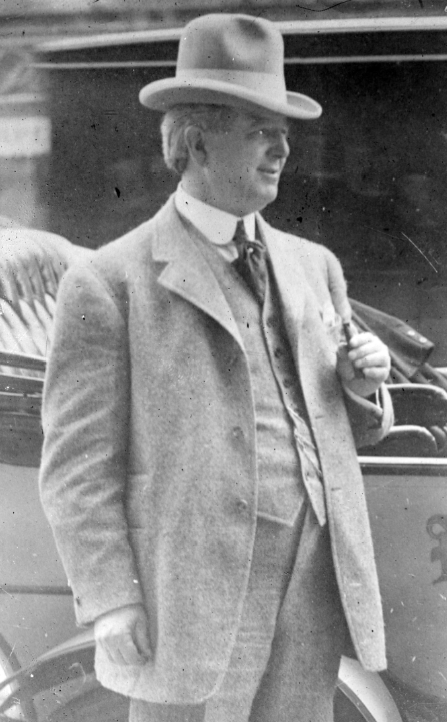

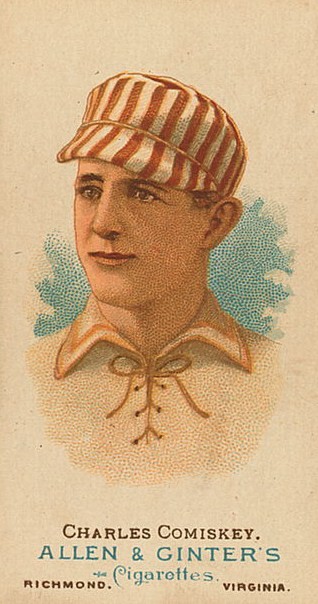

Charles Comiskey

One of the most influential figures in the history of the sport, Charles Comiskey had a 55-year odyssey through professional baseball that ran the gamut: captain of one of the greatest teams of the nineteenth century; league-jumper during the 1890 players’ rebellion; one of the chief architects of the American League’s emergence in 1901 as a major league; longtime owner of one of the league’s most successful franchises, the Chicago White Sox; and a central figure in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal.

One of the most influential figures in the history of the sport, Charles Comiskey had a 55-year odyssey through professional baseball that ran the gamut: captain of one of the greatest teams of the nineteenth century; league-jumper during the 1890 players’ rebellion; one of the chief architects of the American League’s emergence in 1901 as a major league; longtime owner of one of the league’s most successful franchises, the Chicago White Sox; and a central figure in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal.

During his long association with the game, Comiskey was at various points regarded as a labor radical, a visionary executive, and a domineering patriarch who lavished money on his ballpark and the press while at the same time being accused of underpaying his best players. Baseball, Comiskey once wrote, “is the only game that is complicated enough to be always interesting and yet simple enough to be always understood.”1 Ultimately, the same can be said of the Old Roman himself.

Charles Albert Comiskey was born in Chicago on August 15, 1859, at the corner of Union and Maxwell Streets, one of seven children of John Comiskey, an Irish immigrant, and his wife, Mary, a native New Yorker. John served at various times as county board clerk, assistant county treasurer, and representative on the Chicago City Council (including as its first president),2 a résumé that may have given young Charlie valuable experience in the ways of backdoor local politics, which he would later put to use in the halls of the American League’s offices.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

It wasn’t long before Charlie discovered baseball, spending as much time as he could on the old Garden City grounds on the west side of Chicago, enjoying the fledgling game with his neighborhood friends. James T. Hart recalled just before the 1917 World Series how his boyhood pal was already the unspoken leader during their sandlot days in Chicago. He “… seldom went to school more than two months a year,” Hart recalled. “He was the captain of our team. He played all positions, and when any of us were sick, or our parents kept us at home to do the chores, Charlie was ready at a moment’s notice to serve as utility man.”3

Hart also remembered how difficult it was for the team to obtain bats and balls, often using the broken castoffs of older players. “When our team played we would compete on the proposition that the losing team would forfeit a bat. … (W)hen we … were threatened with a loss, Comiskey would start a row with the umpire or the opposing players and break up the game before we lost our bats. He was the foxiest kid in Chicago.”

From Father O’Neill’s Holy Family parochial school, through religious colleges in Chicago and Kansas, Comiskey never let his studies interfere with his principal outdoor recreation. He developed into a fairly skilled hurler, but the elder Comiskey objected to his son’s obsession with baseball, and quickly signed him up as an apprentice to a local plumber. Arguments ensued and in 1876, at the age of 17, Comiskey left home to play third base for an independent team in Milwaukee at $50 per month. His manager, Ted Sullivan, became a scout for Comiskey in later years.4

The following season, Comiskey moved on to pitch for Elgin, Illinois. A right-handed thrower and hitter who stood approximately 6 feet tall, Comiskey included in his repertoire a solid fastball and an assortment of curves. Elgin didn’t lose one of his starts all season, despite facing fairly tough competition from around the Chicago area.5 From there, Comiskey shifted to the Dubuque (Iowa) Red Stockings, where he was reunited with Sullivan. Once again a utilityman, he played first base, second base, and the outfield, and pitched. Possibly more importantly, Sullivan also employed Comiskey as a representative of his successful news agency, where Charlie’s 20 percent commission dwarfed his baseball salary. Comiskey stayed with Sullivan’s Dubuque club for four seasons,6 helping the team win the Northwest League pennant in 1879.

With future Hall of Famer Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn and Laurie Reis on the same pitching staff, Comiskey turned full-time to first base, where, as legend has it, he revolutionized the position. According to most accounts, Comiskey did not “hug the bag,” as was the habit of contemporary first basemen; instead, Charlie positioned himself closer to second, enabling him to cut off grounders hit toward right field.7 He practiced with his pitchers in the morning, making sure they became adept at covering first base whenever he snagged a groundball. Some recent historians have claimed that this approach was already in practice well before Comiskey employed it with Dubuque.8 Even if he was not the first, the story is an early indication of Comiskey’s keen baseball instincts and his penchant for leadership.

The big leagues finally beckoned after an exhibition game in St. Louis in 1882, when Chris von der Ahe, owner of the St. Louis Browns of the new American Association, offered Comiskey a contract. Though Von der Ahe originally suggested that Comiskey not ask for too much money as part of his terms, Charlie found that by his second paycheck his salary was a lot higher than what he had signed for. Comiskey never forgot the gesture, and was said to be one of the old man’s benefactors when Von der Ahe lost his fortune later in life.9

When Von der Ahe and his manager, Comiskey’s old friend Ted Sullivan, had a dispute late in the 1883 season, the Browns owner chose Commy as his new skipper. Charlie responded by piloting his team to four straight American Association pennants, and won the world’s championship in 1886, beating Cap Anson’s Chicago White Stockings of the National League in six games. Although he carried a reputation as an excellent team leader and solid defensive player, Comiskey was not a great hitter. For his career he batted .264 with 28 home runs and 416 stolen bases. Perhaps his best season came in 1887, when he batted .335, scored 139 runs, drove in 103, and stole 117 bases. Far more typical, however, was his showing the previous year, when he batted .254 with 95 runs scored, 76 RBIs, and 41 stolen bases.

In 1890, in a bold move, Comiskey jumped to the Chicago club of the maverick Players League, only to return to the Browns at the end of the season when the PL disbanded and peace was declared. The first baseman’s desertion caused friction between him and Von der Ahe, however, and in 1892 Comiskey signed with the Cincinnati Reds of the National League, where he spent the next three seasons as the club’s manager. Though his annual salary was $7,500, his promised share of the club’s profits never materialized, as there were none to be had.10

Prior to the 1894 season, his last as an active major-league player, the 34-year-old Comiskey was advised by his doctors that he was “threatened with tuberculosis.”11 To aid his health, Comiskey headed for the warmer climes of the South, scouting for new players along the way. Reportedly it was on this trip that Commy hit upon the idea of a new league featuring clubs from the Western states. Upon his return Comiskey contacted Ban Johnson, the sports editor of the Cincinnati Commercial-Tribune, asking if he would be interested in helping to lead this new venture.

Johnson was already embroiled in a feud with Comiskey’s boss, John T. Brush, but Charlie’s well-honed powers of persuasion helped convince Brush to campaign for Johnson to become the first president of the new Western League. The plan worked, and Johnson took control, quickly transforming it into one of the best circuits in the country.

Comiskey, meanwhile, spent the 1894 season with Cincinnati, fulfilling his obligations to Brush. After the season, Comiskey purchased the new league’s Sioux City Cornhuskers and moved the team to St. Paul. There he built his first ballpark, at a cost of $12,000.12 After five seasons in Minnesota as both owner and manager, Comiskey was granted permission by the National League to relocate his franchise to Chicago, on the condition that he could not use the name “Chicago” for his relocated ballclub. Therefore, recalling perhaps his finest moments as a player, Comiskey decided on “White Sox,” honoring the team his Browns had beaten for the 1886 championship.13

Meanwhile, Johnson and Comiskey positioned the Western League to challenge the monopoly of the established NL. In October 1899 it changed its name to the American League. Before the 1901 season, with franchises now placed in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee, the circuit declared major-league status. Quickly gaining credibility with the public, the AL was heralded by The Sporting News as being devoid of the “… cowardly truckling, alien ownership, syndicalism … jealousies, arrogance … mercenary spirit, and disregard of public demands” that the National League had become infamous for.14 Comiskey and Johnson were making a favorable impression with baseball fans, and the NL knew it. The ugly war between the leagues, rife with player-jumping, franchise-shifting, and acrimony on both sides, finally concluded with the establishment of the National Agreement in 1903.

Meanwhile, Johnson and Comiskey positioned the Western League to challenge the monopoly of the established NL. In October 1899 it changed its name to the American League. Before the 1901 season, with franchises now placed in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee, the circuit declared major-league status. Quickly gaining credibility with the public, the AL was heralded by The Sporting News as being devoid of the “… cowardly truckling, alien ownership, syndicalism … jealousies, arrogance … mercenary spirit, and disregard of public demands” that the National League had become infamous for.14 Comiskey and Johnson were making a favorable impression with baseball fans, and the NL knew it. The ugly war between the leagues, rife with player-jumping, franchise-shifting, and acrimony on both sides, finally concluded with the establishment of the National Agreement in 1903.

During the first years of the new century, Comiskey built his club into one of the best in the country. The White Sox captured the 1901 American League pennant behind the strong pitching of manager Clark Griffith and an offense powered by outfielders Fielder Jones and Dummy Hoy. After falling to seventh place in 1903, Comiskey’s White Sox gravitated toward the top of the standings again, with strong finishes in 1904 and 1905 and a second pennant in 1906. Led by pitchers Ed Walsh, Nick Altrock, Doc White, and Frank Owen, and the potent (despite its name) Hitless Wonders offense featuring Frank Isbell, George Davis, and Jones, now the club’s player-manager, the White Sox upset the crosstown Chicago Cubs, winners of a record 116 games, in the 1906 World Series.

Though the team did not win another pennant and World Series title for 11 years, Comiskey built his franchise into one of the most financially successful in the country. At the end of the century’s first decade, the White Sox showed a 10-year profit of $700,000, highest among recorded earnings during that time.15 He turned some of those profits into the World Tour, taken with the New York Giants after the 1913 season.

From the beginning of his tenure, Comiskey established a reputation as an owner passionately involved in the day-to-day affairs of his club. Comiskey was never afraid to express his opinions about the game from his private box. Reporters shared numerous stories of Comiskey railing at his team over bonehead plays or games tossed away. “Sitting next to him at a game, one is likely to be nudged in the ribs, or have his toes stepped on as Comiskey ‘pulls’ on a close play,” stated Baseball Magazine.16

Nor was Comiskey afraid to spend money on his team or his ballpark. By the time of its opening on July 1, 1910, the cost of Comiskey Park and its grounds totaled $750,000, a remarkable amount for the time. Additional seating in subsequent seasons raised the cost to over a million dollars. Commy was also the only owner at this time to own his entire club, the grounds, and all the equipment.17

And though he did everything he could to hold down his players’ salaries, Comiskey spent large sums of money putting together his second great team of the Deadball Era. In December 1914 he purchased second baseman Eddie Collins from the Philadelphia Athletics for a reported $50,000. Less than a year later, he acquired Cleveland Indians slugger Joe Jackson for three players and $31,500.

Throughout his reign, Comiskey polished his reputation as a benevolent monarch. Beginning in 1900, he handed out free grandstand tickets to 75,000 schoolboys each season. He constantly professed love for the fans and when it rained at his ballpark, the occupants of the bleachers were permitted to enter the higher-priced sheltered sections without extra charge. “Those bleacherites made this big new plant possible,” announced Comiskey. “The fellow who can pay only twenty-five cents to see a ball game always will be just as welcome at Comiskey Park as the box seat holder.”18

He later claimed to have given away a quarter of a million tickets to servicemen, and followed that by donating a reported 10 percent of his 1917 home gate receipts to the Red Cross, an amount totaling about $17,000.19 Comiskey regularly allowed the city of Chicago to use his park for special events, often free of charge. The owner’s benevolence also extended to the press, whom he regularly feted with roasts and free drinks.

Comiskey had no qualms when it came to spending money on his ballpark, his city, and his fans. But with his players, those stories are few and far between. Like almost every owner of the time, he held a hard line on player salaries, although recent research has revealed that the White Sox had one of the highest team payrolls in the majors. As historian Bob Hoie has written, the “depiction of Chicago players as woefully underpaid by a tightwad boss” does not stand up to scrutiny.20 Likewise the legend often repeated about Comiskey’s team being known as the “Black Sox” long before the scandal due to their dirty uniforms, a result of their owner’s efforts to cut down on laundry bills; though an amusing anecdote, no evidence has yet been found to confirm that this story is true. Another apocryphal tale has Comiskey benching his star pitcher Eddie Cicotte to keep him from winning his 30th game and collecting on a promised $10,000 bonus. In reality, Cicotte did have a chance to win No. 30 – and clinch the American League pennant – in late September 1919, but he didn’t pitch well and was pulled before the White Sox rallied to win the game.21

During the course of the Deadball Era, Comiskey’s amicable relationship with Ban Johnson disintegrated into open warfare. According to legend, the discord erupted in 1905, when Johnson sent Comiskey a load of fresh fish on the same day that he suspended outfielder Ducky Holmes for an altercation with an umpire the day before. Comiskey, who had already given his extra outfielder, Jimmy Callahan, the day off, was irate. “What does he want me to do?” he bellowed. “Put one of these bass out in the left field?”22 (Versions of this story abound: Some sources say the incident occurred in 1907, and involved Fielder Jones, not Holmes.) A further series of disagreements set the stage for 1919, when two scandals rocked the league and irrevocably split Comiskey and Johnson.

In July 1919 Boston pitcher Carl Mays abandoned the Red Sox and demanded a trade. Johnson ruled that the temperamental pitcher could not be traded until disciplinary action was taken, but Boston owner Harry Frazee ignored the edict and dealt Mays to the Yankees, only to see Johnson suspend Mays. The Yankee owners responded by securing an injunction allowing Mays to play.

League owners immediately took sides: Frazee, Yankee owners Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston, and Comiskey were labeled “The Insurrectionists,” while most of the remaining AL moguls sided with Johnson. Comiskey even pursued a proposal to have his club join the National League; that plan never got off the ground after an uneasy truce between the parties was brokered the following winter.23

By then the Black Sox Scandal hung like a dark cloud over the sport. There is some evidence that Comiskey was aware of the plot to throw the World Series as early as Game One and did nothing to stop it.24 Johnson helped fuel these accusations, while Comiskey threw the burden of the scandal back on Johnson. “I blame Ban Johnson for allowing the Series to continue,” he announced. “If ever a league president blundered in a crisis, Ban did.”25

But Comiskey certainly knew of the fix after the Series ended. One of his players, Joe Jackson, reportedly tried to return his share of the payoff only to be turned away by team executive Harry Grabiner.26 As rumors of the fix spread throughout the sport, Comiskey responded by publicly offering $20,000 to anyone with knowledge of the fix. The announcement was no doubt a public-relations move, intended to make Comiskey appear nobly dedicated to uncovering the truth, no matter the cost. When St. Louis Browns infielder Joe Gedeon did come forward with information, Comiskey rebuffed him and never paid the reward.27

By the end of the 1920 season, details of the plot began to emerge, as several conspirators confessed to their involvement. Even though the eight accused Black Sox were ultimately acquitted of the conspiracy charges filed against them, the scandal devastated Comiskey’s franchise. The eight accused players were banned from the game for life, and after 1920 the White Sox never again finished in the first division during Comiskey’s lifetime.

Charles Comiskey died of heart complications at his lakeside estate in Eagle River, Wisconsin, on October 26, 1931, at the age of 72, and was buried in Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois. He was survived by a son. His wife, Nan Kelly, whom he had married in 1882, preceded him in death in 1922. The Comiskey family continued to control the White Sox until 1959, when they were bought out by a consortium led by Bill Veeck Jr.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 1917.

2 M.L. Ahern, The Political History of Chicago (Chicago: Michael Loftus Ahern, 1886), 145-46.

3 Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1917.

4 David L. Fleitz, The Irish in Baseball: An Early History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009), 43-45.

5 New York Times, October 26, 1931.

6 Hugh C. Weir, “The Real Comiskey,” Baseball Magazine, February 1914. Accessed online at LA84.org.

7 Ibid.

8 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 149.

9 Richard Egenriether, “Chris Von der Ahe: Baseball’s Pioneering Huckster,” The Baseball Research Journal #18 (Kansas City, Missouri: SABR, 1989.)

10 Weir, “The Real Comiskey.”

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Harold and Dorothy Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 309.

15 Harold and Dorothy Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 71.

16 Weir, “The Real Comiskey.”

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 New York Times, October 26, 1931.

20 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox.” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012).

21 Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919.

22 Reading Times, October 27, 1931.

23 Washington Post, December 11, 1919.

24 For a detailed analysis, see Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), 26-60.

25 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total Sports, 2000).

26 Carney, Burying the Black Sox, 69-71.

27 Chicago Tribune, October 27, 1920.

Full Name

Charles Albert Comiskey

Born

August 15, 1859 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

October 26, 1931 at Eagle River, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.