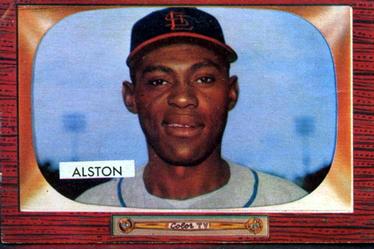

Tom Alston

Tom Alston tried to hit big-league pitching while hearing voices, battling chronic fatigue, and carrying the weight of being a racial pioneer in a Jim Crow city.

Tom Alston tried to hit big-league pitching while hearing voices, battling chronic fatigue, and carrying the weight of being a racial pioneer in a Jim Crow city.

Alston, the first African-American player for the St. Louis Cardinals, spent most of his life in torment and poverty. He never escaped the grip of mental illness that ended his baseball career.

Besides the pressure to make it in the majors and to be “a credit to his race,” Alston faced the added burden of being the most expensive black player ever. The Cardinals paid the Pacific Coast League’s San Diego Padres more than $100,000, plus four players, for his contract.

His debut in 1954 came seven years after Jackie Robinson’s. That year, for the first time, a majority of the 16 major league teams had black players, although those players made up less than 6 percent of the rosters. They were no longer an experiment, but not yet commonplace.

The Cardinals were latecomers to integration. Front-office executive Bing Devine said the owner from 1947 to 1953, Fred Saigh, refused to sign black players. There was a widespread belief that St. Louis was, in many ways, a Southern city. In the mid-1950s many of its stores and restaurants refused to serve black customers. The Cardinals, with baseball’s largest radio network blanketing the Midwest and South, had cultivated white Southern fans. Their ballpark was the last in the majors to abolish segregated seating.

When Anheuser-Busch bought the franchise in 1953, August A. Busch Jr. noticed the absence of black faces and ordered his baseball staff to find some. Busch was no civil rights crusader; he was an equal opportunity capitalist who wanted to sell his beer to everyone regardless of race, creed, or color. The Cardinals hired Negro League veteran Quincy Trouppe as a scout and signed more than a dozen African-Americans in the first year of the Busch regime. The talent search eventually led to Alston.

Thomas Edison Alston was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, on January 31, 1926, one of five sons and two daughters of Shube and Anna Alston. His mother, a maid, brought home newspapers from the houses she cleaned, and young Tom became an avid reader of the sports pages. He had a paper route delivering a black newspaper that taught him about Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and other stars of the Negro Leagues.

Growing up in the black community of Goshen, he first played with a broomstick bat and a tennis ball. The segregated Dudley High School had no baseball team. After high school Alston joined the Navy in 1944, where he played on his first organized teams. He returned home to attend North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, and began playing for a black traveling team known as the Goshen (later Greensboro) Red Wings.

Alston joined another barnstorming team, the Jacksonville, Florida, Eagles, managed by former Negro Leagues pitching star Chet Brewer. In 1951 Alston received his Bachelor of Science degree and went with Brewer and several other Eagles to play in Indian Head, Saskatchewan. The Indian Head Rockets dominated western Canada’s baseball leagues and won several Canadian tournaments.

Brewer took Alston with him to organized professional baseball in 1952, with the Porterville, California, club in the Class C Southwestern International League. Alston hit .353 and slammed 12 home runs in 54 games, but the franchise and the league were limping toward collapse. San Diego bought his contract for $100.

In his Pacific Coast League debut in June, Alston chased a foul ball and fell headfirst into the dugout, knocking himself cold. At 6-foot-5 and around 200 pounds, he appeared to be all arms and legs and huge feet, but he showed outstanding speed and a slick glove at first base. Hitting was another matter; PCL pitchers held the gangling left-handed batter to a .244 average.

The next spring Alston became the personal project of Lefty O’Doul, the Padres manager and a celebrated hitting guru. “I really believe Tom has a chance of hitting 50 homers this year,” O’Doul gushed. “He has improved so much I can hardly believe it.” O’Doul said Alston was already a big league-quality fielder and the fastest man on the team.1 The Padres thought they had a valuable prospect, but their phenom was 27 years old. No, you’re not, the club told him. You’re 22. At that age he would be more attractive to major league buyers.

O’Doul looked like a prophet early in the 1953 season. Alston hit 13 home runs in his first 50 games and was batting close to .300. The San Diego Union’s Jack Murphy hailed him as a $200,000 prospect, while describing him in stereotypical terms as “a happy-hearted Negro with the build of a basketball goon and a getalong borrowed from Stepin Fetchit.”2

Veteran pitchers soon learned that they could get Alston out with high fastballs, and he didn’t hit left-handers at all. After a midsummer slump, Alston made adjustments and began to hit again, though without his early power. He managed only 10 more homers in the final two-thirds of the season. He finished at .297/.353/.446 with 101 RBIs in 180 games.

Alston was exhausted at the end of the long PCL season, but he joined a teammate in winter ball in Mexico. Called back to San Diego in January 1954, he learned that the Cardinals had bought his contract. “I can’t believe it,” he said. “Me on the same team with Stan Musial?”3

Many followers of the Coast League couldn’t believe the six-figure price tag. In only his second professional season, Alston had had a good, but not great, year; scaling his 180-game totals back to a 154-game major league schedule puts him at 20 homers and 87 RBIs. The consensus was that St. Louis had been fleeced.

The Cardinals made their acquisition of Alston a media event. The team rented a suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel in Hollywood, and Busch himself came out to sign the contract. Sportswriters sipped Budweiser with caviar on the side. “The only blacks in the room were me and the valet who served the beer,” Alston recalled.4

“We took the viewpoint from the very beginning that we wanted the very best players we could get,” Busch said, “that there would be no barriers in terms of race, religion or anything of that sort.”5 He said the Cardinals had scouted the young player extensively and conducted a background check on his personal habits. “Our scouts, manager Eddie Stanky, and everyone on our staff are high on him. Now that I have met Alston in person and visited with him today, I’m more satisfied than ever that the Cardinals and all St. Louis will be proud of him.”6

Alston returned home a hero. His alma mater, North Carolina A&T, honored him at an assembly, and a sportswriter drove him to Roxboro to meet the Cardinals’ veteran star Enos Slaughter. Slaughter greeted his new teammate with a smile and a handshake, advising him to leave the game on the field and not worry too much.

When spring training began, manager Stanky said he planned to platoon Alston with the incumbent first baseman, Steve Bilko. A ponderous right-handed hitter, Bilko had slugged 21 home runs in 1953, but led the majors with 125 strikeouts while batting .251.

Although the $100,000 man was obviously getting special handling, Alston didn’t remember any open resentment. “The Cardinals had the rap of being bigoted,” he said decades later. “I didn’t experience anything real bad. None of the players were friendly to me, but they weren’t rude.”7 He recognized where he stood: “I thought I had a fair spring, but I think they were giving me a chance because I was Mr. Busch’s pet project.”8

Alston was in the Opening Day lineup even though the Cubs started left-hander Paul Minner. The rookie went 0-for-4 and dropped a popup. The next day Bilko stepped in against Braves lefty Warren Spahn and also went 0-for-4. The rest of Alston’s first week could hardly have gone better. His first two hits were home runs on consecutive days, one a three-run pinch-hit clout that gave the Cardinals their first victory of the season.

He began playing every day. By the end of April he was batting only .211, but the fix was in. The Cardinals sold Bilko to the Cubs. With his replacement no longer lurking in the dugout, Alston went on a tear. He hit .442 in the next 11 games after Bilko left.

Then National League pitchers discovered his weakness for high inside fastballs. Alston batted .181 in June with no home runs. “I’d wake up some nights and hear him praying,” said Brooks Lawrence, a rookie pitcher who was his roommate. “He’d be saying, ‘I can hit. I know I can hit.’ And he’d go out the next day and he wouldn’t hit anything.”9 At the end of the month the Cardinals sent Alston down to their Triple-A Rochester club and brought up Joe Cunningham, who was hitting .328 at Rochester.

Alston later said he began hearing voices during his first year in St. Louis, although he told no one. “I don’t remember what they said, but it scared me to death.”10 He also complained of a sore arm and back, and said he was constantly tired. Still, he put up strong numbers at Rochester: .297/.352/.455 in 79 games. After the season a doctor treated him for a thyroid ailment that was thought to be causing his fatigue.

For the next two springs Alston got token tryouts, only because Busch demanded it. Eight plate appearances in 1955, two in 1956. With left-handed batters Cunningham and the aging Musial manning first base, the club had no need for Alston. He turned in an outstanding year at Triple-A Omaha in ’56, batting .306 with 21 homers. But during the offseason the voices returned.

As Alston remembered it, a woman’s voice told him, “It’s time to meet your maker.” He drove out in the country from Greensboro and slit his wrist with a razor blade, causing only a minor wound. A deputy sheriff found him and sent him home.11 It’s not clear whether the Cardinals knew of the suicide attempt.

The next spring manager Fred Hutchinson decided Alston would never hit big league pitching and wanted to dump him. When Busch’s executives insisted that he be kept on the Opening Day roster, Hutchinson said, “If I wanted to play a clown, I’d hire Emmett Kelly.”12

Alston appeared in four games in the first weeks of the 1957 season, but his behavior had become too erratic to ignore. “I felt people were looking at me funny,” he said later.13 He had lost 15 pounds, down to about 175. Musial said, “The poor guy is so weak the bat seems to be swinging him.” The club sent him to a doctor, who put him in a hospital for treatment of what was described as “a nervous condition.”14

The first time he saw a psychiatrist in the hospital, Alston recalled, “He didn’t ask no questions or nothing, just administered shock treatment.”15 He rejoined the team in September and went 4-for-13 in five games.

The Cardinals wanted him to stay in St. Louis for additional treatment, but he went home to live with his father. He never returned to baseball. In early 1958 he was charged with assault with a deadly weapon and served 30 days on a chain gang before the balance of his sentence was suspended.

After midnight on a September night, Alston went to the New Goshen Methodist Church, splashed kerosene around the sanctuary, and burned it to the ground. He gave several explanations over the years. Once he said the voices told him to burn the church because the congregation needed a new building. Another time he said he had argued with one of his sisters and torched her church out of spite.

When daylight came, police arrested Alston and a judge ordered a psychiatric exam. He was found mentally incompetent to stand trial. Dr. John W. Turner testified that the defendant was schizophrenic and was dangerous during his “paranoiac phase.”16

Alston spent the next eight years in a state psychiatric institution. His discharge in 1967 turned out to be premature; two months later he set fire to his apartment and was committed again. Released in 1969, he continued taking medication and making regular visits to a mental health clinic for the rest of his life. In interviews in his later years, Alston was sometimes lucid, sometimes rambling and barely coherent. He never married or held a steady job, subsisting on Social Security disability benefits.

North Carolina A&T inducted Alston into its sports hall of fame in 1972. He occasionally showed up on campus to give batting tips to varsity players. By 1990 the 64-year-old was living in a nursing home when former Cardinal Joe Garagiola heard of his hardships. “When I called Tom Alston, he could hardly believe it,” Garagiola said. “He was so lonely.”17 Garagiola was one of the founders of the Baseball Assistance Team (B.A.T.), which provides financial aid to needy players and their families. With B.A.T.’s help, Alston was able to move into an apartment of his own.

As a result of Garagiola’s outreach, the Cardinals invited Alston to throw out the first ball at a game in June, recognizing his place in their history. Fans welcomed him with a warm ovation. The club also arranged for him to earn some money at an autograph show. “I had more fun that visit than I ever had when I was playing,” he said.18

Alston contracted prostate cancer and spent his final months in hospice care. He died at 67 on December 30, 1993.

Sportswriters and some of Alston’s teammates believed the pressure of being a pioneer and a $100,000 man caused his mental illness. “[B]ecause the Cards had paid so much money for him, he thought he had to live up to the price,” former roommate Brooks Lawrence said. “When he couldn’t, it broke him.”19

The explanation is more complicated, according to Dr. Jeffrey Swanson, professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine. “It’s certainly true that stress and pressure can exacerbate psychotic episodes,” Swanson said in an interview. “But you’d have a hard time arguing that stress and pressure can produce psychosis.”20 The National Institute of Mental Health says scientists think genetics, chemical imbalances in the brain, and environmental factors all may play a role in the development of schizophrenia.21

Alston never said publicly that he had been mistreated in baseball. His tombstone celebrates his time in the game; it is decorated with two birds on a bat, the Cardinals logo.

Additional Sources

Alston, Tom. Interview by Brent Kelley, June 17, 1992. SABR Oral History Collection.

Armour, Mark, and Dan Levitt. “Baseball Demographics, 1947-2016.” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

Reid, Kevin. “Tom Alston: The Baseball Pioneer Who Paid the Price.” Piedmont Ballpark News, undated clipping in Alston’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Revel, Dr. Layton, and Luis Munoz. “Forgotten Heroes: Chet Brewer.” Carrollton, Texas: Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2014. http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Chet-Brewer.pdf, accessed December 3, 2016.

Notes

1 Phil Collier, “Touching All Bases,” San Diego Union, April 10, 1954: b-4.

2 Jack Murphy, “Alston Hailed as $200,000 Product,” San Diego Union, May 6, 1953: b-3. Stepin Fetchit (the stage name of Lincoln Perry) was an early black movie actor who played dimwitted, subservient roles.

3 Collier, “Touching All Bases,” San Diego Union, January 29, 1954: a-22.

4 Jim Schlosser, Remembering Greensboro (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2009), location 1663.

5 Edward A. Harris, “Cards Give $100,000 and Four Players for Negro First Sacker,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 27, 1954: 28.

6 Collier, “Cardinals Buy Alston for $100,000, Four Players, In Record Minor Deal,” San Diego Union, January 27, 1954: a-17. Busch

7 Scott Pitoniak, “Voice from a tormented past,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, undated (1991) clip in Alston’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Ibid.

9 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper, 2000), 413.

10 Schlosser, location 1105.

11 Pitoniak. The timing of the suicide attempt is not certain. From context, the winter of 1956-57 is the most probable.

12 Bob Broeg, “Sports Comment,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 12, 1962: 4D. Kelly was a famous circus clown.

13 Schlosser, location 1707.

14 “Tom Alston Drops 15 Pounds, Sent to Hospital for Checkup,” Post-Dispatch, May 21, 1957, 4C.

15 Schlosser, location 1714.

16 “Ex-Baseball Player Ruled Incompetent,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, December 6, 1958: 5.

17 Kevin E. Boone, “Garagiola Goes to Bat for Ex-Players in Need,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 4, 1990: 6C.

18 Wendy Conlin, “Alston’s Ordeal,” Post-Dispatch, August 14, 1990: C1.

19 Golenbock, 413.

20 Jeffrey W. Swanson, interview by the author, January 24, 2017. Dr. Swanson emphasized that he was speaking generally and had no specific knowledge of Alston’s case.

21 National Institute of Mental Health, “Schizophrenia.” https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml, accessed January 24, 2017.

Full Name

Thomas Edison Alston

Born

January 31, 1926 at Greensboro, NC (USA)

Died

December 30, 1993 at Winston-Salem, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.