball’s Most Outrageous Moments,” in 2009, published by Triumph Books.)

In 1993 Lyons hit just .213 for Pawtucket, and .130 for Boston. At the end of the season he filed for free agency, but was not picked up by anyone. It was not entirely surprising. “I knew [by then] my skills were declining,” he said.60 The former first-round draft pick, who had at one time been so highly touted, decided to retire as a player. Looking back on his nine years in the majors, Lyons said, “I know I was an average major-league player. I got tabbed as a utility player right away and didn’t play all the time, but I do believe I lived up to my potential. I never hit for average, but I was always an impact player.”61

Lyons returned to something he had begun doing in 1985: sportscasting. He had first done baseball reports for an AM station, WSRO in Marlboro, Massachusetts.62 Now he was able to get hired as an analyst by ESPN and ESPN2, and beginning in 1996, he spent 11 years working for Fox Sports, and also did color commentary for the Los Angeles Dodgers games. He was fired from Fox in October 2006, after being accused of making a racially insensitive remark about Lou Piniella.63 And when Lyons’ nine-year association with the Dodgers ended in 2013, he was hired by New England Sports Network (NESN) in 2014 as a Red Sox studio analyst.64 Although at times he has been criticized as too talkative, or has said something politically incorrect, Lyons has carved out a successful niche as a sports broadcaster. And he didn’t find the transition from player to announcer difficult: “I talk about the game better than I played it,” he said. 65

One of the best assessments of Steve Lyons’ career comes from the foreword that Stephen King wrote for PSYCHOanalysis: “Lyons epitomizes what may be best in sport: a player who is not great, but who was at times elevated (crazed, some might believe) by his love of the game and his determination to play it well.”66

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Notes

1 Personal interview with Steve Lyons, conducted by telephone, July 24, 2015.

2 Peter Gammons, “Snow Puts Rangers, White Sox in Hole,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1982: 52.

3 Lyons interview.

4 Larry Peterson, “Lyons, Hunsinger Turn to Pros,” (Oregon State) Daily Barometer, June 30, 1981: 15.

5 Dwight Jaynes. “Red Sox Rookie’s Tale of Trail to Big Time like Fable Come True,” The Oregonian (Portland), June 4, 1985: D1-2

6 Larry Peterson.

7 “A’s Take Low Scoring Twin Bill,” Dodge City (Kansas) Daily Globe, July 3, 1980: 10.

8 “Bosox Tab Beavers’ Lyons,” The Oregonian, June 9, 1981: D3.

9 Steve Harris, “On the Road With the Sox,” Boston Herald-American, June 9, 1981: B3.

10 “Bosox Tab Beavers’ Lyons.”

11 Peter Gammons, “Winston-Salem Has Some Winners,” Boston Globe, July 4, 1981: 24.

12 “Clemens Fans 15,” Boston Herald, August 25, 1983: 53.

13 Michael Madden. “No Chance of a Lifetime,” Boston Globe, March 11, 1984: 52.

14 Joe Gordon, “The Man Behind the PawSox,” Boston Herald, September 23, 1984: 59.

15 “Lyons Belts 2 HRs in PawSox Romp,” Boston Herald, April 23, 1984: 54.

16 Joe Giulotti, “Clemens to Miss Start,” Boston Herald, September 6, 1984: 70.

17 Bob Ryan, “Of Red Sox Third Basemen, Present and Future,” Boston Globe, August 5, 1984: 59.

18 Quoted by Peter Gammons in “Lyons a Bit Player with Star Potential,” Boston Globe, March 11, 1985: 34.

19 Tim Horgan, “The Lyons of Winter Haven a Real Smash,” Boston Herald, March 28, 1985: 77.

20 Peter Gammons, “Lyons Has Been a Tiger, Burning Bright,” Boston Globe August 2, 1985: 42.

21 Peter Gammons, “Lyons an Able Replacement after Armas Injures Knee,” Boston Globe, April 21, 1985: 50.

22 Ben Walker, “Rookie Lifts Red Sox Over Twins,” Centre (Pennsylvania) Daily Times, May 28, 1985: D-2.

23 Joe Gordon, “Lyons’ Act Big Hit at Fenway Park,” Boston Herald, June 4, 1985: 70.

24 Dwight Jaynes, “Red Sox Rookie’s Tale of Trail to Big Time Like Fable Come True,” The Oregonian, June 4, 1985: D1-D2.

25 Lyons interview.

26 Lyons interview.

27 Joe Gordon, “Smithson Silences Sox 1-0,” Boston Herald, August 25, 1985: 43.

28 “Sox Honor Lyons,” Boston Herald, November 17, 1985: 8.

29 Larry Whiteside, “Lyons Voted Tenth Player,” Boston Globe, September 23, 1985: 38.

30 Larry Whiteside, “Lyons Can’t Wait for Second Chance,” Boston Globe, March 23, 1986: 99.

31 Dan Shaughnessy, “Trade Should Bolster the Sagging Sox,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1986: 80.

32 Joe Giuliotti, “Rice Surprised by 2,000th Hit,” Boston Herald, May 11, 1986: 43.

33 Dan Shaughnessy, “Lyons on the Loose,” Boston Globe, July 29, 1986: 57.

34 Joe Giuliotti, “Lyons Benched for Ninth-Inning Gaffe,” Boston Herald, June 7, 1986: 68, 72.

35 George Kimball, “Hawk Lends Helping Hand,” Boston Herald, June 30, 1986: 59.

36 Gerry Finn, “Steve Lyons Still Sittin’, but It’s Not on Top of the World,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, August 5, 1986: 8.

37 Carrie Muskat, “(No) April Fooling,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, April 1, 1988: 1D.

38 Joe Giuliotti, “Baseball Notebook,” Boston Herald, August 24, 1986: 68.

39 Jeff Baker, “Few See Beavers Blast Hawaii,” The Oregonian, April 10, 1987: E1, E4.

40 Carrie Muskat, “Sox Catcher Lyons a Seedy Character,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, March 3, 1988: 4C.

41 Bob Verdi, “Sox Put Lyons in Odd Position,” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1988: C1.

42 Ibid.

43 Carrie Muskat, “Where the Cubs, Sox Stand in ’89,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, December 11, 1988: 1-2E. Lyons made one error at second base, one in center field, and two in right field.

44 Carrie Muskat, “Image Now Biggest Concern in Baseball,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, April 3, 1989: 3C.

45 Marvin Pave, A Good Break for Lyons, Boston Globe, July 22, 1989: 31.

46 Michael Madden, “Lyons’ Popularity is Peeking,” Boston Globe. August 1, 1990: 25.

47 “Baseball: White Sox Edge Cubs,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) Daily News, April 24, 1990: 2B.

48 Mark Curnutte, “Pitching Performance Not Significant to Lyons,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, June 18, 1990: 14.

49 “Lyons Surprised to Be Back,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, March 1, 1991: 2C.

50 Mike Shalin, “Greenie Effect Worries Sox,” Boston Herald, December 16, 1990: B21.

51 Mike Shalin, “Joe: Ump too Quick on Draw,” Boston Herald, April 15, 1991: 66.

52 Nick Cafardo, “Lyons Isn’t Any Tamer,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1991: 37.

53 Steve Fainaru, “Lyons Back With Boston, Kutcher Is Given His Release,” Boston Globe, April 19, 1991: 30.

54 Joe Giuliotti, “Psycho Bails as Sox Sink,” Boston Herald, July 22, 1991: 68.

55 Nick Cafardo, “Braves’ 2-Year Offer Guarantees Lyons’ Exit from Boston,” Boston Globe, January 9, 1992: 29.

56 Nick Cafardo, “Lyons returns – But What’s Next?” Boston Globe, June 30, 1992: 55.

57 Nick Cafardo, “Sox Clean House in Big Way,” Boston Globe, December 26, 1992: 34.

58 Nick Cafardo, “Lyons Up to His Old Tricks and Throws in New Stuff,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1993: 59.

59 Jim Greenidge, “Lyons Shares Some Laughs,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1995: 52.

60 Lyons interview.

61 Lyons interview.

62 Jim Baker, “Short Takes,” Boston Herald, February 9, 1986: 52.

63 Nick Cafardo and Gordon Edes, “Lyons Fired by Fox; Hispanic Remarks Called Insensitive,” Boston Globe, October 15, 2006: D7.

64 Chad Finn, “Dell is officially done at NESN,” Boston Globe, May 13, 2014: C8.

65 Lyons interview.

66 Steve Lyons, PSYCHOanalysis (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1995), xi.

Full Name

Stephen John Lyons

Born

June 3, 1960 at Tacoma, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.