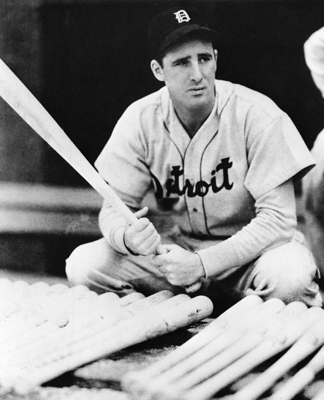

Hank Greenberg

Any list of the greatest sluggers ever to wear a Detroit Tigers uniform has to include Hank Greenberg. Despite losing four years of his physical prime to World War II, he still put together a 13-year career (all but one with the Tigers) that included 331 home runs with 1,276 RBIs. A .313 hitter, he also drew a high number of walks, contributing to his .412 lifetime on-base percentage. Add to that a slugging average of .605, and his career OPS (on-base plus slugging) is an exceptional 1.017, a figure topped by only four other players at the time of his retirement (Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx). Greenberg made a serious run at Babe Ruth’s single-season home-run mark in 1938. His Tigers teams went to four World Series, winning two of them. He did all this while enduring anti-Semitic slurs that were part and parcel of baseball at the time.

His parents were both Jewish immigrants from Romania. David Greenberg and Sarah Schwartz met in America, and married in 1906. Henry Benjamin Greenberg, who would later be known throughout baseball as “Hammerin’ Hank,” was born on January 1, 1911. He was originally supposed to be named Hyman, but apparently the man filling out his birth certificate had never heard of such a name. Henry had an older brother, Ben, an older sister, Lillian, and a younger brother, Joe.

In time, David Greenberg moved his family from their Greenwich Village home to more spacious living quarters in the Bronx, across the street from the municipal baseball fields of Crotona Park. It was there that the young Henry Greenberg fell in love with the game that was to make up his livelihood. He spent hours hitting the ball in the park, getting the neighborhood kids to shag for him.

Greenberg was a multisport star at James Monroe High, and his best sport wasn’t baseball, but basketball. He also excelled at soccer and track and field, and while he wasn’t a particular fan of football, he tried out nonetheless just to prove that he could play it, and wound up catching a touchdown pass in the season’s final game.

The Yankees, along with the Washington Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates, were hot on the prospect’s trail. Yankees scout Paul Krichell even took Greenberg to a game at The Stadium. From his front-row box seat, Greenberg was impressed by the power of Lou Gehrig, but Krichell leaned over to the teenager and whispered, “He’s all washed up. In a few years, you’ll be the Yankee first baseman.”1

It didn’t materialize that way, as Tigers scout Jean Dubuc got Greenberg to sign with Detroit in September of 1929.

Greenberg’s first year in professional baseball was with the Raleigh (North Carolina) Capitals of the Class-C Piedmont League in 1930. Only 19, Greenberg put in a very good season in Class-C ball, hitting .314 with 19 homers in 122 games as a first baseman. He also spent part of the summer with the Hartford (Connecticut) Senators of the Class-A Eastern League, getting into 17 games. Meanwhile the second-division Tigers wanted to get a look at the powerful kid, and called Greenberg up for the season’s final three weeks. He got into one game, on September 14 at Navin Field against the Yankees, popping up to second base.

It had been a lonely first year for Greenberg, as he was the victim of Jew-baiting, even from some of his own teammates. During batting practice one afternoon, pitcher Phil Page reportedly called Greenberg a “goddamn Jew” after Greenberg had lined a pitch that struck Page in the knee. But other teammates, like Schoolboy Rowe and Billy Rogell, were an encouragement to the youngster. “Go out and outplay the bastards,” Rogell told him.2

Solid seasons for the Evansville Hubs (Class B) and the Beaumont Exporters (Class A) the next two seasons led to Greenberg’s finally making the Tigers for good in 1933. Under manager Bucky Harris, Detroit sputtered along at 75-79, good for fifth place in the American League. Greenberg’s first big-league home run came in Detroit, off Washington’s Earl Whitehill, on May 6. He was beginning to find a consistent stroke, hitting .301 with 12 home runs and 87 RBIs. He was also filling out physically, at 6-feet-4 and 215 pounds of muscle.

The next season, 1934, was Greenberg’s (and the Tigers’) breakthrough season. Under new player-manager Mickey Cochrane, Detroit won its first American League pennant since 1909. Greenberg, with a league-topping 63 doubles, 26 home runs, 139 RBIs, and .339 batting average, was now a feared slugger in a lineup that also featured Charlie Gehringer and Goose Goslin.

That year Greenberg was first faced with the dilemma of whether or not to play on Rosh Hashanah, which fell on September 10. In the past, Greenberg had never hesitated to play baseball on the Sabbath, but the High Holy Days were another matter. In 1933 he had abstained from playing both on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. As the calendar turned to September 1934, the Tigers were in first place, but could feel the Yankees breathing down their necks. Many fans wanted Greenberg to make an exception and play on Rosh Hashanah.

After much reflection (even consulting a rabbi), Greenberg decided to play in the game that day. It was one of the defining moments of his career, as he homered twice, helping the Tigers win 2-1. Ten days later, with the pennant all but wrapped up, Greenberg declined to play on Yom Kippur. The popular nationally syndicated newspaper poet Edgar Guest penned an ode to Greenberg, ending with the lines: “We shall miss him on the infield and shall miss him at the bat, But he’s true to his religion — and I honor him for that!”3

Greenberg was the first to admit that he never strongly identified himself as a Jew. But every day opposing bench jockeys, and a certain element of abusive fans, never let him forget his Jewishness. “Sure, there was added pressure being Jewish,” he recalled. “How the hell could you get up to home plate every day and have some son of a bitch call you a Jew bastard and a kike and a sheenie and get on your ass without feeling the pressure. If the ballplayers weren’t doing it, the fans were. I used to get frustrated as hell. Sometimes I wanted to go up in the stands and beat the shit out of them.”4

In the World Series the Tigers squared off against the St. Louis Cardinals. It was a tough Series for Detroit, as they fell in seven games. Greenberg, however, boasted solid numbers, with nine hits, one home run, seven RBIs, and a .321 average.

With equal parts power at the plate and crowd appeal at the gate, Greenberg was one of the biggest sports stars in Detroit, in spite of all he had to endure. Affectionate nicknames abounded: “Greenie,” “King Kong,” The Big Moose,” “Lanky.” Baseball was experiencing a resurgence in the Motor City, and Greenberg was leading the way.

The Tigers finally won their first World Series in 1935, although they did it without the services of their star first baseman. Greenberg led the league in home runs (36) and RBIs (170), but he injured his wrist sliding into home plate in Game Two of the Series, and played no more. Detroit overcame the loss, however, to defeat the Chicago Cubs in six games.

Any chances the Tigers had of reaching the World Series again in 1936 went down the drain when Greenberg reinjured his wrist early in the season, and Cochrane, the heart and soul of the club, suffered a nervous breakdown. But Greenberg had a fine comeback in 1937, as he banged 40 home runs and knocked in 183 runs, coming within two of Lou Gehrig’s American League mark of 185. (Hack Wilson holds the major-league record with 191.)

It was 1938, however, that truly put Greenberg in the national consciousness. All summer long he chased Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record of 60. After a two-homer game in the second half of a doubleheader at St. Louis on September 27, Greenberg entered the final five games needing only two to tie the Babe.

The pressure had been mounting, and Greenberg was both physically and mentally spent. He didn’t hit another home run, finishing at 58. The final game of the season was played in Cleveland’s cavernous Municipal Stadium. He almost hit one out, but instead it banged off the fence in faraway left-center field. As twilight set in, umpire George Moriarty reluctantly called the game because of darkness. Turning to Hank, he said, “I’m sorry, Hank, this is as far as I can go.” An exhausted Greenberg replied, “That’s all right, George, this is as far as I can go too.”5

Greenberg thrived despite the raging anti-Semitism that surrounded him at times. “It was 1938 and I was now making good as a ballplayer. Nobody expected war, least of all the ballplayers. I didn’t pay much attention to Hitler at first or any of the political goings-on at the time. I was too stupid to read the front pages, and I just went ahead and played. Of course, as time went by, I came to feel that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler.”6

Another fine season ensued in 1939, and, despite a switch to the outfield (to accommodate new first baseman Rudy York), Greenberg continued to put up spectacular numbers in 1940. Detroit reached the World Series again, falling in seven games, this time to the Cincinnati Reds. Greenberg slugged 41 home runs, drove in 150 runs, and batted .340 for

the year.

And then, like so many other diamond stars of the time, Greenberg was off to war. Whether or not he would be drafted was an open question for several months, mainly because of his flat feet. Finally told that he would have to report for duty on May 7, 1941, Greenberg began the season with Detroit. In his final game before entering the service, he rose to the occasion by slamming two home runs as the Tigers beat New York 7-4 at the recently renamed Briggs Stadium on May 6.

The following morning, Greenberg was inducted into the Army at Fort Custer, Michigan (Fifth Division, Second Infantry Anti-Tank Company). About three months after he went into the service, Congress passed a law dictating that men over 28 years old were not to be drafted. On December 5, 1941, 30-year-old Sergeant Greenberg was given his discharge. He headed home to Detroit to begin getting ready for the 1942 season.

But things changed only a few days later, on December 7, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Greenberg decided his country still needed him, and enlisted in the Air Corps. With all the uncertainty in the world, he wasn’t sure when he would ever put on a big-league uniform again. “We are in trouble and there is only one thing to do — return to service,” he said. “I have not been called back. I am going back of my own accord. Baseball is out the window as far as I’m concerned. I don’t know if I’ll ever return to baseball.”7

Greenberg was sent to Officer Candidate School, and commissioned as a first lieutenant on graduation. He later spent time in the China-Burma-India Theater. He received his discharge — again — on June 14, 1945.

For Greenberg, his time spent defending his country in World War II was life-changing. By the time he returned to the States, he realized that there were more important things in life than baseball. He had matured as a man. “It was a long hitch and it was a wonderful experience,” he wrote later. “I can’t say it was enjoyable insofar as we were deprived of our liberties, but considering that so many men had suffered much greater hardships than I had, and quite a few of them had lost their lives, I guess I was just lucky to come back in one piece.”8

Still, he wasn’t through playing yet. He rejoined a Tigers team that was in first place, battling for the pennant with the Yankees. In his first game back, on July 1, 1945, before a capacity crowd at Briggs Stadium, he hit a home run to cap a 9-5 Tigers win against Philadelphia.

Greenberg’s signature moment as a Tiger, however, came on September 30, the final contest of the 1945 campaign, when he hit a ninth-inning grand slam in the rain at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, to win the pennant for Detroit. Rounding the bases, even Greenberg couldn’t believe it. “I wasn’t sure whether I was awake or dreaming.”9

By virtue of his memorable poke, the Tigers had the honor of facing the Chicago Cubs in the Series. In a seven-game duel, Detroit won its second World Series title. Greenberg hit the team’s only two home runs, and paced the Tigers attack with seven RBIs.

The following season was a mixed bag for Greenberg. While he led the league in home runs with 44, and RBIs with 127, he’d also hit a career-low .277. At age 35, the Tigers felt that his better days were behind him. Greenberg couldn’t argue the point, as he spent much of the summer on the trainer’s table tending to various aches and pains. “I feel I’m on borrowed time. I don’t have the old beans anymore out there, and I’m not the hitter I used to be,” he said.10

On January 18, 1947, he was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates for $75,000.

Greenberg contemplated retiring, figuring he was getting too old for the ballplayer’s life. And after all, wasn’t Forbes Field, the Pirates’ home, a death valley for right-handed hitters? But the Pirates agreed to pull in the fences in order to lure Greenberg, naming the section “Greenberg Gardens.” They also offered to make him the first $100,000-a-year player in the game’s history. Throughout his tenure with the Tigers, Greenberg was a tough negotiator when it came time to talk salary, so the Pirates’ overtures were much appreciated.

The biggest beneficiary of Greenberg’s move to the National League was young Pirates slugger Ralph Kiner. Kiner had led the circuit in home runs as a rookie, but he was still a raw talent, undisciplined at the plate. Upon joining the Pirates in spring training, Greenberg immediately took Kiner under his wing, teaching him the finer points of what it takes to be a consistent slugger in the major leagues. “He was the most astute student of hitting I ever knew,” Kiner remembered about Greenberg later.11 Kiner went on to a Hall of Fame career, with 369 home runs. “Hank was the biggest influence on my life,” he recalled. “The biggest thing Hank taught me was that hard work is the most important thing.”12

The 1947 season was Jackie Robinson’s first year in the big leagues, and the Brooklyn Dodgers came into Pittsburgh for a series in May. Greenberg gave some heartfelt advice to the young African American trailblazer. “Listen, I know it’s plenty tough. You’re a good ballplayer, however, and you’ll do all right. Just stay in there and fight back. Always remember to keep your head up.”13

As for Greenberg, he hit 25 home runs in 125 games in 1947, with an unspectacular .249 batting average. His league-leading 104 walks contributed to his fine .408 on-base percentage. The Pirates were awful, at 62-92. “At the end of the season that year he couldn’t wait to get out of Pittsburgh,” Kiner noted. “Not the city but the way the ballclub was being run. There was no direction for the players, and we were at the bottom of the National League.”14 Greenberg’s final hit in the major leagues was a home run on September 15 in Pittsburgh, off Philadelphia’s Charley Shanz.

After retiring as a player, Greenberg hooked up with his best friend in baseball, Bill Veeck, who at the time owned the Cleveland Indians. Greenberg became the team’s general manager, helping to put together the nucleus of the team that won 111 games, but lost the World Series in 1954. But his marriage to Caral Gimbel (whose family owned the New York department store of the same name) was turning sour. The two had been husband and wife since 1946, but their paths always seemed to diverge. Greenberg was a company man, interested in the business of baseball, while Caral appreciated art and music, and kept fine show horses. The marriage benefited both financially, but there didn’t seem to be much else there.

Baseball’s highest honor came to Greenberg in 1956, when he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, along with Joe Cronin, the Red Sox’ All-Star shortstop and manager. “I’ve had many thrills in baseball,” Greenberg told the Cooperstown crowd. “This, though, is the greatest. Today I have the same butterflies in my stomach that I used to have when I came to the plate with the bases full with Grove or Gomez or Ruffing pitching.”15

When Veeck sold his interest in the Indians and became the owner of the Chicago White Sox, Greenberg followed him, becoming a part-owner and vice president. But his marriage continued to have problems, and by 1959 he and Caral were divorced. Together, they had three children: Glenn (also known as “Little Hank”), Steve, and Alva, along with eight grandchildren.

Always an astute investor, Greenberg plunged into the stock market and made millions on Wall Street in the 1960s. He sold his stake in the White Sox (for a neat profit), left his Manhattan home for sunny Beverly Hills, and lived the life of Reilly. He married Mary Jo Tarola, a minor movie actress, in 1966.

In 1983 Greenberg made it back to Detroit for one of the few times since he’d been let go after the 1946 season. The occasion warranted it: The Tigers planned a ceremony at Tiger Stadium to retire his uniform number 5, along with Charlie Gehringer’s number 2. Both players were able to make it, smiling and waving to the large stadium crowd. It was the final time Greenberg put in an appearance at the site of his greatest glories as a player. “I am very proud,” he told the throng, “of the fact that my name and uniform number will be remembered as long as baseball is played in Detroit.”16

On September 4, 1986, Greenberg died after a lengthy battle with cancer. He is buried in Hillside Memorial Park in Los Angeles. Greenberg’s is the classic American success story: With hard work, brains, and a little good fortune, a man can overcome his humble beginnings to be the master of his own destiny. Shirley Povich, the longtime sports columnist for the Washington Post, once wrote: “He was the perfect standard-bearer for Jews. Hank was smart, he was proud, and he was big.”17

An updated version of this biography is included in the book “Detroit the Unconquerable: The 1935 World Champion Tigers” (SABR, 2014), edited by Scott Ferkovich. It also appeared in “Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians” (SABR, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho, and “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Notes

1 William Kashatus, Lou Gehrig: A Biography (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004), 50.

2 John Rosengren, Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes (New York: New American Library, 2013), 37.

3 Hank Greenberg with Ira Berkow, The Story of My Life (Chicago: Ivan Dee Publishers, 2001), 58.

4 Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993), 85.

5 Terry Foster, 100 Things Tigers Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 9.

6 Greenberg, 111.

7 Greenberg, 142.

8 Greenberg, 144.

9 Rosengren, 268.

10 Greenberg, 160.

11 Rosengren, 306.

12 Greenberg, 184.

13 Rosengren, 309.

14 Greenberg, 186.

15 Ira Berkow, Hank Greenberg: Hall of Fame Slugger (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2001), 85.

16 Associated Press, “Tigers Retire Numbers of Gehringer and Greenberg,” Daytona Beach Morning Journal, June 12, 1983.

17 Greenberg, xii.

Full Name

Henry Benjamin Greenberg

Born

January 1, 1911 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

September 4, 1986 at Beverly Hills, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.