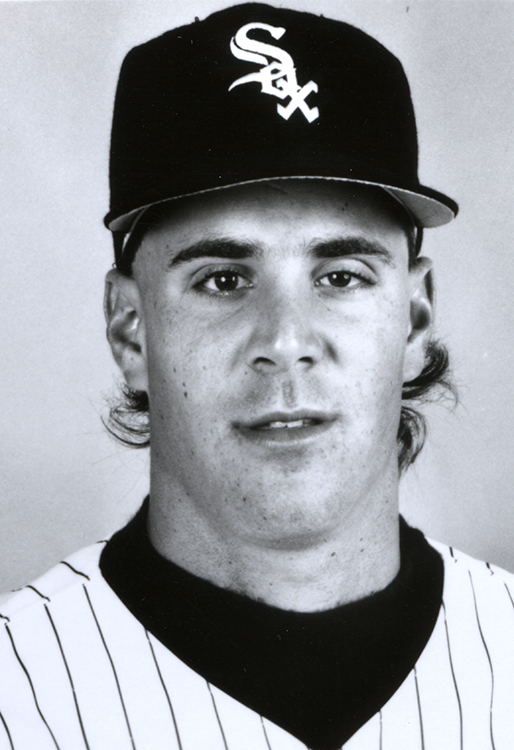

Scott Radinsky

“If you do stink it up today, you get to come out the next day and get another shot,” said Scott Radinsky. “That’s why I love being a reliever.”1 A hard-throwing left-hander, Radinsky was never afraid of failure, or a challenge. He made a big jump from Single A to the majors, debuting with the Chicago White Sox in 1990. After leading the staff in appearances for three straight seasons (1991-1993), he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment, and missed the entire 1994 season. Still weak when he returned to the South Siders a year later, he moved on to the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1996 and had three productive seasons. After Radinsky overcame cancer, two elbow operations, including Tommy John surgery, ended his career.

“If you do stink it up today, you get to come out the next day and get another shot,” said Scott Radinsky. “That’s why I love being a reliever.”1 A hard-throwing left-hander, Radinsky was never afraid of failure, or a challenge. He made a big jump from Single A to the majors, debuting with the Chicago White Sox in 1990. After leading the staff in appearances for three straight seasons (1991-1993), he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment, and missed the entire 1994 season. Still weak when he returned to the South Siders a year later, he moved on to the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1996 and had three productive seasons. After Radinsky overcame cancer, two elbow operations, including Tommy John surgery, ended his career.

Radinsky was more than just a dependable middle reliever and occasional closer who appeared in 557 big-league games in parts of 11 seasons. Described by Jeff Torborg, his first big-league skipper, as “a young, aggressive athlete,” and a “raw, strong, hard-throwing kid — a free spirit,” Radinsky was a brutally honest realist whose greatest passion might have been music, and he served as a frontman in several critically acclaimed Los Angeles-based bands, including Pulley, which was still performing as of 2016.2 “I’m a punk rocker,” he told Franz Lidz of Sports Illustrated in 1997.3 “I’m crazy about playing ball, but it’s just a sideline.”

Nobody ever confused Radinsky with a quiet, deferential company man. Throughout his playing career and as he transitioned into a respected minor- and major-league coach, Radinsky refused to conform to the expectations of the big money, corporate world of baseball, and proudly displayed his punk-rock ethos of anti-establishment, individuality, and anti-authoritarianism. Contrary to expectations, that attitude made Radinsky a well-liked player and trusted mentor to prospects. “I’m not a fan of the act you have to put on to be a big leaguer,” he continued in Sports Illustrated with refreshing detachment. “You play for some guy in a skybox. You’re like a puppet. You’ve got to do everything textbook, or you lose your job. You want to warm up, but the umpire stops you because he’s waiting for a TV commercial to end. What I like about punk is that it’s anticommercial. It’s pure.”4

Scott David Radinsky was born on March 3, 1968, in Glendale, California, about eight miles north of Los Angeles. His parents were Marshall L. Radinsky, a native of West Virginia, and Boston-born Barbara (Kornetsky) Radinsky. Scott had played some Little League ball, and was coached by his father, who worked for JME Signage, but he was more interested in skateboarding and the burgeoning Southern California punk-rock scene than in organized sports. “I was an angry, rebellious kid,” admitted Radinsky.5 By the age of 15 he co-founded the band Scared Straight, which released its first record in 1984.

Radinsky grew up a Dodgers fan, but didn’t follow major-league baseball too closely. As a member of the Simi Valley High School baseball team, Radinsky played the way he sang — full throttle with little discipline. He evolved from a disinterested first baseman as a sophomore on the junior-varsity squad to closer as a junior, and then as a senior burst on the scene with the force of a speeding, 90-second Minor Threat song as one of the region’s best starting pitchers. “Scott had absolutely no mechanics,” said his coach, Mike Scyphers. “He just got the ball and threw it.”6 At 6-feet 3 and weighing about 170 pounds (he’d add another 20 pounds in the course of his career), Radinsky (14-1, 0.72 ERA with 180 strikeouts in 100⅓ innings) attracted big-league scouts as Simi Valley was ranked the number-one high-school team in the country in 1986.7 On June 2 the White Sox selected the 18-year-old graduating senior in the third round with the 75th overall pick in the amateur draft. “Once I found out [professional baseball] was a reality,” Radinsky revealed about discovering that he was drafted, “I think the option of school was out the door. To get that opportunity was awesome. I wasn’t really familiar with the White Sox, but you learn pretty quick.”8

The teenage Radinsky commenced his professional baseball career in the Rookie-level Gulf Coast League in 1986. After two undistinguished campaigns as primarily a starter, he was converted into a full-time reliever, but missed most of the 1988 season with an assortment of injuries. With just 127⅓ innings under his belt, Radinsky put it all together in 1989 with South Bend in the Class-A Midwest League, earning All-Star honors with a circuit-best 31 saves and sparkling 1.75 ERA in 61⅓ innings while fanning more than four batters for every walk he issued (83 to 19) for the league champions.

Coming off a last-place finish in the AL West in 1989, the White Sox were in desperate need of left-handed relief and looked to Radinsky, as a nonroster player in spring training, for help in 1990. “[He’s] maybe the strangest kid in camp,” suggested sportswriter Alan Solomon in the Chicago Tribune.9 With Bobby Thigpen firmly established as the closer, Radinsky unexpectedly made the squad, joining holdover Ken Patterson as the relief corps’ sole southpaws. “Rad,” as his teammates began calling him, was unintimidated by his surroundings, and quickly became a fan favorite. He cranked up his punk-rock music in the clubhouse and possessed an unflappable and unconventional demeanor not normally associated with baseball players, like riding his bike from his apartment in downtown Chicago to and from Comiskey Park. After retiring the only batter he faced in his debut in the season opener against the Milwaukee Brewers on April 9, Radinsky got off to what Bill Jauss of the Tribune called a “sensational” start, yielding just one earned run and seven hits in his first 17 appearances, covering 14⅓ innings.10 “‘Rad’ has an outstanding arm,” gushed manager Torborg. “And he’s got poise. He has that attitude: ‘I don’t care who’s up. I’ll get him out.’”11 Radinsky boasted a stellar 1.87 ERA as late as July 4, but suddenly hit a brick wall, as if his internal amp had been quickly unplugged. Thereafter he posted a demotion-inspiring 10.13 ERA as he struggled with his control and showed the effects of overwork. While the White Sox had a 25-game turnaround to win 94 contests and finish in second place, Radinsky demonstrated the kind of self-awareness and introspection that came to characterize his approach to pitching. “When I came out of high school,” said Radinsky, “I thought I knew everything about pitching. Well, I’m learning. … I’ve learned you can’t throw without a thinking plan, without pitching sequence.”12

Radinsky was a willing and enthusiastic student. In his rookie campaign, he proved his mettle as a workhorse (62 appearances), but needed to avoid the big inning (4.82 ERA in 52⅓ innings) to ensure his future in the big leagues. In 1991 Rad emerged as one of the best set-up men in the AL and one of the most coveted relievers in majors. While Thigpen failed to reproduce his otherworldly numbers from the previous season (a major-league record 57 saves and 1.83 ERA), Radinsky proved to be the staff’s most consistent reliever, pacing the club with a 2.02 ERA, and tying Thigpen with a team-high 67 appearances for the second-place White Sox. Occasionally thrust into the role of closer, Radinsky saved eight games, but also blew seven chances.

“Radinsky is a barbed original, a punk-loving, jock-loathing lefty,” opined sportswriter Franz Lidz.13 Like the adrenaline rush he got by listening to a two-minute, guitar-infused song by Black Flag, Radinsky seemed ideally suited to the high-pressure, intense lifestyle of a reliever, where everything is calm until that sudden burst of energy on the mound. “I love the five minutes I’m actually in the game,” he told Lidz. “Those five minutes are why I come to the ballpark and put up with the writers, the dress code, the team meetings, the authority of the dugout, the major corporation that is baseball.”14

No dilettante, Radinsky recognized that being a relief pitcher was more than facing two or three batters in a game 70 times a season or accumulating stats readily digested in the newspapers. It required physical and mental dedication with as much action and even more preparation behind the scenes to which the average fan was impervious. “A lot of people don’t realize if you see 60 or 70 games you have to look at the person who threw in those games,” Radinsky said. “Out of the 70 games I did get in, there were probably 30 other games I was one pitch away from getting in that I didn’t get in and I was just as hot and ready to go.”15

“Rad has already gotten that mental state,” said Thigpen in spring training in 1992 about Radinsky’s potential as a closer. “Rad wants to do it. He’s confident he can.”16 Back in the role as set-up man, Radinsky got off to another scorching start, with a 1.64 ERA over his first 25 starts. When Thigpen struggled and was booed mercilessly by the Comiskey Stadium crowd, Radinsky finally had a chance to test his nerves as a closer. “I said in spring training that there’s a lot of clubs that don’t have one closer, and we’re sitting with two of them,” said pitching coach Jackie Brown.17 From July 22 to August 22, Radinsky picked up a save in 10 of 12 chances and posted a 1.32 ERA in 14 appearances. Despite Radinsky’s success, manager Gene Lamont used a closer by committee over the last five weeks with the emergence of another hard-throwing right-hander, future All-Star Roberto Hernandez. The 24-year-old Radinsky appeared in a team-high 68 games (tied for seventh most in the AL) with an impressive 2.73 ERA and 15 saves (eight blown chances) for the third-place Pale Hose.

Led by a pair of 25-year-old sluggers, MVP Frank Thomas and Robin Ventura, and arguably the best quartet of young starting hurlers in the league (Cy Young Award winner Jack McDowell, Alex Fernandez, Wilson Alvarez, and Jason Bere), the 1993 White Sox cruised to their first AL West crown in 10 seasons. Radinsky appeared in 73 games (second most in the league) while Hernandez served as primary closer (38 saves). Radinsky was also transforming into a LOOGY (left-handed one-out only guy). He averaged only about two outs per appearance, logging 54⅔ innings (4.28 ERA) while hampered by a severely strained groin in June. In the White Sox loss to the Toronto Blue Jays in the ALCS, he appeared in four of the six games, yielding four runs (two earned) while registering just five outs.

Health-conscious, Radinsky maintained an active offseason workout regimen of mountain biking and hiking in Southern California. He also toured with his band. “I guarantee you,” said the pitcher-singer, “there is no aerobic workout that a major league baseball player does that’s better than playing live for 45 minutes.”18

Radinsky faced his biggest challenge in February 1994 when he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, a type of lymphoma. “When I got the news it totally sucked,” said Radinsky of learning that he had cancer. “That’s the worst news you can get.”19 He underwent surgery at Sarasota Memorial Hospital and returned to his home in Simi Valley to recuperate. “It was tough to deal with,” he said about the months of radiation and aggressive chemotherapy. “But it was no problem. I had a schedule to do and did it.”20

His White Sox teammates were understandably floored by the news. “It hasn’t sunk in yet,” said pitcher Jack McDowell. “It’s not something you can prepare for.”21 During spring training White Sox players wore a patch of Radinsky’s number 31 on their jersey.

Far from wallowing in self-pity and facing the prospects that his professional baseball career might be over, Radinsky perceived his ordeal as just another bump on the road and as a chance to spend time with his wife, Darlenys (the sister-in-law of White Sox player Ozzie Guillen), and catch up with friends in LA. “I’m about in the same shape I’d be, having to go to spring training,” said Radinsky in early May. “Other than not being able to pitch competitively to real hitters, really good hitters, I’m staying in shape. I’m riding my bike, throwing every day, pitching in a league on Sundays.”22 He also volunteered as a coach at his former high school. Radinsky surprised his teammates and coaches with his health and appearance during the White Sox’ three-game series against the California Angels in mid-May. After throwing on the side for Lamont, Radinsky harbored hopes that he might return to the team in September, just weeks after his chemotherapy was scheduled to finish. That plan was derailed by the baseball strike, which interrupted the season on August 12 and lasted 232 days.

The White Sox showed their loyalty to Radinsky by signing him to a one-year contract for the 1995 season, thus giving him a shot to stage a feel-good comeback. With his characteristic nonchalance, Radinsky relished the moment, but maintained his unique brand of humor. “Comeback?” he responded when queried about his return to the club, “What did I miss?”23 After an 18-month absence from major-league baseball, Radinsky took the mound for the first time in an exhibition game on April 14 (the season had been delayed the end of the strike on April 2), yielding a run and three hits in an inning. “I just wanted to get through an inning, and have some fun,” said Rad.24 After easing along during spring training, Radinksy yielded a leadoff single to Greg Vaughn in the ninth, then retired the next three batters in the season opener on April 26 against the Brewers. “Feels good to finally have a little adrenaline flowing through my body again,” said the tightly-wound southpaw.25 The effects of Radinsky’s lengthy layoff were noticeable. He was easily fatigued, struggled with his control, and landed on the DL in mid-July with a serious groin pull. With a 7.03 ERA, Radinsky was sent to Class-A South Bend for a rehab stint, but return to the club was far from certain. But after tossing 9⅔ scoreless innings for South Bend, Radinsky was back with the White Sox in mid-August. He regained his mid-90s heater and yielded just three earned runs in his final 17 appearances (11⅔ innings), suggesting his career was far from over.

In December 1995 Radinsky was honored with the sixth annual Tony Conigliaro Award for his inspirational return to baseball. He received the award the following January, at the annual dinner hosted by the Boston chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

Notwithstanding Radinsky’s success at the end of 1995, the White Sox did not re-sign him when he was granted free agency in December 1995. “I was crushed when they let me go,” Radinsky said in Sports Illustrated. “I would have accepted any contract, even a minor-league contract.”26 Few teams expressed interest in a 27-year-old middle reliever who had posted a dismal 5.45 ERA in his return after missing a season due to Hodgkin’s disease. The Los Angeles Dodgers took a chance on the hometown product, and signed Radinsky to a minor-league contract in January 1996. “I’m getting the same movement [I used to],” said Radinsky excitedly about his pitches during spring training. “And I know because of the reaction of the hitters.”27 Radinsky surprised everyone with a sturdy spring and was tapped by skipper Tommy Lasorda, in his last of 22 seasons at the helm of the only organization he ever knew, to open the season with the Dodgers.

Radinsky enjoyed the best stretch of baseball in his big-league career in his three years with the Dodgers (1996-1998), posting a stellar 2.65 ERA in 195 appearances. In his first 24 appearances with the club, he yielded only one earned run (in 21⅔ innings) and punched out 19. “You can’t help but love him,” praised Lasorda. He’s a super guy to have on the team.”28 In the Dodgers’ three-game sweep at the hands of Atlanta Braves in the NLDS, Radinsky pitched twice, recording four outs and issuing a walk.

After a staff-leading 75 appearances in 1997, Radinsky was named the Dodgers’ closer in 1998 with the offseason departure of former All-Star Todd Worrell. Described by LA sportswriter Jason Reid as having “nasty stuff,” Radinsky was successful in his first 10 of 12 save opportunities and posted a stellar 1.35 ERA through May 27.29 Thereafter he hit a rough patch, blowing five saves in six chances and losing the closer’s role. On June 4 the Dodgers acquired Cincinnati’s red-hot closer, Jeff Shaw (1.81 ERA), who eventually led the NL in saves with 42. Radinsky once again paced the staff in appearances (62) and posted a sub-3.00 ERA for the third consecutive season.

Granted free agency after the 1998 season, Radinsky signed a lucrative two-year deal with the St. Louis Cardinals worth a reported $5 million. Rad seemed perfectly suited for Redbirds skipper Tony LaRussa who pioneered the use of the LOOGY in the late ’90s and early 2000s. However, the 31-year-old hurler never found his rhythm, struggled with his control, and his ERA skyrocketed to 6.62 on June 11 after his second consecutive meltdown. Bothered by elbow tenderness the entire season, Radinsky landed on the DL after an appearance on July 26. According to Mike Eisenbath of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, team physicians diagnosed “sizable chips” in Radinsky’s left elbow, which were surgically removed in August, ending the reliever’s season.30 “I don’t know what normally comes out of arms,” Radinsky told Cardinals beat writer Rick Hummel, “but I was pretty much blown away by it.”31

Despite expectations to the contrary, Radinsky began the 2000 season on the DL. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, he suffered from a “strained left forearm.”32 I’m frustrated,” said the reliever bluntly. “It’s almost embarrassing.”33 He made his season debut on June 1, and lasted less than one batter. After throwing just three pitches, he was removed because of elbow pain, and was placed in the DL again.34 LaRussa was roundly criticized by the local media for failing to send Radinsky on a minor-league rehab assignment. The Post-Dispatch reported that doctors subsequently determined that Radinsky required season-ending and potentially career-threatening Tommy John surgery and performed the operation on June 9.35

Radinsky wasn’t ready to retire, even after two elbow operations and Hodgkin’s disease. He signed a minor-league deal with the Cleveland Indians, spent most of the 2001 seasons in Double A and Triple A, and made his final two big-league appearances, with the Tribe, when the rosters expanded in September. Released by the Indians in March 2002, Radinsky appeared in 18 games for the Calgary Cannons, the Florida Marlins’ Triple-A affiliate in the PCL, in his final attempt to return to the majors.

At the age of 34, Radinksy retired in 2002. In parts of 11 seasons in the majors, he appeared in 557 games, carved out a 3.44 ERA in 481⅔ innings, and posted a 42-25 record with 52 saves.

Radinsky returned to Los Angeles and his wife, Darlenys, with whom he had three children, daughters Shylene and Rachael, and son Scott. His hiatus from baseball did not last long. After helping the Cleveland Indians in the Arizona Instructional League in 2004, Radinsky was hired by Cleveland in 2005 as a pitching coach for their affiliate in the Class-A South Atlantic League. He moved through the farm system over the next five seasons, then served as Cleveland’s bullpen coach (2010-11) and pitching coach (2012). “I enjoy player development,” said Radinsky. “I enjoy watching guys get from A-to-B-to-C-to-D, and maybe have the opportunity to get to the big leagues.”36 He related well to his players, who were fully aware of the challenges he had overcome in his playing career. Radinksy had the reputation as a “trust your stuff” coach, who was as much as psychologist as he was mentor.37 After three seasons as pitching coach in the Dodgers organization, Radinsky was named the bullpen coach for the Los Angeles Angels in 2016.

As of 2016, Radinsky resided in Los Angeles. A man of varied interests, he continued to tour with his punk band, Pulley, and devote time to Skatelab, a skateboard park he co-founded in the 1990s.

Last revised: January 5, 2017

This biography appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record. Special thanks to Bill Mortell for his assistance with genealogical research.

Notes

1 Alan Solomon, “Radinsky Waits for Closing Time,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1992: C3.

2 Hillel Kuttler, “Out of a Job, but Not Missing a Beat,” New York Times, August 25, 2012.

3 Franz Lidz, “Punk With a Nasty Delivery. Dodgers Reliever Scott Radinsky Throws Smoke and Sings Music That Burns,” Sports Illustrated, July 28, 1997.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Vince Kowalik, “Only 1 Stop Remains for Simi Valley Southern Section Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1993: 8; Vince Kowalik, “Scyphers Addresses One Final Objective,” Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1993: 10.

8 Devon Teeple, “Interview with Scott Radinsky: MLB Player/Coach, Punk Rock Frontman, Entrepreneur, AXA Entertainment, December 12, 2012. http://examiner.com/article/interview-with-scott-radinsky-mlb-player-coach-punk-rock-frontman-entrepreneu.

9 Alan Solomon, “Sox Pitching Blurred,” Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1990: A6.

10 Bill Jauss, “Bullpen Rose. Ideal Set-up for This Pair,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1990: 8.

11Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Lidz.

14 Ibid.

15 Teeple.

16 The Sporting News, July 6, 1992: 12.

17 Solomon, “Radinsky Waits for Closing Time.”

18 The Sporting News, February 22, 1999: 59.

19 Teeple.

20 Paul Sullivan, “Still Laid Back. Radinsky Back. Sox Pitcher Puts Disease Behind Him,” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1995: 9

21 “White Sox Reliever Radinsky Is Examined for Growth on Neck,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 1994: 5.

22 Jeff Fletcher and Mack Reed, “Simi Coach Is Removed Amid Inquiry,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1994: 1.

23 Sullivan, “Still Laid Back. Radinsky Back. Sox Pitcher Puts Disease Behind Him.”

24 Ibid.

25 Paul Sullivan, “Word War. Sore Spot for Selig, Fehr,” Chicago Tribune, April 27, 1995: 10.

26 Lidz.

27 Jerome Holtzman, “Scott (Players Love Him, Man) Radinsky Popping His Old Heater,” Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1996: 3.

28 Ibid.

29 The Sporting News, February 16, 1998: 23.

30 Mike Eisenbath, “Cardinals Notebook,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 14, 1999: 4OT

32 Rick Hummel, “Rick Ankiel Is Sharp in Pitching for Scoreless Inning,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 30-2000: C2.

33 Ibid.

34 Rick Hummel, “Radinsky Returns to DL After 3-Pitch Comeback,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 4, 2000: D10.

35 Rick Hummel, “ ‘Tommy John’ Surgery Ends Radinsky’s Year; McGwire, Vina, Howard Are Back in Outfield,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 10, 2000: 4OT.

36 Teeple.

37 Kuttler.

Full Name

Scott David Radinsky

Born

March 3, 1968 at Glendale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.