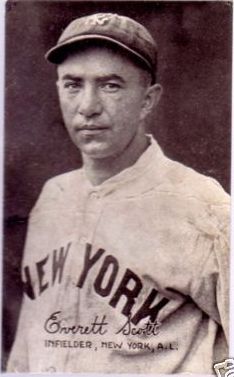

Everett Scott

Shortstop Lewis Everett “Deacon” Scott was the steady infield leader of championship Red Sox and Yankee teams of the 1910s and 1920s. Beginning June 20, 1916, and ending May 6, 1925, he played in 1,307 consecutive games, which was the major league record until Lou Gehrig and then Cal Ripken broke it. Not only was Scott an accomplished ballplayer, but he also wrote a children’s book and became a skilled bowler. Although he was never seriously considered for baseball’s Hall of Fame, Scott was considered to be the finest shortstop of his time.

Shortstop Lewis Everett “Deacon” Scott was the steady infield leader of championship Red Sox and Yankee teams of the 1910s and 1920s. Beginning June 20, 1916, and ending May 6, 1925, he played in 1,307 consecutive games, which was the major league record until Lou Gehrig and then Cal Ripken broke it. Not only was Scott an accomplished ballplayer, but he also wrote a children’s book and became a skilled bowler. Although he was never seriously considered for baseball’s Hall of Fame, Scott was considered to be the finest shortstop of his time.

Lewis Everett Scott was born on November 19, 1892, in Bluffton, Indiana. He graduated from Bluffton High School, where he was a pitcher, in 1909. His family moved to Auburn, Indiana, while Everett started his pro baseball career in 1909 in Kokomo of the Northern State of Indiana League. That same year, he went to Fairmont, West Virginia, of the Pennsylvania-West Virginia League; he played for both teams in 1910 but in reverse order. In 1911, he moved on to Youngstown (Ohio-Pennsylvania League).

While Scott was playing for the Youngstown Steelmen (now in the Central League) for a second year in 1912, the Boston Red Sox minority owner, Jimmy McAleer, a native of Youngstown, observed him on June 6, and, two days later, offered a contract for Scott to the Youngstown owner; the Boston Braves also made an offer, of $5,400. The Washington Senators were scouting Scott, too. The Senators determined that Scott’s body weight of around 120 pounds would not allow him “to keep up the strenuous pace demanded in the big show,” certainly ironic in light of Scott’s later consecutive games streak. [1] After marrying Gladys Watt, his childhood sweetheart, on August 20, 1912, Scott signed with the Red Sox on August 22. In the offseason he worked as an inspector in a piano factory.

In 1913, Scott was assigned to the American Association’s St. Paul Saints. Called “Scottie” by the St. Paul fans, he received rave reviews for his speed in the field, his throwing arm, and, most importantly, “baseball brains.” [2] His .269 average that year was virtually identical to that of his two previous seasons. On January 31, 1914, Scott signed a contract with the Red Sox for $2,500, despite having been offered $4,000 by the Federal League’s Indianapolis team. [3]

Scott, who batted and threw right-handed, arrived with a great advance buildup in Boston in 1914; even the great Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics was impressed by his fielding prowess after an early season game against the Red Sox. On Opening Day, April 14, he played his first big league game, succeeding the incumbent, Heinie Wagner. His rookie year .239 batting average was good for a shortstop during this era, and his fielding was good enough, too. He cut his errors almost in half in his second season with the Red Sox.

In 1915, Scott’s brother, Charles, a pitcher, was invited to spring training with the Red Sox, but did not make the club. During the season, the diminutive shortstop, at 5 feet 10 inches and 135 pounds, saw his batting average dip to .201, but his steady defense was one of the main reasons why the Red Sox advanced to the World Series, defeating the Philadelphia Phillies in five games. Scott had just one hit, a single, in 18 Series at-bats.

The 1916 Sox returned to the World Series once more and they defeated the Brooklyn Robins in five games. For the season, Scott had improved his batting average to .232, as well as being the American League leader in fielding average for shortstops. Wilbert Robinson of the Robins nicknamed him “Trolley Wire,” a tribute to his accurate throws from shortstop to first during the Series. Scott was 2-for-16 with one RBI in the 1916 Series.

After two world championships in his first three years, Scott felt he deserved more money and sent back the contract the Red Sox offered to him for the 1917 season, which (after the collapse of Federal League competition) had offered a slight decrease in salary. However, within a few days, Scott came to terms with the Red Sox and earned a substantial raise, from $3,000 to $4,500. [4] During the offseason, though, Scott’s wife, Gladys, spent time in a sanitarium and it was reported that when Scott reported to spring training, he appeared drawn. [5] He later left camp to be with his wife when she needed surgery. He nonetheless played a full 157 games in the regular season, hitting .241 in 528 at-bats as the Red Sox finished nine games behind the Chicago White Sox, the eventual World Series champion.

Beginning with an abridged spring training, the 1918 season was directly affected by World War I. Players were not able to get into game condition, resulting in many lame arms among pitchers. In addition, the Army’s provost marshal, General Enoch Crowder, issued a ”work or fight” order that required eligible men of draft age to enlist in the armed services or find work in war-related industries. Some 237 players left their teams during the season. However, neither Scott nor teammate Harry Hooper missed a league game all season and, by the time the World Series against the Chicago Cubs was played, the two players were the only position players left from Boston’s 1916 championship team.

During the shortened season, which ended on September 2, Scott continued his consistent play, making only 17 errors and, despite hitting only .221, contributed 26 sacrifice hits and struck out only 11 times. The World Series ended in a Red Sox victory in six games, with Scott contributing 26 assists in the field and turning three double plays. Before Game Five, the players on both teams briefly refused to take the field because of problems with the way the World Series money was to be allocated. [6] The dispute was resolved and the Red Sox had their fifth championship. After the season, Scott was honored in Spalding’s 1919 baseball record book as a baseball “Hall of Fame” member (this was before the official Baseball Hall of Fame was established), recognizing his achievements during the 1918 season. He had also surpassed previous longevity marks, established by Eddie Collins (470 games) and George Burns (459 games). On April 23, 1919, it was announced that Scott had signed a three-year contract with the Red Sox.

After five full seasons in the major leagues, Scott had established himself as a consistent and dependable, if not flashy, player. Although his batting average was usually low, he was considered to be a player whom a manager would like to have up at the plate in a difficult situation [7]. In the 1915 World Series, for instance, he bunted on a third strike, catching the Philadelphia infield flat-footed and advancing a runner who later scored a decisive run. [8] He showed an uncanny knack for playing batters correctly in the field and his throws from any part of the infield were accurate. [9] Entering the 1919 season, he had played 524 consecutive games, despite being afflicted by a recurring condition of boils, and assorted injuries. Covering his wounds with bandages, he was able to continue playing, although in considerable pain. [10]

Although the 1919 season was a disappointment for the Red Sox, Scott hit a career-high .278 and led all American League shortstops in fielding. But his wife was unhappy being away from him and alone with their child in Indiana, and it was reported that Scott requested a trade to a team closer to home, such as Chicago, Detroit, or St. Louis, after the season concluded. [11] Scott disputed the rumored trade possibility, attributing it to unreliable sources. [12]

The Red Sox began spring training in 1920 with a team in transition, held together by Scott, Hooper, and John “Stuffy” McInnis. Despite their efforts, the Boston club eventually finished 25 1/2 games behind the American League champion Cleveland Indians. Scott played in 154 games, amassing a career-high 210 total bases, with four home runs and 61 RBIs. During the season, he passed the 533 consecutive games mark of the Phillies’ Fred Luderus, hitting a rare home run in the process. On April 26 he broke the record of 577 consecutive games played set by George Pinkney of Brooklyn from 1885 to 1890, and played his 600th straight game on July 14. Throughout the season, his streak withstood a wrist injury caused by a pitched ball, and an ejection from a game in which he played 3 ½ innings.

In the offseason, Scott continued his conditioning program, preparing himself for the rigors of playing shortstop in an era when players regularly sharpened their spikes and were not afraid to use them to cut middle infielders when they slid into a base. To reduce injury, Scott wore padded shoes to protect his ankles from spike wounds.

Early in 1921 spring training, Scott suffered a charley horse injury that lingered throughout the spring training schedule. However, the injury did not stop his streak, which reached 700 on May 17, in a game during which he made a phenomenal force out by diving face first into second base. Stating a goal of attaining the 1,000 mark, he played in number 800 on September 2. Still esteemed by fans and press alike, Scott continued to be praised for his consistency in the field and at bat. It was strongly felt that his record for consecutive games was unbeatable. His 62 RBIs in 1921 were the most he’d driven in for the Red Sox.

Despite his fine play, trade rumors persisted during the offseason: first, a two-way deal between the Yankees and the Red Sox and then a three-way deal between the Yankees, Red Sox, and Tigers were rumored to be in the offing. Finally, a trade was announced in which the Yankees received Scott and pitchers Joe Bush and Sam Jones in exchange for shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh and pitchers Bill Piercy, Rip Collins, and Joe Quinn. In addition, in a separate deal, the Red Sox traded Stuffy McInnis to Cleveland, further raising suspicion that owner Harry Frazee was in the process of selling the club, and that perhaps there was money involved coming from the Yankees to the Red Sox in the Scott deal. [13] The local press in Boston denounced the deal as being strongly in favor of the Yankees, while the national press was mixed. In retrospect, it seems apparent that Frazee was systematically dismantling the Red Sox, sending them into a free fall that would put them out of serious pennant contention for a generation.

Scott’s reaction to the trade was that he would have preferred to stay in Boston, but, if he had to go anywhere, he was glad to go to New York, since he would be reunited with many of his old Red Sox teammates, such as Babe Ruth, Waite Hoyt, and Wally Schang. He felt that he had been treated well in Boston. [14]

During spring training in 1922, the Yankees announced that Babe Ruth would become the captain of the Yankees, replacing the traded Peckinpaugh. However, because of an incident the previous season, Ruth was suspended until May. It was suggested that perhaps Scott, having been the captain of his Red Sox team, might be appointed captain until Ruth’s return. It is easy to see why Scott would be considered for this honor, for beyond his stellar play on the field, he also was adept at many hobbies, including auction bridge, whist, poker, fishing, and bowling. Scott became the captain of the Yankees, serving in that role until he left the club in 1925.

Although Scott’s first game as a Yankee was a loss, his consecutive games streak continued. The great sportswriter Grantland Rice remarked: “After Everett Scott is dead we expect to see his ghost out there playing short through force of habit. No such shallow barrier as the grave will ever check the Deacon’s tireless pace.” [15]

After Scott played in his 900th consecutive game, the Washington Post referred to him as the “iron man” and also mentioned his ability as a “great money player”, citing his penchant for performing strong when much is at stake. [16] However, the streak almost came to an end on September 14 when, after visiting his home in Indiana, he caught a train to Chicago to meet up with his teammates there. The train blew out a cylinder head along the way, and Scott was forced to take a car, another train, and then a taxi to arrive at the ballpark late. He entered the game in the seventh inning, enough to count for a game to continue his string of 972 games. That year, Scott was again the American League’s leader in fielding at shortstop.

A highlight of the 1922 World Series between the Yankees and the New York Giants was the anticipated battle of the shortstops, with Scott being the better fielder, and the Giants’ Dave Bancroft being the better hitter during the regular season. At Series end, won in five games (one tie) by the Giants, the two shortstops had played to a virtual tie. But it was evident, especially to Scott, that he was unable to cover as much ground in the Series as he normally would. To Scott’s credit, he mentioned that he was getting older, but also said the Fenway Park infield which he manned for so many years was a slower track, allowing him to get to balls more easily than both the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium. [17]

When Yankee contracts went out to players for the 1923 season, the general consensus was that several star players would be asked to take a cut in salary. Scott’s salary remained the same and he promptly returned it signed. After a period of conditioning in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and spring training in New Orleans, Scott entered the season knowing that he needed only to play 14 games to reach his goal of 1,000 consecutive games. On April 13 in an exhibition against Brooklyn, though, he sprained his left ankle while falling over second base and it was feared that he had also torn his tendons. Because of his age and the nature of his injury, it was generally thought that he would miss at least the first game of the season. In fact, Yankee manager Miller Huggins said he anticipated that Scott would be sidelined for two or three weeks. However, after using crutches and wrapping his ankle in bandages, he was able to play on Opening Day, the first game ever played in Yankee Stadium. More than 74,000 fans were treated to a home run by Babe Ruth in a 4-1 win over the Red Sox. Scott was credited with the first assist at the new Stadium.

Scott persevered despite his injury and, on May 2, 1923, at Washington’s Griffith Stadium, he participated in his 1,000th consecutive game. To mark the occasion, he was presented with a solid gold medal in a pregame ceremony in which he was praised by Secretary of the Navy Edwin C. Denby as “the greatest ballplayer in point of service and achievement that ever trod the diamonds of America, the home of baseball.”[18] Despite his accomplishment, it was reported that, although Scott held the major league record, a minor leaguer named Perry Lipe had participated in 1,127 consecutive games.

As the season progressed, the whispers began that Scott was getting old and getting slower and that he was not doing the Yankees any favors by playing with nagging injuries. He began to make costly errors when he could not get to balls that he used to field with ease. On August 23, he ran his streak to 1,100 games and soon claimed the world’s record by playing in his 1,128th game, surpassing Lipe. In a rematch of the previous two years’ World Series, the Yankees finally won their first title, defeating the Giants, four games to two, with Scott getting a key hit and scoring a run in a five-run rally to win Game Six.

After the season, Scott considered retiring from baseball to enter business, hinting that he wanted to leave baseball with pride in his accomplishments. It was thought that manager Huggins might bench Scott for a couple of games at the start of the season in order help him improve his play over the course of the season; another consideration was to involve Scott in a trade. This possibility gained credence when the Yankees acquired Earle Combs in a trade to serve as an understudy. Despite all the talk, Scott signed a contract for the 1924 season, after spending the winter resting his legs by staying away from playing basketball. Clearly, though, Scott’s star in New York was fading.

By the beginning of the season, Huggins had backed away from benching Scott, saying that he might need a rest in July or August when the weather became hot. Scott played on, reaching 1,200 straight games on June 28.

At season’s end, the Yankees had finished two games behind the Washington Senators and Huggins strongly hinted that he needed a new shortstop for the following season. It was suggested that Scott had an “obsession” with his streak and by playing every day was not exercising common sense. For years, he had taken to wrapping his legs in bandages in order to compensate for various injuries. Scott performed well, however; his .250 average in 1924 was a notch above his .246 of the previous year , and his 64 RBIs a career high. His number of putouts and assists was significantly larger, and his fielding percentage improved.

Scott showed his bowling prowess during the offseason, participating in several tournaments. He also hoped to purchase a bowling establishment when he retired. Despite reports that he would not play on Opening Day because of a pulled muscle, Scott continued his streak. But criticism of his “obsession” continued, and, finally, on May 5, 1925, the streak ended when Paul “Pee Wee” Wanninger started in Scott’s place. At first, it was reported that Scott was “not feeling well”, but later it was reported that he had been sat down because of a shakeup in the Yankee lineup.

Scott was angered by the move, and returned to Indiana for a few days to consider his options. He insisted that he was not upset by the end of the streak, but rather that he had been playing better and expected to play. In an attempt to add humor to the end of the streak, writer James R. Harrison of the New York Times noted that it had been reported that Scott was benched by the same type of stomach ailment that had sidelined him the day before his streak began in 1916. Harrison joked, “If such is the case, the thing is getting chronic and Everett should see a doctor.” Critics also noted that Scott’s streak was aided by the fact that he had not played every inning of every game, sometimes playing only a small portion of a game. Regardless, Scott made only a few more appearances in a Yankee uniform, his last start coming in the second game of the May 30 doubleheader. Scott’s final 18 games with the Yankees saw him bat just .218. Two days later, on June 1, teammate Lou Gehrig began his own consecutive game streak that would eventually reach 2,130 games.

Scott’s streak broken, the impasse with the Yankees ended when Scott was finally claimed on waivers by the Washington Senators on June 17, 1925. Coincidentally, he initially played behind Roger Peckinpaugh, who had been involved in the trade with the Red Sox that sent Scott to the Yankees. After an injury to Peckinpaugh, he played well (hitting .272) in 33 games for the Senators, who went to the World Series but lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates, four games to three.

Scott’s desire to leave baseball increased, and his successful bowling and billiard establishment in Fort Wayne, Indiana, led him to consider retirement again. Nevertheless, Scott’s passion for baseball still burned and he was claimed on waivers by the Chicago White Sox from the Senators in March 1926, and appeared in 40 games for them. He then was claimed on waivers by the Cincinnati Reds from the White Sox on July 6 and appeared in four games.

The following season, 1927, Scott was signed by the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, for whom he played 109 games, hitting 11 home runs and driving in 69 runs before being unconditionally released on August 4. He signed with the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association eight days later, playing 33 games before being released on December 7.

In 1928, Scott signed with Reading (International League), playing in 131 games and batting .315, and returned to the team for the 1929 season, appearing in 62 games, before being released in July.

After baseball, Scott continued to manage bowling alleys and billiard parlors in Fort Wayne, as well as continuing to participate professionally in bowling tournaments, rolling 51 perfect games in his career. In 1928, a children’s book he wrote called Third Base Thatcher was published by Grosset and Dunlap as part of the Christy Mathewson series of books.

As a result of his streak, Scott was also uniquely qualified to comment on the consecutive games mark that was being established by Lou Gehrig of the New York Yankees. In a July 7, 1939 column written by Bob Considine, Scott, reflecting upon Gehrig’s streak, felt that Gehrig should have first broken the streak established by Scott by about a hundred games and then should have played about 125 games a year from that point on, thus prolonging his career.[19] In an ironic twist, it was Pee Wee Wanninger whom Gehrig pinch-hit for to begin his own streak, which eventually reached 2,130 games. Cal Ripken Jr. currently holds the all-time record of 2,632; he has held first place since September 7, 1995.

Everett Scott died on November 3, 1960, at Parkview Hospital in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He had been in poor health in the years prior to his death. He was survived by his wife, Gladys; a son known as Everett Jr.; a grandchild; two brothers; and a sister. Scott was buried in Bluffton’s Elm Grove Cemetery.

Notes

[1] Youngstown (Ohio) Vindicator – June 6 and July 31, 1912.

[2] Boston Daily Globe, August 8, 1913, p.6.

[3] New York Times. January 31, 1914, p. 9.

[4] Boston Daily Globe, February 22, 1917, p.4.

[5] Boston Daily Globe, March 11. 1917, p.14.

[6] Boston Daily Globe, September 11, 1918, p.1.

[7] Chicago Daily Tribune, January 12, 1919.

[8] New York Times, September 23, 1919, p.25.

[9] Tracthenberg, Leo, “The Durable Deacon.” Yankees Magazine, December 17, 1992, pp.38-41.

[10] Sebring, Blake, “Our Own Iron Man.” Fort Wayne News Sentinel (online), April 20, 2006.

[11] “Red Sox Will Lose Clever Shortstop.” Washington Post, October 20, 1919, p. 10.

[12] “Boston Club Suits Everett Scott.” Boston Daily Globe, October 29, 1919, p.9.

[13] New York Times. December 26,1921, p.21.

[14] Atlanta Constitution. January 8, 1922.

[15] Boston Daily Globe. May 12, 1922, p.18.

[16] Washington Post. June 25, 1922, p.44.

[17] Boston Daily Globe. January 1, 1923, p.6.

[18] Boston Daily Globe. May 3, 1923, p.12.

[19] Washington Post, July 7, 1939

Full Name

Lewis Everett Scott

Born

November 19, 1892 at Bluffton, IN (USA)

Died

November 2, 1960 at Fort Wayne, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.