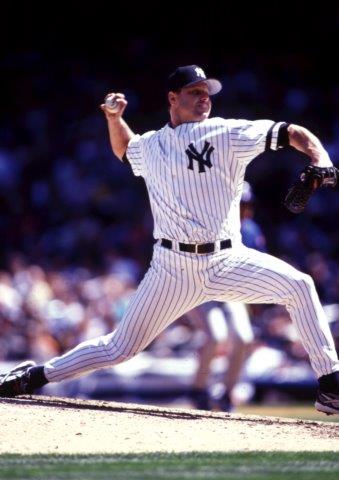

Roger Clemens

Roger Clemens’ last major-league start, on October 7, 2007 — for the New York Yankees against the Cleveland Indians, the very team against which he had made his major-league debut in May 1984 — ended with him limping off the mound after only 2⅓ innings with a hamstring injury. Clemens had already allowed the Indians one run in each of the first and second innings, and, after facing two batters in the top of the third, he could pitch no more. He was charged with a third run, though the Yankees came back to win the game 8-4 for their lone victory in this American League Division Series. Such an ending is not what a movie screenwriter would have scripted as the final chapter of “Rocket’s” 24-year career, but at least one element of Clemens’ last appearance was storybook in character: He struck out the final batter he faced, Indians catcher Victor Martinez.

Roger Clemens’ last major-league start, on October 7, 2007 — for the New York Yankees against the Cleveland Indians, the very team against which he had made his major-league debut in May 1984 — ended with him limping off the mound after only 2⅓ innings with a hamstring injury. Clemens had already allowed the Indians one run in each of the first and second innings, and, after facing two batters in the top of the third, he could pitch no more. He was charged with a third run, though the Yankees came back to win the game 8-4 for their lone victory in this American League Division Series. Such an ending is not what a movie screenwriter would have scripted as the final chapter of “Rocket’s” 24-year career, but at least one element of Clemens’ last appearance was storybook in character: He struck out the final batter he faced, Indians catcher Victor Martinez.

In spite of the abrupt end to Clemens’ evening and career, as he left the mound, it seemed a certainty that he would be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, as soon as he passed the five-year waiting period for eligibility. Few pitchers in the history of baseball could boast anything near to his accomplishments: a record seven Cy Young Awards, 354 victories, 4,672 strikeouts, seven-time ERA leader with a career 3.12 ERA, six-time 20-game winner, five-time strikeout leader, 46 shutouts in the era of relief specialists and closers, and two-time World Series champion. He was too much of a polarizing figure in his career to exceed Tom Seaver’s record of being named on 98.8 percent of the Hall of Fame ballots, but he seemed certain to be a first-ballot selectee.

On December 13, 2007, little more than two months after Clemens’ final Yankees start, doubt was cast over his future enshrinement among baseball’s immortals when he was mentioned repeatedly in the Mitchell Report on the use of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball. In the years following the report, Clemens spent almost as much time in courtrooms as he spent on pitcher’s mounds during his career. By the time his first year of eligibility for the Hall of Fame arrived in January 2013, he was named on only 37.6 percent of the ballots and, in his second year, that number declined to 35.4 percent while two of his contemporaries and fellow members of the 300-win club, Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine, were elected.

Clemens’ life is the tale of a fanatically driven man who worked hard to achieve his dream of stardom and attained the pinnacle of success. Jorge Posada, Clemens’ catcher with the Yankees, was complimentary when he said, “The only thing he wants to do is just win.”1 Cito Gaston, Clemens’ manager with the Toronto Blue Jays until he was fired toward the end of the 1997 season, intended no such praise when he commented, “It’s all about him, nobody else but him.”2 Clemens’ ambition gained him both fans and detractors, helped him to achieve massive success, and ultimately contributed to his fall from grace.

William Roger Clemens was born on August 4, 1962, in Dayton, Ohio, the fifth child of Bill and Bess Clemens. He was only 5 months old when his mother took her children and left his father, with whom he claims to have spoken only once in his life, when he was 10 years old. Less than two years later, Bess married Woody Booher, whom Roger looked up to as a real father. But he became fatherless again at the age of 8 when Booher died of a heart attack.

While his mother provided Roger with an example of the work ethic he would adopt by laboring at several jobs to support her children, he came under the tutelage of his older brother Randy, whom he idolized. In high school Randy was a shortstop on the baseball team, the star shooting guard for the basketball team, and the king of his senior prom, leading Clemens to admit, “While I was growing up, Randy was the star as far as I was concerned.”3 Though the two brothers have become estranged, Randy’s influence was immense as he “instill[ed] in his brother a simple philosophy: Either you’re a winner or you’re a failure.”4 It was a mantra that caused Clemens to question at times whether he was good enough to become the star athlete that both of them wanted him to be.

While Clemens’ baseball career dwarfs his brother Randy’s high-school athletic exploits, his initial attempts to emulate his elder sibling were less than encouraging. He played baseball, basketball, and football, but distinguished himself in none of these sports. In fact, the only notable event from his youth baseball exploits was that he split starts for his 1977 squad with Kelly Krzan, who was the first girl in Ohio to play on a boys’ Little League team.

By the time Clemens was 15 and a high-school sophomore, Randy had married and moved to Sugar Land, Texas, a suburb 20 miles southwest of downtown Houston. Randy had failed to achieve athletic stardom of his own largely due to the development of a substance-abuse problem, but he now wanted to guide his younger brother’s athletic career. After the two brothers received their mother’s permission, Ohio-born-and-raised Roger Clemens made the sojourn to Texas, the state with which he has become identified.

Clemens enjoyed initial success by amassing a 12-1 record and helping Sugar Land’s Dulles High School win a district title, but Randy was plotting a move to more competitive fields. After watching a tournament game between two of the Houston area’s premier high-school teams, Bellaire and Spring Woods, Clemens decided that he wanted to play for the latter team. Bess Clemens had moved to Houston now as well, and she made sure that her son’s wish was granted.

The time spent at Spring Woods High School was a mixed blessing: Clemens played for a coach, Charlie Maiorana, whom he credits for much of his knowledge about mechanics and conditioning, but he spent his junior year seeing little action on a team with two of the state’s best pitching prospects. His determination showed as he became known for his workout regimen, especially his running, and he had his turn as Spring Woods’ number one starting pitcher during his senior year. Still, at that point in his life, the player who came to sit at number three on the major-league strikeout list still threw too softly to draw any notice from either professional or college scouts.

As a favor to Clemens, Maiorana called a colleague, Wayne Graham, the new coach at San Jacinto Junior College, to ask if he could pull any strings to get Clemens to his desired destination, the University of Texas in Austin. Graham could not accomplish that feat, but he did offer Clemens a scholarship to San Jacinto, which is where Clemens’ fortunes were reversed. The failure to achieve high-school stardom resulted in the season that launched Clemens on the path to professional greatness.

The year 1981 was Wayne Graham’s first season to coach at any college level, but he has become a legend by guiding San Jacinto to five national junior-college championships in six years (1985-1990) – a feat that earned him Collegiate Baseball Magazine’s Junior College Coach of the Century Award – and leading Houston’s Rice University to the NCAA College World Series Championship in 2003. What Graham did with Clemens – turning a soft-tossing youth into a flamethrower – was an equally impressive accomplishment. He preached to Clemens that he needed to finish hard on his pitches or he would never have a chance to realize his dream of pitching in the major leagues, a message Clemens took to heart as he finished his sole season at San Jacinto with a 9-2 record while the college won the Texas Junior College Athletic Association championship. His coach’s assessment was that “Roger began the year as one of the guys, and he ended it as an ace.”5

Graham anticipated that Clemens would remain at San Jacinto for a second year, an expectation that was buoyed when Clemens turned down an offer from the New York Mets, who had selected him in the 12th round of the 1981 draft. Clemens went through the motions of throwing for Mets manager Joe Torre and pitching coach/legend Bob Gibson at Houston’s Astrodome, but he had other plans in mind. He had been contacted by University of Texas Longhorns coach Cliff Gustafson, who was now interested in the improved pitcher. The opportunity to play at Texas had been Clemens’ dream, and he pounced on it; however, he failed to contact Graham about his decision and alienated the man who had placed him on the road to stardom.

Clemens fulfilled expectations at Texas, although there were some hiccups along the way. The 1982 Longhorns began their season with a 33-game winning streak that was one win shy of tying the NCAA record. Clemens, who had begun the campaign 7-0, pitched in game number 34 but lost 4-3 to the University of Houston. It was later revealed that he had bursitis while pitching that game, and he missed the next two weeks of the season. He finished 12-2 with a 1.99 ERA, but Texas was eliminated from the College World Series by Wichita State.

The Longhorns suffered under the burden of high expectations in 1983 and plodded through an up-and down season. At one point, the driven Clemens became so frustrated by his personal mound setbacks that he was ready to quit the team, an example of the toll that the insecurity caused by Randy Clemens’ “winner or failure” mentality took on him. While he was not yet a polished pitcher, he still demonstrated great potential. Houston Astros scout Gordon Lakey reported that Clemens’ delivery was not compact enough, but he believed it could be helped and that Clemens would develop more leg drive and become a power pitcher.6 Chicago White Sox scout Larry Monroe’s report echoed that of Lakey as he wrote of Clemens: “Delivery is fluid but does not use body at all. Should be easily improved and no reason why he shouldn’t be in low 90’s. I’m surprised he doesn’t have shoulder problems from standing up and just throwing. Some bend in legs and drive to plate would help velocity, life, and location.”7 Both scouts projected Clemens as a likely second-round draft pick. Owing to rare encouragement from the usually gruff Gustafson, Clemens persevered – he went 13-5 with a 3.04 ERA – and the Longhorns survived their inconsistency to make a return trip to the College World Series.

Before Clemens took the mound for his start against Oklahoma State in the College World Series on June 6, the Boston Red Sox selected him as the 19th player chosen in the major-league draft, a circumstance about which he said, “I was completely surprised. As far as I was concerned, Boston was a foreign country.”8 Five days after defeating Oklahoma State, Clemens capped his Texas career with a complete-game 4-3 victory over Alabama in the College World Series Championship Game to put himself and his team on top of the collegiate baseball world before he departed Austin for Boston, having now been signed by Red Sox scout Danny Doyle. Of course, Clemens did not make it to the parent club straight out of college, but he did take the fast track through the Red Sox’ minor-league system where he already exhibited character traits that became hallmarks of his career.

His first stop was with the Winter Haven Red Sox of the Class-A Florida State League, for whom he went 3-1 with a 1.24 ERA in four starts and where he established his reputation for pitching inside to hitters. Two days before his final Winter Haven start, Clemens had taken umbrage at the Lakeland Tigers’ Ronald Davis taking out his Red Sox (and ex-University of Texas) teammate Mike Brumley at second base, a play on which Brumley was injured. Clemens pitched a 15-strikeout shutout against Lakeland in which he also retaliated for Brumley’s injury by hitting Davis in the head in his first at-bat. Clemens claimed – as most pitchers do – that he had only wanted to brush Davis back and that the pitch had gotten away from him; however, he also claimed that he was prepared to fight, something for which Davis was in no condition as he collapsed and was taken to a hospital.

The split opinion among baseball observers as to whether Clemens merely pitched inside or was a headhunter mirrors the split in opinion about his character in general. Few players thought poorly of Don Drysdale or Nolan Ryan for pitching close inside, but these two pitchers were held in high regard while Clemens was often considered arrogant. Clemens fanned the flames of this negative reputation by both his actions and his words, never more infamously so than after winning the 1986 American League MVP Award. When informed that no less a luminary than Hank Aaron had asserted that pitchers should not receive the MVP, he retorted, “I wish he was still playing. I’d probably crack his head open to show him how valuable I was.”9

After his debacle-marred gem, Clemens was promoted to the New Britain (Connecticut) Red Sox of the Double-A Eastern League and amassed a 4-1 record with a 1.38 ERA in seven starts, but he also continued to draw controversy. In the team’s first-round playoff series, Reading Phillies manager Bill Dancy protested that Clemens was using a glove that had writing all over it and claimed that it was distracting. The home-plate umpire ordered Clemens to use a different glove – an order the pitcher complied with – but he began to curse at Clemens due to the grief he was getting from New Britain’s bench. Clemens charged the umpire but stopped short of any physical contact. Instead, he calmed down, borrowed a teammate’s glove, and proceeded to dominate Reading. Charging umpires became another Clemens trait as his career progressed, but calming down did not. As he accumulated successes, his “winner or failure” mentality and its resultant insecurity morphed into hypercompetitive intensity on and off the mound.

New Britain dispatched the Phillies and faced the Lynn Sailors for the championship, which they won when Clemens pitched a 10-strikeout shutout in Game Four. After he had breezed through two levels of the minor leagues and won his second championship in three months, Clemens’ baseball future looked bright. His personal life became equally so when he began to date Debra Lynn Godfrey, whom he had known in passing at Spring Woods High School, in the offseason. Godfrey was a fellow fitness fanatic who twice auditioned for the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders squad, and the two of them worked out together regularly. They became engaged in May 1984 and were married in November of that year.

Before his engagement to Godfrey, Clemens made one final stop on his way to Boston. He took part in spring training with the parent club in the familiar surroundings of Winter Haven, Florida, but ended up being assigned to Pawtucket of the Triple-A International League to begin the season after posting a 6.60 ERA in Grapefruit League games. Clemens did not allow his disappointment to keep him from excelling at yet another level as he posted a 1.93 ERA in 46⅔ innings for Pawtucket. Enough was enough and, on May 11, 1984, Roger Clemens was officially called up by the Boston Red Sox.

On Tuesday, May 15, 1984, Clemens made his major-league debut against the Indians before a mere 4,004 fans at chilly Cleveland Stadium and learned that minor-league success does not always carry over instantly to the majors. He received no decision after surrendering 11 hits, three walks, and five runs (four earned) in 5⅔ innings, but what was alarming was that Indians baserunners had swiped six bases against him because, in the words of his catcher, Gary Allenson, “(a)t that point, he had no real concept of keeping opposing runners in check.”10 In his next start, against the Minnesota Twins on May 20, he pitched seven strong innings to earn his first major-league victory.

The remainder of Clemens’ rookie season was not as memorable as the one put together by his National League counterpart, Dwight Gooden of the New York Mets, who finished with a 17-9 record and easily won the NL Rookie of the Year award. Clemens was up and down from start to start and later conceded that some people were beginning to question whether he might fall into the same category as David Clyde, the 1970s poster boy for young pitchers who had been rushed to the major leagues too quickly. That fear was put to rest by a 15-strikeout performance against the Kansas City Royals on August 21, but soon a new specter – that of injury – arrived to haunt the Red Sox and their fans. In his final start of the season, on August 31 against the Indians, Clemens registered seven of 11 outs by strikeout and then exited the game with a strained tendon in his right forearm. Though the injury was minor, Clemens was shut down for the year and finished a solid but unspectacular rookie campaign at 9-4 with a 4.32 ERA.

Clemens endured nagging injuries on his way to a 7-5/3.29 sophomore campaign in 1985. The low point of his season came on July 7 when he could not make his scheduled start against the California Angels due to what he described as “[. . .] an intensely sharp pain, as if someone stuck a knife in the back of my shoulder.”11 Clemens’ early-career insecurity came to the fore again as he engaged in a clubhouse meltdown in Anaheim that day, and his fear of failure caused him to break down in tears while repeatedly asking, “Why me?” The next day he was placed on the 15-day disabled list due to shoulder inflammation and, though he returned to the rotation, he never recovered fully that year. On August 30 surgeon James Andrews removed a small piece of cartilage from Clemens’ right shoulder in a 20-minute procedure. Clemens spent the offseason learning new exercises to strengthen his shoulder and waited for the 1986 season to come around.

The Red Sox started out slowly in 1986, but Clemens overcame his spring-training fears about his rehabilitated shoulder and charged out to a 3-0 record with a 1.85 ERA. His fourth start provided the harbinger of things to come as April 29, 1986, became the night on which Roger Clemens vaulted himself to stardom. Facing a free-swinging Seattle Mariners team that had struck out 166 times in 19 games, he turned in a record-setting performance by striking out 20 batters in a nine-inning, complete-game effort at Fenway Park. Clemens began the game in form by brushing back his former college teammate and role model Spike Owen with his second and third pitches of the night. Afterward, he denied throwing at Owen, but a conflicting account exists in which former Longhorns teammate Mike Capel dared him to plunk Owen on the day before the game.

Whatever the truth about Clemens’ intent, the tone for the game was set and the Mariners were baffled for all but one pitch. Gorman Thomas launched Clemens’ lone mistake for a solo home run and a 1-0 Mariners lead in the top of the seventh inning and, for a moment, it looked as though Clemens’ brilliance might be for naught. Fortunately for Clemens and the Red Sox, Dwight Evans hit a three-run homer in the bottom of the inning for the final 3-1 margin of victory. From that point on, Clemens struck out four more batters to reach the record-breaking total of 20. He became an instant superstar and fulfilled a dream he claimed to have had when he was 12 by making the cover of Sports Illustrated’s May 12, 1986 issue, which carried the headline “Lord of the K’s.”12

After an 11-strikeout victory at Baltimore on June 27, Clemens was only the fifth pitcher in major-league history to start a season 14-0. He suffered his first loss on July 2 against the Toronto Blue Jays, but his 15-2 first-half record led Kansas City manager Dick Howser to name him the American League’s starter in the All-Star Game, which would be held in his adopted hometown of Houston. The Red Sox, meanwhile, were in first place in the AL East with a 56-31 record and a seven-game lead at the break.

There was, however, a downside that accompanied all of this success, and it involved his relationship with the media and its burgeoning demands on his time. According to Clemens, “The attention I enjoyed and appreciated at first after breaking the strikeout record soon became stressful.” He claimed that the press did not realize “how I needed to stay on my program and work.”13 For their part, the reporters began to perceive Clemens as alternately aloof or difficult, depending upon whether or not they could get any worthwhile quotes from the new star. Clemens correctly conceded that this period was “the first time I experienced some problems with the media,”14 but it would not be the last.

The media crush of an All-Star Game that matched Clemens and fellow fireballer Dwight Gooden as the starters did not deter him from turning the event into yet another showcase for his talents. While Gooden surrendered two runs in three innings of work, Clemens retired all nine NL batters he faced, struck out two, and did not allow a single baserunner, a performance that earned him the game’s MVP award. His newfound stardom also birthed a new arrogance that surfaced in the second half of the 1986 season.

In his July 30 start against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park, Clemens had a new manner of meltdown after first-base umpire Greg Kosc made a disputed call that went against him. With two outs in the fifth inning, Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner had flipped a Harold Baines grounder to Clemens, who thought he had beaten the runner to the bag. Instead, Kosc ruled that Clemens had missed first base and called Baines safe, which allowed what ended up being the winning run to score for the White Sox. Clemens charged at Kosc to argue the call and made incidental contact with the umpire, which resulted in his automatic ejection. Now he came completely unglued – he claimed to have hyperventilated twice during his rampage – and eventually was carried off the field by teammates Jim Rice and Don Baylor. Clemens was suspended for two games and fined, but his outlook on his punishment was revealing: In his autobiography, he stated, “As it turned out, all I lost was a day’s pay – little more than $1,000 – and $250” [for paying his teammates’ (Bruce Hurst and Al Nipper) minor fines].15 A fine was no great consequence to Clemens and, from this point on, he often alternated feats with fits over the course of his career.

The 1986 Red Sox rolled into the playoffs, with Clemens winning his last seven decisions, but Clemens’ own postseason hopes seemed jeopardized when John Stefero’s line drive hit his pitching elbow in his final regular season start, against Baltimore on October 1. X-rays were negative and the swelling went down in time for Clemens to make his Game One start in the ALCS against the California Angels at Fenway. Clemens made three starts in Boston’s hard-fought seven-game series against the Angels: Game One was forgettable as he surrendered eight runs (seven earned) in 7⅓ innings and Game Four resulted in a no-decision in 8⅓ innings during Boston’s extra-inning loss, but in the clinching Game Seven he dominated the Angels and allowed only one run in seven innings to help send the Red Sox to the World Series for the first time since 1975.

World Series Game Two was a Clemens-versus-Gooden rematch, but neither pitcher lasted longer than five innings; a flu-ridden Clemens gave up four walks and three runs in 4⅓ innings of a game that Boston won 9-3. His second start came in Game Six, with the Red Sox holding a 3-2 edge in games, and he struck out eight while surrendering only two runs (one earned) in seven innings. The Red Sox had a 3-2 lead when Clemens was lifted from the game for a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning, but there was controversy over the timing of his exit. Clemens had torn open a blister and had begun bleeding, and manager John McNamara later claimed that Clemens had asked out of the game as a result, a contention that Clemens and several of his teammates denied. Game Six went down in Red Sox infamy as Calvin Schiraldi combined with Bob Stanley, Bill Buckner, and fate to lose to the Mets 6-5 in 10 innings. The Mets’ 8-5 victory in Game Seven kept Clemens from putting the ultimate jewel in the crown of his 1986 season, a campaign during which he went 24-4 with a league-leading 2.48 ERA and became the first player to win the Cy Young Award, American League MVP Award, and All-Star Game MVP Award in the same season.

In addition to all of his on-field success, Roger and Debbie Clemens welcomed their first son, Koby, into the world on December 4, 1986. In what became a theme, Clemens gave all four of his sons names that begin with the letter “K” – Kory, Kacy, and Kody followed Koby – since it is the baseball scoring abbreviation for a strikeout.

The relationship between Clemens and the Red Sox took a downturn when Clemens walked out in the middle of spring training over a contract dispute. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth eventually negotiated an agreement between the team and its star, but the incident did not bode well for the future. The Red Sox had a miserable 1987 season, finishing at 78-84, though Clemens won his second consecutive Cy Young Award with a 20-9 record, 2.97 ERA, and seven shutouts.

In 1988 Clemens created a minor stir by deciding to pitch against the Angels in Anaheim rather than return to Houston for the birth of his second son, Kory. He earned a complete-game victory in that May 30 game on his way to an 18-12, 2.93, eight-shutout season. The Red Sox rebounded to win the AL East in 1988 but were swept in the ALCS by the Oakland Athletics, though Clemens pitched adequately in his Game Two start.

The biggest firestorm Clemens ignited that year came on December 5 when he gave an interview to a Boston television station in which he attacked anyone and everyone associated with the Red Sox, from management to teammates to fans. His complaint, “Travel, road trips and carrying your own luggage around isn’t all that fun and glory,”16 propagated the stereotype of the spoiled, pampered athlete and cast him in a negative light to fans.

Clemens did play for the Red Sox through the 1996 season, winning his third Cy Young in 1991 and leading the AL in ERA from 1990 to 1992, but he continued to be antagonistic with the media and, in turn, both the media and fans emphasized his shortcomings – real and perceived – more than his accomplishments.

One highly scrutinized event was a tantrum in Game Four of the 1990 ALCS in which the Athletics again swept the Red Sox. Clemens had pitched six shutout innings in Game One, but Boston had lost, and things were not going well at the outset of Game Four. With Oakland leading 1-0 and two outs in the second inning, Clemens began cursing from the mound at home-plate umpire Terry Cooney over balls and strikes and was ejected from the game. When Clemens realized that he had been tossed, he charged Cooney and pushed right-field umpire Jim Evans aside, an offense for which he was fined $10,000 and suspended for the first five games of the 1991 season.

Rather than lie low after such an ignominious end to the season, Clemens gained additional notoriety off the field when he and older brother Randy were arrested at a Houston nightclub on January 18, 1991. Randy had become involved in an altercation, and Roger was arrested for hindering the security guard – an off-duty police officer – who was attempting to arrest his brother. He was found “not guilty” of the charge, but his fame was now increasing for the wrong reasons.

In 1992 Clemens further strained his relationship with the Red Sox when he reported eight days late for spring training; however, he still registered another stellar campaign on the mound, finishing 18-11. After he posted his first losing record in 1993 – 11-14 with a 4.46 ERA – speculation renewed about how much longer Clemens would last. He pitched well in strike-shortened 1994, but in 1995 he had a bloated 4.18 ERA and again came up short in the postseason, though he received no decision in the Red Sox’ ALDS Game One extra-inning loss to the Cleveland Indians.

While Clemens was in an up-and-down phase of his career on the mound and was in the process of alienating Boston fans and management, he was still popular enough with fans nationwide that he made several guest appearances as himself on different television shows. Clemens even showed a sense of humor by taking a role in the animated The Simpsons episode titled “Homer at the Bat.” In the course of the story, Clemens – as himself – is hypnotized into thinking that he is a chicken and spends much of the episode squawking and clucking. His acting exploits also included the big screen, for which his most notable role was as an unnamed flamethrower who pitches to Ty Cobb in the 1994 film Cobb, based on Al Stump’s biography of the Georgia Peach.

In 1996 Clemens posted his second losing record, 10-13, but had a more respectable 3.63 ERA and led the AL with 257 strikeouts. He momentarily turned back the clock 10 years by registering his second career 20-strikeout game, against Detroit at Tiger Stadium on September 18; it was also his 192nd victory, which tied him with Cy Young atop the Red Sox’ all-time list. Nonetheless, Red Sox general manager Dan Duquette considered his 40-39 record for the team from 1993 through 1996 and questioned whether Clemens might be in the “twilight” of his career; he apparently did not see him as a player around whom to rebuild the team into a perennial contender. Clemens spurned Boston’s contract offer and signed for three years and $24.75 million with the Toronto Blue Jays.

Toronto was far removed from its consecutive World Series victories of 1992-1993 and was not a contender during Clemens’ stint with the team, but “Rocket” was not finished yet after all. Quite the contrary, the brief Blue Jays era of 1997-1998 was Clemens at his dominant best as he went a combined 41-13 with a 2.33 ERA and 563 strikeouts, winning the pitching Triple Crown – wins, ERA, strikeouts – in both years as well as his fourth and fifth Cy Young Awards. He also exacted revenge against the Red Sox in his first start as a Blue Jay at Fenway Park on July 12, 1997, when he pitched eight innings of one-run ball and struck out 16 batters.

In time, a cloud of suspicion gathered over this mid-30s pitching renaissance for two reasons: 1) The prevalence of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) in baseball by this time, and 2) the hiring of Brian McNamee as Toronto’s strength and conditioning coach after the 1997 season. Baseball was in the midst of its PED era and – as was the case with most players – no public accusations were made against Clemens at the time; however, McNamee later claimed that he injected Clemens with the steroid Winstrol in 1998.

Clemens longed to pitch for a contender again and his trade request was granted on February 18, 1999, when Toronto traded him to the New York Yankees – an old adversary with whom he had engaged in numerous beanball wars – for starter David Wells, reliever Graeme Lloyd, and second baseman Homer Bush. As a Yankee, Clemens was back in the center of the baseball universe, but that was a mixed blessing as he turned in an inconsistent 14-10, 4.60 campaign.

Clemens longed to pitch for a contender again and his trade request was granted on February 18, 1999, when Toronto traded him to the New York Yankees – an old adversary with whom he had engaged in numerous beanball wars – for starter David Wells, reliever Graeme Lloyd, and second baseman Homer Bush. As a Yankee, Clemens was back in the center of the baseball universe, but that was a mixed blessing as he turned in an inconsistent 14-10, 4.60 campaign.

The 1999 postseason began promisingly as Clemens pitched seven scoreless innings in the ALDS-clinching Game Three against the Texas Rangers, but the ALCS was another matter altogether as Clemens fizzled in his return to Fenway in a Game Three marquee matchup against Boston’s new ace, Pedro Martinez. While Martinez pitched seven shutout innings and struck out 12, Clemens suffered the Yankees’ only loss of the series and was battered for five runs in only two innings. As he left the mound in the bottom of the third, Boston fans taunted him by chanting “Where is Rog-er?” That game became a distant memory for Clemens after he won World Series Game Four against the Atlanta Braves with a 7⅔-inning, one-run performance that capped a Yankees sweep. The one prize, a World Series ring, that had eluded Clemens for his entire career was now his: “Tonight, I know what it’s like to be a Yankee. I am blessed,” he exulted.17

Prior to Game Two of the World Series at Atlanta’s Turner Field, Clemens had been named – along with 29 other players – as a member of the All-Century Team. The 100 nominees for the team had been chosen by a panel of experts and had been presented at that year’s All-Star Game, but it was the fans who had voted for the players. Clemens was the only active pitcher – and one of only four active players – voted onto the team, joining Cal Ripken Jr., Ken Griffey Jr., and Mark McGwire. This accolade and his first World Series championship appeared to validate Clemens’ tunnel-vision tenacity in pursuit of his goals.

On the heels of reaching the pinnacle of professional success, Clemens experienced one of the lowest points in his personal life. In May 2000 his ex-sister-in-law Kathy, who had been married to his brother Randy and had been like a mother to him when he had first moved to Texas, was murdered in a home-invasion robbery in Houston. Kathy’s son Marcus had adopted his father Randy’s drug habit, and the robbery was tied to money and drugs. Roger blamed Randy’s substance-abuse addiction for the couple’s divorce, his nephew’s drug addiction, and Kathy’s murder, and he became alienated from the brother who had exerted such tremendous influence on his life, his outlook on the world, and his early career.

On the mound in 2000, Clemens posted a pedestrian 13-8 record and lost his two starts against Oakland in the ALDS, but he experienced a reversal of fortune from the previous year’s ALCS in Boston in his Game Four start against the Seattle Mariners. In a game as dominant as any he had ever pitched, he set an ALCS record by striking out 15 batters in a one-hit shutout. It was an amazing performance for a 38-year old power pitcher that also served as an endorsement for Clemens’ now-legendary workout regimen – one that players half his age were unwilling to attempt – which again fell under the auspices of Brian McNamee, who had joined the Yankees as an assistant strength coach in 2000.

Clemens turned in another eight shutout innings in World Series Game Two against the crosstown Mets, a Series the Yankees won in five games. The focus of the game, though, was a bizarre incident that occurred in the top of the first inning. Mets catcher Mike Piazza, whom Clemens had hit in the head with a pitch in a regular-season game on July 8, shattered his bat hitting a soft liner that squibbed foul into the Yankees dugout. Clemens picked up the barrel piece of the bat and threw it in Piazza’s direction as he ran up the baseline. The shard almost hit Piazza, who was angered and exchanged words with Clemens as both benches emptied. Clemens was not ejected for his action and dominated the Mets with eight innings of shutout ball in which he allowed only two hits and no walks and struck out nine. After the game, Clemens offered the implausible excuse that he had thought he had the ball, rather than the barrel of Piazza’s bat, which still did not explain why he threw it toward Piazza rather than first baseman Tino Martinez. Nobody believed Clemens, and he was fined $50,000 for the incident.

In 2001, a season in which McNamee has claimed he injected Clemens with the steroids Sustanon 250 and Deca-Durabolin, Clemens raced out to a 12-1 record that garnered him his second career All-Star Game start. He took his record to 19-1 before his first attempt at win number 20 was placed on hold by the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001. After America regrouped, and MLB resumed play on September 17 at the behest of President George W. Bush, Clemens finished the season 20-3 with a 3.51 ERA and earned his sixth Cy Young Award. The Yankees again made it to the World Series, and Clemens registered a 1.35 ERA over 13⅓ innings in two starts against the Arizona Diamondbacks. In Game Three, he scattered three hits in seven innings in a 2-1 win. He engaged in a Game Seven duel against Curt Schilling that the Yankees lost when Luis Gonzalez looped an RBI single off Mariano Rivera to win the game in the bottom of the ninth inning.

Clemens was solid, though no longer spectacular, with the Yankees in 2002-03. He did reach both the 300-win and 4,000-strikeout milestones in a 5-2 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals at Yankee Stadium on June 13, 2003, becoming the first pitcher to hit both landmarks in the same game. He had said repeatedly that he was retiring after the 2003 season, so when he walked off the mound of Miami’s Pro Player Stadium after pitching seven innings of three-run ball in World Series Game Four on October 22, 2003, everyone assumed it was his swan song. There was no fairytale ending to his story, though, as the Yankees fell to the Florida Marlins in six games.

Clemens’ retirement lasted little more than 2½ months. Shortly after Yankees free agent, friend, and fellow Houstonian Andy Pettitte signed to play for the Houston Astros, Clemens joined him and the pair set Houston abuzz with the hope that they could help franchise icons Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio reach the promised land of the World Series before they too reached retirement age.

Although 2004 was his first year in the National League, Clemens registered the same results he had through most of his career: He posted an 18-4 record, 2.98 ERA, and 218 strikeouts for which he won his record-extending seventh Cy Young Award, joining Gaylord Perry, Randy Johnson, and Pedro Martinez as the only pitchers to win the award in both leagues. He also started his third All-Star Game – this time for the NL – in his adopted hometown of Houston, where he had started his first All-Star Game for the AL 18 years earlier.

The Astros were the NL wild-card team in 2004, and Clemens started the franchise toward its first-ever postseason-series victory in 43 seasons of existence by winning NLDS Game One against the Atlanta Braves. Against the St. Louis Cardinals in the NLCS, he won Game Three but lost the decisive Game Seven; however, he received none of the criticism he had often endured in Boston and New York when he had fallen short in the postseason. He could do no wrong in his hometown and was becoming a Texas legend on a par with his boyhood idol Nolan Ryan.

Clemens returned to the Astros in 2005 and added to his increasingly larger-than-life exploits. At the age of 43, he led the majors with a 1.87 ERA and might have won an eighth Cy Young Award had he received more run support to improve his 13-8 record. On September 14, in a decision reminiscent of his choice to pitch on the day of his son Kory’s birth, Clemens defeated the Florida Marlins after his mother, Bess, died that morning. In response to those who questioned his decision, Clemens replied that his mother had made him promise to pitch and that the game was important to the Astros’ playoff hopes. It was clear that he was still as driven to win as he had always been.

The Astros were the NL wild-card entry again in 2005 and faced the Atlanta Braves once more. Clemens lost Game Two, but for Houston fans his status grew to mythological proportions three days later in Game Four. On October 9, after the Astros had exhausted their bullpen by the 15th inning of their marathon contest against the Braves, Clemens came to the rescue and pitched three scoreless innings. He earned the win when Chris Burke ended the game with a solo homer in the bottom of the 18th, and the Astros advanced to the NLCS. As if pitching on short rest were not enough, Clemens had also demonstrated a bit of batting acumen when he laid down a perfect sacrifice bunt in the bottom of the 15th.

In the NLCS, the Astros met another familiar opponent – the Cardinals – whom they defeated in six games to reach their first World Series, with Clemens contributing a victory in Game Three. The magic ran out in the World Series, though, as he exited Game One with a sore hamstring after allowing three runs in only two innings. The Chicago White Sox swept the Astros, and Clemens seemed likely to retire permanently.

Alas, he could not stay away from the game, and he lost much of the goodwill he had engendered in 2005 by appearing willing to sell himself to the highest bidder as he engaged in talks with numerous teams. The so-called “family-friendly” clause that had allowed Clemens to remain home for road trips during which he was not scheduled to pitch – and which he insisted upon to the end of his career – now had some people questioning whether his true motive was team success or money. In the end, he signed with the Astros on May 31 and still posted a 2.30 ERA in 113⅓ innings over 19 starts, but the team failed to make the playoffs.

Clemens played the same “Will he or won’t he pitch?” game at the start of the 2007 season before announcing his return to the New York Yankees from owner George Steinbrenner’s luxury box during the seventh-inning stretch of a Yankees-Mariners game on May 6. He posted a mediocre 6-6, 4.18 line over 99 innings before limping off the Yankee Stadium mound with yet another hamstring injury in the Yankees’ October 7 ALDS game against Cleveland.

Once his career was finally over, the countdown to Clemens’ Hall of Fame induction began. Whether media members and fans liked him or not – and there were plenty of people in both camps – his statistics pointed to him being one of the best pitchers ever to play the game. Even so, the voters who cast ballots for players to gain entry into the National Baseball Hall of Fame are told to take a player’s character into account, and all sorts of skeletons fell out of Clemens’ closet upon the release of the Mitchell Report.

First, there were Brian McNamee’s allegations of steroid use. Clemens vehemently denied McNamee’s accusations and, under the advice and guidance of his lawyer Rusty Hardin, went on the offensive. On January 6, 2008, Clemens filed a defamation suit against McNamee. Though Clemens eventually dropped his suit, McNamee filed his own defamation suit against Clemens in 2008, which dragged on for almost seven years before McNamee received an out-of-court settlement to be paid by Clemens’ insurer – not Clemens himself – in March 2015.

The same day that Clemens filed his lawsuit in Houston, CBS-TV’s investigative news show 60 Minutes aired a Mike Wallace interview of Clemens. In the interview Clemens claimed that McNamee had only injected him with vitamin B12 and the painkiller Lidocaine, an assertion that was dubious to many viewers and which made him the butt of countless pain-in-the-butt jokes.

The next day Clemens and Hardin held a press conference in Houston and played a recording of a recent phone conversation between Clemens and McNamee that was to prove Clemens’ innocence. The tape proved nothing as McNamee sounded both too desperate and too cautious to say anything that might incriminate him. Clemens fielded questions from the media, but grew increasingly aggravated and angry as the conference continued. When asked if he thought McNamee’s allegations would affect his chances at being elected to the Hall of Fame, his retort, “I don’t give a rat’s ass about the Hall of Fame,”18 was another statement no one believed, and he soon stormed out of his own press conference.

On February 13, 2008, Clemens was called to testify before a congressional committee in Washington, where he continued to profess his innocence. Some of his testimony contradicted a sworn statement made by Andy Pettitte, who claimed Clemens had told him that McNamee injected him with human growth hormone (HGH). Clemens responded that Pettitte had “misremembered” [sic] their conversation and that he had told Pettitte it was his wife, Debbie, whom McNamee had injected with HGH. There were enough inconsistencies in Clemens’ testimony that a drawn-out legal process resulted in an August 19, 2010, grand-jury indictment for making false statements to Congress. His first trial, in July 2011, quickly resulted in a mistrial, while his second trial ended with his acquittal on June 18, 2012.

Along with the steroid allegations and their attendant legal troubles, Clemens was also accused of having extramarital affairs with numerous women. The two most notable names were those of the late country singer Mindy McCready and pro golfer John Daly’s ex-wife Paulette. Clemens denied these accusations as well, but McCready and Paulette Daly neither confirmed nor denied them, which gave them implicit affirmation in many people’s minds.

All of this dirty laundry was aired in the media in the immediate aftermath of the Mitchell Report, but two books contributed further to the decline of Clemens’ reputation: Jeff Pearlman’s unauthorized biography The Rocket That Fell to Earth, and New York Daily News’ Sports Investigative Team’s American Icon: The Fall of Roger Clemens and the Rise of Steroids in America’s Pastime. Pearlman’s book portrays Clemens in such a consistently negative light that it is easy to dismiss it as one-sided, but the Daily News team’s research into McNamee’s claims casts serious doubt on Clemens’ assertion of innocence. The facts remain, however, that Roger Clemens never tested positive for PEDs and that he was acquitted of all charges of lying to Congress.

Nonetheless, the repercussions of the allegations have resulted in a lack of support for Clemens’ Hall of Fame candidacy. If he is ultimately enshrined, it is entirely possible that a Veterans Committee will have determined his fate after his initial 10-year period of eligibility has passed. His new road to baseball immortality involves rehabilitation of his former reputation as a hard-working star, which will be an arduous process since everything he does now is greeted with suspicion and cynicism, a circumstance that was in evidence when he pitched two games with the independent Atlantic League’s Sugar Land Skeeters in 2012.

Sugar Land, where Clemens lived when he first moved to Texas, received a national publicity boost during the Skeeters’ inaugural season when Clemens pitched in two games in August and September 2012. His motive for doing so was suspect, however, as he had just been acquitted of lying to Congress in June and needed positive publicity during his first time on the Hall of Fame ballot. Some media members believed that Clemens was attempting a late-season MLB comeback to push back his Hall of Fame eligibility by five years in the hope his legal troubles would blow over and that he would be a first-ballot selectee. Clemens denied such claims, but his comment – “I probably overextended myself a little bit. I wanted to see where I was at”19 – after his August 25 start for the Skeeters was interpreted to mean that he was gauging his comeback status.

By his second start, on September 7, the Skeeters had signed Clemens’ oldest son, Koby, a catcher, and father and son formed the battery against the Long Island Ducks. This time, the 50-year-old Clemens clearly left open the possibility of a major-league comeback attempt when he said, “I would have to get ready. It would be fun. There’s no reason why I couldn’t do it next year.”20 Though he had pitched well in both games – and no doubt enjoyed being the center of attention for his pitching rather than his court appearances – this was unaffiliated minor-league ball and his fastball had topped out at 88 MPH, which was hardly the dominant stuff he had once had in his prime.

In the end, Clemens chose to go out as a hometown hero and a winner after his appearances for the Skeeters rather than to risk going out as a failure in one last major-league stint. As of 2015, he and Debbie reside in Houston, where they work to benefit children through the Roger Clemens Foundation and where he also serves as a special assistant to the Astros’ general manager.

Clemens’ work with the Astros and his induction into the Red Sox Hall of Fame at Fenway Park on August 14, 2014, prior to Boston’s game against the Astros, show that there is still a place for him in baseball. The March 2015 settlement in the McNamee case may eventually allow Clemens to move past constant discussion of the steroid allegations against him, though the court of public opinion is unlikely to change its judgment. Clemens did not attend the McNamee settlement, saying, “I was not present, nor would have I participated in paying one dime. Everyone knows my stance on the subject.”21 The fact that he had been named on only 37.5 percent of the Hall of Fame ballots in January 2015 demonstrated that the Hall of Fame voters have not changed their stance in regard to Clemens either.

Last revised: November 16, 2015

A version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. For more information, click here.

Sources

Baseballhall.org

Baseball-Reference.com

Boston Globe

CBC Sports

Chicago Tribune

Clemens, Roger, with Peter Gammons. Rocket Man (Lexington, Massachusetts: The Stephen Greene Press, 1987).

ESPN.com

Hartford Courant

Houston.astros.mlb.com

Houston Chronicle

Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader

New York Daily News

New York Times

Pearlman, Jeff. The Rocket That Fell to Earth (New York: Harper, 2009).

Riceowls.com

The Sporting News

Sports Illustrated

Sugarlandskeeters.com

Texassports.com

Thompson, Teri, et al. American Icon (New York: Knopf, 2009).

Yankeeography: Pinstripe Legends, “Roger Clemens,” (2011, A&E Home Video), DVD.

Notes

1 Yankeeography: Pinstripe Legends.

2 CBC Sports, “Clemens lambasted by Blue Jays’ Gaston,” http://www.cbc.ca/sports/baseball/clemens-lambasted-by-blue-jays-gaston-1.817361, accessed July 27, 2014.

3 Roger Clemens with Peter Gammons, Rocket Man, 20.

4 Jeff Pearlman, The Rocket That Fell to Earth, 13.

5 Pearlman, 39.

6 Gordon Lakey, “Houston Astros Free Agent Report – William Roger Clemens,” http://scouts.baseballhall.org/report?reportid=01373&playerid=clemero02, accessed April 11, 2015.

7 Larry Monroe, “Chicago White Sox Free Agent Report – Roger Clemens,” http://scouts.baseballhall.org/report?reportid=00948&playerid=clemero02, accessed April 11, 2015.

8 Clemens with Gammons, 33.

9 Mark Story, “22 things you should know about ‘Rocket,’ ” http://web.archive.org/web/20060615043527/http://www.kentucky.com/mld/kentucky/sports/14749611.htm, accessed August 3, 2014.

10 Pearlman, 76.

11 Clemens with Gammons, 52.

12 http://si.com/vault/cover/1986/05/12, accessed April 11, 2015.

13 Clemens with Gammons, 75.

14 Ibid.

15 Clemens with Gammons, 110-111.

16 Pearlman, 132.

17 Jeff Jacobs, “From Ruth To Clemens, Monumental Dynasty,” http://articles.courant.com/1999-10-28/sports/9910280137_1_yankee-stadium-25th-world-series-babe-ruth-s-monument, accessed July 30, 2014.

18 Mike Lupica, “Either Roger Clemens or Brian McNamee will tell lies on the Hill,” http://nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/yankees/roger-clemens-brian-mcnamee-lies-hill-article-1.311566, accessed December 12, 2014.

19 ESPN.com, “Roger Clemens shines in return,” http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/8303548/roger-clemens-impressive-comeback-sugar-land-skeeters, accessed December 15, 2014.

20 Associated Press, “Roger Clemens solid in outing,” http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/8350222/roger-clemens-solid-again-second-outing-sugar-land-skeeters, accessed December 15, 2014.

21 ESPN.com news services, “Defamation suit vs. Clemens settled,” http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/12509911/roger-clemens-brian-mcnamee-reach-settlement-2008-defamation-lawsuit, accessed March 19, 2015.

Full Name

William Roger Clemens

Born

August 4, 1962 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.