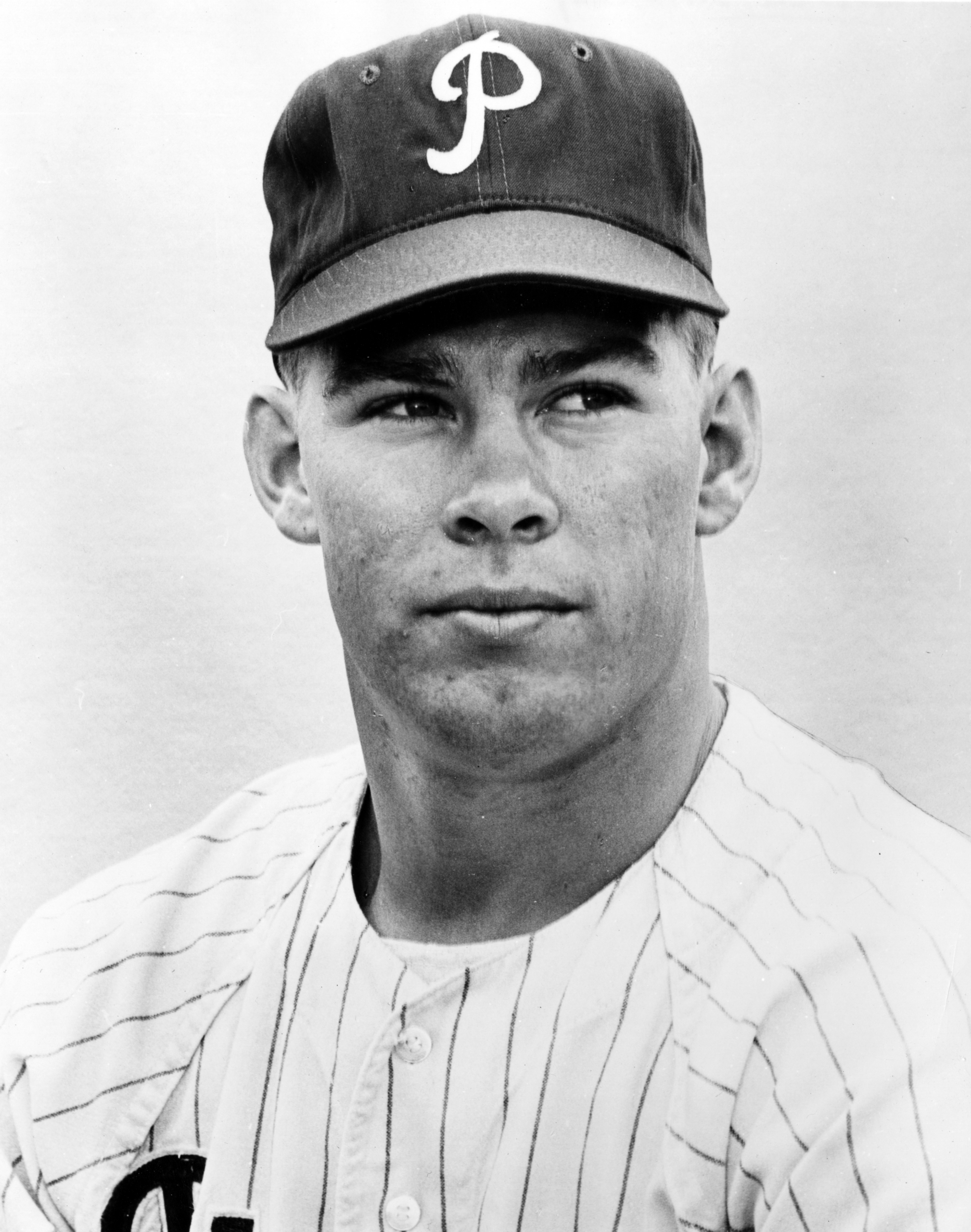

Costen Shockley

Suggest today to Costen Shockley that judging by the newspaper headlines of 50 years ago he must have been quite a high-school baseball player, and he replies with a prideful chuckle that conveys barely a trace of conceit, “Yeah, I was pretty good.”

Suggest today to Costen Shockley that judging by the newspaper headlines of 50 years ago he must have been quite a high-school baseball player, and he replies with a prideful chuckle that conveys barely a trace of conceit, “Yeah, I was pretty good.”

Indeed he must have been. After dominating on the baseball diamond for three years at Georgetown (Delaware) High School, he signed a contract with his favorite major-league team, quickly ascended the ranks of the minor leagues, and four years later was in the majors. In his second major-league game, he hit a home run. The next year, he hit a grand slam. And then, at the age of 23, rather than return to the minor leagues, where, he felt, “I had nothing left to prove,” Costen Shockley abruptly walked away from the game and returned for good to his hometown. Today, he admits he has no regrets for, in the end, he chose family over baseball.

Family has always been the most important thing in Shockley’s life. Born on February 8, 1942, in Georgetown, John Costen Shockley was the eldest of seven children, four girls and three boys. (Costen was 16 years old when his youngest brother was born.) As to the origin of his somewhat unique middle name, Shockley has no idea. Named after both his great-grandfathers, as a boy Shockley briefly tried using his first name, John, but for as long as he can remember his parents instead called him by his middle name. So Costen it’s always been. (Among his teammates, he was usually referred to as Cos.)

As with many boys, sports were central to Shockley’s youth. His father, Chester, who spent his entire career working for the Delaware Department of Transportation (his mother, Dorothy, worked at home raising the seven children), gets much of the credit for young Costen’s development. While in later years Shockley remembered his father as simply “a good baseball player,” in March 1962, the aspiring major leaguer told a reporter from the Salisbury Times in Maryland, “My dad was a ballplayer until he lost three fingers on one hand. He always encouraged me and helped me when I showed an interest in the game. Out in the backyard he hung up a tire and made a backstop when I was just starting. I used to throw through that tire by the hour. Then he worked with me on other phases of the game, too.” By 1956, Shockley was a Pony League star.

With such early devotion to the game, by the time Shockley entered the seventh grade at Georgetown High School (the school comprised grades 7 through 12), he was already an accomplished baseball player. His athletic skills weren’t limited solely to baseball. In football, which Shockley confesses was probably his favorite sport (“I liked the contact”), he played running back and linebacker, and also handled the kicking and punting duties (he gave up football following his junior season to concentrate on baseball). On the basketball court he was the team’s leading scorer. During his junior season, in 1958-59, Shockley, a southpaw shooter with a “nifty one-handed jump shot,” scored 385 points in 14 games, a scoring average of 27.5 points per game. The next year he finished fourth in the league in scoring, with an average of 19.1 points per game.

It was in baseball, however, that Shockley proved most dominant, both on the mound and at the plate. Entering his senior season, Shockley had posted a pitching mark of 31-3 (including three no-hitters) and a batting average that hovered around .600. By that time, he remembered, “I had already been contacted by every major-league team.” Besides Georgetown, scouts had also seen him compete for two years [1958 and ’59] with Hebron in the semiprofessional Central Shore League, as well as with the local American Legion team.

His senior season, 1960, promised to be his best. On April 7, with numerous major-league scouts in attendance, Shockley threw a no-hitter. Unfortunately, though, his season ended prematurely when he was diagnosed with hepatitis little more than a month later. (Shockley finished his career at Georgetown with a pitching record of 37-3, four no-hitters, and a .527 batting average.) For two weeks Shockley remained hospitalized in serious condition, and as the summer progressed, most major-league scouts lost interest in him as a prospect. Remembering that summer years later, Shockley related, “Only about five teams stayed with me throughout.” One of those teams was the Phillies, Shockley’s favorite team, and on July 17, 1960, he signed with veteran Philadelphia scout John Ogden for $50,000. In March 1962, Sherry Robertson, farm director of the Minnesota Twins, remarked after watching Shockley hit during spring training: “He’s going to be a hitter, that boy. I just wish we had signed him.

As Shockley began his professional career in March 1961, reporting to the Phillies’ training camp in Clearwater, Florida, he didn’t know what position he was going to play; the club had yet to communicate with him about his future. “I didn’t know what the Phillies had in mind,” he later recalled,“which way they wanted me to go, pitching or first base.” Accordingly, he arrived for his initial practice with both a first baseman’s glove and a pitching shoe. As it turned out, though, the Phillies had decided he was too good a hitter to keep inactive three out of every four days, and upon meeting his prized rookie for the first time, Philadelphia manager Gene Mauch told Shockley, “Get rid of that shoe; you’re going to be a first baseman.” With that, Shockley’s future was decided.

From the outset, the new first baseman drew praise from the Phillies’ manager. Speaking to a sportswriter, Mauch expressed confidence that Shockley, who had been assigned to the team’s minor-league training camp in Plant City, Florida, “appears to me to have all the tools of a future big leaguer. I like the way he swings that bat. He had good power, good wrists, and the kid hits breaking stuff, too.” That assessment came after Shockley’s first intrasquad game, when he stroked two hits, one of them a double, against future Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts. “Both [hits] were genuine base knocks,” Mauch enthused.

Yet the manager cautioned that Shockley’s defense was still a work in progress. “He needs a lot of polish around first base,” Mauch said, “like proper manner in shifting feet, holding runners on base, and fielding bunts. But the boy’s attitude is wonderful. He’s eager to learn.” It was a theme that would be echoed several more times before Shockley was through.

In April 1961, the 19-year-old Shockley began his professional career in Twin Falls, Idaho, playing for the Magic Valley Cowboys in the Class C Pioneer League. In 126 games, all as a first baseman, he produced a brilliant rookie season, finishing second in the league with a .360 batting average (the highest in the entire Philadelphia organization), while collecting 31 doubles, 6 triples, and 23 home runs (for a slugging percentage of .598), with 108 runs batted in. That performance earned Shockley both All-Star and Rookie of the Year honors and so impressed the Phillies that in October they announced Shockley had been added to their 1962 roster.

When he reported to Clearwater for spring training in March 1962, Shockley was a married man. On January 27, at the Grace Methodist Church in Georgetown, John Costen Shockley wed his childhood sweetheart, Mary Lou Parker (they produced two sons, Curt and Jeff). As the couple honeymooned in Clearwater, Shockley, as noted in a clipping in his Hall of Fame file, “smashed line drives to all fields off all kinds of pitching.” Watching his budding star, Mauch was again effusive in his praise of the natural swinger. (“Don’t let anybody change your swing,” scout John Ogden had advised Shockley upon drafting the young man, and Shockley never did.) “There’s our next first baseman,” Mauch told the press on March 22. The manager predicted that Shockley would play in the minors at least two more seasons, moving into the regular lineup by 1964, “when [current first baseman] Roy Sievers is finished.”

On April 16, Shockley was sent to Philadelphia’s Class A entry in the Eastern League, the Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Grays, where he joined future Phillies teammate Richie Allen in playing for manager Frank Lucchesi. Class A proved more challenging than his previous dazzling year in Class C, as Shockley’s average fell to .282 and his slugging mark to .417. Among his 144 hits, Shockley collected 29 doubles and 5 triples, matching his numbers from the previous year, but his home runs tailed off to just 10 and RBIs to 82. The main culprit in that decline, Shockley told the press in July 1964, had been too many strikeouts the previous season at Magic Valley.

“The air was thin out there,” he said. “Anything was liable to go out of the park. Any night I got a couple of hits, I’d go for the long ball the last two times up. As a result, [in 1961] I struck out a lot. I guess it was then I decided to quit worrying about home runs.”

He clearly didn’t worry about them the next season either. In 1963, Shockley was again promoted, this time to Chattanooga in the Double-A South Atlantic League. That season, in 127 games, Shockley again finished second in the league in batting, with an average of .335. While his home runs and RBIs again tailed off (8 and 74), he nonetheless raised his slugging percentage to .492 (27 doubles and a league-leading 12 triples), while reducing his strikeouts from 77 in 1962 to just 49. In addition to leading the league in triples, Shockley also led in sacrifice flies (8), and increased his on-base percentage from .356 at Williamsport to a career-best .373. In the final month of the season, Shockley’s average was .420, and a year later he reflected, “For a month or so, everything was a base hit. I don’t know what happened. It seemed I’d get two or three hits every night.” He was just a season away from his major-league debut.

“The Phillies are going to give Shockley every chance to win the first base job,” noted the press the following spring. “His instructions are to report February 27 with the pitchers and catchers.” He came to camp in outstanding shape. During the winter, Shockley, now 22 years old, had worked out with the University of Delaware track coach, and came to camp 12 pounds lighter than the previous year. Moreover, the Phillies timed his speed to first base at 3.7 seconds. In addition to the veteran Sievers, now 37 years old and whom manager Mauch hoped to rest against right-handed pitching, Shockley’s competition was another left-handed hitter, 26-year old John Herrnstein, a 6-foot-3, 215-pound former University of Michigan fullback. Asked on March 19 to assess the battle between the two, Mauch said, “Herrnstein has the inside track at the moment” due to his ability to play the outfield. “Shockley, always a good spring hitter, is not slugging the ball as I expected him to.” (He was 0-for-5 in two exhibition games.) ”Still,” continued Mauch, “I’m weighing the possibility of keeping both.”

But he didn’t. On April 9, after a less than stellar spring, Shockley was sent to Little Rock, home of the Phillies’ Triple-A team in the Pacific Coast League, the Arkansas Travelers. Once again his manager was Frank Lucchesi. If Shockley had heretofore been a high-average hitter who sprayed line drives to all fields, this time Lucchesi saw a much different hitter; by 1964, Shockley had become a pull-hitting home run machine.

He was hot right out of the gate. From April 27 to May 15, Shockley hit safely in 19 consecutive games, delivering 15 RBIs in one seven-game stretch. Later, during a 12-game stretch from May 30 through June 9, Shockley hit four homers in eight games and drove in 11 runs on eight hits. As the season progressed, opposing managers employed a shift against hi m, and Shockley later recalled, “That shift cost me some hits.” In October, Grady Hatton, manager of the Oklahoma City 89ers, offered that “we couldn’t get that guy out and we tried pitching him every way there was.”

Shockley credited much of his newfound power to Arkansas’ ballpark, Travelers Field. With dimensions of 340 feet down the right-field line and just 360 to right-center, the left-handed swinger realized early in the season that “this park is better suited for me than any other I’ve played in. I’ll hit some fly balls to right-center that will go out of here.” Indeed, by July, the press recounted that “Shockley has blasted some towering blows halfway up the light towers in that direction and across the street beyond the fence.”

His defense had improved, too. Having last seen Shockley two years before, Lucchesi commented in July, “He improves every year. … He seems more aggressive in the field. His range is at least average and I think it will get better.” Also, Lucchesi said, “He has a good arm for a first baseman.” Early on, the manager had diagnosed a problem with the way Shockley fielded his position. “I noticed he was handling the mitt improperly on certain throws,” Lucchesi said. “I’m glad we found out. It was something that was easy to correct.”

By July 15, Shockley had already posted a full season’s worth of offensive production: a batting average of .300, with 24 home runs and 70 RBIs in 90 games. The Travelers were in first place in the PCL and Shockley was being counted on to drive the team toward the league title. Then he got the call for which he’d long been hoping. With injuries to Sievers and catcher Gus Triandos, the Phillies were in dire need of extra-base power. Accordingly, on July 16, they summoned Shockley to join the big-league club.

The call-up took the young man by surprise because Philadelphia was well-stocked with left-handed hitters; it was right-handed power they lacked, but “there was no answer [in the minors] to our right-handed-hitting situation,” Mauch explained. (On the same day, the team sold Sievers to the Washington Senators.) Five of Philadelphia’s last six losses, in fact, had come against left-handed pitching. Mauch, however, had done his homework. After examining Shockley’s at-bats, he had been surprised by the young slugger’s production against left-handed pitching. Before promoting Shockley, Mauch had asked Lucchesi how the left-handed swinger, who had hit half of his 24 home runs against left-handers, had fared against them.

“He told me Costen got a lot of big hits for him off southpaws,” Mauch said.

“Were they squibs?” Mauch asked.

“No,” replied Lucchesi. “He hit the ball with authority.”

So Mauch summoned the young first baseman. “That’s what we need,” he told the press, “someone to hit those southpaws.”

At the time it didn’t appear to be a short-term promotion. “We didn’t bring (him) up to sit on the bench,” said Mauch. “Shockley will be given a chance to play first base for the Phillies. I’m giving him a full shot at the job. … And he’ll hit against all types of pitching.”

The manager wasted little time getting Shockley into the lineup, and the rookie wasted little time validating Mauch’s confidence in him. On July 17, at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, the first baseman made his debut. Batting sixth against Reds right-hander Joey Jay, Shockley walked in the top of the second. After grounding out in his next at-bat, he led off the seventh inning with the score tied 2-2 and singled for his first major-league hit, later scoring on a single by Tony Taylor. In the eighth inning, with Danny Cater at second base, Shockley grounded to shortstop and advanced Cater to third, from where Cater eventually scored the winning run on a squeeze bunt by Clay Dalrymple.

Then next day, Shockley hit the ball a little farther. He was again in the starting lineup against the Reds, this time facing right-hander John Tsitouris. Shockley had batted sixth in his debut, but Mauch moved him up to hit second against Tsitouris, and despite a dismal 14-4 Phillies’ loss, Shockley hit his first career home run, a solo blast, for his only hit in five at-bats. After two more hits the next day in the first game of a doubleheader, Shockley was finally held hitless in the nightcap, and after 16 major league at-bats, the lefty swinger was batting .250.

It hadn’t been a splashy performance, but at least Shockley was now a big leaguer. The press gave him a brief mention, noting not only that the rookie had shown “good knowledge of the strike zone, an ability to hit major-league pitching and some power,” but that he also “got his job done at first base” and “ran the bases well.” Soon, however, Shockley’s initial stay in Philadelphia was over.

On July 29, with the first-place Phillies holding a half-game lead over San Francisco, Shockley was sent back to Little Rock. In eight games with the Phillies, he had batted .207 (6-for-29) and connected for his lone home run. Contrary to Mauch’s earlier statements, however, that Shockley would “face all kinds of pitching,” the lefty swinger had been platooned, facing only three left-handers, and now the Phillies, according to Mauch, needed right-handed hitters “desperately.” (When Shockley was sent down, right-handed-hitting Pat Corrales was called up.) So Shockley dutifully reported to Little Rock, and immediately picked up right where he had left off — hitting home runs.

He hit a lot of them, and the Travelers kept winning. By season’s end, Shockley had blasted a league-leading 36 home runs (while also batting .281, compiling a .914 OPS and tying for the league lead with 112 RBIs) for a team that hit a record 208 round-trippers. (On September 5, he hit two, numbers 33 and 34, against Denver’s Phil Niekro in a 4-3 Little Rock victory.) More importantly, with a 95-61 record, Little Rock clinched the PCL’s Eastern Division and faced West winner San Diego in a seven-game series for the PCL crown. Little Rock lost the series, four games to three, despite two home runs by Shockley.

When it was over, the slugger reaped the rewards of an outstanding minor-league season. On September 16, he was one of four Travelers named to the PCL All-Star team. Later, he finished second to San Diego’s Tony Perez in voting for the Most Valuable Player. Finally, Shockley was named the league’s Rookie of the Year, garnering 45 points to Perez’s 35. Recalled by Philadelphia at the conclusion of Little Rock’s playoffs, Shockley played in three more games for the Phillies and finished his major-league season with a .229 average, one home run and two RBIs in 11 games. They turned out to be the only games he ever played for his favorite major-league team.

Why? The Phillies had run out of options on their young first baseman. Despite his 36 home runs at Little Rock, Shockley’s future with the team seemed unsure. Then, at the annual winter meetings, the Phillies traded for veteran first baseman Dick Stuart from the Red Sox, and it was clear that the 22-year old Shockley was no longer in Philadelphia’s plans. That was assured a week later when Shockley and left-handed pitcher Rudy May were traded to the Los Angeles Angels for veteran left-handed pitcher Bo Belinsky.

What soured the Phillies on their young prospect is unclear. Perhaps Mauch, who had clearly been pleased the previous spring when Shockley “hung out line drives to all fields,” hadn’t been happy with the slugger’s transformation to a pull hitter, or perhaps with Shockley’s perceived defensive liabilities at first base, though his fielding average in nine games at the position was .968, with two errors in 63 total chances.

Today Shockley offers some personal insight into the trade. During the winter of 1964, Mary Lou Shockley was pregnant with the couple’s first child. It was a complicated pregnancy, so when the Phillies asked Shockley to play winter ball, he said in 2009, “I told the Carpenters (the Phillies’ owners) I’d go to winter ball once I knew my wife and newborn were okay.” Eventually, Mary Lou successfully delivered a healthy son, “but when I told the team I was ready to leave for winter ball, they told me I’d been traded to the . . . Angels.”

It took some cross-country bickering before the left-handed slugger joined the team. When the Angels opened their training camp in Palm Springs, California, in February 1965, Shockley remained at home in Georgetown, “hunting ducks and rabbits back in Delaware” with “his prize setter named Lucy.” Angels manager Bill Rigney, when asked about his new acquisition, commented to the press, “I’m impatient to see this youngster,” and outlined his plans for first base, where “we would like to be able to platoon Shockley with Joe Adcock.” Of the veteran right-handed-hitting Adcock, Rigney said, “[W]e know that Joe can’t play the whole season, and Shockley would be the fellow who can give us something on the left side.” If only Shockley were in camp.

It was a strange circumstance that kept him away. According to Shockley, when the Phillies had signed him in 1961, the team had committed to rewarding him after 30 days in the major leagues with a bonus of $20,000. As he was now just two days shy of that mark, he demanded that Philadelphia honor their commitment should he play for two days with the Angels. The Phillies, however, denied any such agreement and stated that the final payment of his original $50,000 bonus had been paid in December or January. Naturally, the Angels felt no obligation to pay any portion of the money, and Angels’ General Manager Fred Haney said, “We will wait one week and then put Shockley on the failure-to-report list which voids that part of the trade.” Finally, after appealing to Commissioner Ford Frick, and reaching a salary agreement with Haney, Shockley signed an Angels contract on March 8 and reported to camp.

He arrived in great shape. During the winter Shockley had refereed basketball and trained bird dogs, and he subsequently had an outstanding spring, finishing with a team-high batting average of .383. Consequently, on April 13, 1965, against the Cleveland Indians on Opening Day at Dodger Stadium, the 24-year-old was in the Angels’ starting lineup, batting fourth against veteran Cleveland starter Ralph Terry. In his first at-bat, in the second inning, Shockley reached on an infield single, his only hit in four at-bats, and after the game he told sportswriters, “I wasn’t as shaky in my debut here as I was last year when the Phillies called me up.” Yet within a few short months his season, and career, were over.

By April 30, Shockley, playing only against right-handers, was batting just .120 (3-for-25). Meanwhile, Adcock was sizzling, batting .357. Adcock, however, mentored the youngster, offering Shockley “tips on pitchers and what pitches to look for.” Shockley struggled with his batting average started showing some power. On May 2, in a doubleheader at Kansas City against the Athletics, the slugger, batting fourth in each game, doubled twice and drove in three runs. Then two days later, at home before a crowd of 4,888, Shockley, who entered the game just 6-for-40, produced the singular moment of his career: Facing Boston starter Dave Morehead in the bottom of the fifth with the bases loaded, Shockley “forced a fastball into the right-field pavilion” for his first grand slam and second career home run, in an eventual 7-1 Angels win. On May 13, in Minnesota, he then hit a two-run homer off Camilo Pascual, and by May 17 was batting .159.

Three weeks later, however, it all came to an end. Shockley had this explanation in a 2009 interview:

“In June, when I approached Rigney and asked if I was going to stay with the Angels, he said yes. So I moved my wife and baby out to California. Then (on June 12) they asked me to go to the minors instead, to Seattle. I wasn’t going to have my wife drive to Seattle. She didn’t know anything about the city.”

Instead, Shockley went home, and on July 1 the Angels placed him on the disqualified list for failure to join Seattle. His baseball career was over.

In truth, Shockley said of his decision,”I never really adjusted to the big-league atmosphere. I wasn’t making any money then, only $1,000 a month. It cost me $600 to rent an apartment; I was using up my bonus money; the major-league minimum was only $6,000. … So, I quit. I took my family over baseball.”

Forty-four years later, Shockley said he has no regrets. “Do I think I could have played in the big leagues? Sure, I think I would have done well.” Nevertheless, his life beyond baseball has been fulfilling. After refusing assignment to Seattle, Shockley retired from the game and returned to Georgetown, where he worked in the construction industry, retiring in 2005. Mary Lou died in 1994. In 2002 Shockley married his new wife, Susan, a schoolteacher, and, he said in 2009, “We’re doing just fine.”

He retained a love for baseball. In 1981, Shockley received “the biggest thrill I ever had” in the sport when he coached his son’s team in the Eastern Regional Tournament Senior Little League from Georgetown (Costen, Jr. played second base) to a championship in Gary, Indiana, over a team from California. He also enjoys watching his grandchildren. Between his two sons, Shockley has six grandchildren — four boys and two girls. All the boys play baseball at some level, and Shockley watches them every chance he gets. Moreover, both Shockley’s brother, Joe, and nephew, Scott, starred on the University of Delaware baseball team.

His brief career was not without recognition. In November 1973, the Salisbury Times, writing about Shockley’s brother, Joe, then “a young, promising quarterback at Sussex Central High School, in Georgetown,” wrote, “Costen is a road foreman currently involved with the headaches of the new US 13 Bypass around Salisbury.”

Near the eastern end of that bypass is the Eastern Shore Baseball Hall of Fame Museum. Shockley was inducted into the Hall in 1995. In 1997, he was inducted into the Delaware High School Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame; and in 1998, Shockley was inducted into the Delaware Sports Museum Hall of Fame, located at Frawley Stadium in Wilmington, Delaware. He is also a member of the Arkansas Travelers Hall of Fame.

Undoubtedly, Costen Shockley made his family proud.

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Interviews

Telephone interview with Costen Shockley by the author on August 5, 2009. Unless otherwise attributed, all of Shockley’s quotations are from this interview.

Costen Shockley player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Newspapers

Cumberland Times, Maryland, The Independent, Pasadena, California, Jefferson City Post Tribune, Maryland, Salisbury Times, Maryland, The Star-News, Pasadena, California. Titusville Herald, Pennsylvania

Websites

ArkansasOnline, Baseball-reference.com, Bluehens.com

Full Name

John Costen Shockley

Born

February 8, 1942 at Georgetown, DE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.