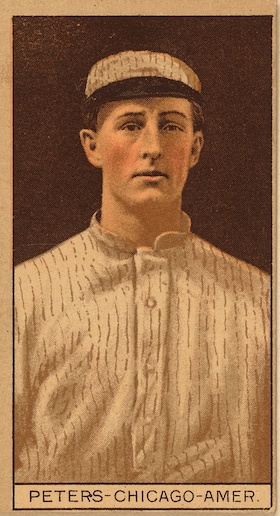

Rube Peters

With Hall of Famers Waddell and Marquard at the top, the roster of major-league pitchers nicknamed Rube contains about 20 entries. Among the least-remembered of these is Rube Peters, a pre-World War I right-hander who had brief tours of duty with the Chicago White Sox and Brooklyn Tip-Tops. Like countless other aspiring hurlers, Peters lacked the talent needed to sustain a big-league career. As a result, he spent most of his adult life working in New Jersey shipyards. But if based only on the experience of two summers, he could still rightfully claim the distinction of having been a major-league ballplayer.

With Hall of Famers Waddell and Marquard at the top, the roster of major-league pitchers nicknamed Rube contains about 20 entries. Among the least-remembered of these is Rube Peters, a pre-World War I right-hander who had brief tours of duty with the Chicago White Sox and Brooklyn Tip-Tops. Like countless other aspiring hurlers, Peters lacked the talent needed to sustain a big-league career. As a result, he spent most of his adult life working in New Jersey shipyards. But if based only on the experience of two summers, he could still rightfully claim the distinction of having been a major-league ballplayer.

Otto Casper Peters was born on March 15, 1885, in Grantfork, Illinois, a tiny (population about 150)1 farming village located in the far south prairielands of the state, about 35 miles from St. Louis. He was the youngest of seven children born to Anton Peters (1837-1909) and his wife, Johanna (nee Kamann, 1841-1931), German Catholic immigrants who settled in Grantfork around 1874.2 Little is known of Otto’s youth except that he left school after the fifth grade,3 presumably to work on the Peters family farm. He also learned the carpentry skills needed to assist his father in building houses and barns in and around the village.

Our subject got a late start in baseball. According to a perhaps apocryphal account of his beginnings by Chicago Tribune sportswriter Sam Weller, 17-year-old Otto Peters and his father saw their first major-league game in May 1903, seated in the left-field bleachers of South Side Park, then the home of the Chicago White Sox. Enthralled, the teenager exclaimed at game’s end: “Dad, some day I’m going to be a baseball pitcher and pitch for Chicago.”4 A skeptical but indulgent Anton Peters did not oppose his son’s ambition, permitting Otto to “secure a baseball and learn a little about the game with other boys around the country [sic].”5 In time, he found a place on a local amateur club as a first baseman. Otto also acquired the knack for throwing a curveball and tried his hand at pitching.6 Good sized (eventually 6-feet-1, 195 pounds) and with a strong arm, he soon became a full-time pitcher.

In 1906, 21-year-old O.C. Peters, as he was then called, began his journey toward the majors by pitching for a semipro team in Pierson, Illinois.7 The following year he hurled for a faster nine, the Madisons of Edwardsville. There, the local press began referring to him as “Rube” Peters.8 The nickname stuck, and Peters would be called Rube for the remainder of his career.9 He entered the professional ranks in 1908, signing with the Dallas Giants of the Class C Texas League. Peters made an immediate impression in the preseason, holding the National League New York Giants to one hit in six innings of exhibition-game hurling.10 He continued strong when the regular season opened, winning 11 of his first 13 Texas League decisions. Rube finished his maiden pro campaign at 24-10, posting the most victories of any pitcher in the circuit.

Rube’s excellent work did not go unnoticed, and in early September he was drafted by the St. Louis Browns.11 On the way home to Grantfork at the end of the Texas League season, he stopped at the Browns’ offices, where club owner Robert Hedges assured Rube that he would receive a thorough tryout in training camp the following spring.12 But soon thereafter, Dallas boss Joe Gardner quietly persuaded Hedges to sell Peters back to his club.13 Meanwhile, Peters arrived home in time to swear out arrest warrants for three Old Ripley residents involved in an incident that left his older brother Joe Peters with a nonfatal gunshot wound to the head.14 Rube spent the rest of the offseason visiting nearby relatives and friends, and trying to keep himself in shape.

Perhaps surprisingly, Peters did not resent being returned to the Texas League, declaring himself “delighted to think that he will be with Dallas another season.”15 But his encore was not the success of his freshman season. Rube’s pitching was inconsistent. He alternated gems, like a no-hitter thrown at Waco on July 28, with a slew of disappointing outings. To a certain extent, the Dallas Morning News attributed the fall-off in performance to a “slight case of malaria” and other unspecified illnesses.16 More ominously, the newspaper later complained that Peters was “not in shape” or out of condition,17 often turn-of-the century sportswriter code for player drinking or other dissipation.18

Whatever the cause, Peters’ 12-12 record was a real comedown from the season before, and cooled major-league interest in him. Thereafter, Rube’s career took a curious turn. In the fall 1909 minor-league player draft, Peters was selected by the Memphis Turtles of the Class A Southern Association. But no sooner had Memphis taken Peters than Turtles manager Charlie Babb publicly declared that he had no use for him, and would return Peters to Dallas if the club wanted him back.19 And when Dallas did not seek Peters’ return, Babb quickly placed him on waivers.20 No takers there, either. In the meantime, Rube spent the winter working as a carpenter in Galveston, where he also found a wife, 23-year-old Bessie (Elizabeth) Parr.

Invited to spring camp, Peters unexpectedly made the Memphis roster. But he pitched erratically once the regular season began, going 4-5 for the Turtles. In mid-June he was sold to the Jackson (Mississippi) Tigers of the lowly Class D Cotton States League.21 At first, he fared no better there. “Rube was flayed alive when he first went to Jackson,” claimed the New Orleans Item. But once he learned the spitball from teammate Harry Peaster, Peters “developed into a bearcat,”22 posting a 15-7 record for the Tigers. Notwithstanding that, the start of the 1911 season found Rube still stuck in Jackson and off to a slow start. With his record standing at a lackluster 10-14, Peters was purchased in mid-July by the Minneapolis Millers of the Class A American Association. His debut for the Millers on July 16 was particularly auspicious. In the opener of a doubleheader, Peters shut out the Milwaukee Brewers, 2-0. He then came back to win the nightcap with several innings of scoreless relief work. From there, Rube never looked back, posting an 11-3 mark for the pennant-winning Millers, and leading American Association hurlers in winning percentage (.786).

In a single season, Rube Peters had gone from toiling in an obscure minor-league venue to hot major-league prospect. In the annual player draft, a number of big-league clubs sought him but, as an adjunct of a complicated National Commission ruling involving the rights to Minneapolis slugger Gavvy Cravath, Peters was awarded to the Chicago White Sox.23 The acquisition of Peters was reported to have “elated” White Sox boss Charles Comiskey,24 while Sox manager Jimmy Callahan was “banking highly on [Peters] to do some good work for the American Leaguers during the coming season.”25 The hype continued during the preseason, but, curiously, Peters was no longer described as a spitballer. Now he was identified as the practitioner of a Christy Mathewson-like fadeaway. But as explained by Rube, his out-pitch was “simply a slowball that breaks in to a right-handed batter and out to a left-hander. It comes over with a spinning motion, so that if the batter does hit it, he seldom hits it squarely on the nose.”26

As the 1912 season started, the White Sox staff was populated by giants, with Ed Walsh, Jim Scott, Joe Benz, George Mogridge, Doc White, and Peters all 6 feet tall or better.27 Of more concern to Peters, competition for pitching assignments would be fierce. Three games into the schedule, Rube got the chance to show his stuff, making his major-league debut against the St. Louis Browns on April 13, 1912. He turned in a route-going three-hitter but lost 2-0, undone by a decisive fourth-inning St. Louis rally that consisted of a walk, two errors, and a wild pitch. Rube was battered by Detroit 10-1 in his next outing, but notched his first big-league victory on April 21, an 8-3 triumph over the Browns.

That win touched off a torrid stretch of outstanding White Sox baseball. By May 28 the club’s first-place record stood at 27-9. From there, however, the campaign headed downhill for both the White Sox and Peters. Injuries to White and Frank Lange, the long illness of Scott, and the overwork-induced fatigue of Walsh required manager Callahan to place more and more of the pitching burden on youngsters like Benz, Mogridge, and Peters.28 And when they proved unequal to the task, Callahan responded with panicky disciplinary measures. In mid-July he docked Benz and Peters $50 each for alleged noncompliance with their manager’s pitching instructions and for defensive shortcomings like failure to cover first base or back up third.29 Shortly thereafter, Peters was placed on the trading block, one of four Chicago players publicly offered to the Minneapolis Millers in exchange for outfielder Otis Clymer.30 Minneapolis declined the deal. A month later and with the finish of an unsatisfying fourth-place (78-76) season in sight, the White Sox optioned Peters to the Sacramento Sacts of the Double-A Pacific Coast League.31

Truth be told, Peters had not been an impressive rookie. His 5-6 win-loss record was facially decent, but his other pitching numbers were not. In 108⅔ innings pitched, Rube had allowed 134 hits. His 39 strikeouts were equaled by his total walks/hit batsmen, and his ERA (4.14) and WHIP (1.537) were well above Deadball Era norms. Nor did he show improvement once in Sacramento: 0-3 in four late-season PCL starts. Despite that, Chicago brass was reported to retain Peters in high esteem. During the offseason, a nationally syndicated column by veteran sportswriter Sam Crane maintained that Peters was slated for the incoming White Sox rotation. Indeed, manager Callahan “has given it out that he thinks Peters will be one of the pitching sensations of 1913,” while club boss Comiskey reiterated that the acquisition of Peters was “one of the best deals I ever made.”32

In fact, Peters held no place in future Chicago plans. When Sacramento turned him back to the White Sox in April 1913, the team immediately sold him to the Omaha Omahogs of the Class A Western League.33 Rube pitched tolerably for Omaha (2.90 ERA in 120⅔ innings pitched),34 but his career soon continued its downward slide. In early August, he was sold to the Spokane (Washington) Indians of the Class B Northwestern League, where he went 3-5 in 12 games for a last-place club.35 Then, as it did for a host of other borderline talents, fortune in the form of the Federal League smiled on Rube Peters.

In February 1914, it was reported that Peters had been signed by the Kansas City franchise of the upstart major league.36 But when the Federals opened spring camp, Rube was in the livery of a league rival, the Brooklyn Tip-Tops. During the regular season he was used sparingly but managed an 11-5 complete-game victory over Baltimore on June 2, the first of his three starts for the Tip-Tops. Next time out, Peters was shelled by Indianapolis, 12-3. The highlight of his campaign came on July 29 when Rube picked up a relief win in an 18-inning, 4-3 victory over St. Louis. In all, Peters appeared in only 11 contests for Brooklyn, going 2-2, with a 3.82 ERA/1.805 WHIP in 37⅔ innings pitched.

The Federal League would continue play as a major league in 1915, but Rube Peters would not be a part of it. Brooklyn released him, bringing his time in the big leagues to conclusion. In all, Peters had appeared in 39 games, going 7-8 with a 4.06 ERA/1.606 WHIP in 146⅓ innings pitched. His 52 strikeouts were exceeded by a total 55 walks/hit batsmen, and opposing hitters had batted a robust .316 against him. Simply put, he had been a marginal major-league pitcher at best. Still, Peters wished to continue playing ball. For the 1915 season, he hooked on with the Fall River (Massachusetts) Spindles of the unclassified Colonial League.37 He won eight of his first 10 starts before the Fall River club disbanded in July. Peters was then transferred to the Brockton (Massachusetts) Pilgrims, where he completed a fine 19-10 season.38

In 1916 Peters took a large step up in competition, signing with the Providence Grays of the Double-A International League.39 He then pitched probably the best ball of his pro career, going 19-10 (1916) and 15-10 (1917) against top-tier minor-league opposition. But his age and lack of previous success likely stifled major-league interest in him. Whatever the reason, Peters received no offers and 1917 proved his last professional campaign. With the country now fully engaged in World War I, Peters abandoned pitching to take a job as a shipyard foreman in Kearny, New Jersey.40 But unlike a host of others seeking defense industry positions, his action was not that of a shirker. At age 33, and with a wife and at least one young child to support,41 Rube was not an apt candidate for military conscription. Rather, he had embarked upon the permanent employment of his post-baseball life.42

By the early 1920s, Peters and family were living in Jersey City. Sometime later that decade, wife Bessie passed away. From then on, Rube shared a residence with his son Harold, a shipyard machinist. Rube retired from shipyard work in 1949 and subsequently relocated to suburban Wayne, New Jersey. In his final years, Peters suffered from the effects of emphysema. On February 7, 1965, he died in Chilton Memorial Hospital in nearby Pompton Plains. Otto Casper “Rube” Peters was 79. After funeral services, his remains were interred in Bay View Cemetery, Jersey City.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail provided herein include the Rube Peters file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Peters family info posted on Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed. 1997).

Notes

1 As per a history of Madison County, Illinois, cited at romeofthewest.com/2011/05/photos-of-saint-gertrude-church-in-grantfork.

2 The Peters children born in Germany were Hendrina (1870-1935), Henry (1871-1936), and Mary (born 1873). Born in Illinois were Joseph (1877-1935), Johanna (born 1880), George (1883-1886), and Otto (1885-1965).

3 As per the 1940 US Census.

4 Sam Weller, “Rube Peters Brings Fadeaway Ball to Aid of White Sox Pitching Staff,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1912.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 As per the Dallas Morning News, April 26, 1908.

8 See, e.g., the Edwardsville (Illinois) Intelligencer, March 13 and 27, and May 18, 1908.

9 The close proximity of Grandfork to Edwardsville (both located in the same county) makes it unlikely that the Edwardsville newspaper would have viewed Peters as a rural bumpkin or other exotic. Rather, his large physical size and the fact that he was a hard-throwing pitcher suggest that the “Rube” nickname was more probably an homage to Rube Waddell. Whatever the case, Peters liked the nickname, preferring it over “Pete,” “Blondy,” and other monikers hung on him, according to a column by syndicated sportswriter Sam Crane published in the Miami Herald, December 10, 1912, and elsewhere.

10 As reported by the Edwardsville Intelligencer, March 27, 1908.

11 As reported in the Dallas Morning News, September 2, 1908, and Sporting Life, September 12, 1908.

12 As reported in the Edwardsville Intelligencer, September 8 and 21, 1908.

13 Gardner had earlier expressed his intention to get Peters and fellow draftee Molly Miller back from St. Louis for the 1909 season. Regarding Peters, Gardner maintained that he was “not fast enough for promotion yet. He has not had sufficient experience. … Another year of seasoning in the minor leagues will fit him for good service in the majors.” Dallas Morning News, September 11, 1908.

14 According to the Edwardsville Intelligencer, October 7, 1908, the shooting was the latest manifestation of a bitter feud between Grantfork and Old Ripley residents that stemmed from unpleasantness at a community picnic six years earlier. Joe Peters survived his injuries and lived another 27 years.

15 As per the Dallas Morning News, January 16, 1909.

16 See, e.g., the Dallas Morning News, June 6 and July 31, 1909.

17 See, e.g., the Dallas Morning News, August 14 and 22, 1909.

18 In fairness to our subject, it should be noted that no evidence of drinking or dissipation was published in 1909. And no complaints about Peters being out of shape or not in condition would be registered in the seasons that followed. But a comment found in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 3, 1910, suggests that Peters might indeed have had a drinking problem: “Rube Peters may never make a Christy Mathewson, but he is following closely in the footsteps of Amos Rusie.” The fireballing Rusie was a conspicuous drinker throughout his Hall of Fame career.

19 As reported in the Houston Chronicle, January 3, 1910.

20 As noted in the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, January 14, 1910, and Sporting Life, January 22, 1910.

21 As reported in the Beaumont (Texas) Enterprise and New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 19, 1910, and elsewhere.

22 New Orleans Item, September 12, 1910.

23 The draft of Peters by the New York Giants was disallowed, and he went to the White Sox as part of the resolution of contested draft claims upon Cravath. For further explanation, see the Denver Post, September 23, 1911, and Sporting Life, September 30, 1911.

24 According to the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, September 27, 1911.

25 Dallas Morning News, February 27, 1912.

26 See again, Weller, Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1912.

27 As noted in a widely syndicated article published the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, June 16, 1912, Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, July 7, 1912, and elsewhere.

28 As later noted in Sporting Life, November 2, 1912.

29 As reported in Sporting Life, July 27, 1912.

30 As reported in the Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, August 11, 1912.

31 As reported in the Salt Lake Telegram and Seattle Times, September 10, 1912.

32 See Sam Crane, “White Sox Have a Real Find in Rube Peters,” Miami Herald, December 10, 1912.

33 As reported by the Riverside (California) Press, April 12, 1913. Omaha reportedly paid $1,000 to acquire Peters.

34 As per the 1914 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 267. The Guide provides no won-lost record for Peters in Omaha. Baseball-Reference has no 1914 stats whatever for Peters.

35 As per the 1914 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 303.

36 As per the Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, Duluth News-Tribune, and Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1914.

37 As reported in the Brockton (Massachusetts) Times, May 20, 1915, and Sporting Life, June 5, 1915.

38 As per Sporting Life, December 11, 1915. Baseball-Reference has no 1915 stats for Peters.

39 As reported in the Boston Globe, March 7, 1916.

40 As reflected in Peters’ WWI draft registration form.

41 The number of children Rube and Bessie Peters raised is uncertain. His newspaper death notice stated that Rube was survived by a son, Harold, and a daughter, Mrs. William (Mildred) Braun. See the Jersey Journal (Jersey City), February 9, 1965. The circa 1970s questionnaire for Rube completed by Harold Peters listed four Peters children: Harold, Joseph, Mary, and Johanna. But the only child whose existence could be confirmed by available government records is son Harold J. Peters (1915-2007).

42 The Providence Grays kept Rube Peters on their reserve list through 1920, but Peters’ final pro season was 1917.

Full Name

Otto Casper Peters

Born

March 15, 1885 at Grantfork, IL (USA)

Died

February 7, 1965 at Pompton Plains, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.