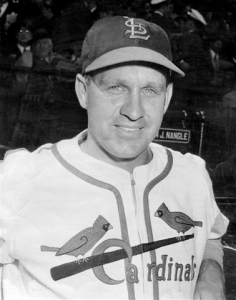

Enos Slaughter

Most great players have something similar during their careers: a dominant year, a key series in which they made their name — or a signature play. Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter’s even had a nickname. His “Mad Dash” in Game Seven of the 1946 World Series took place on the brightest of stages. It’s certainly one of the reasons why he was enshrined in Cooperstown in 1985. Yet there was much more. Over a 19-year big-league career, he posted a .300 batting average, with 2,383 hits. Had he not lost three prime years to World War II, he could have approached 3,000. The aggressive, constantly hustling outfielder was selected to play in ten All Star Games, eight straight with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1946 to 1953. “One of the greatest,” remarked Casey Stengel, later his manager with the New York Yankees. “He will do anything to beat you.”

Most great players have something similar during their careers: a dominant year, a key series in which they made their name — or a signature play. Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter’s even had a nickname. His “Mad Dash” in Game Seven of the 1946 World Series took place on the brightest of stages. It’s certainly one of the reasons why he was enshrined in Cooperstown in 1985. Yet there was much more. Over a 19-year big-league career, he posted a .300 batting average, with 2,383 hits. Had he not lost three prime years to World War II, he could have approached 3,000. The aggressive, constantly hustling outfielder was selected to play in ten All Star Games, eight straight with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1946 to 1953. “One of the greatest,” remarked Casey Stengel, later his manager with the New York Yankees. “He will do anything to beat you.”

Enos Bradsher Slaughter was born April 27, 1916, in Roxboro, North Carolina. He was the third of six children born to Zadok and Lonie Gentry Slaughter. Enos was raised on a 90-acre farm in the nearby community of Allensville that required him to work many chores. Whether it was milking four cows that developed strong hands and powerful wrists — or working in the fields on summer days that strengthened his back and arms — Slaughter was a physically fit young man. Enos and his four brothers (Daniel, Carlton, Hayward and Robert) took a keen interest in sports. The Slaughter boys gravitated towards baseball, each playing on the Person County team through the years.

Enos was a star at Roxboro High School in football and baseball, but passed up a scholarship to Guilford College in Greensboro. Ever since seeing the Durham Bulls play in the Piedmont League when he was a boy — the Slaughters took a horse and buggy to some of those games — he had seen baseball as his future. He decided to work in Durham and play semipro ball. The elder Slaughter was dismayed, but allowed his son to follow his dream. “If you can do what you want to often enough, you ought to be happy,” said Zadok.

Enos found work at a textile mill, splitting cloth as it came off the looms by day and playing on the mill’s semipro team at night. Durham Morning Herald sports editor Fred Haney wrote of young Slaughter’s fine play, recommending him in a letter to Oliver French, business manager of the St Louis Cardinals farm club in Greensboro.

Originally a second baseman, Slaughter was offered a 10-day tryout to latch on with the Cardinals organization. Former major leaguer Billy Southworth was running the camp for the Cardinals. Although Enos hit the ball well, Southworth noticed a flaw in Slaughter’s game. “Look kid,” said Southworth. “Do you realize that you are running flat-footed? Try running on your toes.” Within days, Slaughter said he was a good four steps faster getting down the line.

Eddie Dyer piloted the Columbus (Georgia) Red Birds of the South Atlantic League in 1936. He had some helpful advice for the young prospect. When the innings would change, Slaughter, who was playing in the outfield, would chug slowly to the dugout. When he passed first base, his lope became a slow walk. Dyer remarked to the youngster, “Listen, are you too tired to run all the way? If you are, I’ll get some help for you.” From that point on, Slaughter hit the top step of the dugout running, whether he was entering or exiting the playing field.

The next year, Burt Shotton managed the Class AA Columbus (Ohio) team of the American Association. He took one look at Slaughter with his florid face, his straw-colored hair and his tight-fitting clothes and bestowed the name “Country” on Enos. It stuck with him for the rest of his life. After hitting .382 for the Redbirds, Shotton pressed St. Louis general manager Branch Rickey to promote him to the big leagues. The Cards had another hot outfield prospect on that Columbus team named Johnny Rizzo. Rizzo hit .358, but it was Slaughter whom the shrewd Rickey kept, trading Rizzo to Pittsburgh. Rizzo’s last season in the majors was 1942. Enos found the general manger to be a tough negotiator at contract time, commenting that the frugal Rickey “went to the vault to change a nickel.”

Slaughter broke in with St. Louis in 1938. The era of the Gas House Gang may have been winding down, but their roughhouse style of play suited Slaughter. The Cardinal teams of the early 1930s had a lust for the game of baseball, and they played it to the hilt. Cardinal skipper Frankie Frisch called Enos the “the most hustling so-and-so in the game today.” And Frisch was the manager for only the outfielder’s rookie year. Max Lanier was a teammate of Slaughter’s at AA Columbus. He also made his big league debut in 1938 and remembered that Frisch intimidated the younger players. “He was the toughest manager I ever played for, but he knew his baseball,” said Lanier. “Us kids were afraid to talk back. He had Enos Slaughter scared to death in right field. Enos couldn’t pick up a ground ball. Frisch would be in the clubhouse, and the game would be over, and he’d walk up and down the aisle and say ‘Ballplayers, my ass.’”

Slaughter batted .276 his rookie year, his lowest average in the 13 years he suited up for the Cardinals. He matured into a potent offensive force, giving the Cards a good mix of veterans (Slaughter, Mort Cooper, and Terry Moore) who blended well with the younger players (Marty Marion, Stan Musial, Whitey Kurowski). Under the guidance of Southworth, St. Louis won three consecutive National League pennants beginning in 1942. Slaughter led the league in hits (188), batting average (.318) and triples (19). He was named to the Sporting News All Star team for his fine season.

When the sun set on July 31, 1942, Brooklyn had a firm grasp on first place. The Dodgers were 8½ games ahead of the Redbirds. But the Cards put together an incredible streak, posting a combined 46-12 record in August and September to knock off the Dodgers.

Their opponent in the Fall Classic was the New York Yankees. The kings of the American League flexed their muscles early, winning the first game by a score of 7-4. In Game Two, the Cardinals clung to a 4-3 lead when Bill Dickey led off the inning with a single. Tuck Stainback was inserted as a pinch-runner for Dickey, but when Buddy Hassett singled to right field, Slaughter nailed Stainback by ten feet as he tried to take third base. The Cardinals finished off the Yankees to even the series. In Game Three, Slaughter robbed Yankee slugger Charlie Keller of a home run by plucking the ball from the air at the outfield wall to keep it from going out of the park. Slaughter was not the hitting star of the Series (5 for 19 with a homer), but his solid defense showed a well-rounded game.

After the conclusion of the series, Slaughter enlisted in the United States Air Force. For the next three years, he was a member of a different team. He was assigned to the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center, for Enos wanted to be a pilot. After the discovery that he was color-blind, he was offered the job of bombardier, but he declined. Instead he was given the rank of sergeant, and became a physical education instructor, in charge of 200 troops. In the last year of his enlistment, Slaughter toured the South Pacific with Joe Gordon, Howie Pollet, Birdie Tebbetts, and other major leaguers as they played exhibition games at Tinian, Saipan, Guam and Iwo Jima. He was discharged from the service on March 1, 1946.

Slaughter returned to the Cardinals, hustling and giving 100% to the team as always. He led the league in RBIs with 130 in 1946, helping to lead St. Louis to the pennant, their fourth in five years. Chicago Cubs general manager Jim Gallagher observed of Enos, “That big-rumped baboon goes into the Army, drinks beer for three years and comes out running faster than before.”

After St. Louis advanced to the World Series by beating Brooklyn in a playoff, they faced the Boston Red Sox. The championship was decided by the famed “Mad Dash.” Not only was the series deadlocked at three games, the score was tied at three. Boston had scored two runs in the top of the eighth inning to tie the score, courtesy of a two-run double off the wall in right-center by Dominic DiMaggio. But the Red Sox paid a huge price as DiMaggio, thinking triple all the way, hobbled into second base with a pulled hamstring.

Boston manager Joe Cronin replaced the “Little Professor” with Leon Culberson in center field. Although Cronin did not have much choice, the move proved costly. Slaughter led off the bottom of the frame with a single to center off Boston reliever Bob Klinger. The next two batters were retired when Harry Walker planted himself in the batter’s box. “The Hat” promptly doubled to the gap between left and center field. Culberson and Ted Williams gave chase. Slaughter was off on the pitch and sped around the bags. Culberson threw the ball to shortstop Johnny Pesky, all the while he and Williams were yelling “Home, home, home.” Slaughter had blown through the stop sign put up by third base coach Mike Gonzalez, and never let up on his goal of scoring the tie-breaking run. He accomplished it, sliding home safely as catcher Roy Partee took Pesky’s weak throw several feet up the third-base line.

There were many observations about how Slaughter scored from first base. Culberson was not shaded enough over to left field with Walker, who was noted for spraying the ball to all fields, at bat. Culberson bobbled the ball briefly. Pesky dropped his hands just for an instant after he retrieved the ball from center field. Cronin said that it took a quick second for Pesky’s eyes to adjust to the shadows surrounding home plate in the late afternoon sun at Sportsman’s Park. Did two other infielders, Bobby Doerr and Pinky Higgins, yell too much to Pesky — or not at all, as Slaughter thought? Pesky had his own explanation, although it might be considered a bit mythical. “He must have sprung wings,” said John. “I would have had to have a cannon for an arm.”

To Slaughter, the play was nothing out of the ordinary. That was how he played the game, all out, all the time. However, in Game Five, he was hit on the right elbow by a pitch from Boston’s Joe Dobson. The pain was excruciating. “I wouldn’t give nobody the satisfaction of knowin’ I was hurt,” said Enos. In an act of boldness, he then stole second base. On the train ride to St. Louis, the team doctor put bags of ice on Slaughter’s elbow, but told the slugger that he would be sidelined for the rest of the series. But he was defiant once more, telling the doctor “I ain’t gonna do it. The fellers need me. No matter what you say, I’m playin.’” Apparently there was nothing wrong with his guile or his legs.

Slaughter contributed more than his legs to the 1946 series. Although he hit .320, it was his rifle arm that made people take notice. He led the league in assists from his right field position with 23. In Game Four at Fenway Park, the Cardinals were in command with a 7-1 lead. With one out and the bases loaded, Boston catcher Hal Wagner lifted a fly ball to right. Slaughter gathered it in and threw out Rudy York at the plate for the double play. “What the hell, don’t they run in the American League?’ asked Country.

In 1991, HBO released a documentary called When it Was a Game, which featured home movies taken by fans and players as well as commentary from players, coaches and writers about how baseball was played from the 1930s through the mid-1950s. One of the commentaries was from Slaughter, who talked about how it was not unusual to get brushed back or hit by a pitcher back in his day. The Cardinals and Dodgers were fierce rivals, and it was not uncommon, according to Slaughter, to have at least three hit batters — otherwise it was not a Cards-Dodgers game. Slaughter remarked that he would always keep it in the back of his mind if a pitcher knocked him down or nailed him in the back with a pitch. His retribution would be to take their legs out from under them the next time they tried to cover first base. It did not bother him at all to do so and he had no regrets. That was the way the game was played, and to Enos, the right way.

Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers for the 1947 season, integrating baseball. The concept brought much bitterness and contempt from some of Robinson’s teammates, various members of opposing teams, and in the press. Many teams planned to strike in May of 1947, in a show of solidarity against the entry of Robinson into professional baseball. An admonition by Commissioner Ford Frick, as well as a promise that any such action would lead to a player’s suspension from baseball, squelched any ideas of a revolt. In 1990, a book was published, entitled The Ballplayers. In Slaughter’s entry, the author made the following assertion:

“Slaughter, who was a North Carolina tobacco farmer, and fellow Southerner Terry Moore tried to persuade their Cardinal teammates to go on strike in May 1947 to protest Jackie Robinson’s admittance to the National League.”

Moore and Slaughter strenuously objected to these statements, going as far as to hire lawyers to set the record straight. Although at the time their involvement in such a move may have been rumors and speculation, here it was written as fact. Even though it was many years after their playing days, the suggestion of being a racist was an unwelcome label.

The Redbirds faced off against the Dodgers on August 20, 1947 at Ebbets Field, in another battle of first- and second-place teams. With the score tied at two in the top of the 11th inning, Stan Musial was on first base. Slaughter hit a Hugh Casey offering to first base, which was fielded by Jackie Robinson, who looked to second, thought better of it, and ran to first base to record the out. As Robinson turned toward the field of play to ensure that Musial did not take off for third base, Slaughter was coming hard down the line and spiked Robinson’s right ankle, causing Robinson to clutch his ankle in tremendous pain. He was able to remain in the game after receiving treatment.

Slaughter’s action was viewed more as dirty than aggressive. Robinson was rightly upset, but commented little about the incident other than to say, “All I know is that I had my foot on the inside of the bag. I gave Slaughter plenty of room.” Slaughter maintained that he had never spiked another player in his life. Unfortunately for Slaughter, because of this incident and rumors of a boycott against Robinson, there were racial undertones directed at him. He spent much of his life defending himself against such allegations. St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg supported Enos in this effort, saying, “The stigma is unfair.”

Yet again, the Cardinals fought the Dodgers for the pennant in 1949, holding a 1½ game lead on September 25. But they closed the season losing four out of five games to the sixth-place Pirates and the last-place Cubs, while the Dodgers won three out of five to claim the title. The Sporting News named Slaughter National League Player of the Year. He was third in the league with a .336 batting average, fourth in the league with an on base percentage of .418, and tied Musial for the lead in triples with 13.

The Cardinals slipped back to the rest of the pack in the National League, as Brooklyn and New York dominated the league until the late 1950s. The organization realized that it would need to reinvent itself in order to be competitive. August A. Busch Jr. laid out the team’s outlook by stating, “We set out on a program of building from the ground up — a long-range program of reorganization and development through the entire Cardinal system. The Cardinals are trying to build a young ball club.”

Two days before the 1954 season began, to make room for Wally Moon, Slaughter was traded to the Yankees for outfielder Bill Virdon, pitcher Mel Wright, and minor league outfielder Emil Tellinger. Country took the news hard, openly crying at the thought of leaving the only family he had been associated with in professional baseball. Cards manager Eddie Stanky summed up the move by saying, “A player like Slaughter just can’t stand sitting on the bench and, while I am not trying to put myself on a pedestal by comparing myself with him, I couldn’t stand it, either.”

Slaughter started only 22 games in right field, and was also employed as a pinch-hitter. He missed over a month of the season after crashing into the outfield wall at Yankee Stadium, fracturing his left wrist in three places. The Bombers traded him the next season, along with pitcher Johnny Sain, to the Kansas City Athletics for pitcher Sonny Dixon. The A’s had relocated to Kansas City from Philadelphia following the 1954 season. Owner Arnold Johnson owned Yankee Stadium, as well as being a friend and business associate of Yankee owners Dan Topping and Del Webb. This association prompted much speculation — and at times open outcry — about deals between the two clubs. Between 1955 and 1959, the two teams made 16 trades, involving 61 players, making it appear that Kansas City was no more than a minor league affiliate to New York.

Despite starting in just 77 games in right field for the Athletics, Slaughter was voted the Most Popular Player by the fans, edging out first baseman Vic Power. He rebounded to hit .322, but in only 267 plate appearances. Enos was presented with a new Chrysler Imperial for his efforts. During the last home series against Chicago, Slaughter showed that he still had some of his old swagger. In a pinch-hit performance, he tapped a grounder to first base. As pitcher Sandy Consuegra moved over to cover the bag, he dropped the ball after being sent sprawling into right field by Country. It didn’t matter that Kansas City was already winning 8-1. Slaughter’s trademark hard play earned much applause from the crowd.

Much in the way that a parent club recalls a minor-league player who is performing at a high level, New York reacquired Slaughter from Kansas City for the waiver price on August 25, 1956. “It’s great to go back to the Yankees, and I sure think I can help the club,” he said. To make room for Slaughter on the roster, the Yankees released the popular Phil Rizzuto the same day.

Slaughter played sparingly for the Yankees over the next four seasons. But the Old War Horse (a nickname given to him by St. Louis Post-Dispatch Columnist Bob Broeg) still made his mark. He hit a key three-run homer off Roger Craig in Game Three of the 1956 World Series that powered the Yankees to a 5-3 victory. He contributed in any way that Casey Stengel needed, as the Yankees won three straight pennants and two world championships between 1956 and 1958.

The Yankees released Enos near the end of the 1959 campaign, and he finished the season in Milwaukee. Although his major-league career then ended, he then managed for two seasons in the minor leagues: with Triple-A Houston in 1960 and Class B Raleigh in 1961. He even played in 40 and 42 games those two years, largely as a pinch hitter. After that, though, the managing jobs dried up — a source of discontent, as his autobiography later showed.

At the age of 45, Slaughter then retired to his 240-acre farm near Roxboro, where he harvested tobacco, watermelon, and assorted vegetables. He traveled the nation, making personal appearances and later, many baseball card shows. He supported many local institutions in his native Person County, including the history museum and Piedmont Community College.

In 1971, Slaughter was named the baseball coach of Duke University in Durham. He succeeded Tom Butters, the former Pirates reliever who became head fundraiser and later director of athletics at Duke. Butters said in 2007, “I have too many memories of Enos to count! He was a character, in the nicest sense of the word.” In seven lean seasons, Slaughter’s record was 68-120, as the Blue Devils were above .500 only in his first year. He coached one future big-leaguer, John Poff.

In 1985, with support from Bob Broeg and Monte Irvin of the Veterans Committee, Slaughter was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Another great Cardinal outfielder, Lou Brock, was in his commencement class. “My life is complete,” said Enos. “I feel great. Regardless of what uniform I wore, I gave 100% for whatever team I played.”

Slaughter put out his autobiography — called Country Hardball — in 1991. Five years later, the St. Louis Cardinals retired his number 9. He is one of nine Cardinal players to be so honored.

Enos Slaughter passed away on August 12, 2002 at the Duke University Medical Center. He was 86. He had been suffering from non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and had begun chemotherapy and radiation treatment in late May. He had also had surgery to repair his colon and perforated ulcers in his stomach (the operations were not related to his lymphoma). He was survived by four daughters; Gaye, Patricia, Sharon and Rhonda. He had been married and divorced five times.

At the funeral in Allensville Methodist Church, many former teammates paid their last respects, lamenting their loss — but rejoicing in their memories of Country. “Enos and I are in the Hall of Fame together,” said Brock. “History finds us together. That is one thing that binds me to him. And, I’ll tell you this, the name of Enos Slaughter will be spoken for generations to come. Players like Enos and Stan Musial really helped me to see what being a Cardinal meant. He’s been my friend for a long time.”

In 1963, a rookie second baseman for the Cincinnati Reds recalled a memory from his childhood. “I used to watch the Reds games on television,” said Pete Rose. “One day, the Reds were playing the Cardinals. Slaughter drew a walk and ran hard to first base. I decided right then and there that was what I was going to do as long as I played ball.” The original “Charlie Hustle” did not hail from the Queen City. He was actually from Roxboro, North Carolina.

Sources

Peterson, Richard. The St. Louis Baseball Reader. University of Missouri Press, 2006.

Golenbock, Peter. Dynasty: New York Yankees 1949-1964. Prentice Hall, 1975.

Golenbock, Peter. The Spirit of St. Louis. Harper Collins, 2000.

Eig, Jonathan. Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. Simon & Schuster. 2007.

Peterson, John E. The Kansas City Athletics: A Baseball History. McFarland and Company, 2003.

Katz, Jeff. The Kansas City A’s & Wrong Half of the Yankees. Maple Street Press, 2007.

Mileur, Jerome M. High Flying Birds: The 1942 St. Louis Cardinals. University of Missouri Press, 2009.

Shatzkin, Mike (editor). The Ballplayers. Arbor House Publishing, 1990.

Slaughter, Enos with Kevin Reid. Country Hardball. Tudor Publishers (Greensboro, North Carolina), 1991.

Boatwright, Phyliss. Person County Past: Tales from the Central Piedmont. The History Press (Charleston, South Carolina), 2006.

Costello, Rory. Tom Butters biography, SABR BioProject.

“Baseball Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter Dies at Age 86” (http://www.dukehealth.org/health_library/news/5706)

Fetatherston Al. “Hall of Famer, 86, Dies at Duke.” Durham Herald-Sun, August 12, 2002.

2011 Duke Baseball Media Guide, www.goduke.com

Eisenbath, Mike. “Enos Slaughter: He Set the Standard for Hustle.” Baseball Digest, September 1992.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Players Archive File

1930 United States Census

http://www.baseball-reference.com/

http://www.baseballinwartime.com/

http://www.baseballlibrary.com/homepage/

http://stlouis.cardinals.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=stl&tcid=mm_cle_sitelist

Full Name

Enos Bradsher Slaughter

Born

April 27, 1916 at Roxboro, NC (US)

Died

August 12, 2002 at Durham, NC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.