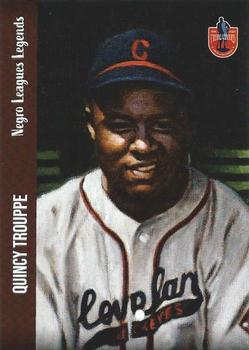

Quincy Trouppe

Quincy Trouppe’s passion for baseball led to a long career as player, manager, and scout. An exceptional catcher and switch-hitter, “Big Train” played on Negro League teams including the St. Louis Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, and the Homestead Grays. He also played for and managed the Cleveland Buckeyes, twice leading them to the Negro American League championship; the Buckeyes won the Negro World Series in 1945.

Quincy Trouppe’s passion for baseball led to a long career as player, manager, and scout. An exceptional catcher and switch-hitter, “Big Train” played on Negro League teams including the St. Louis Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, and the Homestead Grays. He also played for and managed the Cleveland Buckeyes, twice leading them to the Negro American League championship; the Buckeyes won the Negro World Series in 1945.

Trouppe competed at a high level across the Americas. His career took him to Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Canada, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. He was also known as “El Roro” (“The Baby”) to his Mexican fans, echoing another U.S. nickname, “Baby Face.”

At the age of 39, Trouppe signed with the Cleveland Indians, achieving his dream of playing in the major leagues, albeit briefly. Bob Feller of the Indians recalled that “Quincy just came in a little too late because he couldn’t get in during his prime. It’s a shame because there’s no doubt in my mind he would have been a very good major leaguer if blacks had been allowed into the big leagues when he was in his prime.”1 Trouppe later devoted himself to baseball, his teammates, and his fans in yet another role: historian/philosopher, as reflected in his book 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Baseball.

Quincy Thomas Troupe was born in Dublin, Georgia, on December 25, 1912. When he was born, his family name was spelled with just one ‘p’. For the purposes of this story, the spelling Troupe will be used until reference to 1946, when Quincy changed it to Trouppe, as he related in his book.

Troupe’s family background lay in slavery. The probate inventory of the estate of George Troup (1780-1856), 32nd governor of the state of Georgia, includes the names of more than 300 slaves. One of them was 21-year-old Obediah Troup, whose identity reflected the common practice of slaves assuming their owner’s surname, or being actual offspring. Obediah Troup married Katie (or Caty) and together they had eight children.2 One was Quincy’s father, Charles, who was born in 1867 – four years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

At least as late as 1900, census records still show the family name without an ‘e’ at the end. Charles and his wife Mary (née Williams) were married in 1891. Quincy was the youngest of their 10 children.

His father, as his grandfather had been, was a sharecropper in a racially divided area. Raised in a loving home, Quincy had for years been unaware of the full nature of tensions and conflicts between Blacks and Whites. However, around the age of 10, a particularly difficult situation involving his brother, Albert (“Buddy”), and the family’s White overseer awoke Quincy to the reality of racism. After this incident, Charles and Mary decided it best to leave Dublin for St. Louis, Missouri, where a family friend and an employment opportunity awaited. First, Charles and his sons Albert and George traveled to St. Louis. Within a few months, while the older children moved to northern states (Connecticut and New Jersey), Mary and five children, including young Quincy, moved to St. Louis. This all happened between 1921 and 1922.

In Missouri, Charles had rented a small house near the levee in South St. Louis. Charles promised to find a more comfortable space as soon as he and Albert earned enough through their work at the American Car and Foundry Company (ACF) in St. Charles, Missouri. Their rented home had no running water. Quincy recalled that he and his brothers needed to climb a fence, using a makeshift ladder, to retrieve buckets of water. In time, Charles secured a comfortable three-room home in the Compton Hill area of central St. Louis.

Although the family enjoyed comforts not available in rural Georgia, the all-too-familiar racial divide posed challenges. Later in life, Troupe attributed his abilities, interests, and sensitivities to life experiences – positive and negative. He loved the city and took advantage of its resources and opportunities. To assist his family financially, he took a paper route, which brought him to White neighborhoods and fistfights. He learned not only about support for and from family but also how to box, a talent which would bring him amateur boxing championships.

When time and money permitted, Troupe went to the movies, even though blatant discrimination forced him to sit in the colored section of theaters. The movies, and the technology behind them, thrilled him.

Also, as he wandered the many neighborhoods of St. Louis, he found baseball and the St. Louis Stars of the Negro Leagues. He met players, including James “Cool Papa” Bell, who encouraged Troupe to pursue baseball; in this pursuit, he recalled that he “ate, slept, and breathed baseball.”3 This fed the mentorship of his favorite elementary school teacher, Miss Harmon. It was she who encouraged Quincy to play baseball and to become a catcher.

Troupe attended Vashon High School, the newer of “two high schools for the colored” in St. Louis.4 Vashon happened to be across the street from the St. Louis Stars’ ball park. In his final year at Vashon, 1929, his team faced Sumner High School (the first Black high school in St. Louis) for the city championship. The game was played at the Stars Park and would be umpired by a Negro League umpire, Bill Donaldson. Adding to the excitement, Stars players Cool Papa Bell, Mule Suttles, and Stringbean Trent were in attendance. After the game, which Vashon won, Troupe noticed Bill Donaldson in conversation with Vashon’s Coach Sutton. Donaldson coached an American Legion League team named “Peerless” in St. Louis and wondered if Quincy would like to play on that team. Troupe enthusiastically joined as a pitcher/catcher.5 The “Peerless” team won the American Legion League Colored Division.

Soon thereafter, Donaldson sought a true playoff game with the (White) American Legion League champions. However, he could only schedule an exhibition game between the two teams – the game concluded in a 3-3 tie. This represented another part of Troupe’s education around racism; segregated baseball continued.

It was around this time that Quincy’s father, Charles, suddenly passed away. He and his family grieved deeply at the loss. However, his loving family and devout Baptist upbringing reminded him that he was not alone and that he could continue his life’s journey, which included baseball. He took on duties as batboy for the St. Louis Stars, and soon started training with the team. His skills improved, and, while visiting his brother in New Jersey, he played briefly with the Newark Browns.

Troupe wanted to be a catcher, but he recognized that he needed to develop his skill, and thus, to find a team that did not already have an established catcher or two. For this reason, he found himself on the mound rather than behind the plate. Although just out of high school, he now competed with Negro League greats, including Josh Gibson. After returning to St. Louis from New Jersey, he had the opportunity to play with the Stars versus the Homestead Grays; here he witnessed the power of Gibson, who sent one of Quincy’s fastballs more than 400 feet.6

Upon returning to St. Louis, Troupe took a job at a chemical plant. He also played basketball at the local YMCA. At times he felt that professional basketball might be an option for him, but he knew that baseball was his true calling. His life began to revolve around baseball. In 1931, at age 19, Troupe signed his first professional baseball contract with the St. Louis Stars. Many Negro Leaguers played with multiple teams in the course of a season. From 1931 to 1935, Troupe also played with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, the Homestead Grays, and the Kansas City Monarchs, as well as the Posey brothers’ short-lived team, the Detroit Wolves.

In 1933 Troupe signed a contract with the Chicago American Giants. He did not report to the team for spring training because at the time he was a student at Lincoln University in Jefferson, Missouri. One of his fondest memories of his time with the Giants was a game versus Satchel Paige in which he hit a triple, single, and a home run off Paige. This began a lifelong friendship between the two men.

Troupe decided not to return to Lincoln University in the fall of 1933. He followed baseball opportunity to North Dakota, where he played for an integrated team, the Bismarck Cubs. Owner-operator Neil Churchill recruited many Negro League stars for this team. It was Troupe who encouraged Paige to try North Dakota as well.

Troupe received pay for some of his play, but on occasion received no pay. One of those games was a postseason match, organized by his brother, in St. Louis before a hometown crowd and his hometown sweetheart Dorothy Smith.7 Troupe won the game with a home run. At the end of the 1935 season, he returned home to St. Louis, where he played basketball and began to box, as a heavyweight. When full-grown, Troupe was a big man, standing 6-feet-2 and weighing 225 pounds.

Troupe won local championships, including the first Golden Gloves Tournament in St. Louis. At a Midwestern tournament in Chicago he won three fights and lost one. At the National Tournament in Providence, Rhode Island, he had four wins and was presented the heavyweight trophy cup by the state’s governor, Theodore Green. In Providence, Quincy met Joe Louis, then an up-and-coming heavyweight contender. Troupe continued his amateur boxing in a tournament in Cleveland; he and future light heavyweight champion Archie Moore reached the semifinals, and Len Franklin won the heavyweight division.

Troupe considered professional boxing as a career, but one evening after he and Archie Moore met with a baseball friend, he realized again his love for baseball. Plus, as Moore said, “Quincy, I don’t think you could ever be a fighter. You’re just too nice. You’re not the mean type…You have the punch. You move faster than the average heavyweight, and you’ve got a real sharp left jab. But you are not mean.”8

In 1936, Troupe returned to North Dakota and, through Neil Churchill, played in a tournament in Wichita, Kansas. Troupe and Hilton Smith, the only two men of color on the all-tournament team, attracted attention from major-league scouts. One scout said that had they been White, he would recommend signing each for $100,000.9 Troupe finished the season with stints on the Kansas City Monarchs roster and played into the postseason versus major-league all-stars.

Troupe did not play baseball in 1937, needing time both to heal his shoulder (a boxing injury) and to settle his relationship with Dorothy Smith. While he worked as a salesman for a milk company, he stayed connected to baseball through weekend amateur games. The following year, Quincy and Dorothy were married, and, although he would be away from his new wife, he signed a contract to play baseball with the Mound Blue team (aka Indianapolis ABC’s) for the 1938 season. His fine play earned him a spot in the in the East-West All-Star Game to be played in Chicago.

At the season’s conclusion, one of his teammates, Ted Strong, encouraged Troupe to try out for the Harlem Globetrotters. The choice was clear to Quincy, however – his commitments were to Dorothy and baseball. During that offseason, he worked for a steel company, which he called “the hardest job I’ve ever had.”10 In March, he received a call to report to spring training; he made arrangements with his employer for a leave of absence. Although he “really didn’t want to leave [his] wife,” he accepted this as “part of baseball.”11

Soon after arriving for spring training, Troupe received a telegram from the Carta Blanca team of Monterrey, Mexico, which offered him an opportunity on recommendation from Cool Papa Bell. He accepted the team’s offer and left for his first of several baseball seasons outside the United States.

During that first season in Mexico, Troupe received word that his son, Quincy Jr., had been born on July 22, 1939. A successful season, an offer to return, and an unwillingness to leave his family led the new father to drive, in 1940, to Monterrey with Dorothy, Quincy Jr. and teammate Theolic Smith. Unfortunately, after reaching Mexico, Dorothy and little Quincy became ill and needed to return to St. Louis. They recovered and the family welcomed a second son, Timothy.

Troupe recalled the 1941 season, his second in the Mexican League, as very competitive – that year Josh Gibson, Ray Dandridge, Willie Wells, Leon Day, and other Black stars were there.12 When the season was over, Troupe formed and managed (his first managerial post) an all-star team to tour the United States. He extended his 1941-1942 season with winter baseball in Puerto Rico. His baseball play had kept him away from St. Louis and his family for most of that season; unfortunately, it became clear that he and Dorothy were drifting apart.

In 1942, as World War II intensified, Troupe wanted to enlist in the military. He was rejected for being married with dependents, and therefore decided to work in a defense plant, the Curtiss-Wright Aircraft Company. In 1943, while working as an inspector at the aircraft company, he received a letter from Jorge Pasquel of the Mexican League. Sr. Pasquel wanted Troupe to play ball in Mexico, but Quincy’s job classification did not permit him to leave the United States. Through negotiations with the draft board, Sr. Pasquel arranged for him to leave the U.S. to play again in the Mexican League.

After the 1943 season, Troupe returned to work in an aircraft plant, and with another baseball season ahead, again received a letter from Pasquel about playing in the Mexican League. This time, evincing his power and influence, Sr. Pasquel arranged a sort of trade – 80,000 Mexican workers, to increase U.S. manpower, for two baseball players, namely Quincy Troupe and Theolic Smith. Quincy noted that “George [sic] Pasquel was a powerful man. It still staggers my mind how he was able to bring about this astounding exchange.”13

With 1944 came a letter from the owner of the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League, asking Troupe to join his team as player-manager. He accepted the offer and in his first season, 1945, led the Buckeyes to the Negro World Series, defeating the Homestead Grays four games to none. He remained with the Buckeyes through the 1947 season.

At the conclusion of the 1945 season, Troupe received word from a Venezuelan consulate official about joining a team to tour that country. He became a member of the American All Stars with other players from the Negro Leagues, including Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Sam Jethroe. It was also at this time that Troupe and his wife, Dorothy, officially separated – the baseball life had taken its toll.

In 1946, Troupe signed to play winter ball in Venezuela with the Magallanes club. Also in 1946, after having played in Latin America for six seasons, he changed the spelling of his surname to Trouppe, reflecting the pronunciation of his name by his Mexican fans – “Troo-pay.”14 It’s noteworthy, though, that American newspapers continued to use the “Troupe” spelling.

In 1947, player-manager Trouppe won a second NAL pennant. Among others, the Cleveland team featured pitcher Sam Jones. However, the Buckeyes lost the Negro World Series to the New York Cubans. For the 1948 season, Trouppe was traded to the Chicago American Giants.

Baseball had been and continued to be a year-round occupation for Trouppe. He played winter ball for teams in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Cuba, and Colombia. He played spring and summer seasons in the United States, Mexico, and Canada. During offseasons, he played exhibition games with Negro League all-stars versus major-league all-stars. Despite many challenges, including racism, salary constraints, and playing nearly every day, Trouppe recalled his many achievements.

One particularly fond memory came from his time as player-manager of the Caguas Criollos in the Puerto Rican League. Trouppe himself hit a home run in the 10th inning of the seventh game of the playoff finals against Mayagüez to bring Caguas the 1947-48 championship. “This was one of the greatest days of my baseball life. The people made me Honorary Mayor for the day, and because I always loved children, I declared the day a holiday, closing down all the schools in town.”15

Dorothy finalized her divorce from Trouppe in 1949, the year he was traded from the Chicago American Giants to the New York Cubans. Prior to the start of the season, Trouppe was approached to play for a team in Canada’s Provincial League, the Drummondville Cubs. With the decline of the Negro Leagues, many Black players found this league to be a viable alternative. Despite some misgivings, including not speaking French (he did speak Spanish fluently), he decided to play in Canada. Along with star pitcher Sal Maglie and young first baseman Vic Power, Trouppe helped his team to a league championship over the Farnham Pirates.

Trouppe returned to play/manage in the Mexican League for the 1950 and 1951 seasons. In October 1951, he met with Abe Saperstein, the Harlem Globetrotters impresario. Saperstein, who was also involved with baseball, possibly had a position for him in so-called Organized Baseball. Shortly after that meeting, Trouppe traveled to Venezuela to play winter ball, and there he received a call from Hank Greenberg, general manager of the Cleveland Indians. Greenberg told Trouppe that the Indians were interested in him and offered a minor-league contract with the team’s affiliate in Indianapolis. Greenberg reminded Trouppe that it would be “up to you to make the team.”16

At age 39 – though newspaper reports knocked a full decade off – Trouppe did make the Indians in 1952. He became the first African-American catcher in the American League.17 To his dissatisfaction and frustration, however, he spent most of his time with the team on the bench behind Jim Hegan and Birdie Tebbetts.

Wearing number 16, Trouppe played in his first big-league game on April 30, 1952. Four days later, at Griffith Stadium in Washington D.C., he replaced Tebbetts behind the plate in the seventh inning. In the middle of that inning, old Buckeyes teammate Sam “Toothpick” Jones came on in relief – they formed the first African-American battery in AL history.

Trouppe got his first start with the Indians the following day. His only other start came on May 10. He had his first hit and scored his first run in the majors; it turned out to be his final game with the Indians and in major-league baseball. In his stint with Cleveland, he had played in six games, and had 11 plate appearances, with one hit.

Trouppe was then demoted to Indianapolis. Reports of the time said that the Indians wanted him to train young pitchers there. According to Trouppe, though, Hank Greenberg told him that he didn’t have enough of a record to go on to remain in the majors – which left him incredulous.

Although disappointed, Trouppe played well. He hit six home runs in his first two weeks with the minor-league club. Frustration continued, however, as he learned that catcher Joe Tipton had been bought from the Philadelphia Athletics.18 Yet, there was joy in his life – this was also the year he married Myralin Donaldson. After their wedding, they traveled to Caracas, Venezuela for winter ball; she soon returned home when they realized she was pregnant.

By the spring of 1953, Trouppe had chosen not to report to Indianapolis. The team’s manager – Birdie Tebbetts – suggested that Quincy take time to contemplate his decision. He would not return to the Indians organization. Instead, for the first time in his career, Trouppe traveled to the Dominican Republic, having received an offer to play “that was too good to refuse.”19

However, after three weeks of spring training, Trouppe received a telegram from the St. Louis Cardinals regarding his application for a scouting position. He returned to St. Louis, met with Cardinals owner August A. Busch and chief scout Joe Mathes, and was offered the job. Trouppe accepted the position, becoming the first African-American scout in the Cardinals organization. As Trouppe assumed his new role in Organized Baseball, he welcomed his new daughter, Stephanie Marie, born May 13, 1953.

Trouppe enjoyed his scouting responsibilities but met disagreement and challenge as he recommended players. He had opportunity to meet and observe talented players, but he was consistently bewildered when some of his recommendations were rejected. They included Ernie Banks (who signed with the Cubs), Roberto Clemente (originally a Brooklyn Dodgers farmhand), and Vic Power (New York Yankees).

Trouppe returned to Puerto Rico for the 1956-57 winter season as manager of the Ponce Leones. In 1957, however, the Cardinals management decided that Trouppe’s approach to scouting did not fit with the team’s philosophy, and he learned that his services were no longer needed. Despite his disenchantment with the Cardinals organization, Quincy respected some colleagues, in particular Joe Mathes.

At the age of 45, and now out of baseball, Trouppe took a position with the St. Louis Land Clearance Authority, helping to relocate families to “standard housing quarters.”20 All appeared to be going well until he returned home one day and realized that Myralin and little Stephanie were leaving him. He and Myralin divorced and California became his next destination.

In 1963, three years after his arrival in California, he met and married Bessie Cullins. Together they served as proprietors for a senior citizen’s home, the Queen Anne Manor, in Los Angeles.21 They also opened a restaurant which they named Trouppe’s Dugout.

Around 1967, hoping to return to baseball, Trouppe contacted George Silvey of the Cardinals (Trouppe had worked with Silvey during his earlier stint with the Cardinals).22 Within a day, Harrison Wickel, a former player and manager turned scout, met Trouppe in his restaurant – there he signed a contract. He scouted talent in California for the Cardinals until 1970, when he and Bessie left California for Hattiesburg, Mississippi. After Bessie’s passing in 1988, Quincy returned to St. Louis.

Quincy Trouppe made “enduring contributions” to baseball and history.23 They include his 1977 self-published book, 20 Years Too Soon (which has since been republished by the Missouri Historical Society). He compiled a valuable photograph and motion picture collection – in fact, he supplied almost all of the Negro League footage shown in the Ken Burns documentary Baseball.24

Trouppe is remembered as much for his character in baseball as he is for his achievements. Riley Stewart, pitcher for the 1948 Chicago American Giants, noted:

“He was one of the few managers that would fit in any era, now or in the past…He was a real gentleman. He was clean-cut, and well dressed. He was a model for the guys on the team. He never cussed. He might say “dawg gone.” I never played for a finer gentleman. And he knew the game – very well.”25

Late in life, Quincy Trouppe suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. He died on August 10, 1993, in Creve Coeur, Missouri. He is buried at the Calvary Cemetery and Mausoleum in St. Louis.

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on Quincy Trouppe’s book 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Integrated Baseball. Also helpful were newspaper clippings from the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York; the Laurens County African American History website; and Leslie Heaphy’s The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960.

Photo credit: Quincy Trouppe, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Quincy Trouppe, 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major League Integrated Baseball (St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1995), 4.

2 Laurens County African American History, “The Troupes: The Story of a Laurens County Family.” http://laurenscountyafricanamericanhistory.blogspot.com/2009/07/troupes.html (last accessed December 23, 2015).

3 Trouppe, 4.

4 Trouppe, 19.

5 Trouppe, 21.

6 Trouppe, 27.

7 Trouppe, 36.

8 Trouppe, 81.

9 Trouppe, 66.

10 Trouppe, 68.

11 Trouppe, 69.

12 Trouppe, 74.

13 Trouppe, 82.

14 Trouppe, 99.

15 Trouppe, 105.

16 Trouppe, 110.

17 Laurens County African American History, “Quincy Trouppe – Dublin’s All Star Player.” http://laurenscountyafricanamericanhistory.blogspot.com/2009/03/quincy-trouppe-dublins-all-star-player.html (last accessed December 22, 2015)

18 Trouppe, 113.

19 Trouppe, 116.

20 Trouppe, 124.

21 Larry Lester, Introduction to 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Integrated Baseball, by Quincy Trouppe (St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1995), 5.

22 Jim Sandoval and Bill Nowlin, ed. Can He Play: A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2011), 129

23 Lester, Introduction to 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Integrated Baseball, 7.

24 Lester, 6.

25 Lester, 4.

Full Name

Quincy Thomas Trouppe

Born

December 25, 1912 at Dublin, GA (USA)

Died

August 10, 1993 at Creve Coeur, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.