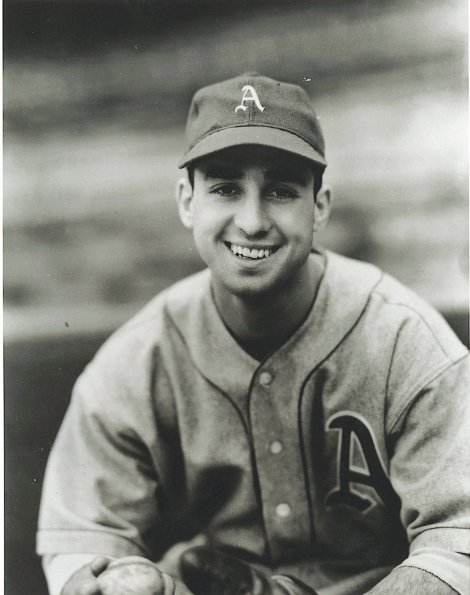

Al Brancato

The fractured skull Philadelphia Athletics shortstop Skeeter Newsome suffered on April 9, 1938 left a gaping hole in the club’s defense. Ten players, including Newsome after he recovered, attempted to fill the void through the 1939 season. One was Al Brancato, a 20-year-old September call-up from Class-A ball who had never played shortstop professionally. Enticed by the youngster’s cannon right arm, Athletics manager Connie Mack moved him from third base to short in 1940. On June 21, after watching Brancato retire Chicago White Sox great Luke Appling on a hard-hit grounder, Mack exclaimed, “There’s no telling how good that boy is going to be.”1

The fractured skull Philadelphia Athletics shortstop Skeeter Newsome suffered on April 9, 1938 left a gaping hole in the club’s defense. Ten players, including Newsome after he recovered, attempted to fill the void through the 1939 season. One was Al Brancato, a 20-year-old September call-up from Class-A ball who had never played shortstop professionally. Enticed by the youngster’s cannon right arm, Athletics manager Connie Mack moved him from third base to short in 1940. On June 21, after watching Brancato retire Chicago White Sox great Luke Appling on a hard-hit grounder, Mack exclaimed, “There’s no telling how good that boy is going to be.”1

Though no one in the organization expected the diminutive (5-feet-nine and 188 pounds) Philadelphia native’s offense to cause fans to forget former Athletics infield greats Home Run Baker or Eddie Collins, the club was satisfied that Brancato could fill in defensively. “You keep on fielding the way you are and I’ll do the worrying about your hitting,” Mack told Brancato in May 1941.2 Ironically, the youngster’s defensive skills would fail him before the season ended. In September, as the club spiraled to its eighth straight losing season, “baseball’s grand old gentleman” lashed out. “The infielders—[Benny] McCoy, Brancato and [Pete] Suder—are terrible,” Mack grumbled. “They have hit bottom. Suder is so slow it is painful to watch him; Brancato is erratic and McCoy is—oh, he’s just McCoy, that’s all.” 3 After the season ended Brancato enlisted in the US Navy following the country’s entry into the Second World War. When he returned to the Athletics in August 1945, Brancato appeared in just 10 games. Assigned to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs in November, he bounced around Organized Baseball over the next eight years without ever retuning to the big leagues.

Albert “Bronk” Brancato (he did not have a middle name) was born on May 29, 1919, the youngest of seven children of Italian immigrants Giuseppe “Joseph” and Maria Luigia (Tesauro) Brancato, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.4 His parents arrived in the United States separately in the 1890s and married in Philadelphia in 1900. In the 1910 US census Joseph was listed as a vegetable peddler. He and his wife would eventually own and operate two produce stores in South Philadelphia. The couple’s ambitious drive extended to their children. In 1932, their eldest daughter Anne “made history by becoming the first female Democrat to be elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature.”5 Moreover, their third son Joseph, a standout gymnast at Temple University, went on to earn his doctorate at Penn State University.6

The Brancato’s youngest child had the ambitious streak too. Al attended South Philadelphia High School in the working-class neighborhood west of the naval shipyard. Renowned for an illustrious list of alum in sports and entertainment, South High also launched Brancato’s superb athleticism. He lettered in four sports (baseball, football, basketball and gymnastics) while making a name for himself on the semi-pro circuit as well. “I play[ed] . . . with all of the local players who would come back from playing pro ball who couldn’t make any money there,” Brancato recalled years later. “That’s how I honed my skills, playing with the older guys and playing against the black teams in Chester [a small city on the southwesterly outskirts of Philadelphia]. You learned from being around those guys. The talk, how they played, you watched all of this. The leagues around Philadelphia were very good.” 7 It was on these same sandlot diamonds that scout Phil Haggerty, who had worked for the Athletics since 1924, first spied Brancato. Credited with signing catcher Bill Conroy and pitcher Porter Vaughan among others, in 1938 the longtime sandlot player and manager was instrumental in Connie Mack’s signing Brancato to a $1,000 bonus weeks before the youngster had received his high school diploma. 8

Brancato spent most his first professional season with the Class-B Greenville (SC) Spinners in the South Atlantic League (he also played 11 games with the Athletics’ highest minor league affiliate, the Class-A Williamsport [PA] Grays in the Eastern League). He shared third base duties with veteran Frank Skaff and roomed with future major league All Star first baseman Mickey Vernon, and the trio placed among the team leaders in nearly every offensive category. Brancato and Vernon also ranked among the league leaders in triples—15 and 12, respectively. Returning to the Grays for the 1939 season, Brancato once again placed among his team’s offensive leaders with 147 hits, 19 doubles, 8 triples, and 197 total bases. Strongly recommeed by Grays manager Marty McManus, who for many years after pointed with pride to Brancato as one of his most prized pupils, the A’s selected the third baseman as a late season call-up.

On September 7, 1939, Brancato made his major-league debut in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park as the A’s starting third baseman. In the second inning, he grounded out to Washington Senators lefthander Ken Chase and couldn’t get the ball out of the infield in two subsequent at-bats. He also committed a fifth inning throwing error that accounted for an unearned run in the Athletics 10-1 loss. Five days later, following two appearances as a defensive replacement, Brancato collected several major-league firsts in a 9-1 win over the St. Louis Browns. In the first inning, he smacked a double against All Star righthander Vern Kennedy and came around to score on left fielder Bob Johnson’s triple. An inning later Brancato delivered an RBI single against right-handed reliever George Gill to plate right fielder Wally Moses. On September 30, on the last day of the season, Brancato got his first home run, a first inning solo shot against Senators rookie righthander Joe Haynes in a 9-5 Athletics loss. He finished his month-long debut with eight hits, seven runs, and six RBIs in his last 22 at-bats. For a player that Connie Mack called “none too fast,” Brancato also collected the first of his five career stolen bases on September 21. 9 Moreover, his defense garnered national attention when Sporting News contributor James C. Isaminger wrote that the youngster was “covering third and doing well.” 10 When the season ended Brancato got permission from Mack to play for the Indoor Phillies in the short-lived National Professional Indoor Baseball League. 11

Initially targeted for assignment to the newly affiliated AA Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League in the spring of 1940, Brancato surprised observers by playing himself onto the parent team. On March 8, during a west coast exhibition tour, Brancato fell a home run shy of the cycle in leading the Athletics to a 10-9 win over the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels. “Brancato maintains his enthusiasm and rapid-fire hot corner play, which have attracted favorable attention,” Isaminger wrote. But the offseason acquisition of 27-year-old rookie infielder Al Rubeling to play third base left Brancato in a shortstop platoon with another promising rookie, Bill Lillard. The platoon lasted just six games into the season when, on April 24 against the New York Yankees, Brancato walked, stole second and then fell victim to the hidden ball trick from veteran shortstop Frank Crosetti. (The future Hall of Famer pulled the trick off a remarkable seven times throughout his long career. The list of victims include fellow greats Joe Cronin and Goose Goslin.) 12 Six weeks passed before Brancato got another start.

On June 6, the “spry young infielder” filled in at third base for Rubeling, who was sidelined with a severe case of food poisoning. Brancato “sock[ed] a single and a double . . . [and] fielded in dazzling style” to lead the Athletics to a 7-4 win over the Detroit Tigers.13 The next day a homer shy of the cycle, he supplied the team’s entire offense with three RBIs was in a 3-2 win against the Browns. Moved to the top of the lineup on June 15, Brancato collected two hits and a career high four RBIs in a 7-4 win over the Cleveland Indians. Six days later, after lifting his average more than 190 points over 15 games, he moved to shortstop for the sidelined Lillard. When Lillard recovered, Mack briefly returned to a platoon before eventually settling on Brancato through the remainder of the season. Unfortunately, the hot bat that earned his return to the lineup chilled considerably over the second half. Then, in a doubleheader against the White Sox on Friday, September 13, Brancato set two dubious milestones: committing a major-league record five errors over the two games, including an AL record-tying three errors in one inning. Brancato finished the season with 23 errors in 414 chances (including six-for-81 at third base), a spotty defensive performance matched by an equally uninspiring .191/.265/.252 slash line in 298 at-bats. Mack, however, was not yet prepared to forsake his young prodigy.

Mack’s faith appeared valid in the spring of 1941 when Brancato performed well during spring training. A month into the regular season, though, only his glovework sparkled. B rancato is “show[ing] the finesse that Mack predicted for him . . . [h]is fielding has been brilliant,” The Sporting News reported. 14 “[H]is work with McCoy in completing double plays is something that Connie would never have dared to dream of before the season got under way [sic].” 15 But Brancato’s offense stunk. Except for a seven-game hitting streak at the beginning of May, he had a .179 average with three extra base hits and seven RBIs in 106 at-bats through the first two months of the season. A changed batting stance around midseason resulted in a more acceptable .252/.331/.311 line in the second half. But Brancato’s focus on improving his hitting appears to have degraded his work in the field. He committed 31 miscues over the last eight weeks of the season in route to a major league leading 61 errors. Through 2016, only Roy Smalley’s 50 errors in 1951 have come close to approaching this for a shortstop. As the season ended Mack hinted that the experiment of using Brancato at short was likely over.

This decision was taken out of Mack’s hands in November when Brancato received notice from the US Army to report to Camp Lee, Virginia, on December 8. This scenario changed the day before he was scheduled to report when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Six days after the attack Brancato enlisted in the US Navy. (Mack, who more than once appears to have served as a surrogate parent after the youngster’s father died in 1939, was present when the 22-year-old enlisted.) Initially assigned to a receiving ship docked at Philadelphia’s League Island near the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, in January Brancato traveled to Quincy, MA, to join the crew of the USS Boston just before the heavy cruiser embarked on a tour of the Pacific. In 1943, Brancato transferred to a submarine base at Pearl Harbor where he “worked in the spare parts department of the ship’s store as a storekeeper second class.” 16 During a later assignment to the island of Tinian in the Mariana Islands “he organized boxing matches in addition to his storekeeper duties. [He served out his enlistment as an] athletic specialist at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.” 17 Throughout his three-and one-half year tenure (more than half of which was spent overseas) Brancato played baseball alongside some of the MLB greats. In June 1944, he teamed with Pee Wee Reese and Johnny Mize to beat a US Army All Star team 9-0 at Oahu’s Chickamauga Park. Playing for Lieutenant Bill Dickey’s squad four months later, Brancato teamed with Dom DiMaggio and Virgil Trucks.

On August 28, 1945, two weeks after Japan announced its surrender, Brancato was discharged from the Navy, and he immediately rejoined the Athletics. On September 1, in his first major league appearance in four years, Brancato was inserted at shortstop as a defense replacement in a 7-1 loss to the Boston Red Sox. Shortly after his return, backup shortstop Bobby Wilkins was sidelined with an ankle injury. Thus Brancato started for the A’s in seven of the 11 doubleheaders the team played over the last month of the season, including a flawless performance during the no-hitter by righthander Dick Fowler on September 9. On September 19, in what proved to be his last major league appearance, Brancato went 0-for-3 and committed two errors (one resulting in an unearned run) in a 3-0 loss to the Red Sox. When the season ended, Mack assured him that the A’s would keep him for the following season. But in late November, while working the night shift at a Philadelphia newspaper, Brancato learned from a co-worker that he had been assigned to Toronto (now a Triple-A team). Mack’s apparent betrayal, especially learned of secondhand, appears to have irreparably damaged the once close relationship between the two.

After spending the first half of the 1946 season with the Maple Leafs, in July Brancato was traded to the Red Sox Triple-A Louisville affiliate. As a utility infielder he helped the team advance to the 1946 Junior World Series. In June 1947, Brancato was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers Triple-A affiliate in St. Paul after their shortstop Bob Ramazzotti suffered a fractured wrist. Assigned to the Texas League’s Fort Worth Cats (Class-AA) after Ramazzotti’s return, Brancato delivered three doubles and a triple in a 12-0 win over the Beaumont Exporters on August 11 before the watchful gaze of Dodgers’ president Branch Rickey. But neither this or any of his subsequent performances ever resulted in a return to the major leagues, and Brancato remained in the Dodgers organization through 1953. In 1948, he returned to the Junior World Series with the St. Paul Saints; three years later, during a June 17 doubleheader against the Columbus Red Birds, Brancato set what was believed to be a dubious American Association record going 0-for-6 against six different pitchers. In 1953, Brancato accepted a demotion to the Class-A Elmira (New York) Pioneers in the Eastern League to try his hand at managing. He inserted himself as a pinch-hitter and occasional third baseman but the team achieved little success. After the season, Brancato retired from Organized Baseball and settled in Upper Darby, a township bordering West Philadelphia. He became a car salesman.

But he couldn’t stay away from baseball for long. In 1959, he launched a six-year career as the head coach for the Saint Joseph Hawks baseball team at Saint Joseph’s University, just three miles west of Philadelphia’s Shibe Park (renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953). Brancato resigned from Saint Joseph’s in August 1964 due to his increased responsibilities as the regional manager for a trucking enterprise. Twenty years later the 65-year-old retired from the work force altogether.18

Brancato had demonstrated a keen interest in business early on. In 1940 he, his brother Joseph, and a third partner opened a sporting goods store in South Philadelphia just blocks from where the Brancato children grew up. “I always had the idea of a store,” Brancato said shortly after the opening. “[T]here was no sports store in our neighborhood where the kids could buy equipment for their teams . . . Of course, I’m something of an attraction to the youngsters, who stand around, asking me one question after another about the A’s . . . But that all goes with the business and I’m glad to tell them.”19

Brancato’s interaction with the neighborhood children in 1940 extended to baseball fans of all ages throughout his life. He enjoyed reminiscing about his baseball experiences and was easily accessible to authors and casual fans. In 1972, Brancato was inducted into the South Philadelphia High School Hall of Fame. Fifteen years later he was similarly honored by the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame, Delaware County Chapter. In 1998, Brancato was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame at Saint Joseph’s University. He was also deeply involved with the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society.

On July 11, 1942, Brancato married Philadelphia native Isabel Frances McCandless. The couple had a daughter and two sons and remained together until Brancato’s passing one month shy of their 70th wedding anniversary.

In the 20-aughts Brancato’s health began to falter, and he was admitted to an assisted living facility in the borough of Mediaon the western outskirts of Philadelphia. On June 14, 2012, 16 days after his 93rd birthday, he died. He was buried at SS Peter and Paul Cemetery in Springfield Township, immediately east of Media.

Two decades after his playing career ended Brancato told author Harrington E. Crissey Jr., “Most current players regard baseball as a business. We enjoyed it and talked about it in our off-hours.”20 Sports in general, and baseball in particular, played an enormous role throughout Brancato’s life. He remained an avid fan until his death.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. The author wishes to thank Brancato’s sons Albert and David for their valuable review and assistance. Further thanks are extended to SABR member Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Notes

1 “Brancato Rates No. 1 More Than One Way,” The Sporting News , June 27, 1940: 3.

2 “Low Quaker Clubs High at First Base,” ibid., May 22, 1941: 5.

3 “Mack Gives ‘Works’ to A’s Inner-Works,” ibid., September 11, 14 (quote).

4 Brancato’s original given name was Angelo. When he died, this was acknowledged on his headstone with “Albert A. Brancato.”

5 “Anne Brancato Wood Historical Marker,” June 17, 1994. Accessed February 6, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2jTIzz5).

6 The Joseph Brancato who played minor league baseball in 1949-50 is a distant cousin.

7 N. Diunte, “Brancato, 93, One of the Last Links to the Major Leagues in the 1930s,” Baseball Happenings. Accessed February 5, 2017 ( http://bit.ly/2ka8zY5 ).

8 “Philadelphia Athletics: Al Brancato,” Accessed February 5, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2lbHR18).

9 “Brancato of Athletics Indoor League Player—Until Mack Kicks,” The Sporting News , November 23, 1939: 1.

10 “Connie Mack Guarding Against Being Caught Short at Short,” ibid., September 21.

11 Fearing injury to his players, Mack often refused to let them play in other professional leagues. In this instance, he appears to have yielded to the request of Indoor Phillies manager and former Athletics team captain Harry Davis.

12 Bill Deane, Finding the Hidden Ball Trick: The Colorful History of Baseball’s Oldest Ruse (Lanham, MD .: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, 2015), 237.

13 “Philly Youth Right at Home with Mack,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1940: 5.

14 “Low Quaker Clubs High at First Base.”

15 “All A’s, Two Phils Providing Thrills,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1941: 8.

16 Harrington E. Crissey Jr., Teenagers, Graybeards and 4-F’s, Volume 2: The American League (Self-Published, 1982), 100.

17 Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime, “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice: Al Brancato,” April 13, 2007. Accessed February 5, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2kBMYLs).

18 Rich Pagano, “Sports Flashback: Pennsylvania Hall of Fame Baseball Player Al Brancato,” Delaware County News Network, March 22, 2013. Accessed February 12, 2017 ( http://bit.ly/2lE3W9U).

19 “Al Brancato, Shortstop of A’s, Runs Own Sports Store at 22,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1940: 16.

20 Crissey, Teenagers, Graybeards and 4-F’s , 102.

Full Name

Albert Brancato

Born

May 29, 1919 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

June 14, 2012 at Media, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.