April 15, 1947: Jackie Robinson makes historic debut with Brooklyn Dodgers

Jackie Robinson‘s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers was more than just the first step in righting a historical wrong. It was a crucial event in the history of the American civil rights movement, the importance of which went far beyond the insular world of baseball.

Jackie Robinson‘s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers was more than just the first step in righting a historical wrong. It was a crucial event in the history of the American civil rights movement, the importance of which went far beyond the insular world of baseball.

The Dodgers signed Robinson to a major-league contract just five days before the start of the 1947 season. Baseball people, especially those in Brooklyn, were still digesting the previous day’s news of manager Leo Durocher’s one-year suspension (for conduct detrimental to baseball), when the story broke of Robinson’s promotion from the Montreal Royals of the International League. He would be the first Black American to play in what were then designated the major leagues since catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker played for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association back in 1884.

Robinson had played second base for the Royals in 1946, but on orders from the Dodgers he had been working out at first base all spring. He played the position in Brooklyn’s final three exhibition games against the Yankees, and again two days later when the Dodgers opened the season at Ebbets Field against the Boston Braves. Rumors of a sellout may have discouraged some fans from attending, but whatever the reason, a crowd of only 26,623 saw Robinson’s debut, including “an estimated 14,000 black fans.”1

In his New York Times column the morning of the game, Arthur Daley credited the Dodgers for doing a “deft” job of paving the way for Robinson, but added, “Yet nothing can actually lighten that pressure, and Robbie realizes it full well. There is no way of disguising the fact that he is not an ordinary rookie and no amount of pretense can make it otherwise.”2

Robinson made the game’s first putout, receiving the throw from fellow rookie Spider Jorgensen on Dick Culler’s ground ball to third base. Dodgers left-hander Joe Hatten started the game for Brooklyn. Hatten gave up a single and a walk in the first, but no Braves scored.

Interim manager Clyde Sukeforth had Robinson batting second, so after Eddie Stanky grounded out, the rookie first baseman stepped in against Johnny Sain for his first National League at-bat. Sain, the NL’s winningest right-hander in 1946, retired him easily on a bouncer to third baseman Bob Elliott. After flying out to left fielder Danny Litwhiler in the third inning, Robinson appeared to have gotten his first Dodgers hit in the fifth. But shortstop Culler made an outstanding play on his ground ball and turned it into a well-executed 6-4-3 double play.

When he next batted, in the seventh, Brooklyn was trailing, 3–2. Stanky was on first, having opened the inning by drawing Sain’s fifth walk of the afternoon. It was an obvious bunt situation, and Robinson laid down a beauty, pushing the ball deftly up the right side. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’s Harold C. Burr wrote that Robinson had “sacrificed prettily.”3

Boston’s rookie first baseman, Earl Torgeson, fielded it, but with Robinson speeding down the line, he “made a hurried throw in an effort to get Robinson but hit him on the shoulder blade and the ball caromed into right field, allowing Jackie and the other runner to advance to second and third.”4 Pete Reiser’s double scored both runners and finished Sain. Stanky scored the tying run, and Robinson scored the go-ahead run – which by game’s end proved the winning run. Reiser later scored on Gene Hermanski’s fly ball off reliever Mort Cooper as the Dodgers won 5–3.

When the Dodgers took the field in the ninth inning, Robinson remained on the bench as veteran Howie Schultz took over at first base. Sukeforth had inserted Schultz as a defensive measure, but the Dodgers soon realized that Robinson needed no help. Schultz played in only one more game before Brooklyn sold him to the Phillies. Ed Stevens, the team’s other first baseman, played in just five games before he was sent back to the minors.

Hal Gregg, in relief of Hatten, got the win, and Hugh Casey got the first of his league-leading 18 saves.5 Sain bore the loss.

The popular Reiser, coming back from yet another injury, clearly had been the star of the game, and it was he, not Robinson, who was the focus of the story in the next day’s New York Times. Roscoe McGowen’s game account mentioned Robinson only in relation to his play, leaving columnist Arthur Daley to take note of his debut, which he called “quite uneventful.”6

He wrote that Robinson “makes no effort to push himself … and already has made a strong impression,” and then quoted Robinson as saying “I was nervous in the first play of my first game at Ebbets Field, but nothing has bothered me since.”7

In retrospect, it would be easy, and fashionable, to attribute the writers’ casual treatment of this history-making game to racism. It is perhaps more charitable, and accurate, to think that they handled it in this way because it took place at a time when baseball reporters believed that that’s what they were: baseball reporters, men who felt their sole duty was to report what took place on the field. Red Barber and Connie Desmond, the Dodgers’ radio broadcasters, did the same.

Rachel Robinson has written about this Opening Day game: “In 1947, as Jack took his place in the batter’s box in Ebbets Field, and Rickey watched from the owner’s box, the meaning of the moment for me seemed to transcend the winning of a ballgame. The possibility of social change seemed more concrete, and the need for it seemed more imperative. I believe that the single most important impact of Jack’s presence was that it enabled white baseball fans to root for a black man, thus encouraging more whites to realize that all our destinies were inextricably linked.”8

Robinson’s first base hit came in the season’s second game, on April 17 against the Braves. His first run batted in came against the New York Giants on April 18. By season’s end, he had hit for a .297 batting average (with a.383 on-base percentage), with a league-leading 29 stolen bases. He scored 125 runs, and drove in 48. His 28 sacrifice hits led both leagues. Robinson was the overwhelming choice in voting for Rookie of the Year, the first player ever accorded Rookie of the Year honors, at a time before voters honored a separate rookie in each league.

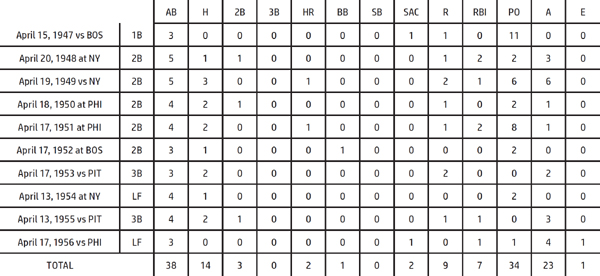

Jackie Robinson’s statistics on Opening Day

Compiled from data furnished by Dr. David W. Smith of Retrosheet.

Sources

This article is adapted from the author’s “Jackie Robinson on Opening Day, 1947-1956.” Joseph Dorinson, and Joram Warmund, eds. Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1998.)

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Related links

- Order SABR’s The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers, edited by Lyle Spatz, from the University of Nebraska Press website.

- SABR looks back at Jackie Robinson’s signing, debut

Notes

1 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 178.

2 Arthur Daley, “Play Ball!,” New York Times, April 15, 1947: 31.

3 Harold C. Burr, “‘Old’ Reiser, ‘New’ Hernanski Stars of Dodgers’ Opening Day Triumph,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 16, 1947: 19. Left fielder Hermanksi also had a run batted in.

4 Carl Rowan with Jackie Robinson, Wait Till Next Year (New York: Random House, 1960), 179.

5 Nobody had ever heard of “saves” in 1947, and Casey died never knowing that he had twice been the National League leader.

6 Arthur Daley, “Opening Day at Ebbets Field,” New York Times, April 16, 1947: 32.

7 “Opening Day at Ebbets Field.”

8 Rachel Robinson, with Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait (New York: Abrams, 2014), 66.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 5

Boston Braves 3

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.