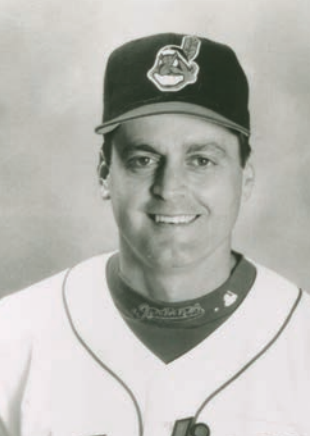

Jim Poole

It was October 28, 1995. In Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium, the Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves squared off in Game Six of the World Series, with the Braves leading, three games to two.

It was October 28, 1995. In Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium, the Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves squared off in Game Six of the World Series, with the Braves leading, three games to two.

Through 5½ innings the teams were scoreless. As the contest entered the bottom of the sixth inning, 29-year-old left-handed pitcher Jim Poole took the mound for Cleveland and prepared to face the Braves’ fifth, sixth, and seventh hitters. That Poole was in the game in the sixth was due to a move for which Indians manager Mike Hargrove would afterward receive a barrage of criticism. With two outs in the bottom of the previous inning, Cleveland starter Dennis Martinez allowed a walk and a single; so with left-handed slugger Fred McGriff due up for Atlanta, Hargrove replaced Martinez with Poole, his situational lefty. As he had done so often against left-handed hitters during the regular season, Poole fanned McGriff, on three pitches, and preserved the scoreless game.

With no Cleveland runs on the board, perhaps that should have been it for Poole. So impressed had Hargrove been with the relative ease with which Poole had dispatched McGriff, however, and with another left-handed hitter due to lead off the bottom of the sixth for Atlanta, instead of making another pitching change Hargrove left Poole in the lineup, batting ninth. (In that spot, he he would bat second for Cleveland in the top of the sixth inning. If Poole came to the plate, it would be his first major-league at-bat.) Hargrove would take his chances with Poole at bat if it meant having his clutch southpaw on the mound in a pressure situation.

If dreaming of playing in a World Series is a part of many boys’ childhoods, it surely must have seemed a remote one for young James Richard Poole. Born April 28, 1966, in Rochester, New York, young Poole moved with his parents, Rick and Judy, from Rochester to the Philadelphia area. At LaSalle College High School (Class of 1984), in Wyndmoor, 15 miles north of the city, Poole by all appearances Poole was an undistinguished kid playing on mediocre-to-poor teams.

As Poole recalled of those years, “Most of my coaches didn’t let me pitch.”1 His high-school record was just 2-16, “and,” he added, “I had to go 10 innings for one of those wins.”2 Such futility couldn’t have given Poole much expectation for a career in the sport; and indeed, many years later, having accomplished an 11-year major-league career, he said, “I have gone far beyond any expectations I set when I was a kid.”3

Poole’s fortunes changed dramatically when he attended college. Apparently intent on earning an electrical-engineering degree, he enrolled at Georgia Tech University. At the same time, though, he appears to have wanted to extend his baseball career, for, as he later explained, “I recruited myself by writing the baseball coach letters. They kept me on the team so I could help the freshman grade-point average.”4 Soon he had excelled far beyond that rather humble status.

By the end of his senior year, Poole was one of the best college relievers in the country. From 1985 to 1988, he played on four straight Atlantic Coast Conference championship teams, and was a pivotal contributor throughout, primarily in his final two seasons, during which he saved 19 games and was each year named to the All-ACC team. When Poole retired from the major leagues in 2000, he stood first in Georgia Tech history, with 22 career saves.

By his junior season, 1987, Poole had drawn the attention of major-league scouts. In June he was selected by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 34th round of the amateur draft. Wanting to complete his electrical-engineering degree, Poole declined the chance to turn pro, and instead returned to school. The following season the Dodgers again drafted him, this time in the ninth round. So, armed with his degree, Poole began his professional baseball career.

Speaking years later about his mindset on the mound in tough situations, Poole recalled one particular collegiate day in 1985, his freshman season. “It was a game that changed my course in baseball. What happened that day was bad, but it actually turned everything around for me. Tech had qualified for the NCAA Regionals and we had a three-game series with Mississippi State as kind of a warm-up. Coach (Jim) Morris decided to use me to determine if I was ready to help the team in the regionals.

“I went out there scared to death and fell to pieces against a team that had four future major leaguers (Will Clark, Bobby Thigpen, Rafael Palmeiro, and Jeff Brantley). I walked two batters and never got anyone out. Needless to say, I didn’t make the squad for the regionals.

“After that game I made a vow that win or lose, from then on I would give the best I had. I made up my mind to relish a situation such as that rather than let the pressure overcome me. Actually, I used that game as motivation throughout my career at Tech and in the majors.”5

It didn’t take long for Poole to establish himself as a prospect. Over his first two minor-league seasons, at Vero Beach, in the Class-A Florida State League (with one game also at Bakersfield in the Class-A California League in 1989), he proved he was already a polished reliever. In 1989, he pitched in a league-leading 60 games and was dominant, leading the club in wins (11) and strikeouts (93 in 78⅓ innings), posting a 1.61 ERA, and finishing second in the league with 19 saves. That performance earned Poole a promotion to San Antonio of the Double-A Texas League, where he was again effective, saving 16 games with 77 strikeouts in 63⅔ innings. Midway through that 1990 season, the Dodgers called.

On June 14, 1990, with the San Diego Padres visiting Los Angeles the next day to begin a three-game series, the Dodgers’ two left-handed relievers were both on the disabled list, leaving the team without a left-hander in their bullpen. That day, Poole was told by his San Antonio manager that he was to immediately join the Dodgers in LA.

“I thought I’d been traded,” Poole stated at the time. “It was the last thing I expected. It felt great. It’s every young boy’s dream. But it took me completely by surprise.”6

“I guess they need someone to come in for one batter and get a left-hander out now. I was just lucky enough to get the break.”7 That was undoubtedly so; although if he could have known who his first batter was to be, maybe Poole’s outlook would have been different.

The Padres and Dodgers went to the 11th inning with the scored tied, 1-1. To begin the 11th, manager Tommy Lasorda sent Poole to the mound. For San Diego, future Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn led off. If Poole was nervous, he never confessed as much. In short order, Gwynn was called out on strikes, and Lasorda immediately removed Poole from the game.

Six years later Poole recalled of his debut, “That was unbelievable. As a kid, you dream of striking out a batting king in your first big-league game. I couldn’t believe it. I could barely sit down afterward in the clubhouse.”8

It was to be the highlight of Poole’s first major-league season. Poole made six more appearances before he was returned to San Antonio on July 1. When the rosters expanded on September 1, he was back with the Dodgers and pitched nine more times, including a game at Houston, on September 26, when he allowed his first major-league home run, to Franklin Stubbs, in a 10-1 loss. In all, Poole worked 10⅔ innings in 16 games, registering neither a decision nor save. In December the Dodgers designated Poole for assignment, and on December 30 traded him to the Texas Rangers for two minor leaguers. It wouldn’t be the last time in his career that Poole changed teams.

The year 1991 began for Poole a somewhat nomadic existence. Over the next 10 years, he wore seven different major-league uniforms. After attending major-league camp with Texas, Poole began the season with Triple-A Oklahoma City, in the American Association. There, he registered three saves and averaged over a strikeout per inning. When the Rangers placed pitcher Brad Arnsberg on the disabled list on May 7, Poole was recalled. It was to be a brief engagement, however. After just five appearances, including his first major-league save, registered at home on May 18 versus Roger Clemens and the Red Sox, on May 25 the Rangers placed Poole on waivers, and he was quickly claimed by the pitching-challenged Baltimore Orioles. Poole remained with Baltimore for four seasons, and pitched in 123 games, his second-most with a single organization.

At Rochester, the Orioles’ Triple-A affiliate in the International League, Poole again drew notice, saving nine games with 29 strikeouts in 29 innings. By July 31, 1991, the 40-60 Orioles made wholesale pitching changes, demoting three to Rochester and recalling three, including their top prospect, Mike Mussina, as well as Poole. Over the remainder of the 1991 season, Poole proved a valuable asset in Baltimore’s bullpen, as he tossed 36 innings in 24 games and posted three wins, an ERA of 2.00, and 34 strikeouts. For a while, at least, Poole seemed to have found a home.

The following season, 1992, Poole experienced his first bout with an injury, which severely limited his major-league activity. Bothered at the beginning of the season by left shoulder tendinitis, Poole began the year on a rehab assignment with the Hagerstown (Maryland) Suns in the Double-A Eastern League. Wanting to improve the strength in Poole’s arm, the Suns gave him the first three starts of his professional career. Soon he went to Rochester, and, still bothered by his injury, for the first time struggled on the mound; his final numbers were 1-6 and a 5.31 ERA in 42⅓ innings, although he did save 10 games. Despite that performance, though, when the rosters expanded on September 1 and Poole was recalled to Baltimore, he pitched in only six games, for a total of 3⅓ innings. He went home hopeful that the injury was behind him.

Much to the Orioles’ relief, the next year proved that Poole’s injury was, in fact, healed. The 1993 season was arguably his best in the majors. That “was a breakthrough year for me,” Poole said. “I got off to a good start with 12 straight scoreless outings. That gave me confidence, and also gave the team confidence in me.”9 Indeed, only twice in his career did Poole make more appearances than his 55 that season, and never did he exceed the 50⅓ innings worked (although he twice later tied that mark). As Baltimore, playing its second season in Camden Yards, improved to third place under manager Johnny Oates, Poole came in time and again to face the opposition’s toughest left-handed hitters, and invariably got the best of the battle. With a 2.15 ERA, Poole’s batting average versus right-handed hitters was just .174, and against left-handers, .177. Poole also got two of his four major-league saves in 1993.

That was Poole’s final quality season for the Orioles. The next year, 1994, as Baltimore finished second in a strike-shortened campaign, Poole’s performance significantly deteriorated: In 38 games, covering just 20⅓ innings, he allowed 32 hits and his ERA ballooned to 6.64. On December 23 Poole became a free agent, and he ended 1994 unemployed. He wouldn’t remain that way for long, though; and the following season Poole found himself on baseball’s biggest stage.

On March 18, 1995, Poole signed a minor-league contract with the Cleveland Indians. With the players strike winding down, he began the season with the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons. When the strike ended, Poole joined the Indians at spring training. Given his poor 1994 performance in Baltimore, he had much to prove. Displaying a quality curveball, which had eluded him the previous year, Poole pitched his way onto the team and opened the season in the bullpen. In his first appearance, on April 28 at Texas, he entered a 9-9 tie game in the bottom of the sixth inning and gave up a solo home run to Mickey Tettleton in the eighth. Poole took the loss. But on May 7, at home versus the Minnesota Twins, in a 17-inning Cleveland victory, Poole threw the final four innings of another 10-9 slugfest, allowing just one hit while striking out three, to earn his first Cleveland win. That performance established his place on the staff and Poole recorded a solid season, finishing 3-3 with a 3.75 ERA in 50⅓ innings. Most impressive were his .217 batting average against and .156 average against with runners in scoring position. Clearly, Poole had righted his ship.

For the Indians, 1995 was their first World Series since 1954. For Poole, it was his first postseason. He saw action in every series. As the Indians swept the Red Sox in the American League Division Series, Poole appeared in Game One, at Cleveland’s Jacobs Field. Beginning the 11th inning of a 3-3 tie, he allowed a home run to Boston’s Tim Naehring to fall behind, 4-3, but Tony Peña’s home run in the bottom of the 13th won the game for Cleveland. Against the Seattle Mariners in Game Four of the Championship Series, Poole entered in the top of the eighth inning at home with the Indians ahead 7-0 and retired all three men he faced, striking out two.

Then came the World Series.

After Atlanta won Game One, the second game took place on October 22, in Atlanta. Entering the sixth inning, the game was tied 2-2. However, after Cleveland was held scoreless in the top of the sixth, Indians starter Dennis Martinez allowed a two-run homer in the bottom of the inning to give Atlanta the lead. In the top of the seventh, the Indians got one run back, and in the bottom of the inning Poole came on to start the inning against the heart of the Braves’ order. In succession, he retired sluggers Chipper Jones, Fred McGriff, and David Justice to keep the score at 4-3, but Cleveland couldn’t score, and that’s where the game ended.

Poole remained in the bullpen as the Indians took two of the next three games in Cleveland, and as the Series returned to Atlanta, the Braves held their 3-games-to-2 lead. For Poole, Game Six would be one of those games that will forever live in infamy.

Having struck out Fred McGriff swinging to end the bottom of the fifth inning, Poole was the second batter scheduled in the top of the sixth. Entering the inning, Braves starter Tom Glavine had tossed a no-hitter. That lasted one batter. Hitting eighth and leading off the inning, Indians catcher Tony Peña singled for what would be the only hit allowed by Glavine that night. That brought Poole to the plate.

Allowing Poole to hit was, of course, a questionable move in a tie contest, one for which Hargrove was afterward lambasted by the press. In compiling his Series roster, Hargrove had elected to keep on his bench two utilitymen perfectly suited for such a situation, Alvaro Espinoza and Ruben Amaro, both excellent bunters. (Amaro had been added to the roster at the expense of future Hall of Famer Dave Winfield.) Moreover, in the bullpen Hargrove had two left-handed pitchers remaining, Alan Embree and Paul Assenmacher, either of whom could be used to face the Braves’ left-handed hitters. In any event, though, Hargrove elected to send Poole to the plate with instructions to bunt. Poole failed on three tries, the last one a foul popup to the first baseman.

After Poole’s failed bunt, Glavine retired the next two batters, on a fielder’s choice and, after a stolen base, a foul popup. So Poole went to the mound to face the Braves in the bottom of the sixth.

Leading off for Atlanta was left-handed-hitting David Justice, whom Poole had retired in Game Two on a long fly ball to right field. Now, Poole threw two pitches outside to Justice, a ball and a strike. On the third pitch, Poole attempted to go low and outside again with a fastball, and the ball tailed inside. Turning on it, Justice drove the ball over the right-field wall to stake the Braves to a 1-0 lead. It was only the third home run Poole allowed all season to a left-hander – he had earlier allowed home runs to Baltimore’s Harold Baines and California’s J.T. Snow – and it was a back-breaker.

Poole retired the side, but the damage was done. In the bottom of the seventh, Ken Hill relieved Poole, and four pitchers followed, including the two left-handers. Atlanta never scored again but neither did Cleveland, and Justice’s home run stood as the only run of the game. Atlanta won the Series in six games.

Having failed both at the plate and on the mound, Poole could have avoided sportswriters after the game by escaping to the sanctity of the trainer’s room. Instead, he stood at his locker, fielded every question, and accepted blame for the defeat, reasoning, “It isn’t a pleasant part of the job, but you are paid to perform and paid to talk about your performance.”10

Regarding his bunt attempts, Poole said, “It should not be that big a deal to lay down a four-seam fastball. That was my job.”11

And as to whether his at-bat impacted his pitching: “I went up there fully confident that I could sacrifice Tony Pena to second. I promise you I didn’t take my failure to do that out to the mound with me, even though Justice was the first man I faced.”12

Finally, Poole also proved that he hadn’t lost his sense of humor when he quipped, “Justice had no business looking inside after everything I threw was away.”13

He had kept it all in perspective.

The following spring, columnist Bill Livingston of the Cleveland Plain Dealer had nothing but praise for Poole’s attitude with the press that night. Although Justice’s home run was “the most deflating home run yielded by an Indians pitcher since Bob Lemon’s to Dusty Rhodes in the 10th inning of the 1954 World Series. … the test of the inner person in any sport comes away from the champagne and celebrations. Poole came up big in that measure of a man. He would not let himself be diminished by defeat.” Besides, Livingston continued, “Poole made one bad pitch. But when any pitching staff gives up only one run, it has done its job. The Tribe’s silent bats were the reason the World Series ended that night.”14

It was a sentiment Poole had undoubtedly considered.

As the 1996 season approached, Poole, who that night had assured the press that “I won’t dwell on it. I will try to use this on days during the winter in which I don’t want to work out, to push myself. And it will remind me that you have to make every pitch better because one pitch can make a season,”15 likewise assured them, “I know that we will have plenty of motivation this season, after we had to watch the Braves celebrate.”16

“The World Series “was all a fantasy,” he continued, “until the last pitch. I suppose I’ll hear about it out of frustration if I get off to a bad start.”17 As it turned out, he had only half a season to find out.

By July 9, Poole had appeared in 32 games for Cleveland and fared very well, amassing a 4-0 record and 3.04 ERA in 26⅔ innings. That day, though, Poole was traded to the San Francisco Giants for outfielder-first baseman Mark Carreon. With starting first baseman Julio Franco nursing a strained hamstring, and backup Herbert Perry undergoing knee surgery, Cleveland sought a right-handed hitter to fill in at first and come off the bench. Carreon filled that need.

“Mark gives us greater flexibility,” manager Hargrove said. “We are not excited to lose a pitcher like Jim Poole, but you can’t have your cake and eat it too.”18

For the remainder of that season, Poole served as the Giants’ primary left-handed specialist (35 games) and finished the season strongly, 2-1 with a 2.66 ERA in 23⅔ innings pitched. (He did not play in the Giants’ Division Series loss to Florida.) But it was to be his last impressive showing. In 1997 Poole spent the entire year with San Francisco but endured a ghastly 7.11 ERA in a career high 63 games, caused primarily by 13 earned runs allowed in his final five appearances. By July 1998, Poole’s 5.29 ERA had convinced the Giants that the left-hander was no longer effective, and on July 15, he was released.

Poole had one more moment in the spotlight, however. Perhaps feeling they could rekindle his prior success, the following week the Indians signed him to a minor-league contract and sent him to Buffalo, where he was lights-out for 10⅓ innings (16 strikeouts and a 0.87 ERA). Assured by their first-place standing of another postseason appearance, Cleveland promoted Poole to their roster in time for him to be postseason-eligible, and that fall he pitched twice in the Tribe’s Division Series win over Boston and four times in the Championship Series loss to the Yankees.

In December 1998, Poole returned to Philadelphia, signing a one-year, $500,000 contract with the Phillies. Having watched Poole twice retire tough left-handed Yankee Paul O’Neill during the 1998 ALCS, Phillies manager Terry Francona was convinced Poole could fill the specialist role in his bullpen. For his part, Poole said, “The Phillies were always my first love. My parents are just as excited about this as me.”19 After 51 appearances, though, Poole was released in August, and once again signed by the Indians, where he once again made the playoff roster, but this time did not participate during the Division Sereies loss to Boston.

The 2000 season was Poole’s last, and was not without controversy. On December 20, 1999, he agreed to a minor-league contract with the Detroit Tigers and in the spring made the club. On April 22 in Chicago, the Tigers and White Sox played a scrappy 14-6 contest, won by the White Sox, which featured a brawl that resulted in 16 members of the two teams being suspended for a total of 82 games. Although Poole, who worked two-thirds of an inning, didn’t participate in the on-field fighting, he did return to the field after leaving the game, for which he was fined $500. On May 17, saddled with a 7.27 ERA, Poole was released by Detroit, and subsequently signed by the Montreal Expos to shore up their injury-depleted bullpen. In two innings Poole allowed eight hits and six runs before the Expos released him and on June 9, perhaps fittingly, he was signed a final time by the Indians and sent to Buffalo, where he pitched the final 10 games of his career.

Over his career, Poole earned over $4 million. While a student at Georgia Tech he had met Kimberly, his future wife. In 1996, Poole told a reporter: “We bought a house in Georgia, just outside of Atlanta in Alpharetta. We decided it was time to put down some roots, especially for our two boys. We had lived for the past four years near Baltimore. My wife has put her career on hold for me. She has a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering, and a master’s degree in finance. Now, it will be her chance. I’ll follow her.”20

In his mid-50s, Poole was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. He died at the age of 57 on October 6, 2023.

For the young man who won two high-school games, it had been quite a ride. In 11 years he pitched in 431 games for eight teams and won 22 games. Yet he’d always be remembered for one inside fastball on a sultry night in Atlanta.

Sources

Jim Poole player file from National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Baseball-reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

Ramblinwreck.com/sport.

NewsPaperArchive.com.

Notes

1 Sports Collectors Digest, June 21, 1996.

2 Jim Salisbury, “New southpaw, dogged, lucky”, Philadelphia Inquirer, February 22, 1999: D-1.

3 Sports Collectors Digest, June 21, 1996.

4 Salisbury.

5 ramblinwreck.com/sports/m-basebl/spec-rel/100401aaa.html.

6 National Sports Daily, June 15, 1990.

7 Ibid.

8 Sports Collectors Digest, June 21, 1996.

9 Ibid. It was actually 12⅔ scoreless innings pitched by Poole.

10 Bill Livingston, “Poole’s One Pitch Didn’t Lose Series”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 13, 1996: 1D.

11 New York Post, October 30, 1995.

12 Livingston.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 New York Post, October 30, 1995.

16 Livingston.

17 Ibid.

18 USA Today, July 10, 1996.

19 Salisbury: D-6.

20 Sports Collectors Digest, June 21, 1996.

Full Name

James Richard Poole

Born

April 28, 1966 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

October 6, 2023 at Alpharetta, GA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.