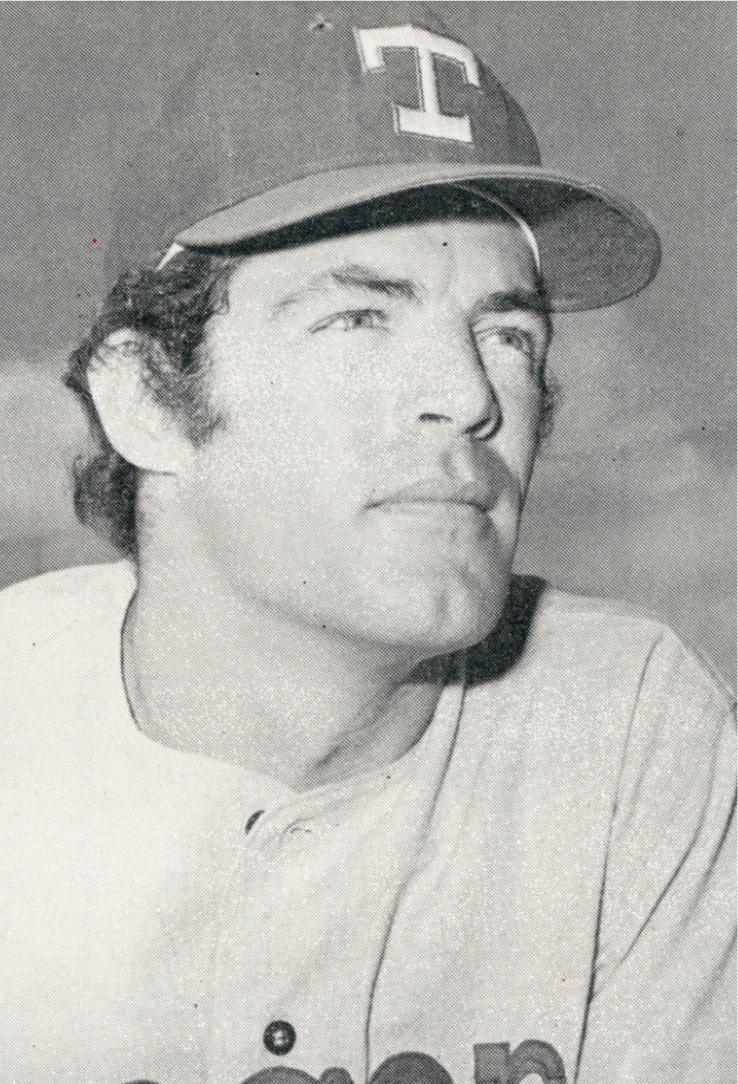

Jim Driscoll

James Bernard Driscoll was born in the midst of World War II on May 14, 1944, in the town of Medford, Massachusetts, about three miles northwest of downtown Boston. He was the second-born of Joseph and Kathleen (O’Keefe) Driscoll, longtime residents of the Boston area. Joseph and Kathleen would ultimately produce a family of nine children – six boys and three girls. Joe Sr. was a railroad man for more than 30 years, working as a conductor on New York Central Railroad trains out of Boston. His mother, Kathleen, became a registered nurse and worked for the physician who pioneered hip-replacement surgery, Dr. Otto Aufranc of New England Baptist Hospital in Boston.

James Bernard Driscoll was born in the midst of World War II on May 14, 1944, in the town of Medford, Massachusetts, about three miles northwest of downtown Boston. He was the second-born of Joseph and Kathleen (O’Keefe) Driscoll, longtime residents of the Boston area. Joseph and Kathleen would ultimately produce a family of nine children – six boys and three girls. Joe Sr. was a railroad man for more than 30 years, working as a conductor on New York Central Railroad trains out of Boston. His mother, Kathleen, became a registered nurse and worked for the physician who pioneered hip-replacement surgery, Dr. Otto Aufranc of New England Baptist Hospital in Boston.

Jimmy grew up deeply immersed in the world of Boston sports. His father supplemented his income while satisfying his love of baseball as an usher at Fenway Park. His longtime access to Fenway Park enabled Jimmy to experience major-league sports and its players close-up. Joseph once asked Ted Williams to pose with Joe Jr. and Jimmy for a photo prior to a Red Sox game in 1948. The boys, 5 and 4 years old at the time, were posed on either side of the majestically tall man who had hit .406 in 1941. Jimmy retained many such rich memories of his dad and Fenway Park. He often told of how his father, when the Fenway Park gates opened before a game, Joe Sr. would stand by the Red Sox dugout and cry out to the other ushers, “They’re open!” Tom Grieve, a teammate of Jimmy’s on the 1972 Rangers, remembered fondly how delighted his teammates were when Jimmy would emulate his father by crying out, during batting practice, “They’re open!” as the fans began to enter the ballpark.1

Joe Sr. often used his friendship with ushers at other venues, particularly Boston Garden, to get his family (and sometimes their friends) into events without tickets. He would have them gather an inconspicuous distance from a gate while he engaged in conversation with the gate usher. Upon “getting the high sign” from his father, the youngsters were to enter through the gate and “not look back.” This procedure served the Driscoll family well over the years, exposing them to many baseball, hockey, basketball, and football games. As the boys grew older, it would be their turn to be the attraction at local venues.

Jimmy’s older brother, Joe Jr., was the first to draw attention to the Driscoll family. In the spring of 1961, he broke a 68-68 tie with time expiring in the state high-school championship basketball game by sinking the game-winning basket from beyond the half-court line. The game was played before a packed house of 13,909 in the Boston Garden. In the fall of that year, Jimmy quarterbacked his Arlington High School football team to the state championship. In the spring of 1962, Jimmy’s senior year, he tied baseball’s Tony Conigliaro for the state high-school leadership in home runs. Other brothers, in the years to follow, would quarterback their team in a Sun Bowl football game; play in the College World Series; and umpire, calling balls and strikes, in the College World Series championship game that Roger Clemens pitched for the winning University of Texas Longhorns.

Jimmy performed well at football and basketball, but baseball was to be what shaped his future. An infielder, he was followed, starting in his sophomore year, by an ever-growing number of major-league scouts attending his high-school games. This attention culminated on graduation night in early June of 1962. His graduation ceremony began at 7:00 P.M. and by 10:30 he had signed his first professional baseball contract. (This was prior to today’s amateur draft so teams had to compete for prospective talent by offering bonus money with the contract.) His father had the scouts line up outside his home, giving each of them 20 minutes to present their offer. Jeff Jones of the Milwaukee Braves made the winning presentation and obtained young Driscoll’s signature on a minor-league contract in exchange for a $10,000 bonus.2

In high school, Driscoll played the infield, primarily shortstop. The left-handed hitter, at 18 years old, slightly built at 5-feet-11 and 175 pounds, physically resembled the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Pee Wee Reese. As a result, he was often called “Pee Wee” by his teammates.

The Braves assigned Driscoll to Dublin, Georgia, of the Class-D Georgia-Florida League, managed by the snarky, seasoned Bill Steinecke, who managed in the lower minors for the Braves organization from 1937 through 1964. A player-turned-author named Pat Jordan, in his book A False Spring, described Steinecke as profane and crude in language and behavior but effective as a baseball manager.3

The 18-year-old Driscoll felt he was in another world as he set about to play organized ball in this small, rural Georgia town amid the civil rights strife of the early 1960s. He recalled the strangeness and puzzlement of seeing “White Only” signs, and blacks having to sit in a segregated section in right field. Adding to the strangeness of his new surroundings was a peculiar and puzzling encounter with Steinecke, awaiting Jimmy after a 10:00 A.M. workout at the Dublin ballpark.

In the lower minors, morning workouts were common to instruct the young players about the subtleties of play such as footwork around second base during a double play or infielder-outfielder communication for popups. Driscoll, having arrived in Dublin after the third inning of the team’s game, did not suit up with the team, so the next morning’s workout was his first uniformed activity with his new club. After the workout, the players headed to the showers. Jimmy described an event that he believed to be either an initiation or an act of unprecedented insensitivity. At the time of a 2016 interview4, he still hadn’t decided which. As he described it:

The showers next to the locker room was a small area with only five shower heads. In their haste to dress and leave for lunch at least 10 players, maybe more, gathered under those five shower heads, myself included. This scrum of naked men, elbowing and shoving each other, while vying for the most effective position under the directed water flow, got even more congested when the manager, Bill Steineke, joined his wet and soap-covered team in the disorderly fray beneath each of the limited number of shower heads. You must understand that Steineke was a consummate tobacco chewer. Not attracted by the neatly packaged and processed name brands like Red Man or Beech-Nut, he preferred chewing portions of cigars. Inserting a cigar in his mouth, he would bite off a significant portion, beginning to chew as portions of tobacco leaf fell from his lower lip because his mouth could simply not contain all the tobacco he had ungracefully shoved into the ever-growing bulge in his right cheek. Such was the condition of Steiny’s mouth as he stood within a foot of my presence. Water, flowing over his face, slightly discolored the tobacco juice dripping onto the floor of the shower and upon his hairy chest. Stepping away from the direct flow of the shower head, he turned his face to mine and began to speak. Simultaneously, with the words leaving his mouth, was the fine spray of tobacco particles and juice which settled upon my face. At the same time, I became conscious of a continuous stream of warm water falling, thigh high, upon my left leg. The stream of water was hitting my leg at an angle which made me think it was not from the shower head. Turning my head downward to avoid the tobacco spray, I heard the words, ‘Welcome to pro ball kid! You’re going to love it here!” While appreciating the welcome message, I was disheartened to see he was urinating upon my leg. Welcome indeed!

Despite the disturbing nature of his first day in pro ball and the other cultural adjustments required of the schoolboy from Boston, he adapted to baseball among the cotton fields and played in 48 games while hitting a respectable .275. However, this was to be his only year as property of the Milwaukee Braves; in November he was selected by the Kansas City Athletics in the first-year player draft.

The first-year player draft was instituted by the major-league clubs at the 1958 winter meetings as a way to save themselves from the price war for young baseball talent that was developing after World War II.5 Bonuses were becoming exorbitant and were even exceeding the salaries of some major-league players. At the 1964 winter meetings the rule was abandoned in favor of the amateur draft. In 1962 Driscoll was one of the 45 players drafted.

Driscoll labored long in the Kansas City/Oakland A’s minor-league system, spending two years at Class A, two years at Double A, and four years at Triple A. It was a long journey but after eight years, at age 26 he got the call. It came on the night of June 16, 1970. Playing for the Triple-A Iowa Oaks (Des Moines), Driscoll doubled off the right-field wall to drive in the game-winning run. This was a special occasion for him because four of his brothers were there to see him play. They had traveled to Omaha, Nebraska, to see their brother Mark play in the College World Series for the University of Arizona. After Arizona was eliminated from the tourney, they traveled to Des Moines to see Jimmy play. After the game they bunked in Jimmy’s apartment. Around 7:30 in the morning, Jimmy got a call from Charlie Finley, owner of the Oakland A’s, who asked, “How would you like to be wearing a pair of white shoes in Detroit tonight?”6 The brothers flew to Detroit and took a cab to Tiger Stadium. Arriving about 5 P.M., Jimmy found a locker with a uniform bearing the number 21 with DRISCOLL on the back of the jersey, as well as a pair of white shoes as Charlie Finley had promised. Less than 24 hours from his walk-off double, Driscoll was in uniform for the Athletics game in Tiger Stadium before a crowd of 12,541 that included his five brothers. He would never forget the night of June 17, 1970.

The 1970 Oakland A’s were building the foundations of the team that would gain a playoff spot in 1971, then win the next three World Series (1972-74). Driscoll had been called up from Iowa after hitting a solid .303 in 76 games. This performance came on the heels of a .286 season in 1969.

From the bench, Driscoll watched his team take a 1-0 lead off Tigers lefty Les Cain in the top of the first. Catfish Hunter, however, could not hold the lead, failing to get anyone out in the bottom of the second. The Tigers scored five runs in the inning off Hunter and reliever Diego Segui. The A’s regained the lead in the fourth only to see the Tigers retake the lead in the fifth. With the Tigers leading 8-7 in the top of the seventh inning, the A’s manager, John McNamara, sent Driscoll up to pinch-hit for second baseman Tony La Russa.7 Driscoll waited in the on-deck circle while Rick Monday batted. Monday singled to right field. As Driscoll strode to the plate, Bill Freehan, the Tigers catcher, gave him a puzzled glance, then trotted to the mound followed soon by the Tigers pitching coach. Driscoll thought they were probably discussing how to pitch to this nameless guy no one knew. After the umpire broke up the meeting at the mound, Driscoll positioned himself in the batter’s box. Before seeing a pitch, he watched as Tom Timmermann, the Detroit pitcher, threw wildly to first base and Monday went to second base, in scoring position as the tying run. Nervous but focused, Driscoll dug in at the plate and awaited the first pitch. It was an inside fastball that he turned on quickly, hitting it solidly. Its path was a long, high arc down the right-field line toward the covered bleachers of Tiger Stadium, but drifted foul.

Returning to the batter’s box, Driscoll thought to himself, “It might not be official but I know I hit the first pitch I saw in the major leagues for a home run!” In a few moments the inning ended with Driscoll lifting a fly ball to Mickey Stanley in center field for the third out.

He played in another 20 games for the A’s that year, mostly in pinch-hitting roles, but the season was to include even more special moments and highlights for Driscoll to remember. On Sunday, July 19, the A’s were in Boston to start a two-game series with the Red Sox. There was some local media notice of Jimmy Driscoll, a local boy, coming into town with the A’s. He had permission from manager McNamara to stay with his folks rather than with the team at the hotel. Driscoll said he had 91 tickets held at the Fenway Park box office for family and friends. (Each player is granted 10 tickets to pass out for any game. Driscoll “borrowed” tickets from teammates to accumulate 91.

While Driscoll visited with his family, his father asked if he was starting the first game. Jimmy said he wouldn’t know until right before game time. Upon arrival at Fenway Park on Sunday morning, he learned that McNamara had put him in the starting lineup at second base. With his very proud mom and dad sitting in front-row box seats by the A’s on-deck circle, he went 2-for-4 against Ray Culp in a losing effort in the first game of the series and 0-for-3 in a 3-2 win for the A’s in the second game. Driscoll recalled that he made a great play in the bottom of the first inning of the second game, going hard to his left between first and second base to rob Carl Yastrzemski of a hit. Yastrzemski, with a batting average of .3286 (rounded off to .329) lost the batting title to Alex Johnson of the California Angels (.3289, also rounded off to .329). Had Driscoll not made that play, Yastrzemski would have won the batting title.

At the end of that 1970 season, Driscoll experienced another special moment. In the last three games of the season, he got a taste of being a regular in the big leagues. Closing out the year against the Milwaukee Brewers, he started all three games at shortstop, replacing an injured Bert Campaneris.

In the first game of that series, on September 29, Driscoll, batting eighth in the A’s lineup, went 1-for-3 with a walk. His hit was a solo home run off the Brewers’ Al Downing, who four years later would be famous for his association with Hank Aaron’s 715th home run,8 to lead off the bottom of the fourth inning and put the A’s ahead, 3-2. The A’s, with Catfish Hunter pitching a complete game, won 4-3. Driscoll laughingly claimed, “Hank Aaron has nothing on me. Downing is on my list too!” This was his only major-league home run.

Whether it was the change in management (Dick Williams replacing McNamara as manager) or other reasons, such as too many left-handed batters, the exact reason will never be known, but the net of it all was Driscoll being returned to the Iowa Oaks for the 1971 season. Then, on June 15, 1971, the Washington Senators purchased his contract from the A’s and assigned him to another American Association club, the Denver Bears. He remained in the American Association for the rest of that year, batting a combined .262 with 15 home runs.

The 1971 season was a highlight in Driscoll’s minor-league career. He was named to the American Association All-Star team, and the Bears won the American Association championship, and played the Rochester Red Wings (champions of the International League) in what was then called the Junior World Series. Driscoll recalled the experience in an article in 1974 in the Denver Post: “We had to play all seven games in Rochester because of construction in Bears Stadium, Driscoll said. We came close to winning. We were down 3-1 and came back before Rochester won in the seventh game. We had some rain postponements, and it seemed as if we were there forever.”9

Driscoll batted .423 with one home run, four doubles, and five RBIs in the Junior World Series.10 That success earned him a trip to the 1972 spring-training camp of the Texas Rangers, the former Washington Senators.

Irv Moss described Driscoll’s first meeting with his new manager: “On his first day with the Rangers, Driscoll showed Ted Williams a picture taken at Fenway Park of the former Boston Red Sox slugger and a 4-year old boy. It was Driscoll some 24 years before the reunion.”11 Driscoll said that Williams was pleased he had shown him the photograph. Ted then autographed the photo with these words, “To Jim: The effort paid off. My regards, Ted Williams.”

Hitless in 20 plate appearances for the Rangers, Driscoll was sent down to Denver in late May, never again to see action in the majors.

He played in his last major-league game on May 26, 1972. Third baseman Dave Nelson was hit by a Bert Blyleven pitch and had to leave in the third inning of the game. Driscoll entered the game as his replacement. Blyleven, on his way to a complete-game five-hit shutout, retired Driscoll in each of his three plate appearances that day, a strikeout in the fourth, a fly ball to right in the seventh, and a popup to shortstop in the ninth. On his last plate appearance in the major leagues, Driscoll made the 27th out to seal a 7-0 home victory over the Rangers by the Minnesota Twins before 7,383 witnesses. In his brief stay with the Rangers, Driscoll played in 15 games and reached base just twice, both on walks, never scored, and finished 0-for-18 at the plate.

In December 1972 Driscoll and catcher Hal King were traded by the Rangers to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Jimmy Merritt. Invited to 1973 spring training, though under a minor-league contract, Driscoll got a lot of playing time at second base in most of the Reds’ exhibition games. Hitting over .400 with a couple of home runs, he was beginning to feel good about his prospects of sticking with the Reds, who were just then forming the core of Sparky Anderson’s “Big Red Machine” that dominated the mid- to late ’70s. But it was in a game near the end of spring training that Driscoll began to see the direction of his major-league career:

“I don’t remember who hit it but a towering fly ball between first and second was coming down in short right field. A 23-year-old rookie named Ken Griffey (Sr.) was playing in right field. I was going out and Griffey was coming in. Not hearing him say anything and my eyes focused upon the descending ball, just as the ball hit my glove, Griffey hit me. Falling to the ground, feeling conscious but breathless, I held the ball for the third out. As we both lay sprawled upon the ground, I could see a concerned Sparky Anderson, Alex Grammas, and the trainer racing from the dugout toward us. Without so much as a glance or word for me, they all hurdled over my prone body to get to Griffey, also laying on his back. I struggled, unnoticed by all, to get up and walk back to the dugout unassisted. It was obvious to me where I fit into this organization. True to my feelings, the next day I got notified that Sparky Anderson wanted to see me. He told me I had played well enough to make the club but he had too many left-handed batters on the club. I was being sent down to Indianapolis.”

After two disappointing seasons with Triple-A Indianapolis, (.226 and .206), Driscoll caught on with the Houston Astros’ Triple-A team for the 1975 season. Ironically, he found himself in Des Moines playing for the Iowa Oaks. Hitting .205 for the year, he retired from professional baseball after the 1975 season. He was 31 years old.

After baseball Driscoll found success as an area scout for the Baltimore Orioles, while living in the Phoenix area for over 30 years. At his first game as a scout, another scout who was sitting next to him introduced himself, “Hi! I’m Joe Maddon. I’m a scout with the California Angels.” They became good friends, with Jimmy being asked by Joe to be the best man at his wedding.

Upon retirement from scouting, Driscoll returned to New England in 2010, and currently lives in New Hampshire with his wife, Caroline. They have one daughter, Heather, who teaches botany at the University of New Hampshire. Driscoll is active in his church and enjoys fishing and golf.

This article was published in “The Team That Couldn’t Hit: The 1972 Texas Rangers” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Refrerence.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with Tom Grieve, November 12, 2015.

2 Irv Moss, “’71 Season Memorable for Jimmy Driscoll,” Denver Post, May 1, 2014.

3 Pat Jordan, A False Spring (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1975), 114-117.

4 Unless otherwise noted, all direct quotations are from an author interview with Jim Driscoll on April 24, 2016.

5 Cliff Blau, “The Real First Year Draft,” Baseball Research Journal 39, No. 1 (2010).

6 Oakland in 1970 was experimenting with unconventional, colorful uniforms that included white shoes in place of the more conventional black shoes.

7 Hall of Famer Tony La Russa, whose playing career in the majors and minors spanned 16 years (1962-1977), was a weak-hitting infielder whose career major-league batting average was .199 in 203 plate appearances in 132 games. After being released by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1977, he took the job of field manager for the Chicago White Sox at the end of the 1979 season. This began one of the most successful managerial careers in major-league history, spanning 33 years, over 5,000 games, six pennants and three World Series championships with three different teams (White Sox, A’s, Cardinals). La Russa was inducted into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 2014.

8 Al Downing, on April 8, 1974, while pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers in a game against the Atlanta Braves, in the fourth inning of that game gave up the 715th home run of Hank Aaron’s career. This broke Babe Ruth’s long-standing record for career home runs.

9 Moss.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

Full Name

James Bernard Driscoll

Born

May 14, 1944 at Medford, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.