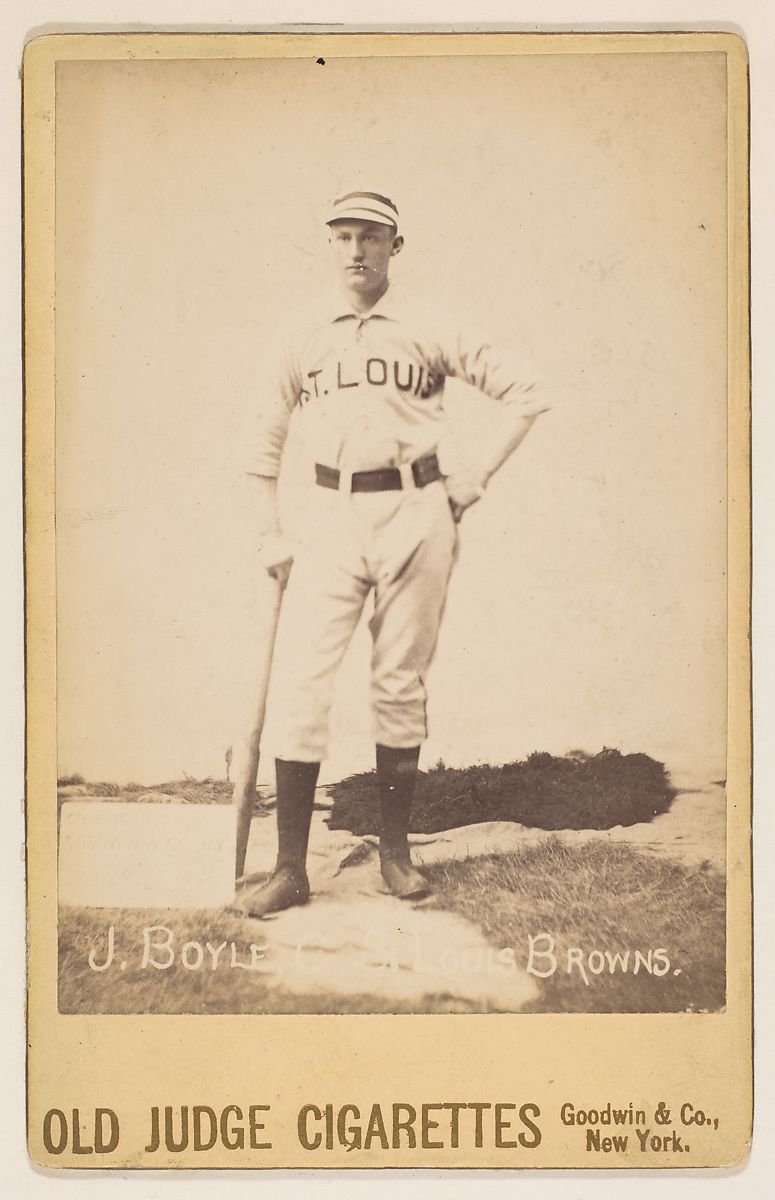

Jack Boyle

“Honest Jack” Boyle was a “19th century multi-position sensation.”1 He was the first of only five major-league players to log 500 games at catcher and at least two seasons of 100 games or more at first base (with Joe Mauer, Joe Torre, Gene Tenace, and Mike Napoli).2 Boyle abandoned boxing to become a major-league catcher in his hometown of Cincinnati in 1886.3 His candid comments on the game of baseball and its players earned him his nickname, reportedly first used in 1892 by his teammates on the Giants to distinguish him from fellow catcher “Dirty Jack” Doyle. His major-league career ended owing to injuries suffered in a knifing in the early morning of December 7, 1898, in Cincinnati.

“Honest Jack” Boyle was a “19th century multi-position sensation.”1 He was the first of only five major-league players to log 500 games at catcher and at least two seasons of 100 games or more at first base (with Joe Mauer, Joe Torre, Gene Tenace, and Mike Napoli).2 Boyle abandoned boxing to become a major-league catcher in his hometown of Cincinnati in 1886.3 His candid comments on the game of baseball and its players earned him his nickname, reportedly first used in 1892 by his teammates on the Giants to distinguish him from fellow catcher “Dirty Jack” Doyle. His major-league career ended owing to injuries suffered in a knifing in the early morning of December 7, 1898, in Cincinnati.

John Anthony Boyle was born on March 22, 18674, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the fourth of seven children of James and Ellen (née Keagan) Boyle, who had immigrated to the United States from southeastern Ireland in the early 1860s. Jack’s younger brother Eddie and nephews Buzz and Jim Boyle also played in the major leagues.

In his teens, Jack worked as a rock cutter and engaged in amateur boxing. As a boxer, he had success in attacking his opponents in a “hammer-and-tongue style,” but wisely “drifted into the baseball business…as he would likely have been a very poor prizefighter.”5

Boyle entered baseball catching for the Blue Lick amateur team in Cincinnati. He left the Blue Licks in mid-season 1886 and joined the professional team in Richmond, Indiana. The Reds picked up Boyle from the Richmond team as it was folding in late 1886, sending him a ticket for the train with directions to report the following day.6 The righty hitter and thrower played in one game for the Reds that year. He had a single in five-at bats while committing three errors and allowing two passed balls.7

At 6-feet-4, Boyle was the tallest man to regularly play catcher during the 19th century.8 (He weighed 190 pounds.) After the season, the Reds traded Boyle and $350 in cash to the St. Louis Browns for the 5-foot-4 Hugh Nicol, in the first trade involving two major-league players.9 The St. Louis press contended that owner Chris Von der Ahe had thrown Nicol away in the deal.10

Upon joining the Browns, Boyle served as the backup to the Browns’ well-respected catcher Doc Bushong. Getting little playing time behind Bushong, and with prospects slim for more, Boyle asked for his release as the Kansas City team was seeking a catcher. The Browns declined his request and instead traded a catcher named Frank Graves.11 When an injury sidelined Bushong in July 1887, Boyle got his chance.12 The St. Louis press moaned that the loss of Bushong at the critical Deadball Era position of catcher would cost the defending champion Browns the pennant. Boyle, however, quickly established himself as the club’s popular “crack catcher.”13 He went on to catch 43 consecutive games, then a major-league record.14 The Browns released Bushong after the season, and he joined the Brooklyn team.

With Boyle as starting catcher, the Browns won the American Association pennant in 1887, repeated in 1888, and finished second in 1889. The St. Louis press credited Boyle’s catching with winning the 1887 pennant for the Browns,15 and the media elsewhere noted the significance of Boyle’s contribution to the Browns’ success in those years.16

Boyle hit only .189 in 1887 as he adjusted to major-league pitching, but then improved to .241 and .245. Despite his lackluster hitting, Boyle developed his penchant for speaking his mind. Talking back to owner Von der Ahe earned him a one-week suspension without pay in 1888, although St. Louis pundits thought it unwarranted.17

A .223 hitter to that point in his career, Boyle’s glove work, his handling of pitchers, and on-field presence kept him in demand. Boyle was viewed as having no superiors at fielding as a catcher.18 The same would later be said for his play at first base for the Phillies, where he was described as the best fielding first baseman the team had ever had.19 His versatility allowed him to play every position on the field (including all three outfield positions) except pitcher. He was deemed capable at all of them.20 In addition to being admired for his conventional fielding, Boyle was credited as the first catcher to employ the (now illegal) stratagem of depositing his mask in the third baseline to discourage runners from sliding home for fear of injury.21

Of Von der Ahe and player-manager Charlie Comiskey, he commented, “Chris Von der Ahe was the best winner and hardest loser I ever saw and Comiskey was a chip off the same block. When we win a game Chris is all smiles, and nothing is too good for the players. When we lose a game all the gang ducks into the clubhouse, change their clothes and get off the lot as soon as possible. … [A]fter a defeat he gets boiling hot, and anybody that crosses him then will get a roasting.”22

Boyle described Comiskey as a great student of the game. He’d forgive an error, but “woe betide the poor ballplayer who has given the game away through some lunk-headed baserunning or other stupid work. He has no mercy on the player who is not alert and watching every point. He will always stick to a brainy sharp-witted player, but he has no use for the drones.”23

Boyle left the Browns to join the Chicago Pirates of the Players League for the 1890 season, along with teammates Comiskey, Silver King, and Tip O’Neill. The Players League formed in response to the National League’s implementation of a reserve clause and the imposition of salary caps on players by both the National League and the American Association. Most of the better professional players made the jump. Boyle played a utility role with the Pirates. He hit .260 for the year, played in 100 games, and split his time between catcher, first base, shortstop, third base, and the outfield. The financially troubled league folded after the 1890 season.

Boyle returned to the Browns for the 1891 season and produced one of his best seasons at the plate, batting .281, with eight triples, five home runs, 18 stolen bases, and 79 RBIs. He primarily played catcher and shortstop but appeared at all the other infield positions and in the outfield.

Boyle caught the wild flamethrowing pitcher Jack Stivetts that year. Honest Jack commented that Stivetts is “just the least bit chicken-hearted and needs ‘jollying’ from his catcher to put forth his best effort.”24 Boyle’s jollying helped the 23-year-old Stivetts to 33 wins in 1891 and to lead the AA in strikeouts with 259, although that was nearly matched by 232 walks.

During the 1891 season, a controversy arose concerning the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League – the team attempted to raid players from the Browns and the Athletics of the American Association. The Pirates targeted Boyle. While idled with an injured hand, Boyle went on a “wild spree” with Browns third baseman Denny Lyons (a fellow member of the “Night Owl Club” with Boyle in Cincinnati and suspended at the time from the team for drunkenness). The invitation came from Pirates pitcher Mark Baldwin,25 who had played with Boyle in 1890 in Chicago.

When Boyle and Lyons then failed to report to the team in Boston on a timely basis, the Browns assumed that Baldwin led a plot to convince Boyle and Lyons to “jump” their contracts and join the Pirates. It wasn’t an unreasonable assumption; a year earlier, Chris Von der Ahe had had Baldwin arrested and locked up in St. Louis for attempting to get Silver King and Comiskey to jump. Baldwin in turn sued Von der Ahe for false imprisonment. Baldwin eventually had Von der Ahe arrested in Pittsburgh some years later as their dispute continued.26

Von der Ahe dispatched a detective to retrieve Boyle and Lyons. The three caught up with the team in Boston on July 9.27 Von der Ahe promptly met with the two and levied heavy fines. Both were penitent and denied any intent to jump their contracts.28 Von der Ahe chalked it up to drunkenness on the part of Lyons, noting that he had stayed relatively sober so far that year. As for Boyle, the owner cited rank ingratitude in view of the $3,000 he was paying the player that season.29

While perhaps not one to jump a contract, Boyle could be tough to sign.30 Following the 1891 season, a free-for-all broke out among the major-league teams as they sought to re-sign players or adjust their rosters following the folding of the American Association and the enlargement of the National League from eight to 12 teams. Boyle took full advantage of the situation, and reportedly had 11 offers. The Browns, who moved to the NL, expected to re-sign Comiskey, Boyle, Tip O’Neill, and Shorty Fuller.31 But Von der Ahe, reported to be hot to sign Boyle,32 was not willing to give a raise to any of his current players. As a result, he lost Comiskey and O’Neill to the Reds, Lyons and Fuller to the Giants, and Stivetts to the Boston Beaneaters.33

Most pundits expected Boyle to sign with his hometown Reds, especially with his friend Charlie Comiskey, who had joined the Reds on a three-year contract,34 recruiting him.35 To prevent the rest of the league from continuing to bid on Boyle and raise his price, the Reds wired the other teams that they wanted Boyle and believed they had him.36 The Reds assumed they had blocked all avenues of escape for Boyle to other teams.37 The St. Louis press criticized the Reds’ efforts, noting, “About the most brazen exhibition of gall witnessed for some time is the Cincinnati Club’s claim to Jack Boyle’s services. Here the club is without a scrap of paper to show Boyle has signed with them and yet have forced other league clubs to keep hands off. This is practically reservation, and if Boyle submits to be reserved by a club who has no claim on him, he deserves what he gets.”38

Boyle turned down an initial offer from the Giants39 and one from the Pirates (with Mark Baldwin again involved).40 He seemed committed to joining the Reds.41 Nonetheless, he remained hesitant to ink a Cincinnati contract if significantly more money might be forthcoming.42 As the Giants continued their pursuit, the Cincinnati press, echoing Reds management, observed, “What makes this case all the more aggravating is the fact that Boyle was allotted to the Cincinnati team by the other League clubs … and that Cincinnati should be allowed to sign him without competition.”43 The Giants’ continued interest related in part to Boyle’s established ability to catch the “puzzling” curveballs of their star pitcher Silver King.44 Eventually, Buck Ewing of the Giants (a former Red) met with Boyle. The two agreed on a contract for $5,500 for the 1892 season with $2,000 paid in advance.45

Much hard feeling arose in Cincinnati over the situation. The press and fans felt betrayed by Boyle, who failed to follow through on his promise to join the team, and by the “Jesse James tactics” of the duplicitous Giants.46 The opinion in St. Louis was that “the Cincinnati club has been guilty of so many disreputable acts that it is really a pleasure to read of her being the victim of a game at which she is most proficient.”47 Boyle explained, “I know that a ball-player’s days are numbered, and I am out to make all I can out of it while I last.”48 He always maintained that he had merely expressed a preference for playing in Cincinnati, and had not made a formal commitment or signed a contract.49

The negotiations concluded, Boyle followed up with the worst year of his career at the plate in New York since his rookie season. He batted .183 with an OBP of .252 and knocked in only 32 runs in 476 plate appearances. Boyle and King were an effective battery in New York, but the press bemoaned the wild “cyclone” pitching of several other Giant hurlers as putting too much burden on Boyle’s fine catching.50 He finished the season leading the league in both errors by a catcher and passed balls.

Regardless of his statistically dreadful performance, the Giants stuck with Boyle. When offered a trade by the Reds for King and Boyle in mid-season, the Giants were willing to trade King but would not let Boyle go.51 The New York press did not view his poor performance as entirely his fault, noting, “Even Jack Boyle, one of the finest players in the country, felt the distressing effect of being a Giant and played poorly.”52 After the conclusion of the 1892 season, Boyle was dealt to the Phillies as part of the trade to bring Roger Connor to New York. The press noted, “There will be considerable regret over the loss of Jack Boyle, who was a conscientious and popular player.”53

Late in the season, Boyle umpired two Giants games against the Baltimore team – perhaps because of his reputation for honesty, perhaps burnishing it. He had also umpired a game in the AA in 1888 and later did so for two in the NL in 1897.

While his play in New York was not much to write about, an off-the-field adventure of Boyle and Silver King received extensive coverage in Boyle’s hometown. As reported in “Base-Ball Gossip” in the Cincinnati Enquirer in mid-May, Boyle and Silver King became mixed up in an “unsavory mess” with two young women from Covington, Kentucky.54

After a game in Cincinnati, Boyle and King invited the women (and perhaps paid their way) to travel unaccompanied (evidently on the train used by the team) to New York to spend some time with the two there. The Cincinnati press headlined that the two attractive young women had eloped with the “Giants’ Mashes.” One of them, Rose Sandman, was linked with Boyle. The report prompted a telegram to Boyle from his mother asking if it was true.55 Boyle (age 26) denied in the press that he had eloped or had any intention of getting married to Ms. Sandman (then age 20).56 Sandman’s mother reported that Jack had called on her daughter several times before the trip to New York.57

The whole situation was considered quite scandalous in Cincinnati, though it got no ink in New York. As it turned out, Boyle surprised his friends and teammates of the time in late December 1894 by announcing that he was heading to Kentucky to marry Sandman.58 Jack and Rose stayed together for the rest of their lives and had two children, James and John, who became well known in the theatrical world as singers and impersonators.59

After his trade to the Phillies, Boyle held out on signing a contract, along with 12 other teammates, until nearly the beginning of the 1893 season.60 Upon joining the team, Boyle proceeded to have two of his best offensive seasons. He hit .286 in 1893, with 29 doubles, nine triples, and four home runs, and drove in 81. He followed up by batting .300 in 1894, with 23 doubles, 10 triples, four homers, and 89 RBIs. He spent those years splitting his time between catcher and first base, as he would for the rest of his career.

Popular with fans and his teammates and respected for his on-field acumen, Boyle was selected by the Phillies for the 1894 season as their captain (a prominent position in the Deadball Era) over three future Hall of Fame teammates.61 Boyle’s role expanded in 1895; he was given charge of the team’s coaching and on-field activities, while manager Arthur Irwin focused on team business matters.62 Billy Nash, the third baseman newly acquired from the Boston Beaneaters, replaced Boyle as captain at the beginning of the 1896 season.63 The team reinstated Boyle as captain in mid-season, either in response to the Phillies’ poor performance or at the insistence of a group of players.64

Boyle’s offensive production declined in 1895, although his fielding at both catcher and first base continued to earn rave reviews.65 During the 1896 season, Boyle hit .297 but his playing time was significantly reduced. As the season wound down, he thrilled fans with a ninth-inning home run to lead the Phillies to victory over the Pirates.66

Boyle played 75 games in 1897 and hit .253. In 1898 he was set to captain the Phillies again,67 but a bout of either malaria or typhoid fever, which required hospitalization, idled him for most of the season.68 He played only six games. In midseason, the Giants negotiated with the Phillies for Boyle’s release, paying a waiver fee of $1,000 in July, but returned Boyle to Philadelphia in August. He was released by the Phillies shortly thereafter.69

Toward the end of that season, Boyle opined that teammate and future Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie – then just 24 and in his third year in the majors – was “the greatest natural ballplayer ever to wear spikes.”70 Although Lajoie had many great years ahead of him, Boyle’s major-league career effectively ended a few months later when he was severely injured in the early morning of December 7 as he walked home from Turner Hall in Cincinnati.

Mystery surrounds the incident – Boyle downplayed it – but apparently an unidentified assailant attacked him from behind with a knife. Boyle suffered three serious stab wounds, a broken arm, and sprained left shoulder.71 He attempted to rejoin the Phillies for the 1899 season, but trouble with rehabilitating his shoulder led him to have it re-examined. This revealed that the broken blade of the knife used in the attack was still embedded in his shoulder.72

His major-league career ended; Boyle continued his involvement in the game for a few years. He played briefly for the Kansas City minor-league team in 1899, for the Toledo team in 1905, and as player-manager for the Terre Haute team in 1906. He umpired in the Eastern League in 1910.73 It appears that he was not one to take guff.74 By the end of the year he was viewed as an outstanding umpire.75 There was speculation that he would move on to umpire in the NL, but health concerns appear to have kept him from continuing.76

Following the end of his baseball career, Boyle operated a saloon at the southeast corner of 7th and Central in Cincinnati. It was officially named Jack Boyle’s Café but usually referred to as Jack Boyle’s poolroom.

Boyle continued to share his thoughts on baseball. In 1910, speaking with Chicago sportswriter William A. Phelon, he identified future Hall of Fame teammate Ed Delahanty and opposing player Pete Browning as the two greatest hitters of his day. He further noted, “‘Del’ cared about how much money he was making, and Pete cared about his statistics, but neither cared much about how the team did. When it came to bunting, Del wouldn’t simply try, and Pete, with much groaning and protestation, could be coaxed into trying but his attempts were fizzles.”77

Boyle’s health began to decline after 1910. He suffered from Bright’s Disease (nephritis), a common cause of death at the time, and still difficult to treat today. Boyle passed away on January 6, 1913, at the age of 45 – “Called Out by the Supreme Umpire,” as headlined by the Cincinnati Enquirer.78 Newspapers from Boston to San Francisco carried the obituary of the famous catcher. He is buried in St. Joseph’s New Cemetery in Cincinnati.

POSTSCRIPT

Twenty-five years after announcing the ballplayer’s passing, the Cincinnati Enquirer received a letter from Phillies fan Everett Mills. Mills asked whether the paper could put him in contact with Boyle. On being advised by the paper that Boyle had passed away many years before, Mills sent a follow up letter. In explaining his inquiry, Mills noted that, when he was a boy in

Philadelphia and without means to pay his way into the ballpark, Jack Boyle often took him in to see the game. Mills went on to write, “The purpose of my inquiry was to learn, first, if he was living and something about his circumstances, and in the event he was needy to assist him in one way or another. When I was young Boyle was more than kind to me and made it possible

for me to get an inside on National league baseball.”

“I probably have seen every ball club, both National and American League, that came to Philadelphia in the last 49 years, and it was during that early period when I had not the price of admission that Boyle helped me. Since it has been only in later years that I have come into leisure, I have been trying to locate him for the purpose stated above, and I regret the news

came to me after his demise.” 79

Last revised: November 13, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to the sources included in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball Almanac.com, TheDeadballEra.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Jayson Stark, “Mauer Playing First–No Catch,” ESPN.com, March 6, 2014 (https://www.espn.com/blog/jayson-stark/post/_/id/652/mauer-playing-first-no-catch/), accessed September 5, 2022.

2 Stark, “Mauer Playing First–No Catch,” Boyle is the only one of the five to have also played shortstop.

3 “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 2, 1890: 16.

4 Most websites list his birthdate as March 22, 1866; however, his death certificate lists March 22, 1867, which is consistent with the census information his parents provided 1870 and 1880.

5 “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 2, 1890: 16.

6 “The Richmond Club Stranded,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 6, 1886: 2.

7 “Base-Ball Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1889: 13.

8 Heffron & Heffron, The Local Boys-Hometown Players for the Cincinnati Reds, (Birmingham, AL: Clerisy Press, 2014) 40.

9 John Marsh, “On the Genealogy of Trades, Part I,” Fangraphs.com, June 25, 2015 (https://tht.fangraphs.com/on-the-genealogy-of-trades-part-i), accessed September 5, 2022. Some reports say the cash amount was $400.

10 “Nicol Signed by Cincinnati,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 17, 1886: 4.

11 “Sporting,” St. Louis-Globe Democrat, December 25, 1887: 11.

12 “No New Catcher-Bushong Will be All Right in Three Weeks or Sooner,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 8, 1887: 8.

13 “The Crack Catcher-Sketch of Jack Boyle, The Now Famous Backstop,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 6, 1887: 9.

14 “Weyhing’s Great Game,”, Cincinnati Enquirer, August 21, 1887: 10. The previous record was 37 games. “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 13, 1887: 7. Boyle’s obituaries variously report his record as being 85 to 87 consecutive games in 1887, but this is not accurate. He caught a total of 86 games that season and played right field after appearing in his 43rd straight game.

15 “Jack Boyle Laid Off,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 5, 1888: 8.

16 “Caught Off the Bat,” Philadelphia Times, July 15, 1893: 8.

17 “Jack Boyle Suspended,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 5, 1888: 4; “Jack Boyle Laid Off,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 5, 1888: 8.

18 “Bushong’s Release,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 25, 1889: 5; “Caught Off the Bat,” Philadelphia Times, July 15, 1893: 8; “The Man Behind the Plate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1896: 8.

19 “The Phillies are All Right with Jack Boyle on First,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 13, 1894: 24; “The Man Behind the Plate,” June 28, 1896: 9.

20 “The Man Behind the Plate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 12, 1897: 4; “The Arena of Sport,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 8, 1891: 24. He pitched in an exhibition game. “Young Jack Boyle Tries His Hand at Pitching,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 1887: 1.

21 “A Catchers’ Row-Baldwin and Robinson Mash Up Masks,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 9, 1889: 2.

22 “Jack Boyle’s Opinion of President Von der Ahe and Comiskey,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 27, 1889: 2.

23 “Jack Boyle’s Opinion of President Von der Ahe and Comiskey.”

24 Getting Ready to Open the Season,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 27, 1892 :18

25 “They Went on a Howling Spree,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 9, 1891: 9.

26 See Baldwin’s SABR Biography for a complete discussion of the affair.

27 “Lyons Remains Loyal,” Boston Globe, July 9, 1891: 4.

28 “Jack Boyle and Denny Lyons Were Drunk but Did Not Jump Their Contracts,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 9, 1891: 8.

29 “Boyle and Lyons Will Join the Browns Today,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 9, 1891: 9.

30 “Fight Will Be Made,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 16, 1891: 1. The Browns had trouble coming to terms with Boyle for the 1891 season.

31 “A Good Team Assured for Next Year in St. Louis,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 22, 1891: 9.

32 “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, November 5, 1891: 6.

33 “Reason Why Some of Vondy’s Stars Refused to Remain with Him,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, November 26, 1891: 8.

34 “Reason Why Some of Vondy’s Stars Refused to Remain with Him.” Comiskey signed for $7,500 per year for three years with the Reds.

35 “Comiskey’s Cincinnati Team,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 7, 1891: 8; “Boyle and Fuller Meet Him at Grand Hotel,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 9, 1891: 2.

36 “The Cincinnati League Club Having Trouble Signing Catcher Jack Boyle,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 21, 1891: 8

37 “Von der Ahe’s Views-The Great Association Chief Talks Good Horse Sense,” The Sporting Life, December 5, 1891: 1.

38 “Base-Ball Gossip,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 4, 1891: 9.

39 “Boyle Sticks-He Prefers to Play Here and Declines New York’s Offers,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 13, 1891: 2.

40 “Let Him Alone—Too Much Tampering with Jack Boyle,” Cincinnati Post, November 30, 1891: 2. Baldwin claimed he could have signed Boyle early in the process for $3,500. “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, November 25, 1891: 6.

41 “Boyle to Become a Red To-Day,” Pittsburgh Post, November 26, 1891: 6.

42 “The Cincinnati League Club Having Trouble Signing Catcher Jack Boyle,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 21, 1891: 8; “Lined Up-The Cincinnati Reds for 1892-Nearly All the Players Are Now Said to Be Signed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 20, 1891: 2.

43 “Base-Ball—Boyle May Jump Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 19, 1891: 2.

44 “New Faces in the Big League,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 7, 1892: 2. Boyle had caught King on the Chicago Pirates.

45 “Base-Ball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 21, 1891: 8; “Base-Ball—Boyle May Jump Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 19, 1891: 2

46 “Something More About the Boyle Matter,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 6, 1891: 10.

47 “Baseball Gossip,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 23, 1891: 7.

48 “Let Him Alone—Too Much Tampering with Jack Boyle,” Cincinnati Post, November 30, 1891: 2.

49 “Let Him Alone—Too Much Tampering with Jack Boyle.

50 “Work of the Team in the West-Yesterday’s Games,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 2, 1892: 1.

51 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 13, 1892: 2.

52 “Gossip of the Ring and Field,” (New York) Evening World, June 24, 1982: 5.

53 “Roger Connor Goes Back to New York,” St. Louis Globe-Dispatch, March 12, 1893: 10.

54 “Giants-Mashes-Two of the Giants in Trouble, Jack Boyle and Silver King Have a Time,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1892: 2.

55 “Jack Boyle Does Some More Talking,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 19, 1892: 2.

56 “Nothing to It-Jack Boyle and Silver King Deny Elopement Story,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 18, 1892: 2.

57 “Jack Knew Her-Mrs. Sandman Said Giants’ Catcher Called on Her Daughter Several Times,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 20, 1892: 2.

58 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 13, 1894: 2.

59 “Home on Sad Mission,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 21, 1912: 12.

60 “When Will the Phillies Play Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 15, 1893: 3.

61 Boyle is first mentioned as the captain of the Phillies in July 1894 shortly before he helped save an opposing player in danger of injury in a riot at a ballgame in Philadelphia. “Disgraceful Riot on Ballfield,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1894: 1.

62 “Jack Boyle In Charge,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 10, 1895: 4.

63 “Both Philadelphia and Boston Satisfied with the Nash-Hamilton Trade,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 17, 1895: 11. Nash had captained the Beaneaters in 1895.

64 “And There Were Others,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 22, 1896: 5.

65 See, e.g., “The Man Behind the Plate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 28, 1896: 9, and September 6, 1896: 8.

66 “All Hats Off to Captain Jack Boyle-The Star Performer in One of the Grandest Finishes of the Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 5, 1896: 5.

67 “Boyle May Be Captain, Philadelphia Times, March 27, 1898: 12

68 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 30, 1898: 4. “Gossip of the Game,” Courier-Journal, July 14, 1898: 6.

69 “Phillies Have No Claim for Compensation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1898: 4.

70 “All Sorts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 2, 1898: 31.

71 Jack Boyle’s Injuries More Serious Than Supposed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 9, 1898: 3; “Jack Boyle Assaulted,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 8, 1898: 4.

72 “Knife Blade in Boyle’s Shoulder,” Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1898: 4.

73 “Jack Boyle Will Umpire in Eastern League,” Buffalo News, January 10, 1910: 10.

74 “Players Galore Chased to Clubhouse by Umpire Boyle,” Buffalo Courier, August 5, 1910: 8.

75 “Says Jack Boyle is Star Umpire,” Buffalo Enquirer, January 20, 1911: 8.

76 “Local Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 11, 1911: 11.

77 “Browning & Delahanty,” Baseball History Daily, June 25, 2013 (https://www.baseballhistorydaily.com/2013/06/25/browing-delahanty), accessed October 14, 2022. Originally published in the Chicago Tribune on an unknown date in 1910.

78 “Called Out—By the Supreme Umpire—Jack Boyle, Veteran Catcher of St. Louis Browns, Died After a Long Illness,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 7, 1913: 6.

79 “This Man Did Not Forget”, Cincinnati Enquirer, July 10, 1938, 27.

Full Name

John Anthony Boyle

Born

March 22, 1866 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

January 6, 1913 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.