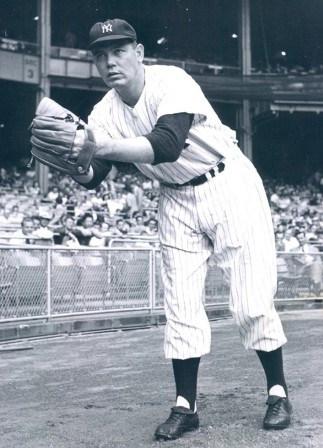

Tom Ferrick

Tom Ferrick was a baseball lifer. The right-hander won Game Three of the 1950 World Series, pitching in relief for the Yankees, a high point of a playing career in the majors that spanned 12 years. He served three years in the Navy in World War II and pitched for five teams from 1941 to 1952. Ferrick spent nearly 60 years as a player, coach, and scout.

Tom Ferrick was a baseball lifer. The right-hander won Game Three of the 1950 World Series, pitching in relief for the Yankees, a high point of a playing career in the majors that spanned 12 years. He served three years in the Navy in World War II and pitched for five teams from 1941 to 1952. Ferrick spent nearly 60 years as a player, coach, and scout.

Beginning in 1954, Ferrick was the pitching coach for four different teams into the 1965 season. As a scout for more than two decades for the Kansas City Royals, he recommended that the team draft George Brett.

Ferrick served as the Washington Senators’ player representative to the Major League Players Association during the period when the pension plan was instituted. Later, he fought for increased pension payouts and to include those who had played in earlier years.1

Thomas Jerome Feerick — he changed the spelling by the time he signed a contract2 — was born in New York City3 on January 6, 1915, to Tom Feerick and his teenage wife, whose maiden name was Maher.4 Tom was one of two brothers. His father, an infielder who played for the semipro Keebler Baking Company team,5 got his son interested in the game but died when Tom was 9 years old. Ferrick was raised in an extended Irish Catholic family headed by his grandfather, a doorman at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.6

After attending Holy Family parochial school in the Bronx, young Tom was sent to the Glenclyffe Seminary in Garrison, New York, for his high-school years to begin training for the priesthood. Ferrick, who eventually grew to over 6-feet-2, had begun by then to show promise as a pitcher. While he was still at the seminary, the Yankees expressed interest in him, but his family would not let him sign a contract.

His mother had remarried, but when his stepfather, Leo, died, Tom had to work to help support her and his younger brother. He drove a truck, but kept playing sandlot baseball when he could. Through a family connection with a team trainer named Willie Schaeffer, Ferrick became a batting-practice pitcher for the New York Giants.7

Before his batting-practice job with the Giants, Ferrick had a chance to pitch in a similar capacity to Babe Ruth in Yankee Stadium. In what would have been 1933 or 1934, Ferrick already was playing for a semipro team while he was still a seminary student. Ruth had fallen ill and was recovering while the Yankees were away. Several school-age pitchers, including Ferrick, were recruited to throw batting practice to The Babe and to shag fly balls. In a 1992 interview, Ferrick called it one of his two biggest baseball thrills, the other being his World Series win.8

Another odd job Ferrick held during the Depression was playing for a basketball team that was paid to perform on stage as the entertainment between two films at movie theaters, his son Tom said. Years later, when he was a coach, Ferrick worked during the Christmas-shopping season at Gimbel’s department store in Philadelphia.9

After a year of throwing batting practice at the Polo Grounds, Ferrick was approached by Giants manager Bill Terry. “Youngster, you can pitch for me at Greenwood next year if you want,” Terry told Ferrick in September 1935. “We’ll see what you can do.”10 That January, once Ferrick turned 21, he signed a Giants contract. At Greenwood, Mississippi, in the Class C Cotton States League, he threw 220 innings with a league-best earned run average of 2.17 and a 13-8 won-lost record. He won the pennant-clinching game for Greenwood, 1-0. An April 1937 newspaper story identified Ferrick by the nickname Swede, even though he was thoroughly Irish.11

The next season, Ferrick went 20-12 and pitched 279 innings for Richmond, Virginia, in the Class B Piedmont League. As a reward for being named the team’s best player, a cigar box was passed around in the stands for fans to toss in coins. As this was during the Depression, the proceeds were just enough for him to get a bus ticket home to New York.12

When the minor-league seasons ended in early September in 1936 and ’37, Ferrick returned to New York. The Giants had him pitch batting practice before games of the World Series in both years.13

After his excellent season in Richmond, Ferrick pitched in just eight games with Jersey City in the International League in 1938 before injuring his arm. He felt stiffness after a game. The next time on the mound, “I tore a muscle loose from the bone in my shoulder. I could feel it go,” he told columnist Red Smith in 1950. “I tried pitching (to get) the soreness out but that kept making it worse.”14

Although Ferrick was with the Giants in spring training for a third time in 1939, his arm had not recovered. Still, the Giants refused to release him, despite showing no further interest in his career. According to his son Tom, Ferrick was forced to write to Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis, who granted his release. The letter from the commissioner was among an extensive collection of baseball documents and his father’s old scouting reports that Tom Ferrick Jr. donated to the Hall of Fame and Museum. “My father was a bit of a pack rat,” he said.15

Ferrick didn’t pitch in 1939, but got a job as a pipefitter in the Jersey City (New Jersey) Navy shipyard,16 where he met Ernie Smith, who had played briefly for the White Sox. Smith sent Ferrick to see Doc Gallagher, the trainer for St. John’s University. “Gallagher worked on my arm … and finally got it back into shape … strong as it ever was,” Ferrick told Harold Rosenthal for The Sporting News in November 1953.17

In 1940 Ferrick signed on with the semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks, where he played first base when he wasn’t pitching. “He was a good hitter,” son Tom said. While he was there, a bird-dog scout brought Ferrick to the attention of Athletics manager Connie Mack.18

Despite his size — his playing weight was about 225 pounds — Ferrick was not a hard thrower after his arm injury, relying instead on curves, sliders, and sinkers. He had good control and hit just one batter during his career. For his career, he averaged three walks per nine innings. More than a few of them were intentional.19

Ferrick debuted with the Athletics in relief against Boston on April 19, 1941, and pitched three scoreless innings. On May 28 against the Red Sox, he pitched the last 10 innings of a 16-inning game, yielding one run before Philadelphia scored twice in the 16th to win. Ferrick finally started a game on August 14, going eight innings. On August 21, in his second start, Ferrick shut out the Red Sox on a four-hitter. That shutout, the only one of his career, lowered his earned-run average to 2.27.

Ferrick’s last five appearances in ’41, two of them starts, didn’t go as well: He yield 25 runs in 20⅓ innings. Overall, he was 8-10 in 36 games with a 3.77 ERA for a Philadelphia team that finished in last place. Before the season ended, he was sent on waivers to the Cleveland Indians, but didn’t appear in a game.

During the 1939 season, Ferrick roomed with a young man working for a Philadelphia newspaper. The roommate went on to become a famous sports columnist who would one day write about Ferrick as a Yankee: Red Smith.20 Shortly after Ferrick arrived in Philly, he met the woman who would become his wife — Dolores Marie Sprows, still in her teens — at a lunch counter in South Philadelphia. They were introduced by shortstop Al Brancato, a Ferrick teammate.21

Before he died in 1996, Ferrick was among a dwindling number of players who had been managed by Mack. He served as a pallbearer at Mack’s funeral in 1956.22 In a 1987 column by Jerome Holtzman, Ferrick remembered Mack with affection.

“He didn’t talk to me much, but he knew who you were. After I left the A’s — it was an office mix-up; they forgot to withdraw my name from the waiver list — I was living with my mother and having a tough time,” Ferrick told Holtzman. “I wasn’t sure I’d get through the winter. Connie heard about it, called me in and gave me a check for $1,000. … A thousand dollars in those days is like $50,000 right now.”23

Pitching out of the bullpen in 29 of his 31 games for Cleveland in 1942, Ferrick posted a 1.99 ERA. He seemed on verge of success in the majors, but a world war was raging.

On December 25, 1942, Ferrick enlisted in the US Navy. He was assigned initially to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. There, he pitched for a team, managed by Mickey Cochrane, that defeated several major-league squads in exhibitions.24 While serving in Hawaii in 1944, he played on a service baseball team and starred in the 1944 Pacific Service World Series between the Navy and the US Army. In 1945 Ferrick pitched for the Fifth Fleet team during the Navy’s Western Pacific Tour. By then he had risen in rank to chief petty officer. He was discharged in January 1946.25

Ferrick married Dolores Sprows on November 17, 1945.26 Before she wed, Mrs. Ferrick had worked at RCA in Camden, New Jersey, and in the finance department at the Warwick Hotel in Philadelphia.27

The couple had four daughters — Kate, their first-born, Jean, Mary, and Ellen — and two sons — Thomas and Patrick — born between 1947 and 1958. Thomas Ferrick Jr., born in 1949, became a reporter and columnist with the Philadelphia Inquirer and shared a Pulitzer Prize in 1980 for the newspaper’s coverage of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. He left the paper after 31 years, but as of 2018, he continued to work on free-lance projects and write commentaries on political issues.28

After leaving the Navy, Ferrick returned to the Indians, pitching in nine games before being sold the St. Louis Browns on June 24, 1946. He was 4-1 with a 2.78 ERA for a seventh-place team that lost 88 games. Retrospectively, he would have been credited with five saves and his WHIP (walks and hits per innings pitched) was an impressive 0.959. Nonetheless, he was sold to the Washington Senators on January 15, 1947. He was used sparingly but made it count. Ferrick saved 9 games in just 31 appearances in 1947 and 10 more in 37 games in ’48 for the Senators.

On August 4, 1946, Ferrick won both games of a doubleheader in relief for the Browns over the Athletics. The next season, on August 20, he lost both games of a twin bill for Washington against Cleveland.

After the ’48 season ended, Ferrick was traded back to the Browns, along with another player, for infielder Sam Dente. Ferrick played in a career-high 51 games for St. Louis in 1949, including one game in which he made his only pinch-hitting appearance. His lifetime average was .184 in 163 times to the plate. He never homered, but he struck out just 32 times and was described in The Sporting News in 1955 as “the fungo king.”29

The Browns and Senators traded places through the late 1940s at the bottom of the American League, but somehow Ferrick managed to avoid being on the team that finished last — small consolation when the 1949 Browns finished seventh with 101 losses. Yet Ferrick was 6-4 with a 3.88 ERA and six saves. He suggested later that the workload hurt his effectiveness.30 So it’s easy to imagine how happy he was when he ended up with the Yankees for a brief time.

“It may not sound good to say it, but when … the club’s not going anywhere, you just try to have a good year for yourself in hopes of getting a raise,” Ferrick told Red Smith in August 1950. “When you win a game or save one here (in New York), you feel as if you’ve done something.”31

On June 8, 1950, just before he was traded to New York by the Browns, Ferrick entered a game in which St. Louis was being crushed by the Red Sox, 29-3. After the Sox had scored five times on three homers in the eighth, Ferrick got the last two outs and kept the Browns from being the first team in the twentieth century to give up 30 runs in a game.

On June 15, 1950, Ferrick was traded to the Yankees as part of a seven-player deal. With New York, he went 8-4 with a 3.65 ERA and 9 saves in 11 opportunities, helping the Yankees win the pennant.32 Yankees general manager George Weiss was criticized when he obtained Ferrick rather than a bigger name pitcher, but by September Ferrick had changed the minds of most. “Where would the Yankees be right now if it weren’t for the gilt-edged relief pitching of that same Ferrick?” New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley wrote in September.33

The Yankees were in St. Louis when Ferrick was traded. He just switched clubhouses in the afternoon and came in for New York that night in relief of Vic Raschi, who became his road roommate. He pitched two innings for a save. On July 17 he saved Whitey Ford’s first major-league win, 4-3 over Chicago.

In the 1950 World Series, which was far tighter than the four-game sweep by the Yankees would indicate,34 Ferrick was the winner in Game Three in relief of Ed Lopat when Jerry Coleman hit a run-scoring single in the bottom of the ninth. It was his biggest thrill in the majors. “It has to be,” he told a reporter. “I was with only two first-division teams … the ’42 Indians and the ’50 Yankees.”35 Yankees teammates voted Ferrick a full share of the World Series money.36

The extra $6,446 paycheck37 came in handy, Ferrick’s son Tom said. According to Michael Haupert’s research on player salaries, Ferrick’s 1950 contract paid him just $8,500.38 Ferrick used the Series money to put a down payment on the family home in the Philadelphia suburb of Havertown and to buy a wood-paneled station wagon and a dining room set, both of which served the Ferricks for many years.39

Ferrick remained with the Yankees for exactly one year. On June 15, 1951, he was traded with pitchers Bob Porterfield and Fred Sanford to the Senators for left-hander Bob Kuzava. Although Ferrick pitched well for the Senators, Porterfield was a revelation, winning 22 games for Washington in 1953.

On September 28, 1952, at Fenway Park, Ferrick pitched four scoreless innings and was the winner in a 5-4 Senators victory. The season-ending win let Washington finish at 78-76, the last time the original Senators had a winning year. It also was Ferrick’s last time on a major-league mound.

At the end of the 1952 season, the 37-year-old Ferrick was released by Washington. Despite that, Ferrick had a soft spot for Clark Griffith, owner of the Senators. When Griffith let him go, “He told me how sorry he was. He had to make room for some young pitchers. He was right. … He thanked me for all I had done for the club,” Ferrick told Holtzman. “He didn’t have to do that. Most of the time they give you the pink slip; they don’t say goodbye.”40

Assessing his own career in 1957, Ferrick was self-deprecating. “I never had too much stuff. A medium-rare fastball and a fairish curve. That’s all. I toyed with the knuckler but rarely threw it. But I could get the ball over the plate and that’s the main thing with a relief pitcher. … I wasn’t much. I’d keep the curveball low and outside and hope the batter would bite.”41

Ferrick wasn’t out of work long. He took a job as a player-coach with Indianapolis, Cleveland’s top farm club. He appeared in 23 games in 1953, his last as a player. The team was managed by Birdie Tebbetts, whom Ferrick had met during a barnstorming tour after the 1950 season.42 Tebbetts took Ferrick along with him to Cincinnati when he was hired as manager there. While at Indianapolis, Ferrick persuaded Tebbetts to turn Ray Narleski into a relief pitcher. By the next season, Narleski had developed into one of the top relievers in the AL. With Cincinnati in 1954, Ferrick helped Joe Nuxhall become a consistent winner by teaching him to throw a slider.43

“Credit for the development of some of our hurlers belongs to Tom Ferrick,” Tebbetts said in August 1956.44 “I never met a fellow so serious about baseball in my life.”45

Others also took note. “Ferrick’s huge contribution to the rise of the Rhinelanders has been the most under-publicized good baseball job in memory,” Harry Grayson wrote in a syndicated column in March 1957. “Each season,” Ferrick pointed out about his partnership with Tebbetts, “we have brought down our pitchers bases-on-balls, earned-run averages, and home-runs-given-up.” 46

By then, Ferrick had been selling insurance in the offseason for several years, which frequently became the source of good sports copy. A quip identified with him during his years in Cincinnati, often recited in various forms, was typical of his wit: “I quit pitching when the insurance rates went up. I was no longer a good risk against those line drives.”47 He once told an aging and ineffective Bobo Newsom, “I canceled your insurance. I don’t insure combat cases.”48

Ferrick remained the Reds’ pitching coach from 1954 through 1958, then moved to the same job with Philadelphia in 1959. He was the Tigers’ pitching coach from 1960 until June 1963, when manager Bob Scheffing and the entire coaching staff were fired. Ferrick was the pitching coach for the Kansas City Athletics in 1964 and until midseason 1965, his last season in uniform. The Athletics made him the team’s chief scout in 1966.

“I never want to manage.” Ferrick said in 1961. “I have a minor ulcer. It’s the badge of the game. Managing might make it worse.”49

Initially, Ferrick was uncertain whether he was cut out for scouting. He assumed he would be out of a job after the managerial change in Kansas City before Hank Peters, then the farm director of the A’s, summoned Ferrick to his office.

“Why don’t you scout for us?” Peters suggested. “I had to make a living,” Ferrick told Holtzman. “I had six children. … Some of the kids were getting ready to go to college.” Ferrick went to Vancouver to study the A’s top farm club. After a week, he sent in a report on each player. Peters called it “one of the best reports we’ve ever had.”50

Ferrick joined the expansion Kansas City Royals in November 1968 and remained a special-assignment scout with the team for more than two decades before retiring after the 1987 season. He remained a part-time consultant for the Royals until 1994.

“He was one of the top people they brought in to formulate the club,” said Art Stewart, who was director of scouting for the Royals when Ferrick died. “He was instrumental in evaluating and getting into place those many great players who helped us win early pennants.”51 Although he wasn’t the Royals scout who first touted Brett, Ferrick persuaded the front office to select the future Hall of Famer in the second round of the 1971 draft.52

The Royals’ new manager, Jim Frey, tried to get Ferrick back into uniform late in 1979, offering to make him the team’s pitching coach, but Ferrick said he’d rather remain a scout.53 By then, about to turn 65, he was concentrating on National League East teams, looking for players the Royals might want to acquire. Ferrick did join Frey’s field staff briefly early in spring training of 1980 to work with the pitchers.54

In April 1996 Ferrick suffered a stroke and heart attack. He spent his last months at a life-care center before he died of heart failure at age 81 at Riddle Memorial Hospital outside Philadelphia on October 15, 1996.55 He and his wife, who died in 2006, are buried together at Saints Peter and Paul Cemetery in Lima, Pennsylvania, in Delaware County.

“I wish I had taken a tape recorder,” Tom Ferrick Jr. said of his visits with his father after the senior Ferrick had fallen ill. Although his father never before had talked much about his baseball career, he began to tell his son story after story in the months before he died.56

“He had a terrific knowledge of the game and the players,” Mickey Vernon, the two-time American League batting champion, Senators teammate, and longtime friend, said of Ferrick.57

Ferrick’s philosophy for pitching was simple: “Get the ball over the plate with something on it,” he told Red Smith in 1950, “And keep it low.”58

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the help of Tom Ferrick Jr. with this biography. It was edited by Len Levin and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

Career statistics: https://baseball-reference.com/players/f/ferrito01.shtml.

Game summaries: https://retrosheet.org/boxesetc/F/Pferrt101.htm.

Notes

1 Andy Wallace, “Ex-Pitcher Tom Ferrick Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 17, 1996: E1.

2 Telephone conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr., October 31, 2018. (All subsequent endnotes citing a conversation with Ferrick Jr. are from that date.)

3 Findagrave.com says Ferrick was born in Manhattan. The SABR/Baseball-Reference Encyclopedia says he was born in the South Bronx. The Sporting News in 1953 wrote that he was born in the Port Morris section, also in the South Bronx. Sportswriter Arthur Richman wrote in 1950 that Ferrick was “a product of the East Bronx.”

4 Neither Tom Ferrick Jr. nor his older sister, Kate DeLosso, knew the first name of their father’s mother, who died during World War II. I was unable to determine her first name from census records.

5 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

6 BaseballReference.com Bullpen page for Ferrick, https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Tom_Ferrick.

7 Harold Parrott, “Studying for Priest Made Rookie Patient,” newspaper clipping from Ferrick’s Hall of Fame player file; source is unidentified, although probably from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

8 Rich Marazzi, “Tom Ferrick Remembers ‘The Babe’ and More,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 10, 1992: 230.

9 Ibid.

10 Parrott.

11 Ibid.

12 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr. and an account on his father’s BR Bullpen page.

13 Marazzi.

14 Red Smith, “Man at Rest,” New York Herald Tribune, August 29, 1950: 25.

15 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

16 Marazzi.

17 Harold Rosenthal, “Ferrick Answers Third Call from Tebbetts,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1953: 5.

18 Ibid.

19 Wallace.

20 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

21 Marazzi.

22 Ibid.

23 Jerome Holtzman, “Put Yourself in a Scout’s Seat,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1987: 3.

24 “Sailors Sink Cleveland,” In the Service column, The Sporting News, June 24, 1943: 6.

25 Ibid.

26 J.G. Taylor Spink, Paul Rickart, and Joe Abramovich, eds., Baseball Register — 1957 Edition (St. Louis: Sporting News Publishing Co.), 272.

27 “Dolores S. Ferrick, Baseball Wife, 83,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 9, 2006; clipping from Ferrick’s player file at the Hall of Fame and Museum.

28 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

29 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book” column, The Sporting News, April 13, 1955: 15.

30 Smith.

31 Ibid.

32 “Saves” did not become an official statistic until 1969, although some sportswriters had begun noting them (under varying standards) as early as 1952. In most cases here, the saves are a retrospective statistic.

33 Arthur Daley, “Insurance Man,” New York Times, September 6, 1950: 51.

34 The Yankees won Game One of the 1950 World Series 1-0, won Game Two 2-1 in 10 innings and Game Three 3-2 before completing the sweep with a 5-2 win.

35 Wallace.

36 Rosenthal.

37 Tom Swope, “It Also Pays To Be a Yankee; 52 Divide World Series Pot,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951: 10.

38 baseball-reference.com/players/f/ferrito01.shtml.

39 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

40 Holtzman.

41 “Ferrick Says Good Reliever Is Equal to a 20-Game Winner,” Salisbury (Maryland) Times, February 27, 1957: 13.

42 Rosenthal.

43 Arthur Daley, “Height of Precocity,” New York Times, March 28, 1956: 39.

44 Tom Swope, “Birdie Adds ‘Big 4’ to ‘Big 4’ and Gets Pennant as Answer,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1956: 10.

45 Frank Eck, Associated Press, “Tom Ferrick Big Help to Redleg Pilot,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, September 29, 1956: 5.

46 Harry Grayson, Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Figures Tell Story of Ferrick’s Job on Reds’ Pitching,” Rhinelander (Wisconsin) Daily News, March 18, 1957: 8.

47 “Sports Flashes,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), May 21, 1956: 7.

48 Bob Addie, “Spring Brings High Hope, Minor Tragedies,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1975: 18.

49 Eck, “Spahn Has Mental Image of Each Batter — Ferrick,” Oil City (Pennsylvania) Derrick, July 6, 1961: 12.

50 Holtzman.

51 Wallace.

52 BR Bullpen, https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Tom_Ferrick.

53 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1979: 12.

54 “Royals Notes,” January 5, 1980, newspaper clipping from Ferrick’s Hall of Fame file from unidentified source.

55 Wallace.

56 Conversation with Tom Ferrick Jr.

57 Ibid.

58 Smith, “Professor of Pitching,” New York Herald Tribune, February 21, 1951: 22.

Full Name

Thomas Jerome Ferrick

Born

January 6, 1915 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

October 15, 1996 at Lima, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.