Hugh Nicol

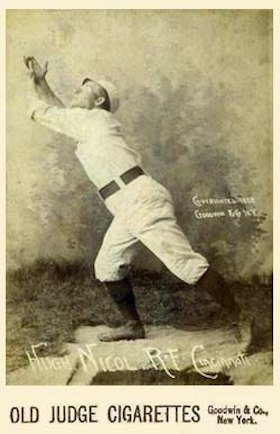

His adoring fans called him “Little Nic.” At 5-feet-4 and 145 pounds, Hugh Nicol was small in stature but large in accomplishments. His showmanship and acrobatic antics on the baseball field reminded observers of circus performers. He was a 19th-century forerunner of Ozzie Smith. His greatest claim to fame was his speed on the basepaths. If Bobby Thomson was called the Flying Scot, Nichol deserves to be called the Supersonic Scot. He set a stolen-base record that may stand as long as the game of baseball is played.

His adoring fans called him “Little Nic.” At 5-feet-4 and 145 pounds, Hugh Nicol was small in stature but large in accomplishments. His showmanship and acrobatic antics on the baseball field reminded observers of circus performers. He was a 19th-century forerunner of Ozzie Smith. His greatest claim to fame was his speed on the basepaths. If Bobby Thomson was called the Flying Scot, Nichol deserves to be called the Supersonic Scot. He set a stolen-base record that may stand as long as the game of baseball is played.

Hugh Nicol was a New Year’s Baby, born on January 1, 1858, at Campsie in Stirlingshire, Scotland. The ninth of the 10 children of Mary MacColgan1 and Robert Nicol, he came to the United States with his parents in 1865. The family settled in Rockford, in northwestern Illinois. The 1870 Census records Robert as a laborer, Mary as keeping house, and no occupation for 23-year-old Eliza. At age 21 son Robert was a carpenter, 16-year-old Edward was a sash and blind maker, and 14-year-old James was working in a cotton mill. At age 12, Hugh was at school, as was his 10-year-old brother, Thomas. The four older children were not in the household at the time of the census.

Hugh must have learned baseball on the streets, backyards, or playgrounds of Rockford. During his teens he played baseball for various amateur clubs in his hometown. It is said that he was also skilled in gymnastics, swimming, rowing, and wrestling.2 He was to use his gymnastic and wrestling skills to augment his income during his career in professional baseball.

In 1879 Nicol started his professional career as a second baseman and outfielder for the Rockford White Stockings in the Northwestern League. He quickly advanced to the major leagues. He made his big-league debut at age 23 on May 3, 1881, for the Chicago White Stockings of the National League. After two seasons in the Windy City, he jumped to the St. Louis Browns of the American Association. During four years in St. Louis, Nicol established himself as a fan favorite, especially among young boys who thrilled to see a person of their own size playing major-league baseball. Nicol was not only a major-league player; he was a star. The boys adopted Little Nic as their hero, cheering every time he stepped to the plate. It was in the field, though, that he earned the most plaudits. He used his great speed to snare flies and line drives that would elude the grasp of most outfielders. According to the St. Louis Globe Democrat, Nicol seemed “very small, but he is quick as a cat and picks up and throws to the infield with great speed.”3 Sporting Life described his play enthusiastically: “He ranks as one of the crack right fielders of the country. He covers a great deal of territory, recovers the ball cleanly and rapidly, and is so accurate and swift a thrower that batsmen who hit into his territory cannot afford to lose time in reaching first base.”4

In each of his first two seasons in St. Louis, Nicol led the American Association in assists by an outfielder. In both 1884 and 1885 he led the circuit in total chances per game by an outfielder. Nicol’s popularity was enhanced by his showmanship. During one spring-training game the Missouri Republican reported that Nicol “tumbled and bounced about, turning summersaults and cart-wheels in a manner that would have done credit to one of Cole’s Arabs [a popular circus act.]”5

Nicol was not a great hitter. He never came close to leading the league in any hitting category. His best major-league batting average was .285 and his top on-base percentage was .341. Perhaps his best day at the plate came at an opportune time, on a September day in 1883 with the Browns chasing the Philadelphia club in the American Association pennant race. In six trips to the plate that day, Nicol “made five corking hits and as many runs. These latter were made by as daring and reckless base running as was ever witnessed. Twice the diminutive player dove face-first into home plate, touching it with his hand just ahead of the ball.”6

Little Nic’s heroics that autumn afternoon helped reduce the Browns’ deficit to 2½ games behind the Phillies. Chris von der Ahe’s boys couldn’t quite catch the Phils, however, and the final standings showed Philadelphia winning the pennant by a one-game margin over second-place St. Louis.

Making five hits in one game was unusual for Nicol, but outstanding baserunning by the Supersonic Scot was par for the course. It is said that he was one of the first players to use the head-first slide.7 His blazing speed and derring-do enabled him to steal 138 bases in 1887, a record that probably will never be broken as long as the current rules of baseball are in force.8 In that same 1887 season Nicol combined with teammate Bid McPhee for the second-highest number of stolen bases by a pair of teammates in a season. Stolen bases were not tabulated before 1885, so it is not known how many bags the speedster pilfered in the early part of his career. He was 29 when he set the record. He stole 103 bases the next year at the age of 30, so it is likely that he swiped a lot of bases in his younger days.

The year 1886 was an eventful one in the life of Hugh Nicol. On April 27 he married May Little in Kansas City. Born in Canada, she was the daughter of Irish immigrants. May and Hugh had three children: Charles (born in Ohio in 1888); Scott (born in Missouri in 1890); and Florence (born in Illinois in 1894). Scott died from injuries suffered while playing football in Lafayette, Indiana, in 1906.

During most of the 1886 baseball season, Nicol was ill with malaria. He appeared in only 67 games for the Browns that year. He recovered well enough to engage in two money-making opportunities during the offseason. In September he was appointed instructor at the Rockford Gymnasium at what The Sporting News called “a good round salary.”9 He told the paper, “I have been suffering with malarial fever more or less all summer. That is the reason I have not been playing my regular position. Recently, however, I have been feeling better and during the past few days I have been working out … with Professor Muegge as my instructor. I have always been a gymnast, but he has taught me many new points which will come in handy when I get to work in my new position at Rockford.”10

Apparently the job as a gymnastics instructor did not consume all of Nicol’s time that fall. The editor of The Sporting News reported receiving a letter from Little Nic, in which he said, “I am getting fame and recognition as a wrestler. … Something funny happened here the other day. Just read about it as it appeared in one of our papers. ‘The little athlete, Hugh Nicol, and General Grant, greatest wrestler of the age, had a bout in the Register office Saturday, and Little Nic did up the General in the first round. … General Grant did not like it and made a jump at the ball player, and had he hit him with the full force offered the athlete would undoubtedly have been killed. But Little Nic was on the alert. He leaped aside and the general was knocked into a thousand pieces. … He was so completely knocked out that the devil had to be called in with broom and shovel and carried out on a scoop.”11

Of course, the wrestler, General Grant, was not knocked into a thousand pieces. However, a plaster bust of General Grant that stood on a wall was shaken off the shelf and crashed to the floor. “When the dust was cleared up the athlete was still in the ring unhurt, while the general lay about him in innumerable fragments. Surely, it was a close call for Nic, the heavy bust being enough to have knocked him into a cocked hat, if it had hit him square on the head.”12

Chris Von der Ahe, owner of the Browns, had become disenchanted with Nicol. The Cincinnati Reds were interested in acquiring the fleet outfielder. Negotiations went on for some time until an agreement was reached in November 1886. The Reds gave Von der Ahe $400 cash plus rookie catcher Jack Boyle. The Browns then released Nicol, and Cincinnati’s new manager, Gus Schmelz, went to Nicol’s home in Rockford and signed Little Nic at a salary of $2,100 for the 1887 season. The Sporting News stated that “Hugh Nicol’s addition to the Cincinnati team means chain-lightning on bases. He is worth all the young blood in Christendom.”13

The assessment of the “Baseball Bible” was on the mark as far as baserunning is concerned. In his very first year in Cincinnati, Nicol set the basestealing record that still stands. One of his Cincinnati teammates, Long John Reilly, at 6-feet-3-inches, was one of the tallest players in the majors; Little Nic was one of the shortest. The two posed together on a baseball card with the caption “The Long and the Short.”

After three good years in the Queen City, Nicol slumped in 1890. He appeared in only 50 games for the Reds before his major-league playing career ended on August 2, at the age of 32. He finished the 1890 season with Kansas City of the American Association. Nicol spent the next 15 years in the minor leagues, as player, manager, or player-manager. In 1891 and 1892 he played second base and outfield for the Rockford Hustlers in the Illinois-Iowa League. In 1892 Little Nic still had some speed left, as in two different games he singled and immediately stole second and third bases.14

Nicol left baseball temporarily in 1893 to manage a cigar store in St. Louis,15 but he was soon back in the game he loved. In 1894 Nicol was player-manager for the St. Joseph Saints of the Western Association. During the next two seasons he played and managed in the Western Association, mainly with the Rockford Forest Citys, but briefly with the Peoria Distillers.

In 1897 Nicol returned to the major leagues as one of the four men who tried unsuccessfully to keep the St. Louis Browns out of the National League basement. He had no more success than the other skippers. The Browns won only eight of 40 games with Nicol at the helm and finished the season with a franchise-record 102 losses. Nicol never played nor managed another game in the big leagues, but his association with the majors was not over. From 1908 to 1912 he served the Cincinnati Reds in another capacity – scout.

Somewhere along the way Nicol had received training as a marble cutter. The 1900 census showed him working for a Rockford monument company as a traveling salesman. In 1901 Nic helped organize the Three-I League, and owned and managed its Rockford club, the Red Sox, for the next three years. He then managed two other clubs in the league. In 1904 he managed the Rock Island Islanders for part of the season. He spent all of 1905 at the helm of the Peoria Distillers.

In 1906 Nicol became the first athletic director at Purdue University, where he expanded physical-education activities and put the athletic program on a money-making basis.16 He also coached Purdue’s baseball team for 10 or 12 years. After resigning from Purdue in 1916 or 1918 (accounts differ), Nicol remained in the area. The 1920 census showed his residence as Lafayette, Indiana, and his occupation as a dealer in stocks and bonds. His health deteriorated and he eventually developed complications from diabetes. He died in Lafayette on June 27, 1921, at the age of 63. He was buried in Grand View Cemetery, near the Purdue University campus, in West Lafayette, Indiana.

Hugh Nicol was a little man, but he was big in achievements. The Sporting News published the following tribute:

A little man with a lion’s heart

Who gamely played an athlete’s part;

Who gave his best wherever placed

And never quit though odds were faced;

Smiling and cheery, alert and quick,

The one and only Little Nic.17

Notes

1 One source gives his mother’s maiden name as McColgain.

2 Ray Schmidt, “Hugh Nicol,” in Frederick Ivor-Campbell, ed., Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 120.

3 St. Louis Globe Democrat, March 18, 1883. Cited by Edward Achorn in The Summer of Beer and Whiskey (New York: Public Affairs, 2013), 62.

4 Sporting Life, cited by Schmidt.

5 Missouri Republican, April 29, 1883. Cited by Achorn, 66.

6 St. Louis Globe Democrat, September 11, 1883. Cited by Achorn, 204.

7 Schmidt.

8 Between 1886 and 1897 stolen bases often were awarded for taking an extra base on a hit by another player.

9 The Sporting News, September 27, 1886.

10 Ibid.

11 The Sporting News, December 31, 1886.

12 Ibid.

13 The Sporting News, November 27, 1886.

14 Schmidt.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 The Sporting News, July 7, 1921.

Full Name

Hugh N. Nicol

Born

January 1, 1858 at Campsie, Stirling (United Kingdom)

Died

June 27, 1921 at Lafayette, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.