Robin Ventura

Robin Mark Ventura was one of the outstanding third basemen of the last decade of the 1900s. After a stellar college career, Ventura played integral parts in the success of the Chicago White Sox and New York Mets during his career.

Robin Mark Ventura was one of the outstanding third basemen of the last decade of the 1900s. After a stellar college career, Ventura played integral parts in the success of the Chicago White Sox and New York Mets during his career.

Ventura was born on July 14, 1967, in Santa Maria, California, to John and Darlene Ventura. His father was of Italian descent and his mother was Portuguese. Ventura grew up with two older brothers, Randy and Rick, and a younger brother, Ryan.

Ventura learned to play baseball at an early age. He was always trying to keep up with his older brothers, recalled his mother, Darlene. “He had to be out there playing. I just told the boys, ‘Just let him play.’ They’d say, ‘He can’t do this or that.’ Well, he started to get a lot better. He never feared playing over his head,” she said.1

He played Little League and that helped Ventura develop his skills early. “It all started from Little League days. We’d all grown up playing not only baseball but all sports,” said Chris Stevens, one of Ventura’s high school teammates. 2

Ventura started for his high school team beginning with his sophomore year. That squad finished the year with a 24-2 record, which is still the best in his high school’s history. He played with many talented players during his high school years. “There were only 14 of them on the team and I think eight ended up playing Division I baseball and they just took care of each other from Day One,” said Derek Moore, high school coach.3

By his senior year, Ventura had developed into one of the best high school players in California. He was walked 30 times in 20 games during his final year at Righetti High School in Santa Maria. 17 of those walks were intentional and one of them came with the bases loaded. Ventura attended Oklahoma State University after graduating high school. “That was the only scholarship I received,” Ventura said later.4

He quickly made his mark on the program, starting at third base for the Cowboys. He led the nation in runs (107), RBIs (96) and total bases (204) in 69 games during his freshman year in 1986. His .469 average as a freshman remains the highest of any Cowboy in a season.

Ventura finished his college career with a .428 batting average. He also set an NCAA record with a 58-game hitting streak in 1987, a record that still stands for Division I schools. He still holds the Oklahoma State career records for batting average, runs (300) and hits (329) and is second all-time in doubles (71), home runs (68), total bases (608), RBIs (302) and slugging percentage (.792).

Ventura helped the Cowboys to the College World Series twice. His 1987 team reached the finals where they eventually lost the championship game to Stanford University. Ventura collected four hits, including a pair of doubles in the final game, and batted .364 for the series.

A three-time All-American, Ventura capped his career by earning the 1988 Golden Spikes Award, given to the nation’s best amateur player. He led Oklahoma State to a school record 61 wins that season while hitting .391 and hitting 26 home runs and collecting 96 RBIs.

Ventura played for the Hyannis Mets in the Cape Cod League in the summer of 1987. He collected 54 hits and driving in 37 runs, tops in the league during their 40-game season. On January 19, 2002, Ventura was inducted into the Cape League Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 2001.

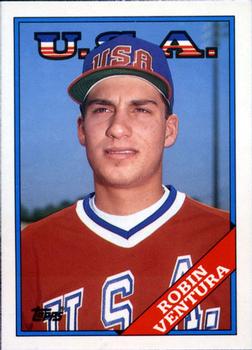

After his junior year at Oklahoma State, Ventura declared for the 1988 MLB Amateur Draft. He was selected as the 10th overall pick by the Chicago White Sox. Before he turned professional, Ventura played for the United States at the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

After his junior year at Oklahoma State, Ventura declared for the 1988 MLB Amateur Draft. He was selected as the 10th overall pick by the Chicago White Sox. Before he turned professional, Ventura played for the United States at the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

Ventura batted .409 during the Olympics tournament and eventually brought home a gold medal as part of Team USA. Ventura said of the Olympics experience: “Winning the gold medal, the whole scene, is something I’ll never forget. I hope I will do something down the road that will make me almost as happy,”5

Chicago sent Ventura to the Class AA Birmingham Barons (Southern League) in 1989. He played 129 games for Birmingham. Ventura batted .278 and hit 25 doubles while collecting 67 RBIs. But he struggled at the hot corner. When the Barons season ended, he had 26 errors. Ventura still managed to earn a spot in the Southern League All-Star Game and was later voted the league’s top third baseman.

Ventura also demonstrated some of the leadership skills that he would show later in his career during his brief stint in Birmingham. Art Clarkson, owner of the Barons, remembers Ventura, saying “He was acknowledged in the clubhouse as a team leader and he was great to work with. When he first got there, he was kind of reserved but as the season went along he opened up.”6

The 1989 White Sox were in need of a third baseman. The previous year, the Sox had experimented with two players who were primarily outfielders at the position, Carlos Martinez and Steve Lyons. Ventura was called up to the majors after the minor league season ended. He played in 16 games for the Sox where he struggled at the plate, hitting just .178 for the month.

Ventura worked hard in the offseason and earned the White Sox starting third baseman position in 1990. Although some may have been surprised by Ventura’s leap from AA ball to the majors, Randy Whistler, who coached him at Oklahoma State was not, saying: “Everything about him was great. You could tell he was a very mature individual. Even during his hitting streak he didn’t let it get to his head. He remained poised.”7

While his 1990 season was marred by 25 errors, Ventura’s 123 hits were the most by a White Sox rookie since Ozzie Guillén in 1985. He also led AL rookies with 150 games played. Ventura batted .249 with 17 doubles, five home runs, and 54 RBIs.

The low point of his rookie season came in May when Ventura went hitless in 41 consecutive at-bats. “A slump like that would have destroyed a lot of young players. [But j]ust looking at him, on and off the field, you knew he was special,” said Whitey Lockman, who had observed Ventura since he scouted him in college.8

“It’s not something to be proud of. But it was also something I learned from. I learned no matter how bad things are, it’ll work out in the end,” Ventura said later of his struggles.9

Ventura became an important part of the White Sox offense in 1991. He raised his batting average 35 points to .284 and hit 23 home runs. Ventura also knocked in 100 RBIs, the first of three times that he would accomplish that during his career. He also improved his fielding percentage 20 points to .959 that season to win his first Gold Glove Award, as he led the American League in putouts that season.

Ventura continued to be an offensive threat in 1992, when he posted a .282 batting average, a .431 slugging percentage and hit 38 doubles. Ventura’s defensive skills won him another Gold Glove. It also earned him a spot on the All-Star team, where he belted a double and an RBI in the American League 13-6 victory.

Ventura saw his batting average drop 20 points to .262 in 1993, although both his slugging and on-base percentages rose slightly. He collected his 500th hit in May and was walked 105 times that season. His 93 RBIs that year was the first time that an American League third baseman had hit 90 or more RBIs in three consecutive seasons since Graig Nettles had done it 15 years earlier (1975–78). Ventura also won his third consecutive Gold Glove.

On August 4, Ventura was involved in an unusual incident with Nolan Ryan. Ryan threw at Ventura in the third inning of the game, hitting him on the elbow. Ryan’s action came one inning after White Sox pitcher Alex Fernandez hit Juan Gonzalez of the Rangers.

Ventura grimaced in pain and began to trot to first base. But after taking a couple of steps, he took a sharp left turn, threw his batting helmet to the ground and charged Ryan. Ryan grabbed Ventura and began to flail away at him, landing punches on his head. Both benches cleared. When the players finally separated, Ventura was ejected along with his manager, Gene Lamont.

“He gave me a couple of noogies on my head and that’s about all,” Ventura said later. Lamont defended Ventura’s actions saying, “He hit Robin and he was the one throwing the punches. He should have been ejected, too. Robin thought he was throwing at him and he did exactly what he should do. It’s strange that that was the only pitch that got away from him all night.”10

As the Sox closed in on the division title that year, Ventura said: “I’m probably enjoying the game more than in any other year. It’s being so close to winning. This is the chance we have to win. You play to win. And if we don’t win I could hit .400 and it wouldn’t matter.”11

The White Sox made the postseason that year, the first time since Ventura had arrived in the majors. He had four hits in the ALCS, including a two-run homer in the ninth inning of fifth game, in the White Sox losing effort against the Toronto Blue Jays, the eventual world champions.

Ventura was having a good season when baseball went on strike in August 1994. He had 15 doubles and 18 home runs when the season came to an end. When play resumed in 1995, Ventura had ten errors in the first 10 games. He also played 18 games at first base that year amid trade rumors that never materialized. He ended the 1995 season with a career-high .295 average.

Ventura hit two grand slams in one game on September 4, 1995. The first one came in the fourth inning off Dennis Cook. He followed that with another blast over the right field fence the following inning off Danny Darwin. Ventura was the eighth player in history to accomplish this feat and the first since Frank Robinson in 1970. “You definitely have to get lucky to do that. To have the bases loaded and do that, it’s kind of a freak thing,” he said after the game.12

Ventura had a successful year at the plate in 1996. His 34 home runs and 105 RBIs were both highs for his career. He won his fourth Gold Glove in 1996 as he also reached a new high in fielding percentage, of .975. When the season finished, Ventura held team records in career homers by a third baseman and grand slams.

In a 1997 spring training game at Ed Smith Stadium in Sarasota, Florida, Ventura slid into home plate and caught his foot in the mud. He suffered a broken and dislocated right ankle and missed much of the season. Doctors originally told him that he would need to sit out the entire season but Ventura returned on July 24. He got into 54 games that season and finished with a solid .799 OPS.

1998 was Ventura’s final season with the White Sox. He won his fifth Gold Glove. Although Ventura only hit .263, his 5.8 WAR was just shy of his career high of 6.0. He also hit 21 home runs and had 91 RBIs.

Even as he continued to have solid offensive numbers, Chicago declined to renew his contract at the end of the season. White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf claimed that his skills were deteriorating. He tried using Ventura’s leg injury as leverage to get him to seek a long-term contract for less money.13

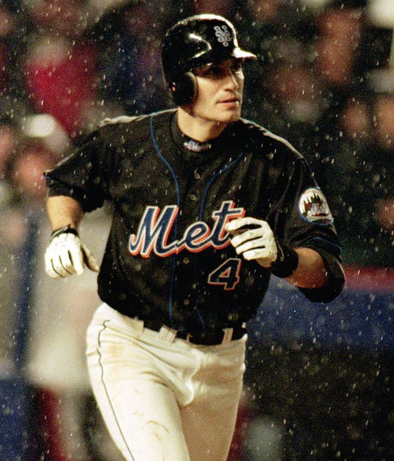

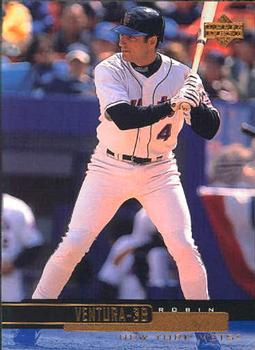

Ventura signed a four-year deal with the New York Mets in December 1998. The Mets planned to use him in their lineup to provide some offensive punch with Mike Piazza and Bobby Bonilla.

He quickly made an impression on his teammates, both on the field and in the clubhouse. “Robin’s very reserved, but he’s also very funny. He’s a great guy to have on your team. But he’s obviously not looking for the spotlight. That’s why he fits in very well with this ball club,” said Mike Piazza. John Franco, the Mets relief pitcher who had been with the team for 10 years, was even more emphatic: “I think Robin Ventura is the best free-agent signing in the history of this franchise.”14

On May 20 Ventura hit grand slams in both games of a doubleheader. The first one came against Jim Abbott in the first inning of the opener when he hit a 3-2 pitch high down the right-field line. The second also came with the bases loaded in the fourth inning of the second game. Once again, Ventura worked the count full before hitting a high fly ball over the right field wall again to help the Mets win the game 10-1. Reliever Horacio Estrada was the victim in the second game.

“You go up and think this can’t happen again. Grand slams don’t happen that often because you don’t get that many situations,” Ventura told reporters after the game. Piazza saluted his teammate’s accomplishment: “It seems like there have been a ton of grand slams this season. But that’s a good week, even a good month by most guys’ standards.”15

The two grand slams in one day gave Ventura a total of 12 for his career. He became the first player to accomplish this feat twice and the only one to hit two grand slams in both games of a doubleheader.

Ventura hit .301 with 32 homers. His 120 RBIs were the highest single-season totals of his career. He had nine errors that year, the second fewest of his career. He previously had seven errors in his injury-shortened season. Ventura also had a .980 fielding percentage and wound up with his sixth Gold Glove award, his first in the National League.

He injured his left knee in August but continued to play. When the problem was finally diagnosed, doctors found that he had torn cartilage. Despite his injury, Ventura hit a game-winning, bases-loaded, two-out single in the 11th inning against the Pirates to keep the Mets in the wild card chase with only three more games left.

The Mets finally made it back to the postseason that year. After defeating Arizona in the NL Division Series, the Mets played the Atlanta Braves, their division rivals for the league championship. In the fifth game, Atlanta was up 3-2 in the 15th inning. After Todd Pratt was given a bases-loaded walk to tie the game, Ventura came to bat.

Ventura hit a home run over the right-center field fence off Kevin McGlinchy, the sixth Braves pitcher. Pratt did not see the ball leave the park and ran back to first base to hoist Ventura into the air and carry him off the field before he could round the bases. The hit was officially scored an RBI single and later became known as a “grand slam single.”16

After having surgery in the off-season to repair injuries to his knee and shoulder, Ventura saw his offensive and defensive statistics drop. He only hit .232 with 24 homers and 84 RBIs in 2000. Ventura spent part of July on the disabled list with inflammation in his repaired shoulder.

After having surgery in the off-season to repair injuries to his knee and shoulder, Ventura saw his offensive and defensive statistics drop. He only hit .232 with 24 homers and 84 RBIs in 2000. Ventura spent part of July on the disabled list with inflammation in his repaired shoulder.

He was plagued with errors throughout the 2000 season but finished strong, hitting .320 with three homers and 13 RBIs in the last two weeks of the season. When the Mets reached the World Series for the first time in 15 years, Ventura hit his only World Series home run against the Yankees’ Orlando Hernández, in the only game the Mets would win, doing so by a 4-2 score.

Ventura continued to struggle at the plate in 2001. He hit .237 with 21 homers and only 61 RBIs. As the season progressed, there was talk that Ventura would be traded. He tried to keep those rumors from interfering with his playing, saying “‘I’m happy to be here, and if they trade me they trade me, and you go somewhere else. You think about it, but now you just play. If they end up trading me somewhere, you deal with it then.”17

The Mets finally traded him to the New York Yankees for David Justice on December 7, 2001. The Yankees believed that the left-handed hitting Ventura would be a good fit in Yankee Stadium, a place that was friendly to left-handed hitters.

Ventura was selected to his second and final All-Star team when he had a hot first half of the season, hitting 19 home runs, 62 RBIs and an .878 OPS. Ventura joined the other three members of the Yankees infield that year on the All-Star team, Derek Jeter, Alfonso Soriano, and Jason Giambi.

Ventura cooled off in the second half of the season to finish with a .247 batting average. He had 27 homers and 93 RBIs in 2002. It was the eighth time that he topped 90 RBIs in a season. When the Yankees reached the postseason, Ventura hit .286 with four RBIs in the ALDS that the Yankees lost to the eventual World Champion Anaheim Angels.

In 2003, Ventura was platooned at third base with Todd Zeile after he struggled through the first few months of the season. By midseason, he had only nine homers and 42 RBIs. At the trade deadline, the Yankees dealt Ventura to the Dodgers for outfielder Bubba Crosby and right-handed pitcher Scott Proctor.

When the trade was announced, Ventura said “I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t disappointed. But I understand the game, and I understand what they were doing. If I have to get traded anywhere, I’m happy it’s to the Dodgers. I grew up in California and that’s a team I rooted for.”18 Ventura hit .220 with five home runs in 49 games as a Dodger.

The Dodgers signed Ventura to a one-year contract at the end of the season. He hoped to become the Dodgers’ starting first baseman in 2004 but ended up on the bench when the team signed Milton Bradley. Ventura saw limited playing time and hit just five home runs. Two of those homers came as a pinch-hitter.

Ventura also hit his 17th career grand slam on August 29 against New York Mets starter Kris Benson. Less than two weeks later, he hit his 18th career grand slam off Chad Durbin on September 7 against the Arizona Diamondbacks. When he finally retired, Ventura was tied for fifth place with Willie McCovey for career grand slams.

He also made his pitching debut on June 25 during a blowout loss against the Anaheim Angels. Dodger manager Jim Tracy called on Ventura to pitch the ninth inning. He allowed a single amid three fly ball outs.

Ventura retired after the season due to arthritis in his right ankle. He finished his 16-year career with 294 home runs, 1,182 RBIs, an .806 OPS and 56.1 WAR. “I’m absolutely positive. I’ve realized that it’s time to go, and that’s it,” he said after the Dodgers were eliminated in the postseason.19

After his retirement, Ventura returned to his home in Arroyo Grande, California where he helped his wife raise his kids. He volunteered as a hitting instructor and groundskeeper for the local high school baseball team. “I’d walk outside, and there’s Robin shoveling dirt. He was out there for eight hours one day making sure it was ready for the game,” said Dwight MacDonald, the athletic director at Arroyo Grande High.20

Ventura also provided color commentary for the College World Series in 2010 and 2011. He worked alongside Mike Patrick and Orel Hershiser both seasons.

He returned to the White Sox in 2011 when they hired him to scout the Sox minor-leagues throughout the season. Ventura evaluated player performances and report directly to Buddy Bell, Chicago’s Director of Player Development. “Robin’s experience and expertise will be invaluable to our entire minor-league system. He will serve as a terrific complement to our instructors and minor-league coaching staffs. I can’t imagine a better role model and advisor for young developing players in our farm system,” Bell said at the time.21

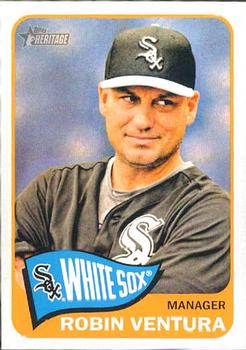

When the White Sox fired their interim manager, Don Cooper, at the end of the 2011 season, they hired Ventura as their manager less than two weeks later. His hiring caught many in baseball by surprise since he had no previous managerial experience. White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf said about Ventura, “There’s no one trait a manager needs to have. Robin reminds me of [Chicago Bulls coach] Phil Jackson — laid-back but smart. I have the same feeling about Robin that I had about Phil.”22

Ventura told the press at the time that “[w]hen I rejoined the White Sox, I said this was my baseball home and that part of me never left the White Sox organization. Managing a major league baseball team is a tremendous honor. It’s also an opportunity and a challenge.”23

Ventura told the press at the time that “[w]hen I rejoined the White Sox, I said this was my baseball home and that part of me never left the White Sox organization. Managing a major league baseball team is a tremendous honor. It’s also an opportunity and a challenge.”23

Ventura led the White Sox to an 85-77 record in his first year at the helm. Chicago finished three games behind the Tigers in their division. He accepted a one-year extension on his contract before the 2013 season. Although the White Sox finished with a 63-99 that season, the White Sox management had enough confidence in Ventura to sign him to a three-year extension.

White Sox general manager Rick Hahn explained the team’s reasoning: “His communication, his ability to teach at the big league level, his enthusiasm, his baseball intellect. All the things we [are] looking for in a manager were the same at our highest highs and our lowest lows. And that level of stability is what we want from a leader in the dugout.”24

In 2008, when the Yankees held their final Old-Timer’s Day at the old stadium, the White Sox were the visiting team. As the Yankees honored as many former players as possible, they took time to recognize Ventura. Yankee announcers Michael Kay and John Sterling introduced the White Sox manager, who emerged from his dugout to tip his cap and take in the fans’ applause.

The White Sox continued to struggle over the next three seasons under Ventura’s management. The team never won more than 78 games and finished fourth in the AL Central every year. At the end of the 2016 season, he met with the team’s management and told them that he wasn’t going to return.

“I was pretty frank about it,” Ventura said later. “I just went to Rick [Hahn, White Sox general manager] and had a conversation of what was going on and what I felt was best. You’ve been in a place a long time and you care about it a lot, but it just got to a point where that was what I felt should happen.”25

The Mets expressed interest in Ventura as their manager prior to the 2018 season. He said that he was not interested and did not accept an invitation to interview for their manager opening. “I’m not pursuing any [managerial] openings,” Ventura said at the time.26

Ventura married Stephanie Hebard in 1990. They have four children: Jack Robert Ventura, Rachel Dane Ventura, Madison Elizabeth Ventura, and Grace Alaina Ventura. After he resigned as the White Sox manager, he returned home to California, where he lives today.

Ventura is remembered as one of the key players on the White Sox and Mets in the 1990s and early 2000s. His connection to the White Sox also led to his only managerial job. It was one that he achieved with no other experience, which is a rare accomplishment in baseball.

Last revised: December 26, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com for player, team, and season pages, and other pertinent material.

Notes

1 Elliott Almond, “In Chicago, They’re Counting on No. 1 Choice Ventura to Pull Up White Sox,” Los Angeles Times, November 3, 1989.

2 Brad Memberto, “Winning Warriors Reunite,” Santa Maria Times, November 18, 2013.

3 Ibid.

4 Jason Diamos, “For Mets, Ventura Makes A Lasting First Impression,” New York Times, August 8, 1999.

5 Almond.

6 Solomon Crenshaw, “Former Baron Robin Ventura returns to Birmingham as manager of Chicago White Sox,” AL.com, March 26, 2014.

7 Almond.

8 Jerome Holtzman, “Winning Comes First With Ventura,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1993.

9 Ibid.

10 Joey Reaves, “Aug. 4, 1993: The Robin Ventura vs. Nolan Ryan fight,” Chicago Tribune, August 4, 2017.

11 Ibid.

12 Paul Sullivan, “Ventura’s 2 Grand Slams Too Grand For Rangers,” Chicago Tribune, September 5, 1995.

13 Phil Rogers, “On Ventura Highway, Sox Signs All Read Exit, Chicago Tribune, January 18, 1998.

14 Diamos.

15 Ben Walker, “Ventura Becomes First to Hit 2 Grand Slams in a Twin Bill,” Deseret News, May 21, 1999.

16 Patrick Bringley, “This Date in Mets History: October 17-Grand Slam Single,” Amazin Avenue.com, October 17, 2012.

17 Buster Olney, “Ventura Could Be Headed to the Yankees,” New York Times, August 16, 2001.

18 Tyler Kepner, “Yankees Make Big Decisions With Deadline Trades,” New York Times, August 1, 2003.

19 “Ventura Says He Is Retiring,” New York Times, October 12, 2004.

20 Albert Chen, “Robin Ventura’s Rockin’ a Manager’s Cap, Sports Illustrated, March 19, 2012.

21 Paul Banks, “Robin Ventura Returns to White Sox as Minor League Advisor,” ChicagoNow.com, June 6, 2011.

22 Chen.

23 Ariel Sandler, “The Chicago White Sox Have Named Former Player Robin Ventura Their Next Manager In A Surprising Move,” Business Insider, October 7, 2011.

24 Scott Merkin, “White Sox, Ventura agree on multiyear extension,” MLB.com, January 24, 2014.

25 Scot Gregor, “Ventura ‘at peace’ after turbulent run as Chicago White Sox manager,” Chicago Daily Herald, February 26, 2017.

26 Mike Puma, “Robin Ventura doesn’t want to manage Mets — or anywhere,” New York Post, October 17, 2017.

Full Name

Robin Mark Ventura

Born

July 14, 1967 at Santa Maria, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.